Last year, the National Institutes of Health announced a new policy: With few exceptions, animal experiments funded by the $30 billion health agency must consider both males and females.

That may not seem like a big deal. Human trials have abided by this rule for two decades. But female lab animals — whether mice, rats, pigs, or rabbits — have historically been excluded from medical research. Their hormonal cycles, it was thought, could muddle the data.

The new NIH rules, which take effect in 2016, aim to remedy what many say was a shameful oversight in our seemingly balanced and objective scientific system. Studying both sexes, advocates say, will help address some of the very real health disparities between men and women, like the fact that young women who have heart attacks are twice as likely to die than their male counterparts.

“This isn’t something that was considered a priority by the establishment in the past,” Janine Clayton, the director of the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health, who is overseeing the policy change, told BuzzFeed News. “But it’s time for things to move forward in a different way.”

By and large, scientists have touted the new rules, calling it a “cataclysmic” change, a “valuable” turnaround at the NIH, and a “major victory" for women’s health.

But the policy also has many outspoken critics, who say that the change could produce misleading information about the differences between men and women.

In a commentary published this month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, four researchers argue that the new policy will not actually fix the health disparities between the sexes, because these differences are driven not only by biological factors, but social ones.

“Are we doing the right thing in investing in [animal] research when what we really need are these studies of how gender and sex interact in real life?” Sarah Richardson, professor of history and philosophy of science at Harvard, and lead author of the new commentary, told BuzzFeed News.

“I think it’s really important that the NIH is paying attention to the idea that there are health inequities that are preventable, unnecessary, and unjust,” added Nancy Krieger, a professor of social epidemiology at Harvard. “Does this policy get at that? No.”

These critics worry that putting so much emphasis on hard-wired sex differences in animals could lead scientists to draw misleading, or even harmful comparisons. "We feel this policy is putting into place a very broad mandate,” Richardson said, by requiring scientists to look for sex differences that may not exist in people.

Since the mid-19th century the default experimental subject was the “70 kilogram male” depicted in the famous medical textbook Gray’s Anatomy. Women wouldn’t enter the picture until more than a century later.

Beginning in 1977, the FDA decided that women “of childbearing potential” should be excluded from many drug trials — regardless of whether they were pregnant, or ever planning to be. That meant trials were done on men and their results were generalized to women.

But a growing women’s health movement saw this as paternalistic and potentially dangerous, and began to fight back, both within the NIH and in Congress. In 1990, the NIH formed its Office of Research on Women’s Health, with the goal of promoting policies and providing funding for research on the influence of sex and gender on health.

Three years later, the change was signed into law: From then on, the NIH, the world’s largest funder of medical research, was required to include women and ethnic minority groups in any clinical studies funded by the agency. The FDA, meanwhile, issued new guidelines recommending that pharmaceutical companies include more women in their trials as well.

Today, women make up more than half of the participants in clinical studies funded by NIH, though they are still often underrepresented in trials carried out by drug companies.

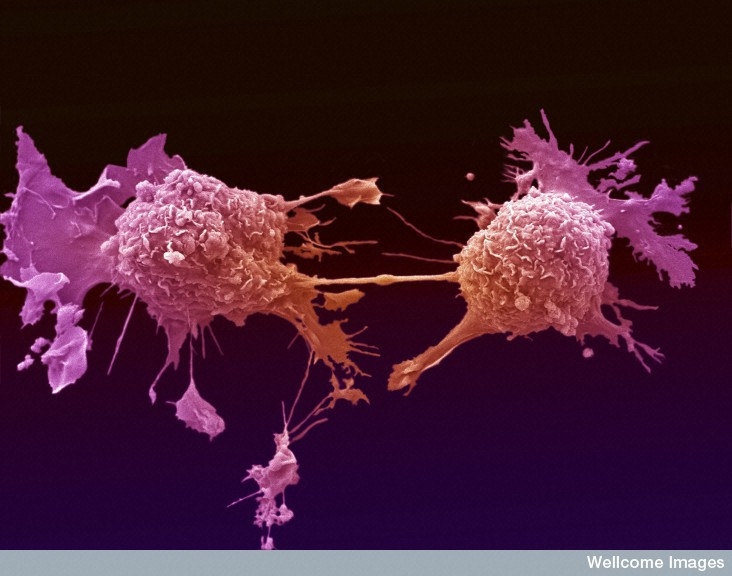

But the same cannot be said for so-called preclinical research — all of the experiments that come before a clinical trial, including studies of cells, tissues, and animals. In a 2011 survey of biology research done on mammals, for example, a male bias was found in 8 of 10 scientific disciplines. Pharmacology studies include five times as many male animals as female ones, and in neuroscience, single-sex studies of male animals outnumber female ones by 5.5 to 1.

That imbalance drove the NIH’s new policy. When Clayton and NIH chief Francis Collins debuted the idea in May, 2014, they wrote that the agency was going to tell scientists to perform experiments with a “balance of male and female cells and animals.”

“Every cell has a sex,” Clayton further explained to the New York Times. “Each cell is either male or female, and that genetic difference results in different biochemical processes within those cells.”

But some critics were appalled by the notion of cells and tissues — or even a fruity fly or a mouse — having a sex in the same way that humans do.

"Certainly we can say that an individual cell will have a certain set of chromosomes, but that isn’t the extent of what we mean when we say 'sex'," Stacey Ritz, associate professor of pathology and molecular medicine at McMaster University, told BuzzFeed News. "There are so many multifaceted, dynamic, and interactive aspects of what we understand sex to be at a whole body level that just aren’t present and can’t be present in a dish."

In the 18 months since the policy’s announcement, the agency has struggled to figure out exactly what experiments should look at sex differences, as well as how to pay for the additional experimental subjects.

By the time the rules were actually finalized this year, they focused only on grants for experiments on vertebrate animals and humans. The agency had quietly removed any language having to do with cells or tissues having a sex.

The NIH declined to comment to BuzzFeed News about when or why the policy changed its scope.

Even without the problematic language about cells having a sex, Richardson said, the policy is flawed. Animals are not always great models of human biology, and they certainly can’t model the gender differences driven by human culture. For example, women are more likely to take more than one drug at once. And in the case of heart attacks, which are often (erroneously) seen as a “male” disease, women are more likely to ignore their symptoms or hesitate in seeking care for fear of causing false alarm.

Sometimes human studies of sex differences are also plagued by faulty assumptions, Richardson notes, as shown by research done on the massively popular sleeping pill, Ambien. In 2013, the FDA slashed the dosage recommendations for women by half, after hundreds of women submitted reports of drowsy driving, sleep-walking, and even having sex while virtually asleep. Further studies indicated that women metabolized the drug more slowly than men did, though no one knew why.

Researchers figured it out only after looking at the drug’s effects in men and women: It was body weight, not sex, that drove the metabolic differences. “That’s why you have to study embodied human beings,” Richardson said.

Richardson’s concerns stem partly from the checkered history of the studies of sex and race. In 1854, a German anatomist named Emil Huschke concluded that the frontal lobe — which he called the “brain of intelligence” — was bigger in men than women. Similarly, supposed biological differences between races were invoked in 19th century Europe and the United States to justify slavery, for example.

“The minute you suggest that sex — or race, for example — is such a strong variable that you can expect to find differences everywhere,” Richardson said, “you end up institutionalizing in biomedical policy concepts of race and sex that suggest thoroughgoing differences.”

But researchers who study sex differences in animals vehemently disagree. “I reject that completely,” Jeffrey Mogil, a neuroscientist at McGill University, told BuzzFeed News.

Animal models aren’t perfect, he admits, but they are the best approach to making real medical advances. “Every single advance we’ve made in biomedicine has relied on animal models.”

In his own work, for example, Mogil has found that female mice process pain using an entirely different subset of cells than male mice do.

“Right now we have a situation where almost 70% of pain patients are women, and 80% of research subjects are male mice or rats — for no defensible reason,” Mogil said. “The NIH has tried carrots on this issue and that hasn’t worked, so now they’ve decided they’re going to try a stick. Frankly, I’m perfectly in favor of that.”

NIH’s Clayton emphasizes that the new policy is not asking all researchers to go fishing for specific sex differences. Rather, it’s trying to get them to recognize that ignoring sex as a possible influencing factor could lead to a skewed picture of reality.

Other leaders in the field of women’s health agree. “We will never understand what we don’t study,” Carolyn Mazure, director of Women’s Health Research at Yale University, told BuzzFeed News. “There is no good reason to ignore 51 percent of the population when conducting basic research.”