Born seven weeks premature with failing lungs and a hole in his heart, my 10-day-old son lay in an incubator in neonatal intensive care, tiny earmuffs over his ears to protect him from unexpected noises: the snap as the nurses shut three-ring binders; the muffled crying of another mother from behind the mobile privacy curtain; the beeping alarms, including his own, that went off whenever a baby’s breathing stopped or a heart failed to pump adequately.

What the earmuffs couldn’t protect him from was my guilt. If I hadn't ignored the warning signs, if my primary doctor had paid attention to my symptoms, he might not have needed an incubator at all.

I was 33 weeks pregnant when I came down with HELLP syndrome, a little-known and often fatal pregnancy-related illness. What started as a stomachache had turned into stabbing abdominal pain so unrelenting that I had eaten barely anything in five days. Three days after the abdominal pain started, my primary physician misread blood results and diagnosed me with gallbladder disease. But after listening to me say, “I’m sure it’s just food poisoning” for several sleepless nights, my husband finally insisted on driving to the birthing center where my obstetrician was on call. When I told her about the more minor lower abdominal cramps accompanying the severe pain, she raised her eyebrows from the paper containing my blood work results.

“That’s because you’re in labor,” she said. “Those are contractions.” I liked this woman, my favorite in my OB practice, and I liked her even more for the edge of "Are you a complete idiot?" that overlaid her words.

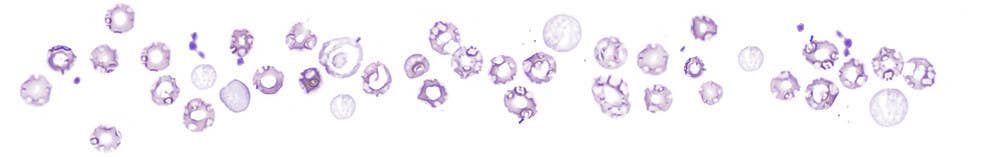

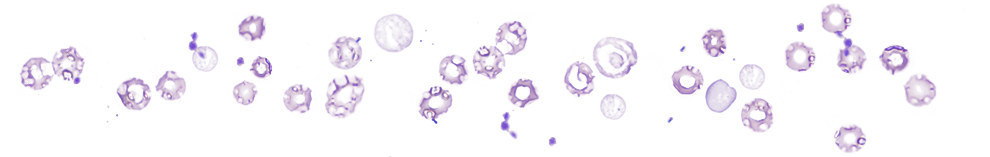

“You have HELLP syndrome,” she said. She explained the acronym: hemolytic anemia, or hemolysis (the H), elevated liver enzymes (EL), lowered platelets (LP). “It’s rare,” she said. “It’s caused by pregnancy, we don’t know how, and the only treatment is delivery.” My platelet levels were so low (down to 26,000 per microliter from a normal range of 150,000–450,000) that we would have to deliver that day.

I remembered skimming over the short paragraph on HELLP in the “Serious Complications” section of my What to Expect book but hadn’t paid much attention to it. I was 32 and healthy. Nobody in my extended family had ever had a problem with pregnancy or childbirth. Pregnancy was natural, all my friends said. Pioneer women hadn’t used painkillers. Women have been giving birth to healthy babies for thousands of years without the help of doctors.

Part of me scoffed at these statements, which neglected the inconvenient truth that women have also been dying in childbirth for thousands of years. But part of me agreed with them. After all, my own ancestors were pioneers and peasants who’d carried their babies to term in the middle of nowhere. Surely those “Serious Complications” would never apply to me.

Why else would I have sat on the couch for days, squirming in pain, unable to read, unable to eat, barely able to sleep, 33 weeks pregnant, and not called my obstetrician?

She told me my liver was failing and that I’d lost too many platelets for a normal delivery. It would have to be a Cesarean. “And I’m afraid,” she said, “that you’ll have to go under full anesthesia. You’ll lose too much blood because it doesn’t have enough platelets to clot. I’m sorry,” she added. I didn’t have time to be sorry. I started fading fast, my speech a little slow, my mind more so.

Any attraction I’d ever had to my friends’ natural and homebirth advocacy gave way to relief that I wasn’t one of my own pioneer ancestors. The wood-paneled birthing center took up the fifth floor of a conventional hospital, and we needed all the modern medicine we could get. An IV trolley rolled in and transferred platelets into my floundering bloodstream. My husband and I talked to the medical staff who came in as if words and our habitual friendliness could keep panic at bay, while our eyes twitched nervously every time the blood pressure machine beeped or another IV went into my wrist. He stroked my head and I asked him to stop. My skin crawled with restless irritation.

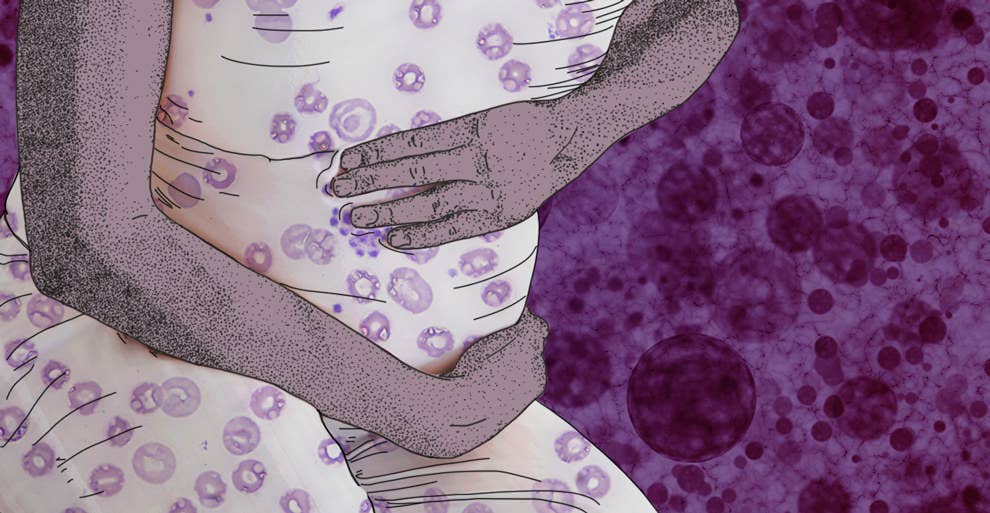

The medical terminology used to describe HELLP syndrome only highlights the viciousness of the illness. There’s no way to sugarcoat it: The capillaries freeze up, and the blood platelets crash into suddenly hard walls, breaking into useless little pieces. The liver becomes overloaded with the waste and works overtime, laboring like an out-of-shape office worker suddenly asked to run the Boston Marathon.

HELLP syndrome’s maternal death rate can range from 1–25%, the variation being chalked up to the fact that misdiagnosis is extremely common. Part of the fault for this lies in HELLP’s rarity, part in the vague understanding researchers have of its causes and pathology, and part in its ability to mimic both regular pregnancy symptoms (nose bleeds, slightly high blood pressure, nausea, discomfort) and several nonlethal illnesses, like the flu or gallbladder disease.

When caught early, HELLP can be stabilized just long enough to give a baby’s most late-developed and fragile organs — its lungs — more time to grow. My son’s lungs got as many steroids as they could pump into me before delivery, but he didn’t get that luxury of a little extra time. If they didn’t take him out, my OB said flatly, I would die. She gave John the best chance she could while saving my life.

Our story is one of the lucky ones. John was finally discharged after a month in neonatal intensive care, and, after weeks of painful struggle and a relationship with a breast pump I’d learned to hate, he even breast-fed enthusiastically and grew squishable baby fat.

I try not to get lost in the might-have-beens, both the good and the bad, even though sometimes the memory of those days and nights sitting in the beeping NICU leaves me short of breath, smothered under guilt I’m not even sure I deserve. At those times, I wish a fluffy pair of earmuffs could shut out the internal voices that like to remind me of what could have happened, what I and everyone else should have done. I should have called my OB as soon as the abdominal pain started. The primary physician should have paid closer attention to my platelet levels and liver enzymes. I should have noted the symptoms of all those “Serious Complications” and watched for them.

Sometimes I have to force myself to look back and say: I did the best I could with what I knew at the time. Because it’s hard to forgive myself for believing lines about pioneer women bearing babies in midwinter, even though I’m well aware of what their dismal survival statistics were, for pushing through the abdominal pain and not insisting on seeing my obstetrician when I now know that my son and I were tottering toward death. But like everything related to parenting — to life — the only choice I have is to learn what I can from the lesson I had.

Three weeks ago I sent my son off to first grade with a hug and kiss, overwhelmed with gratitude as I watched his Ninjago backpack bouncing across the schoolyard.