Fiction

The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead (Doubleday)

In this magnificent novel, Whitehead once again draws inspiration from true atrocities of America's past, this time creating a fictional account of a real-life Florida reform school for boys that was infamous for torturing and killing its poor black students, and then secretly burying their bodies, in the 1960s. Whitehead builds his story around Elwood Curtis, an ambitious, socially conscious, law-abiding teenager in Tallahassee who gets into the wrong car on his first day of elective community college classes and winds up arrested for auto theft. His sentence is enrollment at the Nickel Academy — which, despite its solid reputation, turns out to be built on cruelty, racism, and corruption. As Curtis discovers that his good behavior and best intentions won't be enough to keep him safe, his worldview shifts, and survival becomes more of a strategy. Whitehead's prose is meticulous; he nimbly shifts between the 1960s and present day, creating a fully fleshed-out picture of violence and (in)justice with a finale that just guts you. —Arianna Rebolini

Olive, Again by Elizabeth Strout (Random House)

In a year of hotly anticipated sequels, Strout’s Olive, Again was simply the best of the bunch. Using the same interrelated short story framework as she did in her 2008 Pulitzer Prize–winning predecessor, Strout revisits the fictional town of Crosby, Maine, and its inhabitants some years after the events of the first book. We find retired school teacher Olive Kitteridge still as cantankerous as ever, as she and other residents grapple with aging, sickness, and life’s general disappointments. Nobody can casually devastate like Strout can; the secret is that she writes with such humor and such grace that you don’t even realize you’re tearing up until the book is over. —Tomi Obaro

Gingerbread by Helen Oyeyemi (Riverhead)

Oyeyemi’s latest beguiling novel tells the story of Harriet and Perdita Lee, an oddball mother–daughter duo who lives in London and makes delicious gingerbread — a family recipe supposedly quite popular in Harriet’s (possibly fantastical?) homeland of Druhástrana. As daughter Perdita grows older and more curious about her mother’s mysterious upbringing, she digs into the past and ferrets out a thorny family legacy. It's everything Oyeyemi does best — funny, dreamy, vast, and just a tad eerie. —A.R.

Read the first chapter here.

On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong (Penguin Press)

Already one of the most celebrated poets of his generation, Vuong’s debut novel cements his considerable talent. Formatted as a letter addressed to his illiterate mother, Vuong’s narrator, a queer Vietnamese American writer not unlike Vuong, crafts indelible images — a young mother staring down the muzzle of a gun in Vietnam, an unexpected act of kindness in a schoolyard, purple flowers stolen from the side of a highway. An exploration of generational trauma, of violence, of addiction, of poverty and of beauty too, every word in this book feels written with such care. A truly memorable fiction debut. —T.O.

Read a poem by Vuong here.

Nothing to See Here by Kevin Wilson (Ecco)

I started Nothing to See Here at the very beginning of my maternity leave, that destabilizing time when you’re suddenly living with a crying newborn who doesn’t know the difference between day and night, and when every minute of sleep is a gift. That I chose this book over naps more than once is a testament to my love for it. It probably helps that it’s a story about family — specifically, new and terrifying (if nontraditional) parenthood. When deadbeat Lillian agrees to play governess to her rich best friend’s twin stepchildren (who happen to spontaneously burst into flames) she has no idea what she’s doing, and certainly has no understanding that it could profoundly change her. But it does — and this small, weird, quasi-family’s summer together is equal parts hilarious and moving. —A.R.

The Old Drift by Namwali Serpell (Hogarth)

Spanning more than 100 years, from 1874 to 2024, Serpell’s enchanting debut novel is epic in every sense of the world. Three families — one white, one Indian, and one black — converge near Victoria Falls in what will eventually become Zambia. Melding historical fiction, magical realism and Afrofuturism, Serpell charts the fortunes of these families through their tumultuous ups and downs alongside the country’s. It’s a wonderful achievement, reminiscent of Salman Rushdie at his best and the tales of Gabriel García Márquez and Isabel Allende. —T.O.

Read an essay by Serpell here.

The Organs of Sense by Adam Ehrlich Sachs (FSG)

At its core, The Organs of Sense is about a 1666 encounter between a young Gottfried Leibniz and a blind astronomer who makes the unlikely prediction of a solar eclipse, but it's also about the astronomer's magical history, as relayed to Leibniz. These stories — about art and reality, genius and insanity, fathers and sons — drive the narrative and are encapsulated by the narrator's own recounting of the three-hour encounter, referring frequently to Leibniz's later writings on their meeting. It is at once a pitch-perfect send-up of an overwrought philosophical tract and a philosophical tract in its own right — meaty, hilarious, and a brilliant examination of intangible and utterly human mysteries. —A.R.

Women Talking by Miriam Toews (Bloomsbury)

Toews accomplished something really remarkable with her seventh novel; she managed to write a book that feels both timely and timeless. Based on a horrific real-life crime, women in a remote Bolivian Mennonite colony deliberate about what to do after discovering that they have been repeatedly drugged and raped at night over the course of several months by men in their own community. Fluent only in Low German and unable to read or write, the women rely on August Epp, a disgraced former member of the colony, to record the minutes of their secret meeting determining their fate. Should they stay and live with the men who hurt them? Or should they take their children and flee? Exploring fundamental philosophical questions, such as what punishment and forgiveness look like, Women Talking is one of those books that feels destined to become a classic. —T.O.

Read our profile of Miriam Toews.

Machines Like Me by Ian McEwan (Nan A. Talese)

McEwan’s latest novel exists in an alternate version of 1980s UK, one in which Alan Turing is still alive and his work has accelerated technological achievement. In this world, things like smartphones, social media, AI, and self-driving cars already exist; the hottest gadget is the first limited run of prohibitively expensive synthetic humans, which disillusioned thirtysomething Charlie Friend just has to have. Enter Adam: externally indistinguishable from any other living man, housing a “brain” that develops into something unnervingly close to consciousness. Machines Like Me manages to add something new and provocative to the well-worn territory of human vs. robot dynamics, and his weaving Adam into a love triangle allows the book to delve into urgent questions not only about responsibility in innovation, but also art, humanity, and morality. —A.R.

Patsy by Nicole Dennis-Benn (Liveright)

Dennis-Benn has the uncanny ability to create characters that feel deeply, painfully real and the people in her second novel are no exception. Patsy, a queer Jamaican woman in love with her best friend Cicely, leaves her 5-year-old daughter in the care of her religious mother, to go to New York to find Cicely. Suffice it to say, all does not go according to plan, as Patsy learns the hard way what life in America is like as an undocumented immigrant. Meanwhile, Tru, who is still figuring out her own gender identity and sexual orientation, tries to adjust to life without her mother. A compulsively readable book that deftly grapples with maternal ambivalence. —T.O.

The Book of X by Sarah Rose Etter (Two Dollar Radio)

This book is dizzying and grotesque — and I say that with the utmost love. It's an astute exploration of humanity and the body — specifically the female body — through the lens of young Cassie, who continues in a long line of women born with their torsos twisted into a knot. Cassie hates her knot profoundly; it becomes the focal point of her loneliness, insecurity, and pain, both physical and existential — all of which is compounded after she experiences a traumatic assault. Etter has built an eerie, surreal world — the Earth is literally built of flesh; Cassie's father makes a living reaping tender cuts from the "meat quarry" — and she seduces you into it with dreamy lyricism. You won't want to leave. —A.R.

The World Doesn't Require You by Rion Amilcar Scott (Liveright)

It’s hard to think of a more original short story collection this year than this genre-agnostic one. Focused primarily around the men in a fictional Maryland town called Cross River, the site of a slave insurrection, the characters in this sophomore collection act out, make robots, write lengthy dissertations, and play a particularly dark version of dingdong ditch. The last story, a novella about a professor slowly losing his mind, is trenchantly funny and compelling. —T.O.

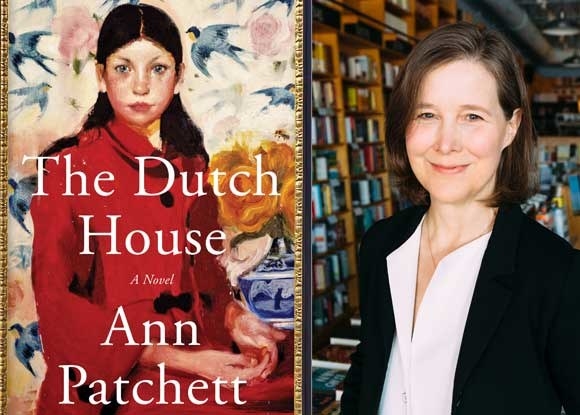

The Dutch House by Ann Patchett (Harper)

Patchett's latest is a rich and evocative story of family and place — the relationships that define us and how they change over a lifetime: the emotional weight of physical spaces and the specific power of those we inhabit in our youth. Here that space is the eponymous Dutch house, the ostentatious mansion at the center of our narrator's very identity; every element of his life — the loss of his mother, his dependence on his sister, his career and values — can be traced to his father's baffling decision to purchase it. It's a story of the endless and impossible search for meaning, written in beautiful, quiet prose. —A.R.

Your House Will Pay by Steph Cha (Ecco)

Known primarily for her mystery novels, Cha uses a real-life event — the murder of 15-year-old Latasha Harlins at the hands of a Korean store clerk, and a precipitating cause of the 1992 LA Riots — as an impetus for an exploration of the lives of two families, one Korean and one black, who are still reeling from a similar incident that happened decades ago. Cha’s characters feel convincingly real. You ache for their pain and hope for their closure. —T.O.

Fly Already by Etgar Keret (Riverhead)

Keret’s stories range from dark to downright silly — there’s the child in the title story who misunderstands the intentions of a man standing on the roof of a tall building, the strangers who meet up daily after work to share a joint on the beach, the increasingly absurd email exchange between a man desperate to bring his mother to an escape room that is unfortunately closed, and the owner of said escape room with a pretty big secret to hide. Each is beautifully wrought and rife with meaning — and slightly maddening in its ambiguity. —A.R.

Sooner or Later Everything Falls Into the Sea by Sarah Pinsker (Small Beer Press)

Pinsker's debut short story collection is speculative and strange, exploring such wide-ranging scenarios as a young man receiving a prosthetic arm with its own sense of identity, a family welcoming an AI replicate of their late Bubbe into their home, and an 18th-century seaport town trying to survive a visit by a pair of sirens — all while connecting them in a book that feels cohesive. The stories are insightful, funny, and imaginative, diving into the ways humans might invite technology into their relationships. —A.R.

Everything Inside by Edwidge Danticat (Knopf)

The eight stories that make up fiction master Edwidge Danticat’s latest collection hover around Haiti and those who've left it, delving into the lasting effects of migration and displacement on families and individuals, and written with the kind of emotional precision that leaves you gasping. We meet a young woman whose first and last encounter with her father is at his deathbed, a hardworking nurse who dips into her savings to help her ex-husband's new wife, a mother fighting dementia long enough to dispense wisdom to her daughter — a whole cast of characters who feel absolutely real: so striking in their ordinariness, so complex in their humanity. —A.R.

The Tenth Muse by Catherine Chung (Ecco)

Chung, a former math major at the University of Chicago, leans on her own real-life aptitude for math in her sophomore novel about a talented mathematician named Katherine whose attempt to solve the Riemann hypothesis uncovers secrets about her family's past. Nearing the end of her life, Katherine looks back at all she's been through, beginning as one of the few women graduate students at MIT in the 1960s, meeting and befriending some of the world's greatest scientific minds, but never being able to shed her role as an outsider amid the boys club. Woven throughout her professional research, though, are Katherine's inquiries into her own history as she discovers that her parents might not be who they seem to be. It's an interrogation of truth and its value — of secrets, sacrifice, and identity. —A.R.

All This Could Be Yours by Jami Attenberg (HMH)

A family that isn’t exactly devastated by the death of their patriarch is an intriguing family indeed in Attenberg’s latest novel, set in New Orleans. An easy-to-read book about a complicated family — Attenberg’s area of expertise. —T.O.

Read the first chapter here.

The Topeka School by Ben Lerner (FSG)

Lerner’s highly anticipated third novel is a nuanced but damning portrayal of masculinity and whiteness in the US, built around Midwestern teen (and debate champion) Adam in 1997, his last year of high school. The story radiates around him, jumping around time, perspective, and even narrative format. Adam’s parents are, like the parents of most of his best friends, therapists at a local psychiatric institute called The Foundation, and each person’s understanding of themselves is colored by the rhetoric of psychoanalysis as well as its failures: A person can learn how to identify and articulate the underpinnings of their rage and still act on it anyway; at worst a person can weaponize the very language meant to broaden understanding. Dealing with themes of abuse, betrayal, and prejudice, The Topeka School is at once a personal and national reckoning, and impossible to put down. —A.R.

Lot by Bryan Washington (Riverhead)

Washington’s debut short story collection is an ode to Houston and a vibrant portrait of the myriad people who call it home. The stories circle around a young boy figuring out his sexual identity while holding down a job at his family’s restaurant; around him, a city of creators, survivors, and hustlers vibrates with life. Washington’s effervescent prose draws the reader into the fold — his use of first person, especially plural first, can read like a generous inclusion — as his characters explore family, community, new freedoms, and love. —A.R.

The Man Who Saw Everything by Deborah Levy (Bloomsbury)

In many ways, 2019 was a year of fiction that kept us on our toes, full of ambiguous narratives, unexpected formats, and narrators ranging from coy to downright misleading. In The Man Who Saw Everything, Levy drops hints that this story might not be as straightforward as it initially seems. It begins in 1988, when 28-year-old British historian Saul Adler is hit by a car while waiting to take a photo at the iconic crossing on Abbey Road. The photo is meant to be a gift to the German family he’ll be staying with on his upcoming trip to East Berlin, as part of his research into fascism and its opposition. Saul can be a grating protagonist — dismissive of those who care for him, myopic, and unforgiving. This is the irony, of course, of the title: He can’t see much beyond himself, and understands little of his own desires. But by revealing just how much Saul doesn’t know, Levy is able to explode narrow ideas of sexuality, morality, and even time, exploring the vast possibilities of the human experience. — A.R.

In West Mills by De'Shawn Charles Winslow (Bloomsbury)

It's impossible not to fall in love with Azalea "Knot" Centre, the star of In West Mills, whom we meet as a hotheaded 27-year-old bachelorette in North Carolina in 1941. Her boyfriend keeps proposing, and her well-meaning neighbor Otis Lee begs her to accept, but Knot is more interested in working, drinking, and enjoying her own company. Knot's sense of independence and identity is rattled, though, when a hookup leads to a baby she doesn't want — and the aftermath resonates for decades. In West Mills follows Knot, Otis Lee, their families, friends, and neighbors, from 1941 to 1987, exploring the bonds of friendship, the weight of secrets, and all the sacrifices we make in our attempts to live a self-determined life. —A.R

Nonfiction

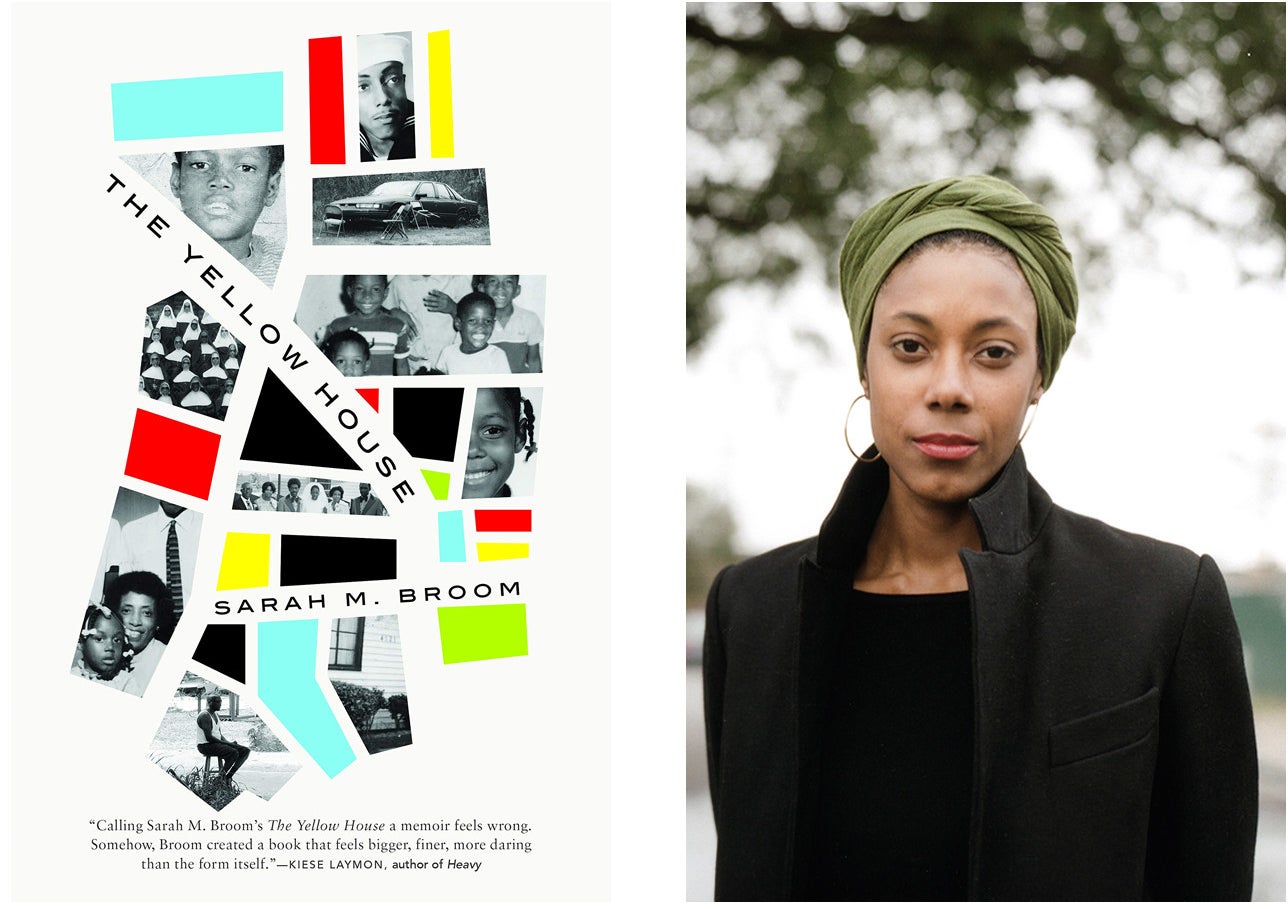

The Yellow House: A Memoir by Sarah M. Broom (Grove Press)

Exquisitely written and incredibly self-aware, Broom’s tribute to her family and the house she grew up in, located in New Orleans East, an often- neglected part of the city devastated by Hurricane Katrina, feels canonical. Broom, the youngest of 12 children, uses her journalist training to excavate her family history, relying on interviews and historical records to create a compelling story about a black working-class family struggling to make ends meet. When Hurricane Katrina, or the Water, as she refers to it, hits, she paints a harrowing picture of those anxious days waiting to hear from her family members. She also places her family’s story within the larger history of New Orleans, stripping the city of its mythos and thus making this memoir more ambitious, more definitive than most memoirs typically are. An extraordinary achievement. —T.O.

Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland by Patrick Radden Keefe (Doubleday)

Where was Jean McConville, mother of 10, recently widowed, taken one winter night in Belfast in 1972? Part mystery and part (riveting) history lesson, this deeply reported book reads like an expertly plotted novel. New Yorker staff writer Patrick Radden Keefe spent four years researching this definitive account about the Troubles, the period between 1969 and 1998 when skirmishes between Protestant loyalists, who want the predominantly Protestant Northern Ireland to stay a part of the UK, and Catholic Republicans, who yearn for a united Ireland, reached a troubling, violent fever pitch. Charting the rise, and in some cases ignoble fall, of some of the Provos IRA’s most famous leaders, while also following up with the McConville children years later, Keefe contextualizes a fascinating moment of world history, while making clear the human cost and psychic toll of decades-long war. —T.O.

Survival Math: Notes on an All-American Family by Mitchell S. Jackson (Scribner)

The “survival math” of Jackson’s memoir refers to the necessary calculations he and his family made daily to ensure their safety in their small black neighborhood in Portland, Oregon — one of the country’s whitest cities, a city whose anti-blackness was written into its constitution — that was plagued by gang violence and ignored by the government. Interspersed with "survivor files" recounting the stories of his male relatives, Survival Math explores issues like sex, violence, addiction, community, and the toll this takes on a person’s life. It’s an extensively researched and illuminating look at the city of his childhood, at turns hopeful and heartbreaking. —A.R.

Read an excerpt here.

The Queen: The Forgotten Life Behind an American Myth by Josh Levin (Little, Brown and Company)

Levin provides an exhaustive and thoughtful account of Linda Taylor, the prolific criminal whose notoriety gave rise to the trope of the “welfare queen.” By digging into Taylor’s history — which, there is no doubt, is riddled with fraud, theft, and possibly wrongful death — Levin sheds light on the systemic anti-blackness throughout the US that allowed politicians to so easily turn a woman into a caricature and then use that caricature as justification for maligning, at once, black Americans and the welfare system. It’s a tale of racism and greed — consider, Levin asks, why the cops who worked so tirelessly on outing Taylor’s manipulation of the welfare system would suddenly lose interest when a black woman in her care died of unknown cause — and a fascinating piece of true crime. —A.R.

Good Talk: A Memoir in Conversations by Mira Jacob (One World)

The ultimate rejoinder to those asinine roundups about how to talk to your conservative family members about politics, Jacob’s graphic memoir is a charming, moving account of what it’s like raising a brown child with Trump-voting in-laws, of growing up as a dark-skinned Indian American in a white town, and of self-discovery and growth. —T.O.

Read an essay by Mira Jacob here.

The Collected Schizophrenias: Essays by Esmé Weijun Wang (Graywolf)

In this frank, thoughtful collection, Wang considers the weight of a schizoaffective disorder diagnosis. She documents her first experiences with hallucinations, her humiliating experiences being held involuntarily in psychiatric wards, and the devastating effect of having what she’s convinced is the controversial late-stage Lyme disease. Throughout her writing, she risks easy sentiment and shows us how pop culture depictions and history have contributed to so much misunderstanding around mental illness. It’s an engaging, important read. —T.O.

Check out an excerpt here.

Wild Game: My Mother, Her Lover, And Me by Adrienne Brodeur (HMH)

As far as bananas plot twists go, it’s hard to think of what can top this memoir about a twisted family affair. When Brodeur is 14, her mother wakes her up one night to tell her she just kissed their family friend and to ask if she wouldn’t mind helping them facilitate an affair. The plot only thickens from there. This was the kind of immediately readable story that made me miss my subway stop, made all the more juicy by the fact that it’s all true. —T.O.

How We Fight for Our Lives by Saeed Jones (Simon & Schuster)

Full disclosure, Saeed Jones used to work at BuzzFeed News, so we’re biased. But his book really is good, an absorbing coming-of-age story about growing up young, black, and gay in Texas. —T.O.

In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado (Graywolf)

A formally innovative memoir about an under-covered subject — an abusive relationship between two women — Machado’s second book is a thought-provoking stunner and proof that the praise heaped on her for her debut short story collection Her Body and Other Parties, was well deserved. Writing in short discursive chapters, occasionally stopping to address some aspect of queer theory or list her favorite Disney villains, Machado weaves a captivating tale of a romance gone sour and the deep scars that emotional and verbal abuse can leave. —T.O.

Read our profile of Carmen here.

Homesick: A Memoir by Jennifer Croft (Unnamed Press)

Croft’s memoir is impressionistic and inventive — through brief, nonchronological chapters written in the third person (and giving her younger self a different name) she recounts a childhood derailed by her little sister’s terrifying seizure disorder. Interspersed among these chapters are Croft’s own photographs, connected by captions that read as one long, deeply loving letter to her sister. As a whole, Croft has created a near-perfect way to bring her childhood experience to life, mitigating her unavoidable alienation from the past with the distance of third-person narration, and exploring the shifting roles of language, empathy, and identity in her relationship with her sister. —A.R.

The World According to Fannie Davis: My Mother’s Life in the Detroit Numbers by Bridgett M. Davis (Little, Brown and Company)

An incredible story, Davis introduces us to her mother, a no-nonsense woman who grew up in the Jim Crow South and catapulted her burgeoning young family to middle-class wealth by running the numbers — the lottery operation that was banned for most of the 20th century until the US government realized there was money to be made in it. A source of indulgence, entertainment, and superstition for many working-class black families throughout the country, The World According to Fannie Davis offers a fascinating glimpse of how it all worked, set against the backdrop of a thriving Detroit and then a blighted one. —T.O.

Read an excerpt here.

Poetry

Library of Small Catastrophes by Alison C. Rollins (Copper Canyon Press)

Rollins' debut poetry collection probes the idea of the body as an archive — an accounting of tragedy and trauma, yes, but also of love and grace. Rollins explores the ways in which we store our personal and cultural histories and how they act upon us, in language so immediate and evocative it's sure to bring about some tears while reading. —A.R.

Magical Negro by Morgan Parker (Tin House)

From the trials and tribulations of dating white boys to imagining what Diana Ross was thinking in that famous photo where she licks her fingers after eating a pair of ribs, Parker’s third poetry collection is a beautiful ode to black womanhood in all its messy glory. Imbued with her signature wry humor and caustic honesty, it’s a reminder that Parker is one of the most exciting young poets working today. —T.O.

Read an excerpt here.

Lima :: Limón by Natalie Scenters-Zapico (Copper Canyon Press)

I felt like there was a moment in every poem within Scenters-Zapico’s sophomore collection that made me gasp from its sheer beauty. These poems meditate on all manner of borders — not only the literal boundary between the US and Mexico and the effects of those dueling places in the immigrant experience, but also the spaces between desire and sacrifice, sex and violence, masculinity and femininity. Scenters-Zapico's writing is lyrical, sensual, and often painful; it will linger in your brain for a long time. —A.R.

Arias by Sharon Olds (Knopf)

Olds has the goods in this eclectic collection of new verse, which runs the gamut from reflections on anal sex: “...If my mom had not beat me while I / clenched my butt as if to keep her out, / I might have liked the asshole more, I might / want to kiss it!” to the peculiar grief of meeting an ex-husband, “... and then / one went one way, / one another, / one in sheer relief, one / in grieving relief,” to Trayvon Martin. With its expansive range and warm honesty, this book shows us why the Pulitzer Prize winner is still among the most beloved poets alive. —T.O.

The Tradition by Jericho Brown (Copper Canyon Press)

In his latest collection, Brown tackles history and trauma both private and public, personal and narrative — especially blackness and anti-blackness, queerness and anti-queerness. Brown is experimental in format — often its playfulness acts in contrast to its heavy themes — and his rumination on desire, violence, loss, and faith is resonant. —A.R.

Feed by Tommy Pico (Tin House)

Pico concludes his “Teebs’ quartet,” or tetralogy if you want to get technical, with a final entry that still packs quite a wallop. Teebs, Pico’s alter ego, is on a book tour, at turns horny, hungry, and overwhelmed by the dystopic news. That Pico manages to pull this all off while reflecting on his Kumeyaay heritage and putting in all the food puns is a tribute to his considerable talent. —T.O.

1919 by Eve Ewing (Haymarket Books)

The Red Summer of 1919 saw brutal race riots in cities across the US; the most devastating was in Chicago, lasting eight days and resulting in 38 deaths and nearly 500 injuries. In her second poetry collection, Ewing grapples with this violent moment in history, drawing from a 1922 report by six white men and six black men meant to analyze the event, and expanding this examination through her own keen insight and evocative imagination. Ewing blends past, present, and future, imagining the stories of those who lived through the riot and beyond, and inquiring into its lasting consequences. —A.R. ●