Despite getting all of their shots, up to half of teens and young adults born with HIV before the virus first became treatable in the mid-1990s may not be protected against diseases like measles, mumps, and rubella.

The nearly 4,500 young adults in the U.S. alone reflect a population previously thought to be safely immunized. But according to a new study, most of them have not received the protection their vaccines were supposed to have provided.

"This has been a number that's been very hard to pin down," George Siberry, a medical officer at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and lead author of the new study, told BuzzFeed News. "What surprised us was how many of these kids with HIV actually are not protected at all."

Unlike this group, HIV-positive babies who are vaccinated after being put on antiretroviral treatments have high levels of protection.

The results highlight the urgent need for doctors to check the medical records of kids born with HIV to see whether their vaccinations were given before or after they were put on effective antiretroviral treatments.

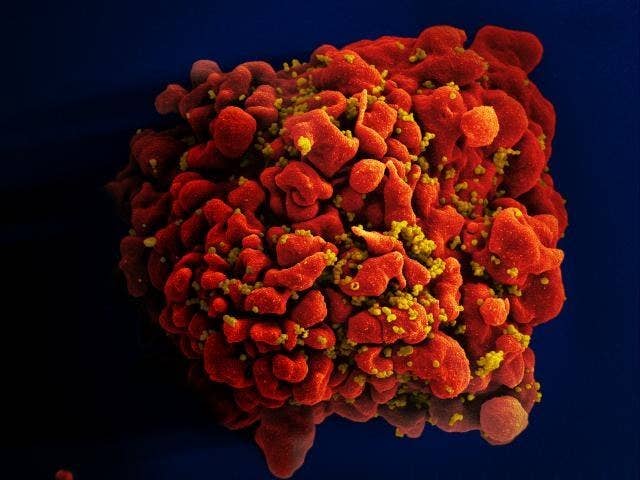

With HIV battling their immune systems, the vaccines couldn't work.

Because these kids were born before the widespread use of antiretroviral therapies, they were vaccinated while the HIV virus was still alive and well in their bodies.

"For a vaccine to work, the body has to be able to make the proper immune response," Siberry said. Since HIV impairs many of the body's immune functions, it not only makes it harder for you to fight infections, it also affects how you then respond to vaccines.

Siberry's study looked at a group of 428 young adults born between 1992 and 2000, and looked at their rates of protection against measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR). Compared with healthy teens, 95% of whom were protected against measles, only 57% of the HIV-infected teens were successfully immunized against measles, the study found. Similar numbers applied for mumps and rubella.

But the results broke down even more clearly once the researchers looked at the years in which kids got immunized. HIV-positive teens who had gotten either one or two of their MMR shots after beginning antiretroviral treatment were more likely to be protected against the diseases.

"The fact that measles is still causing problems in the U.S., and the fact that it's so contagious, made us want to focus on MMR," Siberry said, noting that pockets of unvaccinated children are part of the reason why measles cases have reached a 20-year high.

But the results are likely not just limited to measles, mumps, and rubella. "It will probably apply to many other vaccines," Siberry said.

The problem will be more serious in Africa, where the vast majority of kids born with HIV live.

These days, most of the 100 to 200 children born with HIV in the U.S. every year are quickly put on antiretroviral drugs. Then they're vaccinated.

The problem is much bigger in Africa, where 90% of the estimated 3.2 million children living with HIV live. Less than 24% of these kids are on antiretroviral treatments.

"Starting treatment as early as possible is absolutely critical to very basic short-term survival, especially in Africa where rates of HIV infection in children are still very high — 600 babies are infected with HIV every single day," Stephen Lee, vice president of program implementation and country management at the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation, told BuzzFeed News via email.

The problem is made even worse because, unlike in the U.S., measles is still common in many parts of the continent. Measles is highly contagious and can cause rashes, diarrhea, pneumonia, and even death.