Cheryl agreed to go to Las Vegas in a last-ditch effort to save her marriage.

She and her husband of nine years, Dan, had become chilly with each other, but he’d insisted on this vacation. She had hoped the trip would remind her why she’d fallen in love with Dan when she was just 22, and why she’d married him in Vegas four years later, in 2005, wearing a poofy white dress with her hair dyed pink and black to match her sneakers. Maybe revisiting the place would be romantic.

But under the glaring fluorescent lights, she saw instead how distant they’d become — she wanted to climb the Spring Mountains that rise up out of the Mojave Desert, and he just wanted to gamble at the Riviera. At a Vegas club, she watched as he spent $70 on a bucket of six Bud Lights; she’d stopped drinking in her twenties. When she wanted to get a pedicure, he criticized her one indulgence as a waste of money. But Cheryl, who at 35 had long deferred to him on financial decisions, got the $25 pedicure anyway. She’d always lived within her means, and this seemed like a reasonable splurge.

Months later, she asked for a divorce and began planning to transfer from community college to a four-year university. But when Cheryl, who needed student loans, opened the credit report she’d requested, her dreams of a new life collapsed.

She was sitting in her car outside the Austin grocery store where she worked part-time when she tore open the envelope and learned that she owed nearly $19,000 on credit cards she’d never known existed. Her soon-to-be ex-husband Dan had opened at least five in her name since 2006, just a year into their marriage. He’d been spending money she didn’t have. Cheryl, who earned about $12,000 a year, was solely responsible for paying off these cards. If she didn’t, her credit score would be ruined. Not only would she have no chance of getting a loan to go back to school, she’d be unable to get a mortgage, buy a new car, or crawl out of the mounting debt incurred from late-payment penalty fees on the cards.

She tore open the envelope and learned that she owed nearly $19,000 on credit cards she’d never known existed.

She later thought back to that Vegas trip. “He’s bitching about me spending $25 on a pedicure, and then I come to find out that it was my $25,” she said.

As long as they’d lived together, Cheryl had relied on her husband to handle the finances. It felt as if he was caring for her. Dan was 11 years older and, she thought, better with numbers than she was. In their time living together, he’d always fetched the mail each day from their mailbox, which seemed like a helpful household chore. She now thinks it was a way to make sure she never saw the bills.

When she discovered the fraud, “So many people kept telling me, ‘Oh, it doesn’t matter. Everybody’s in debt,’” said Cheryl, who asked that her last name be withheld. “Yeah, but I’m not. I’m not that person. I’ve lived my life intentionally so I’m not that person. And to wake up one day and find out that I am that person, and it’s not my choice? That’s not fair.”

She knew that if she didn’t call the cops, she’d be stuck with the credit card bills, so she picked up the phone in December 2015 and reported the theft to the Austin police.

Much of the institutional response to intimate partner abuse has focused on women experiencing physical violence. Financial abuse has rarely been a consideration, despite the fact that money itself is often a tool of abusers. Since the 1980s, scholars have repeatedly found that women stay in abusive relationships longer because they can’t afford the cost of leaving. They’ve also found that abusers use money to control their partners — from sabotaging their jobs to withholding rent money or cash.

And yet relatively few studies have looked at economic abuse, which is what Cheryl endured. The oversight extends to the law, which does almost nothing to protect victims of what has come to be known as “coerced debt.” The first study specifically looking at how mostly male abusive partners use debt to hurt their victims was published in 2012, by University of Texas at Austin law professor Angela Littwin. That study and subsequent research suggest that coerced debt is a common form of abuse. A forthcoming study by Littwin, Michigan State University psychology professor Adrienne Adams, and Michigan State PhD student McKenzie Javorka took data from 1,823 women who agreed to take a survey after calling into the National Domestic Violence Hotline. Their study, which was provided to BuzzFeed News and will be published in the journal Violence Against Women, found that 52% of the callers had experienced coerced debt.

Women in the study whose partners hid financial information from them, like Cheryl’s husband did, were more than three times as likely to be the victims of coerced debt.

Some abusers commit straightforward identity fraud, taking money or credit from a partner without their knowledge by pretending to be them via online applications or other means; some use violence or physical intimidation to force a partner to take out a loan or sign a lease. The damage to these victims’ credit can have an immediate impact on their lives, making it harder to get new housing, a new job, and a new life away from abuse.

The damage can have an immediate impact on their lives, making it harder to get new housing, a new job, and a new life away from abuse.

But proving that someone forced you to take out loans or credit cards without your consent is difficult, especially when two people are married or have merged their finances. State and federal laws say that identity theft happens without the victim’s knowledge. If a person consents to spending their own money — even if that consent is given under duress — it doesn’t qualify as identity theft in most of the US. Under most states’ laws, the assumption is that if someone knows their money is being spent, they cannot later claim to have been a victim of theft. An analysis by the public policy advocacy group Texas Appleseed found that only three states — New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Ohio — have a broader definition of identity theft that could protect people who were forced to consent to their money being spent.

And when one partner takes out credit cards in their spouse’s name, whether that spouse knows it or not, the credit card company is seen as an innocent third party who’s owed payment. That leaves people like Cheryl indebted, unless they can win in the arduous process of fighting creditors and credit bureaus.

Lisalyn Jacobs, an attorney and adviser at the Center for Survivor Agency and Justice who has worked on four different versions of the Violence Against Women Act, said that in the 2013 reauthorization process, economic abuse went unmentioned. The 2018 reauthorization of VAWA would have added economic abuse to the definitions of domestic violence, but Congress let it lapse.

As policymakers develop a more nuanced understanding of domestic violence and as consumer credit becomes easier to obtain, the problem is beginning to get more attention.

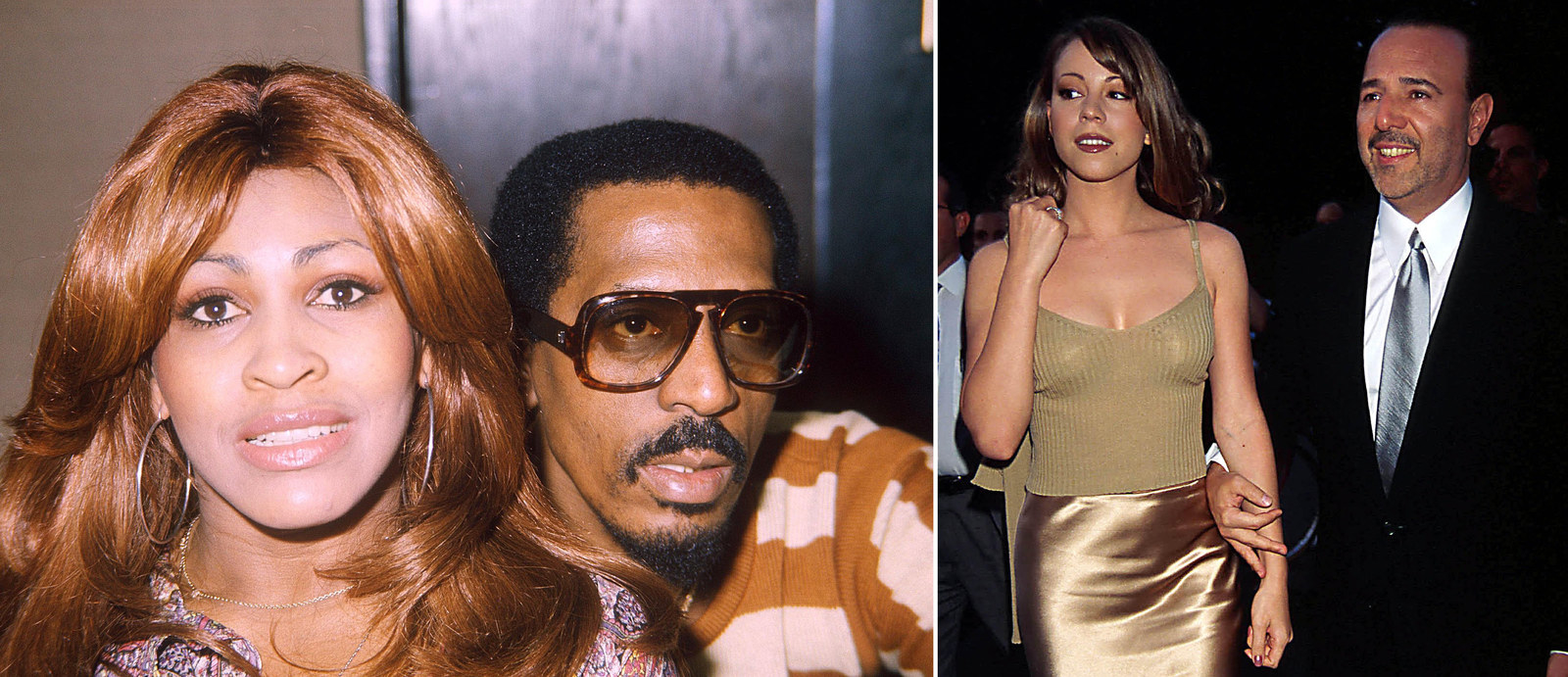

But in popular culture, economic abuse is often mentioned without being acknowledged: When Tina Turner fled her violent husband and music partner Ike, she wasn’t given access to their money, and ended up on food stamps. Mariah Carey has described her relationship with then–Sony Music chair Tommy Mottola as controlling and emotionally abusive, and in 2005, she told the Guardian that getting out of the marriage “was almost impossible” because he controlled her career, with “everybody being on his payroll.” In news stories, their financial dynamics were framed as incidental, not as a form of control in itself. The 2017 podcast Dirty John discussed at length how the titular character stole money from his wife and threatened to financially ruin her, yet he was depicted as an exceptional scammer rather than a man who commits economic abuse.

Littwin, the law professor who coined the term “coerced debt,” essentially stumbled upon it while working on a larger study of bankruptcy. She found a link between relationship violence and bankruptcy — women filing for bankruptcy were much more likely to have experienced abuse than the general population. She’d hypothesized that domestic violence was costly and led to bankruptcy. She also thought that bankruptcy caused stress, and stress increased violence. But when she talked to domestic violence advocates and attorneys, they told her the opposite was true: Men who were already abusive were causing bankruptcies by driving their partners into debt through underhanded means.

The advocates told Littwin they had worked with women who discovered fraudulent credit cards in their name, and women who were forced to take out loans for their husbands or boyfriends. One attorney she interviewed was a domestic violence survivor herself. “She found out about coerced debt in her name when she went to apply for student loans for law school,” Littwin said.

One woman’s violent boyfriend, unbeknownst to her, listed her as the sole lessor of a Ford Fusion. “She couldn’t drive.”

Under existing federal law, there are some solutions that can help survivors repair credit damaged by their partner without having to pay off the debts. But because intimate partner identity theft isn’t accounted for in the laws, most of the solutions are creative workarounds that aren’t specifically focused on victims of abuse and coercion.

Divya Subrahmanyam, who works on consumer debt cases for low-income New Yorkers with CAMBA Legal Services, recalled a case in which a woman’s violent boyfriend took her to a car dealership and, unbeknownst to her, listed her as the sole lessor of a Ford Fusion. “She couldn’t drive,” Subrahmanyam said. The woman, an immigrant from Haiti who did not speak much English, couldn’t even read the contract that her boyfriend had her sign.

Subrahmanyam ultimately got her client released from the debt not because of the fraud and abuse, but on a technicality related to leasing motor vehicles. There’s no specific law she can point to that says a person who is forced into a debt should not be responsible for paying the creditor, so she pursues other arguments for her clients. As far as she knows, a judge has never ruled in favor of a victim in a consumer credit case purely because they were forced into a debt.

And as a woman gets a debt forgiven, she also has to fix her credit report. Under the Fair Credit Reporting Act, a victim of fraud can submit law enforcement documentation — typically a police report — to credit reporting agencies. The agencies must then block or remove the accounts from her credit report. But even if victims are willing to turn to the criminal justice system, police sometimes refuse to take a report of intimate partner identity theft.

Carla Sanchez-Adams, the attorney at Texas RioGrande Legal Aid who eventually helped Cheryl, struggles with dismissiveness from law enforcement in Texas. Subrahmanyam said the same of New York: “There’s both confusion about what’s allowed within the context of a marriage or a domestic partnership, and a skepticism of domestic violence survivors in general.” When money is involved, people who are already predisposed to think that women lie about domestic violence may assume these victims are lying to get out of paying a debt, she said.

The Austin Police Department did take Cheryl’s report. It was a surprisingly brief phone conversation, she said, during which Cheryl recalls being asked for only the most basic information. When she got off the phone, “I felt like nobody gave a shit,” she said. “I felt like, okay, you took my information. Are you gonna do anything with it?” When she called one month later to check on the investigation, her hunch was confirmed. The case was cleared because, as an officer had written in all caps in the report, Cheryl and the man who took out credit cards in her name were MARRIED. The police report noted that the district attorney’s office generally declined to prosecute cases like Cheryl’s, when the people involved were “financially entangled” through marriage or “any other relationship.”

The case was cleared because, as an officer had written in all caps in the report, Cheryl and the man who took out credit cards in her name were MARRIED.

She was devastated. “That deflated so much of my ability to feel like I had a voice, and like I had something that was even worth fighting for. I was ready to just give up and roll over and play dead by that point,” she said. Her ex had been promoted at a large technology company while they were still together, and she had quit her job at an insurance company to take more community college classes. In a hypothetical legal battle, he’d have far more resources. “This is a man that’s making almost $70,000 a year, and I’m barely at $12,000 a year. How am I gonna fight that?”

And as Cheryl found out, once you get the police report, getting the accounts and charges removed is harder than opening up a credit card online with your wife’s Social Security number. She tried multiple times on her own to tell the creditors these debts were the result of fraud, to no avail. When she first began calling the creditors, they told her she didn’t have enough information about the accounts, like PINs or their monthly mortgage payment, to prove that she was Cheryl.

There were, she said, “literally hours and hours of sitting on hold trying to talk to people, to get information.” People on the other end of the line kept transferring her to other departments, and no one seemed to be able to help her. “It’s almost like they intentionally try to see how many times they can pass you off to somebody else, just to see if they can frustrate you enough to where you give up,” she said. “I am stubborn as hell. Go fuck yourself, I’ve got time.”

She made no progress on her own. Ultimately, it took two rounds of disputes with the help of Sanchez-Adams just to get her credit report cleaned up. They began disputing her credit report together in August 2016, and she didn’t get an accurate one until more than a year later, in November 2017. “I could go on and on and on about how many lawsuits are filed against the major credit reporting agencies,” Sanchez-Adams said. “They’re supposed to have reasonable procedures in place to ensure maximum possible accuracy. They don’t.”

She listed federal laws she often sees creditors violating: They don’t respond to disputes within the 30-day window required by law; they don’t inform you of the results of the internal investigation required by law within 90 days; they don’t have a clear system for reporting billing mistakes. Cheryl and Sanchez-Adams once spent two hours on the phone being transferred back and forth between a creditor’s departments, when all they wanted was “to confirm with the billing errors department that they got our freaking letter,” Sanchez-Adams said. The attorney had sent the same letter disputing Cheryl’s account to six different addresses because it was unclear which one led to the proper department, a lack of clarity that is against federal law. For another card, she and Cheryl eventually filed a lawsuit against the creditor, court records show. It ended in the spring of 2018.

“This is a man that’s making almost $70,000 a year, and I’m barely at $12,000 a year. How am I gonna fight that?”

Cheryl’s debt never landed with a collections agency; she learned about it relatively early; and she came from a middle-class background and had a family able to help support her. She didn’t take out her own loan to pay off the debt, like some women do. She eventually escaped the financial nightmare her ex-husband created — but it took her a full two years after her divorce to get all the fraudulent debts settled or canceled.

And the abusers generally face no repercussions for the fraud they perpetrate. Sanchez-Adams, who’s worked on hundreds of cases like Cheryl’s over nine years, said she’s never seen a perpetrator prosecuted for identity theft. Cheryl’s ex-husband generated debt in her name, and then left her to fix it alone.

In retrospect, Cheryl wishes she had met Sanchez-Adams sooner and sued her ex for the money. But at the time of the divorce, “I was scared of him, and not being able to get the divorce, and having him be able to screw me over one way or another,” she said, noting that he made around six times as much money as she did. They have no contact now.

Cheryl has gone back to college to pursue a degree in psychology, and for that she’s taken out student loans. Now that she’s set up a fraud alert, she refuses to look at her credit score, because, she said, all it ever did for her was “make my life fucking hell.”

She doesn’t have any credit cards. ●

This story is part of a series about debts of all kinds.