One week before my 7th birthday, I stayed up all night with the grown-ups. It was New Year's Eve in Fort Wayne, Ind., and our apartment was full of aunts, uncles, cousins, and family friends. The kitchen was where conversation came to a boil, bubbling over the top until someone had the good sense to manage the heat. I listened from various corners of the room. Each face was familiar, but the atmosphere was different. Parents were different when their children slept, and I was great at making myself invisible enough to watch the transition.

My mother's smile was so wide, the laughter fell from her mouth in a slant. I loved watching her like this. She looked warm and so happy. At 6, I knew my mother's life wasn't exactly easy. Our apartment was small, and her voice was big — so I knew that she was alone. When it came to family, all we had was each other. She deserved more. That New Year's Eve she looked like a woman who had more.

The easiest way for a child to lose their seat at the adult table is to speak. If no one hears your voice for long enough, they forget you're there. They let things slip. They say things they wouldn't normally say in front of a child. Even the adults who remember you're present will simply point a finger in your direction and make direct eye contact.

"You better not repeat any of this, you hear?"

I had no interest in repeating anything I heard. I was much more interested in bearing witness to all this freedom. Grown-ups seemed lighter at night, like their feet might hover an inch or two off the ground as soon as the sun went down. The later it got, the higher they flew. It didn't make me want to grow up faster; I was content to wait my turn. Even then, my childhood seemed precious and like something to cling to. I just wanted to watch and be awed.

My father was in prison and had been for as long as I could remember, but there were men around my family. My mother and her sisters were all either married or dating. At this party, there was one male family friend who wasn't around often, but I knew him. He was always smiling and slipping us dollars to spend on candy at the gas station. He was just as old as our uncles, but he actually spoke to us. As good as I was at being invisible, there was nothing I liked more than being spoken to like an adult. When he noticed me sitting quietly on the couch way past my bedtime, he caught my eye and winked. I smiled and waved back, happy to be noticed without being dismissed.

Right before midnight, the grown-ups got rowdy. Their eyes were wild, I was still invisible, but now they seemed to stop seeing each other. Someone turned on the TV so they wouldn't miss the countdown. Someone else almost knocked it over. I went into our dark living room to sit by myself for a while. I leaned against the patio door, trying to leave handprints on the cold glass.

"What you doing in here by yourself?" He was so nice, his voice didn't even startle me. I didn't answer, but started making more handprints all over the glass. I looked back at him and raised my eyebrows.

"See?"

He walked over, knelt beside me, and started making handprints too. At some point it occurred to me that my mother might not appreciate handprints all over her patio door, but if a grown-up was doing it with me, I figured it couldn't be all bad.

Noise from the kitchen swelled.

"Ashley, it's almost midnight. It's going to be a whole new year. What do you think about that?" I considered his question. I wasn't sure what happened at midnight on New Year's Eve. I hadn't stayed awake to see what would happen, I'd stayed awake to watch was already happening. I turned to him.

"I think it's good."

"It is good. Do you know what happens at midnight?"

I shook my head.

"At midnight, you kiss someone you love. Do you love me?" He was nice and he was like family. To me, that was enough to love.

I nodded.

He got close to my face and I pushed out my lips. Then the back of my head hit the patio door. I could feel the cold on my scalp while he used the force of his tongue to drive my lips apart and invade my mouth. His shaking hands were on either side of my head, and while my eyes were wide open, his were screwed shut. I thought I'd seen a kiss like this in a movie once, but it had looked nice. This was not nice. He was not nice.

Someone called his name from the kitchen and he scrambled away from me. I was glad. After a moment, I peeled myself away from the glass and walked past the kitchen. The grown-ups were all back on their feet, there was no floating. I found the only face I still cared to see glowing.

"Mama!" I rushed over to her. My mother looked down at me confused.

"Why are you still up? See you think you grown. Go to bed. Now."

Arguing was pointless. I should be in bed. I'd made myself visible, and that was the wrong thing to do. I headed up the stairs to my brother's room. I was older, but that was where I slept when I was scared. And I was scared.

I looked over to the kitchen one more time, ready to run back and plead with my mother to listen to me. Tomorrow would be too late. Tomorrow I would be asked why I didn't say something right away. Tomorrow I would be in worse trouble. I had to tell her what I did before she found out on her own.

Then he stepped into my line of vision.

"Happy New Year, Ashley." He winked. I did not wave.

I climbed the stairs and decided to forget about tomorrow, about telling her. Even if I was afraid, he was like family. And all we had was each other.

This is what happens to little black girls from poor families. I am certain it happens to other little girls too. It isn't hard for us to believe that our bodies and secrets are nothing more than collateral to keep peace and save face. We're taught when and how to be silent before anyone ever tells us we have the right to say no.

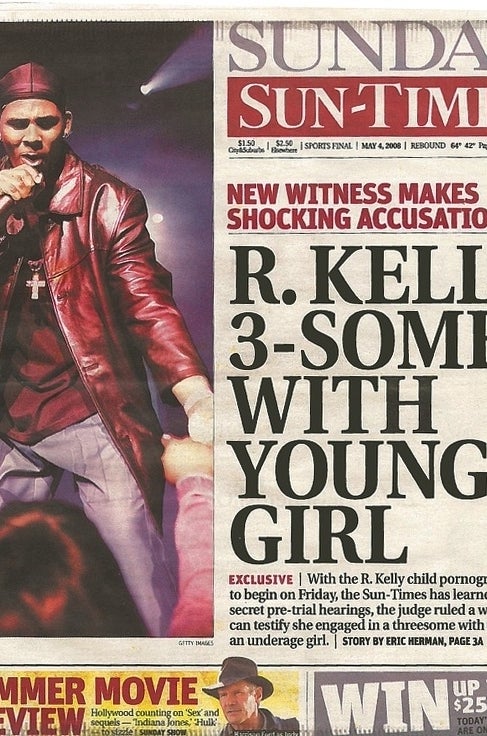

On Monday, Jessica Hopper released her Village Voice interview with Jim DeRogatis, one of the reporters who, nearly 15 years ago, broke the "stomach-churning" story of R. Kelly's history of preying on minors. It ignited a firestorm on my Twitter timeline. Most commentary came from women who corroborated the allegations against Kelly, people who couldn't understand how anyone still supported him, and hundreds of women sharing stories about being sexualized by adult men. Most of these women were black and grew up in working-class neighborhoods.

Initially, I saw the title and dismissed the article. We know who R. Kelly is and we know what he's accused of doing. There's a reason I don't buy his music. Then I saw the defenders and their comments coming through as they argued with the people I follow. The defenders always ask the same questions: How old is 14, really? Why didn't they tell anyone sooner if they were so innocent? Why didn't they say anything at all?

I don't know one woman who wasn't (at least) sexually propositioned by an adult man when she was somewhere between the ages of 9 and 18. Most of us didn't tell for fear of making a fuss. Some of us were blatantly told that men will be men, boys will be boys, and we just better keep our legs crossed. Who were we supposed to tell? Most of us experienced this for the first time during puberty. For others, the first time came even earlier.

When you ask, "Why didn't they tell?" you're not asking the right question. We don't tell for a myriad of reasons. When you ask, "Why didn't they think they could tell?" you'll be asking the right question. My silence was a symptom of various fears. In this, I am not alone.