New York City, which has one of the country's highest rates of new HIV infections, has been quietly cutting many of the prevention services needed to fight the epidemic, according to many AIDS advocates.

Over the past five years, the city's Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) has cut hundreds of thousands of HIV tests, closed several free STD clinics, and witnessed a significant rise in STDs such as syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia, according to a report released to BuzzFeed News by two AIDS activist organizations, ACT UP and the Treatment Action Group. Visits to city-run STD clinics have also dropped by roughly one-third — a loss of 40,000 per year.

The city has been making these changes discreetly, the report alleges, "unbeknownst to activists, community members, and contrary to much public rhetoric."

City officials confirmed that services have been cut back. According to Demetre Daskalakis, the city's assistant health commissioner in charge of the Bureau of HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control, the major reason is money: The city's budget for disease control has dropped 38% since 2008.

"Were there funding cuts in New York that have caused significant decreases in services at the STD clinics? Yes. Do we need to fix them? Yes. Are we working as a department to fix them? Yes," said Daskalakis, who took charge of the city's HIV program last year.

But Daskalakis also said that the drop in city-funded testing does not necessarily mean that people aren't getting tested elsewhere, as more individuals seek testing through private insurance or Obamacare.

"New Yorkers are getting tested for HIV, but because New York state is a wonderland of coverage, a lot of that is happening through health care," Daskalakis said. But there are no hard numbers showing how many people are getting tested elsewhere.

HIV testing is the first step in getting high-risk individuals into the health care system and preventing the disease from spreading — particularly when combined with condoms and HIV prevention drugs such as Truvada, often available at STD clinics.

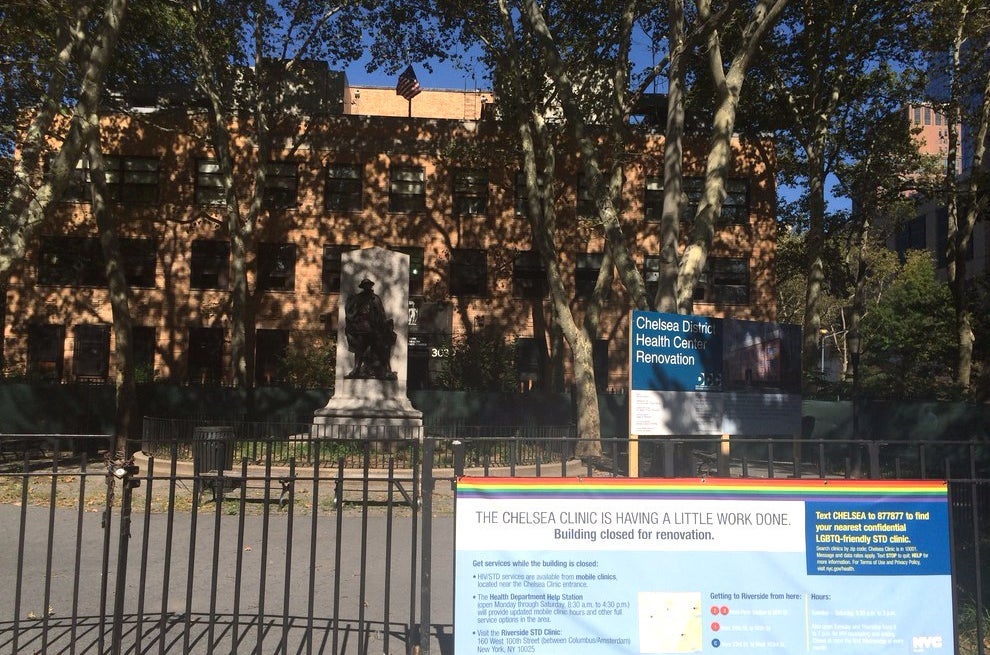

On March 23, New York City closed its most popular free STD clinic, in Chelsea, the neighborhood with the highest rate of HIV infections. The clinic is slated to re-open after a hefty renovation, but that's several years away. This follows the permanent closing of two less popular clinics — in East Harlem and Staten Island — in 2010 and 2013, respectively.

This abrupt closure of the Chelsea clinic spurred ACT UP to investigate the city's other efforts towards sexual health. On September 1 the organization will hold a town hall meeting to discuss what it calls "the indifferent and incompetent response of Mayor Bill de Blasio and his health department."

The city's actions are particularly disappointing, said Jim Eigo, a long-time activist with ACT UP, because of the statewide "Ending the Epidemic" campaign, investing some $10 million into testing, treatment, and prevention efforts. But the city, because of budget cuts, "is cutting back more and more and more," Eigo said.

HIV Tests At City-Funded Clinics From 2009-2015

From 2010 to 2011, city-funded HIV tests dropped by 36%.

Though they've fluctuated slightly since, the number of tests given in 2014 — at 212,701 — is still 110,000 lower than the 2010 figure.

This adds up to a cumulative loss of over 400,000 HIV tests given by the city since the drop began in 2010.

According to the city, there are many reasons for the drop in HIV testing. First, the budget for the Disease Control Division of DOHMH has been slashed from over $85.5 million in 2008 to $53 million this year.

"We're working really hard to undo the damage that has been done through funding cuts in New York City," Daskalakis said.

But city officials also argue that more individuals are seeking care through other means, diminishing the role of the free STD clinic as a testing provider of last resort.

That, Daskalakis argues, could actually be a good thing, as testing and treatment options become more well-distributed across the city. "The fewer people we have to pay for as a provider of last resort for HIV testing, the more successful we are in doing our job," he said.

Because non-DOHMH health providers do not need to report HIV tests that turn up negative, however, no city-wide numbers exist that can definitively say how many people are receiving testing elsewhere.

AIDS advocates don't agree with Daskalakis' assessment. They point out that the city's free clinics target high-risk groups — such as young gay men of color — who don't have private health care.

And testing is crucial for curbing the epidemic, especially when paired with recent pharmaceutical advancements. In 2012, the pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) drug Truvada debuted, which can prevent the spread of HIV.

Daskalakis was an early champion of PrEP, adding to New York City's legacy of making enormous strides in fighting the HIV/AIDS epidemic over the years. In 2012, for the first time since the early 1980s, when AIDS ravaged the city's gay population, HIV ceased to be on the list of top ten causes of death for people in the city. Rates of HIV diagnosis have fallen steadily, even in the last decade, from 5,496 in 2003 to 2,832 in 2013 — a nearly 36% fall.

But the success has slowed in recent years, and many advocates stress that now is not the time to reduce access to HIV tests, particularly for people with fewer options.

"I think it's safe to say that we aren't yet meeting the needs of the people who need it the most," Mitchell Warren, executive director of AVAC, a global HIV-prevention advocacy group, told BuzzFeed News. "I don't think we're there in New York City, or anywhere."

By closing free clinics, the city is making it more difficult for high-risk groups to get health care.

The Chelsea clinic, which saw nearly 20,000 sexual health visits per year, was the busiest of New York's nine remaining free STD clinics. The Health Department says it will re-open in two or three years, after a $17 million renovation of the nearly 80-year-old facility.

Chelsea's has an HIV diagnosis rate of 104 people per 100,000 — the highest in the city — and a syphilis infection rate that's six times higher than in the rest of the city.

Three months after its closure, in June, the city put a van in front of the closed clinic to direct people to nearby services, and another van from a community clinic is present to administer HIV and STD tests. Those vans can accommodate 10 to 15 patient visits a day, but according to city data given to ACT UP, only around 14 to 20 people stop by per week.

The Health Department has planned to divert $375,000 of additional funding to nearby clinics in hopes of helping them absorb some of the flow of Chelsea patients in need. But according to ACT UP's data, in the period since the Chelsea clinic closed, visits to free city clinics are down by 4,462 visits compared to the same time period last year — an 18% drop.

These cuts may be disproportionately affecting populations most vulnerable to HIV and other sexual health problems. About 74% of people diagnosed with HIV at free clinics in New York City in 2014 were black or hispanic, nearly 60% were under the age of 30, and 82% were men who have sex with men. Many of these individuals are the hardest to get to come into the clinic in the first place, advocates say.

"It's hard enough to get young gay men into health care, it's even harder when you're closing clinics," Perry Halkitis, a professor of global public health at New York University who focuses on HIV and AIDS, told BuzzFeed News. "The more difficult we make it to get care, the fewer people are going to access it."

The threat is not limited to HIV.

Since 2010, diagnoses of major STDs have been steadily rising among men in New York City. Syphilis is up by 33%, gonorrhea 43%, and chlamydia 17%.

Part of this, Daskalakis said, is attributable to the fact that more people are getting tested, and that, as technology advances, our tests are getting better at detecting infections.

Rates of syphilis and gonorrhea have also been rising in men nationwide.

"The way we control these illnesses is getting them into treatment," James Krellenstein, author of ACT UP's report, told BuzzFeed News. "It is public health malpractice to knowingly reduce access at these points of care."

Advocates argue that the drops in sexual health services run counter to the state's goal of slashing new HIV infections by 2020.

The state's Ending the Epidemic campaign aims to slash the number of annual HIV infections from 3,000 to 750 over the next five years. But AIDS activists argue that, at least in New York City, those goals are looking way out of reach.

Critics have noted that part of the problem is that the campaign is paying lip service without chalking up necessary funds. While some were expecting $100 million in funding, Governor Andrew Cuomo ended up allocating $10 million as part of his budget last year.

"New York's end-of-epidemic story is not about us getting from fair to good — we're going from good to excellent," Daskalakis said. "But am I going to take the criticism that we're not doing it well? Hell no. We're doing a great job and we're going to do a better and better job, whether it means with money or leveraging."

Update

This story has been updated to reflect that the new report came from both ACT UP and the Treatment Action Group.