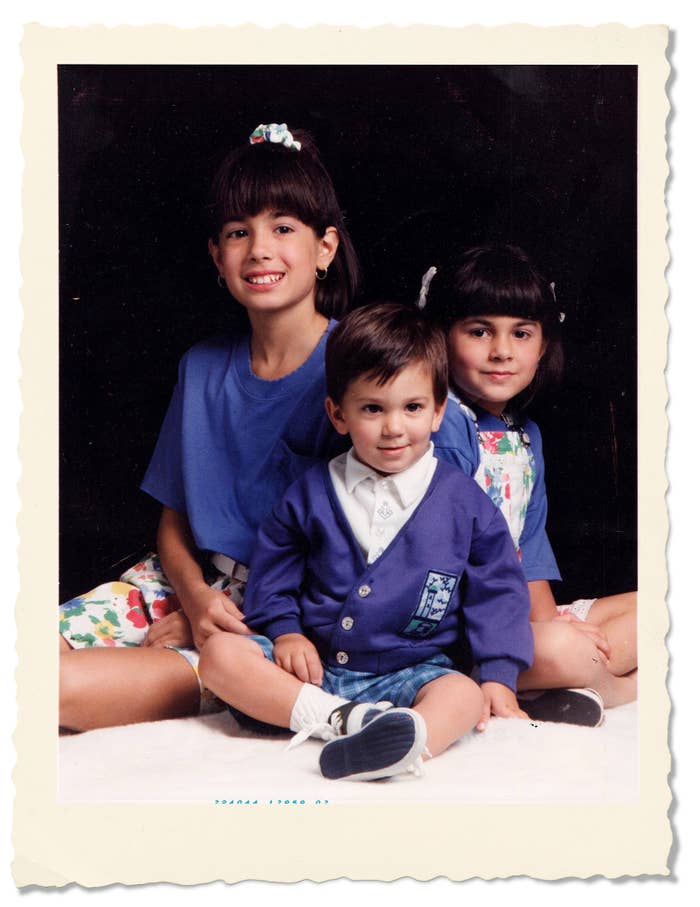

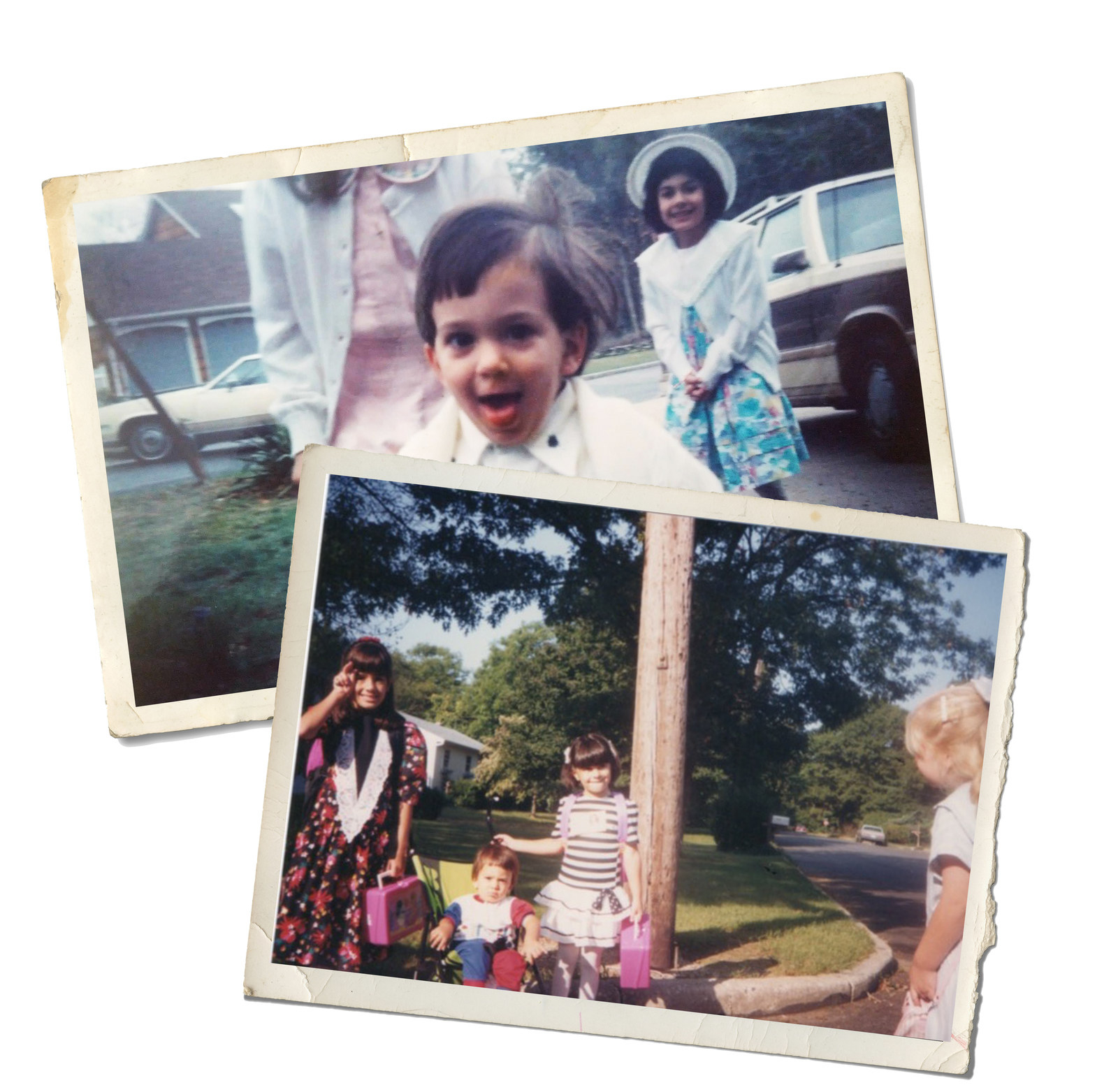

When my brother Jordan had been in the hospital for two weeks, with little improvement, my mom asked me and my siblings if we could bring him some photos. Recent ones, she said, maybe some with his friends. Her albums were filled with snapshots that are decades old now, and she wanted to present him with proof that he’d enjoyed life, and that he’d done so recently. “He’s convinced himself he’s never really been happy.”

“Is that possible?” I asked my therapist. “That we only thought he was happy?”

She shook her head. “He’s been happy.”

“But what if he’s never happy again?” I asked. “Is that possible?”

She paused.

“Am I allowed to ask that?”

She smiled. “You’re allowed to ask anything,” she said. And then, smile dropping: “But yes, it is possible. It’s incredibly rare, and it’s way too early to worry about that.”

So I gathered mementos: a custom photo book I’d designed for my grandma but then made copies of for my three siblings as well, with page after page of photos from hikes, bars, holidays, beach trips, a paean to our unlikely bond; a trail guide from that time we backpacked the west coast of Ireland with so little money we had to sleep on strangers’ couches; a rose quartz crystal Jordan had teased me about last Christmas. But the trail guide is spiral bound, so I had to leave it at the hospital front desk. And when I asked about the crystal, the nurse considered her answer, clearly torn, mouth twisted, but ultimately landed on no, for fear he’d try to choke himself with it. (“I’m sure he wouldn’t,” she assured me, apologetically. “But we can’t take risks.”) And when I handed him the photo book, he added it to a pile of other books — essay collections, meditation guides, fantastical zines — and I imagined it staying there.

Since I couldn’t bring him — or force him to look at — tangible memories, I tried tricking him into remembering by pretending I couldn’t, asking him questions that I hoped would force him to revisit his happiness, to believe in it. What was the name of the guy we sat next to at the bar in Ireland, the night we didn’t have a place to stay? Oh right, Jack, yes. And, okay, was he the one who took us to a weird beach with his friends? Like, middle of the night, totally empty? Yes, yes, of course — it was so fucking cold. The morning after that beach trip, we’d woken on the floor of this stranger’s living room and Jordan said it was one of the top five experiences of his entire life. Now, he confirmed the details without emotion.

“I want to say, ‘Jordan, are you in there?’” my sister told me as we left the hospital one day. Where was he now? Would he come back?

“Recall, remember,” Sylvia Plath once wrote in her journal, days after describing why she wanted to kill herself, and 10 years before she would. “Please do not die again.”

We rely on memory to tether us to the good. We curate the happiest moments of our lives and our selves in photo albums, on social media, in the pages of scrapbooks; they are the ropes we toss into the abyss of depression so that, if or when we’re there again, we might climb back out.

So many of the moments Plath recorded in her journals were celebrations. She rejoiced in her stories and poems being published, in her talents earning both praise and professional opportunities. She shored up her resilience by writing of suicidal lows that had passed, of her confidence in her ability to prevent another from returning. She was curious about art and research and those around her; her analyses of the works of her contemporaries vibrate with life. She had the capacity for joy, and she knew this — but she was terrified of losing it. She saw the moments in which she couldn’t access this joy as evidence of her forgetting it, and that, if forgotten, such joy might as well have never existed at all. In even the briefest experience of doubt or despair, Plath saw a threat of joy’s permanent retreat, and the only work she could do against this outcome was tying joy to the page, refusing to lose happy memories to time lest she come to doubt they had ever happened at all. “Sometimes, in a panic, mind goes blank,” she wrote. “The world whooshes away in a void, and I forget the moments of radiance. I must get them down in print.”

We rely on memory, too, to recognize and avoid the bad, as if experiencing it once and recording it faithfully is enough to banish it for good.

Plath described herself in multiple accounts as “clinging” to her past, a word that evokes the desperation of a person who is certain her survival depends upon it. It’s easy to understand why. If a person lives in perpetual fear that the self she is in one moment will be lost to and forgotten by the self she becomes in the next, wouldn’t she want to leave that future self reminders of who she’s been — of who she really is? Plath wrote memory like an incantation, hoping that by capturing remembered feelings and experiences in writing, she might conjure them back. “Remember, remember, this is now, and now, and now. Live it, feel it, cling to it.”

But we rely on memory, too, to recognize and avoid the bad, as if experiencing it once and recording it faithfully is enough to banish it for good. Just weeks after her first mention of considering suicide, Plath pushes herself to record the details of her highs and lows; she “stay[s] up late in spite of vowing to go to bed early, because it is more important to capture moments like this, keen shifts in mood, sudden veerings of direction.” Virginia Woolf, following a bout of career-related depression, insists in her journal that she must “note the symptoms of the disease so as to know it next time.”

But I’m not so convinced this is all for the purpose of recognizing another low when it returns. We write it to distance ourselves from it, to forsake it, to convince ourselves we are so distinct in our wellness from that depressed person that another low won’t, couldn’t possibly, return. We separate from it so we might examine the self in the midst of a low and say: Look at her. Look at how she hides the evidence of her midday hours-long naps. Look at how her eyes glaze over in the middle of a conversation. Look at how she retreats in corners, in beds.

“Look at that ugly dead mask here and do not forget it,” Plath wrote next to a photo of herself that she’d glued inside her journal. “It is what I was this fall, and what I never want to be again.”

One year before Jordan checked in, almost to the day, I chose a hospital stay over suicide, and was rehabilitated over the course of seven days in a different psych ward. Different factors brought us in, but we understood the same deep emptiness and despair. So when he asks me, crying, “Did you ever lose interest in writing?” I say yes, even though my first thought is no.

I don’t remember losing interest in writing, and I can’t decide if this is a good or bad sign, if it’s evidence that I’ve come so far out of my low as to have forgotten its details, or if it means Jordan is in a low I’ve never reached, which is to say a low I’ve never survived. But then, I wasn’t writing, at my worst. Maybe I wanted to, or maybe I felt like I had to, but I couldn’t even fathom doing it. I’d lost interest in living, which means I’d lost interest in all of those things that made up my life. So I say, “Yes, of course. But honestly, the way you feel now — doubting you ever felt happy, because you can’t remember feeling it — that’s how I feel, but about how depressed I was last year. If it makes you feel better.”

I take his hand and I say, “Make a list of all the things you thought you enjoyed, even if, now, you can’t remember what it felt like.” I don’t believe he’ll feel that happiness by remembering it — that’s never worked for me — and yet I can’t help but convince him to do it. Because what else is there to do? Maybe the knowledge that he’s been happy before might be enough to convince him he’ll be happy again, might be enough to convince him to keep going. Maybe memory is more of a buoy than a rescue boat — not enough to bring him to safety, but enough to keep him afloat while he waits for whatever can. But there is so much pain in the waiting, the fear in not knowing how long the pain will last this time. Who knows when that rescue will come?

Plath knows this — that a moment experienced is more valuable, more real, than a moment remembered — even while she fights it. “Nothing is real except the present,” she writes, which, I suspect, is why she’s so intent on carrying her past with her, on trying to make it an active part of the present. Woolf understands this, too. The past is embedded in Woolf’s present, but not because she invokes it or forces it there; the past acts upon her from wherever it remains, alive in its own right: “Is it not possible — I often wonder — that things we have felt with great intensity have an existence independent of our minds; are in fact still in existence?”

Memory, for Woolf, is not only what one has remembered; “it is also what one has forgotten.” Remembering is insufficient because it isn’t reliving, and journaling can’t replace that lived moment. But still she yearns for it, dreaming of a device that will “get ourselves again attached to [past emotion] so that we shall be able to live our lives through from the start.” In Woolf’s utopia she can literally spend her present in her past; she can swap her current being with one of the many that preceded it.

Where all of this leads: The intensity of a person’s death grip on the past is directly related to the strength of their fear of the future, which is tied to a distrust of the present. It isn’t around long enough to believe in. “This second is life,” Plath writes. “And when it is gone, it is dead. […] The high moment, the burning flashes come and are gone, continuous quicksand. And I don’t want to die.” If we allow the present to amount to a ceaseless series of deaths, then survival must depend on refusing to let memory die — in other words, spending the present reliving the past. If we fear the passage of time, what better way to deny it than diving into that quicksand? Woolf frantically writes a similar fear: “Life piles up so fast.” If the past is quicksand, sinking, or if it is an ever-increasing heap, then living in it will either pull us down or crush us. Either way, we’re stuck.

For six weeks I existed in a state of liminality, checking into one hotel after another, setting up temporary homes in rooms ranging from mold-ridden to near-luxurious, depending on how self-indulgent I felt when I booked them. I could tell myself and everyone around me that I was doing this because Jordan’s hospital was a 90-minute trip from my Brooklyn home, and staying close to him made it easier to be there during daily visiting hours. I could say this and it would be true but incomplete. I knew I didn’t have to do this. I didn’t have to fall deeper into credit card debt in order to support him. I didn’t have to scramble for Wi-Fi so I could call into work meetings, didn’t have to take sick days and then vacation days when I realized I couldn’t keep up. I didn’t have to drive from hotel to hospital to home and back again, over and over and over. “You know he’d understand if you have to take a break,” my mom told me. I knew she was right.

There can be comfort and relief in the stasis. But that comfort can become dangerous without warning.

Mostly I did it for myself. My life was paused because I couldn’t emotionally separate myself from Jordan, sitting in that common room 18 miles away. During the one week that I tried to handle everything from home — when I tried going back to the office, waking up early, doing my stretches, trusting my family to visit him on the days I couldn’t get on the train — it took just two days for me to end up crying on my living room floor. I called my sister from down there, my phone resting on the hardwood panel next to my head, my body splayed like a starfish. “You know those videos of dogs who freak out when you put those snow booties on them? And they just look too terrified to even take a step?”

She did.

“That’s what I feel like. I’m a little dog stuck in booties.”

She understood, and it helped, for a bit. It was permission to go through the motions without feeling quite present, to get up and get dressed and go to the office and answer emails because that’s what they pay me to do. And the next morning I got up, but was paralyzed in front of my closet, the second step too daunting to face. And I messaged my team to say I was working from home, and I went back to bed, and I woke up three hours later to messages from my boss, and I thought, for the first time in months, that knee-jerk reaction to feeling overwhelmed: Well, I should probably just kill myself.

I booked another four nights at a hotel that night. I wasn’t home for more than two nights a week until he got out.

My life was paused because I wasn’t able to move forward — at least not in the way I’d come to define forward progression — and I needed my environment to match my emotional and functional suspension, to in fact necessitate it. There is only so much you can do from a hotel room in an unfamiliar town, and the bulk of it is ordering room service, going shopping, taking baths, watching movies, reading books. It was an acceptable, which is to say forgivable, pause button, an approximation of a functioning person in a functioning life, a way of shutting down while pretending that I wasn’t. There can be comfort and relief in the stasis. But that comfort can become dangerous without warning: self-destruction disguised as self-care.

Recording, revisiting, reworking the past guarantees a kind of stasis, at least when done with the intensity of Plath and Woolf, and, if I’m being honest, me. I suspect this, if even subconsciously, is the root of our compulsion to do it. It is inaction masked as its opposite. Filling pages of a journal sure feels like productivity, until the writing of having done supersedes the doing, and our imagining the future keeps us from working toward realizing it. This dream of the future is inseparable from our obsession with the past, because the integral part of archiving is imagining the unknowable self who will read it years down the line. The self who, we swear, will have banished her badness, will luxuriate in her success, will have finally mastered the great truth of existence. And how quickly this daunting, perfect, impossible self becomes a hindrance to even moving toward her.

What happens when that dream of a future is suddenly the present, and it hasn’t brought with it all of the clarity and success we imagined?

Plath’s fear of the future manifests as indecision. She sees each choice as a narrowing of the expanse of options before her, and she is paralyzed by her inability to see all possible ends before deciding. “Life is so only-once,” she writes, “so single-chancish!” It is frightening to believe that our decisions have permanent consequences, and terrifying — to the point of paralysis — to imagine that one possible consequence could be a fatal, suicidal despair.

Woolf revels in her future self, fixating specifically on Virginia aged 50. She writes about and to this self, relishing the eventual rereading of her entries more than the present writing of them. “How I envy her the task I am preparing for her!” she writes a week before turning 37. “There is none I should like better.” This future self will know her better than she knows herself, now; she will be able to look back at what Woolf envisioned as she wrote and “will be able to say how close to the truth [she] came.” She romanticizes the past and idealizes the future — where she resides, in the present, can never live up to either. What happens when that dream of a future is suddenly the present, and it hasn’t brought with it all of the clarity and success we imagined? I don’t know if Woolf was disillusioned when she became her 50-year-old self, but I do know she killed herself nine years later.

“Nothing is real except the present,” Plath writes, but the meaning shifts with her moods. Most often she engages the idea in bad faith: dissolving the future, failing to acknowledge that the future is just a present she hasn’t reached yet. She invokes it only in moments when her present is pain, and talks herself in circles: “Nothing is real, past or future, when you are alone in your room with the clock ticking loudly into the false cheerful brilliance of the electric light. And if you have no past or future, which, after all, is all that the present is made of, why then you may as well dispose of the empty shell of present and commit suicide.”

But there is so much more possibility in the statement. If we choose to believe that the present is all that matters — if we invest in believing this — we cede the possibility of shoring up our resilience with past happiness, but we also free ourselves of the paralyzing fear of future failure. It’s a worthy goal. We might work toward experiencing the past and future only passively, rather than intentionally — a triggered memory, scheduling a future event. We might give both less weight, relieve ourselves of the burden of carrying not only our history but every imagined future. Every hypothetical life. We could welcome, instead, a lightness, even a freedom. What if the present were enough? Which is to say, what if I, now, were enough?

I arrive at the hospital and my mom is already there, sitting next to Jordan. She looks up at me and smiles in the way that means it’s not a good day. I squeeze his shoulder and sit down, but he’s got his hood up and I can barely see his face. His hand rests on a piece of paper, a large brown oval with jagged edges painted just off-center. “What’s this?” I ask.

“He had art therapy this morning.”

“Oh, cool, did you like it?” He shakes his head. “I loved art therapy. One time, one of the guys, older, really shy, painted these blue and purple figures — they kind of looked like trees? And when the counselor asked what he was working on, he said, really quietly, that they were friends and the purple part was their love. I swear it’s the only thing I heard him say the whole time.”

“I love that!” My mom says. She squeezes Jordan’s hand. “Isn’t that sweet?”

He starts to cry, and I try not to.

I pick up the painting. The brush strokes are short, doubling back on themselves; it’s a violent cover-up of his first attempt, now visible only as a bright specter behind a rust-colored veil. “Can I take this?” I ask, and he nods. And I take it home and store it in my desk drawer, under a pile of unused and abandoned planners. And I think, I’ll show you this when you’re past this. You’ll look at it, but it won’t mean anything. You won’t even remember what it felt like to make it. ●

If you are thinking about suicide or just need to talk to someone, you can speak to someone by calling the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255). And here are suicide helplines outside the US.