“There are moments when the world we take for granted instantaneously changes,” Jon Mooallem writes in the opening pages of his 2020 book, This Is Chance!, “when reality is abruptly upended and the unimaginable overwhelms real life. We don’t walk around thinking about that instability, but we know it’s always there: at random and without warning, a kind of terrible magic can switch on and scramble our lives.”

Mooallem is talking about the Great Alaskan earthquake — a 9.2 magnitude quake that struck on March 27, 1964, decimated Anchorage, led to over 100 deaths, and remains the most powerful earthquake in US history — but when I read the book for the first time last March, the scene felt uncomfortably familiar. At the time, I was beginning to suspect we were on the brink of our own catastrophe. My husband and I had, fortuitously, just moved to a new apartment so we no longer had to share a bedroom with our 6-month-old son, but after just three days of figuring out my new commute we were told we should probably work from home. Out on walks to explore our new neighborhood, neighbors were starting to wear masks; stores were starting to close. Soon those daily walks ended, too. But it was early enough that I believed in the brevity of this newly named pandemic’s effects. We’d all stay at home for a couple of weeks, maybe a month or two, until we got a handle on the spread.

But then my husband’s salary was cut; soon after, mine was, too. We said goodbye to our nanny. We tried to find toilet paper. I sat on the floor of the shower and sobbed. You know how this story goes; you were there, too. We, like those at the epicenter of the 1964 quake, would soon find ourselves in a “jumbled and ruthlessly unpredictable world they did not recognize.”

I’ve returned to This Is Chance! a few times since last March. I interviewed Mooallem over text message, joking about the parallels between the book and our current bewildering reality, not yet realizing how far the destruction would reach. I wrote about the book for both our best of spring and end of year lists. For a while, I wouldn’t shut up about it to friends and acquaintances who, like me, were slowly losing the ability and will to read. And now, suddenly, it’s March of 2021. I’m putting together a list of new paperbacks, and there it is. I remember what it was like to read it for the first time, and I think, God, was I ever so young?

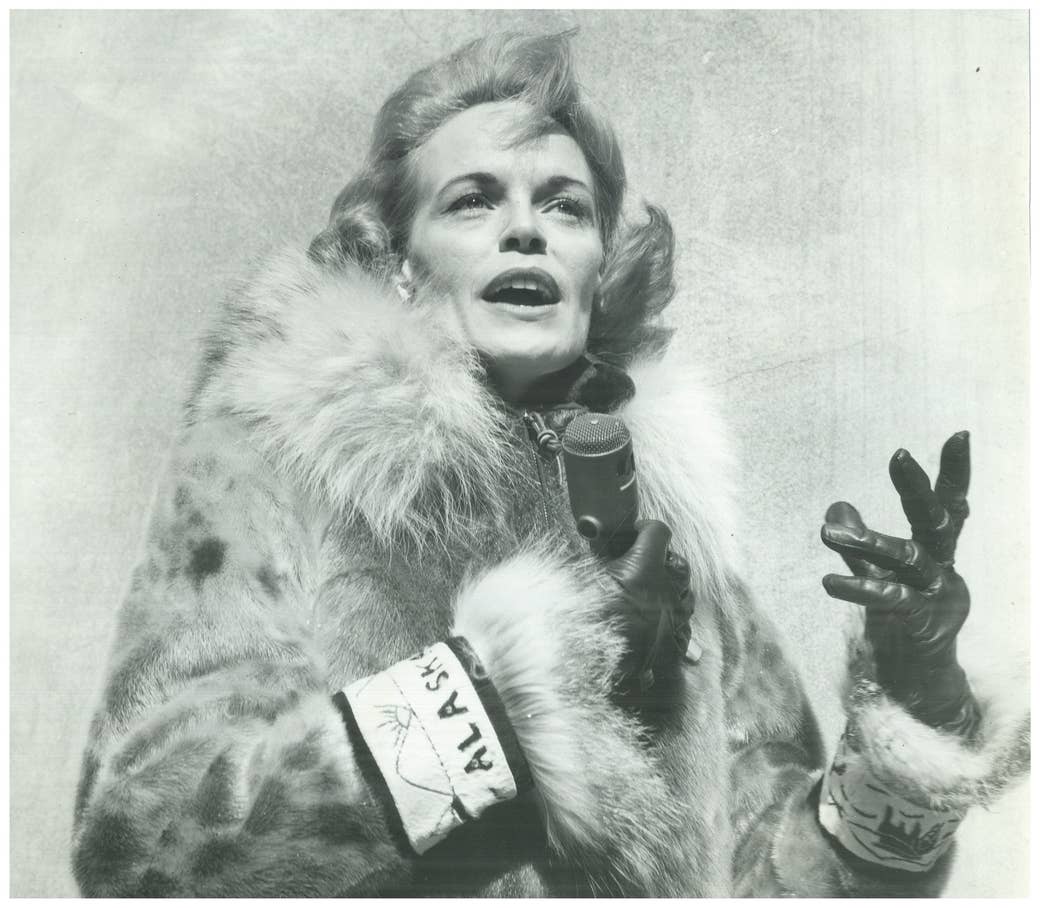

This Is Chance! is about Genie Chance, a broadcast journalist and mom — diligent but often underestimated, forced to placate the egos of her male colleagues and subjects (and husband) — who experienced what’s now known as the Great Alaskan earthquake while driving with her son. She dropped him off at home and immediately ran back out to investigate. Using her transistor radio, Chance started broadcasting from her car, and then set up a station at the Public Safety Building, which became an impromptu command center. She began not even an hour after that first quake, and continued for the next thirty.

Everything that happens in Anchorage over the course of the following three days passes through her; her story is the story of her city. Anchorage, which had been incorporated as a city just 44 years earlier, was unprepared; it “had no protocol for this kind of emergency.” Chance saw the chaos around her — felled buildings, crushed cars, split roads — and decided to claim the responsibility of preventing a possible “breakdown of civil society,” to “stave off that mayhem.”

Others followed suit. A public works employee spearheaded a campaign to map out the city’s destruction and hazards, deputizing a group of city employees and volunteers using DIY armbands — strips of white bedsheets with the word “police” handwritten in lipstick. Amateur ham radio operators became ad hoc messengers, “hunkering in their radio-equipped cars to function as a kind of substitute telephone system.” An assistant professor took the lead on “organizing a systematic effort to scour the city for those still missing and to collect the dead.” Not to mention the countless people digging through rubble on the street, pulling neighbors out of trapped cars, administering first aid. Recalling the response in the immediate aftermath, one resident said, “everybody tried to help […] Clerks, bookkeepers. Everybody was trying to do a little bit of everything for everybody.”

The city’s Civil Defense bureau was theoretically in charge of the emergency response, and the morning after the first 9.2 magnitude quake, Douglas Clure, who had recently resigned as the agency’s director, returned to the Public Safety Building to announce that it was taking control. But the office was a mess of “antic ineffectualness.” Those who’d been doing the agency’s job for almost a full day “found it was faster, and less frustrating, to bypass Clure [and] just solve the problem themselves. They complained that Clure’s people moved too slowly, or in circles. Clure seemed hamstrung by finicky questions of protocol. ‘Who’s going to give me this authority?’ one Disaster Control worker remembered him asking continually, whenever some unconventional emergency action was proposed.”

The earthquake revealed the fragility of the young city’s literal and figurative foundation. It also revealed its citizens’ strength. Facing a “complete breakdown of all bureaucracy,” the community improvised its own disaster management system, comprising “volunteers … ordinary citizens, many of whom seemed no more qualified to handle such a crisis than Genie was.” But handle it they did.

Anchorage’s government failed the city largely because at the time it was “still an excruciatingly young place.” Ours had no excuse. We’ve spent over a year being failed — by state and federal politicians voting against financial relief, botching lockdowns and vaccine distribution; by banks and landlords; by employers; and, yes, by some neighbors. But in the midst of the negligence of the systems ostensibly built to protect us, community formed around those looking to support and be supported by others. What else was there to do? People turned to mutual aid funds, crowdfunded support for small businesses, fought evictions, found and distributed PPE. If the pandemic has taught me anything, it’s that many of us survived not because of our governments, but in spite of them.

We can’t talk about This Is Chance! without talking about Our Town. Thornton Wilder’s 1938 meta play about small-town life, about the extraordinary masquerading as the ordinary and vice versa, drives Mooallem’s narrative. When the earthquake hit Anchorage, its small local theater was preparing for a production of the experimental work; in the midst of the destruction, a fallen banner reading “Our Town” lay in the rubble. It’s a detail that would read as too on-the-nose if this were fiction.

Our Town’s plot is uneventful and almost beside the point — in a small town called Grover’s Corners, two young neighbors fall in love, get married, grow old, and die. The star is the Stage Manager, a narrator with godlike omniscience who shoots into the future to describe each character’s whole life and eventual death, and zooms out to remind the audience how painfully insignificant a town and a life can seem when considered from a distance. Mooallem writes:

"The Stage Manager is saying: Remember us. Recognize us. It’s one community’s simple insistence that it mattered, made urgent by a suspicion that, ultimately, it might not matter. In other words, the overwhelming disaster everyone in Our Town is confronting is irrelevance: a creeping awareness that no matter how secure and central each of us feels within the stories of our own lives, we are, in reality, just specks of things, at the mercy of larger forces that can blot us out indifferently or by chance."

In This Is Chance!, Mooallem fills the role of the Stage Manager; by tracking those three days in Anchorage, hour by hour, he takes up the mantle of demanding these people, this town, be recognized, despite the inevitability and mundanity of disaster. In a year of universal grief and loneliness — when, so often and in so many ways, we were told our lives were expendable — this rings especially true.

What I realize now, revisiting the book, is that it didn’t stick with me because of its prescient portrayal of disaster — it was its unsentimental testimony of cooperation, its rejection of nihilism in the face of catastrophe upon catastrophe. When describing the Chance family’s refusal to separate after the earthquake, despite Genie’s parents’ insistence that she send the kids to their home in Texas, Mooallem writes, “Our force for counteracting chaos is connection.” It’s a sentiment that travels well. Nothing is unique in the grand scheme of things: how bleak, how beautiful. ●