In 2007 I met a woman named Donella Wilson.

She was born on May 24, 1909, on the Peterkin plantation in Fort Motte, South Carolina, the granddaughter of enslaved people. She taught herself to read and write by lamplight, going on to graduate from Allen University and become a teacher. She helped raise and teach at least three generations of my family on the Lang Syne Plantation in Fort Motte.

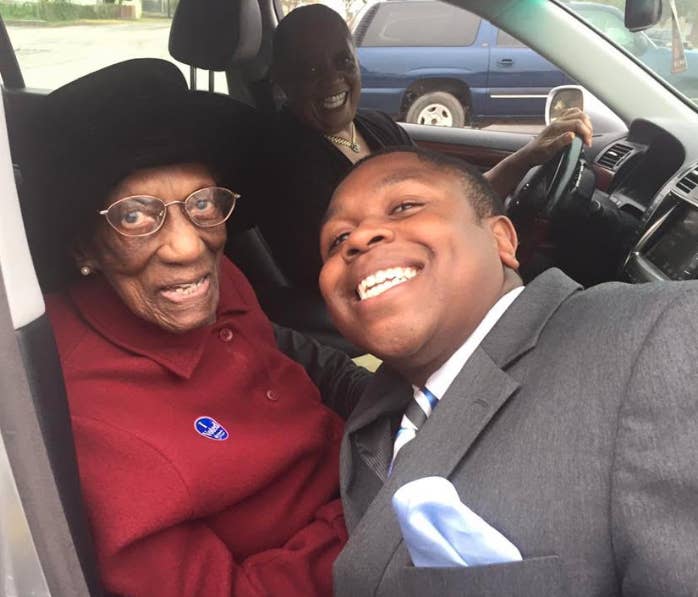

Wilson was a woman of remarkable strength and grace, but one of her many accomplishments always stood out to me. She had voted in every single election — primary and general — since 1947, in a streak that only ended with her death in 2018 at the age of 108.

Twice we went together to vote for Barack Obama, the first black president of the United States. Twice we voted together for Steve Benjamin, the first black mayor of Columbia, South Carolina. And the last time we voted together, we voted for the first woman candidate from either major party, Hillary Clinton.

But to understand Donella Wilson’s story, we must also understand a man named George Elmore. He was born in Holly Hill, South Carolina, in 1905 — roughly 40 years after the end of the Civil War and less than 10 years after Sen. “Pitchfork” Ben Tillman and his allies rewrote our state constitution to codify school segregation and the disenfranchisement of black voters. Elmore grew up in a state entrenched in the Jim Crow era.

But he imagined a different world and moved to Columbia, where he got to work opening business after business while moonlighting as a taxi driver and photographer. He was personally successful and comparatively wealthy — which is why it was a little surprising when in 1946 he walked into a small grocery store in Columbia’s ninth ward and tried to register to vote.

Back then, South Carolina and states like it across the South used a closed-party system as one of the chief methods of denying black citizens the right to vote. And it worked because the only election that mattered in the Solid South in those days was the Democratic primary. If you didn’t vote in the Democratic primary, your vote didn’t matter.

But you had to be registered with the party to vote in the primary. And the party wouldn’t let you register if you were black. That’s how the powerful in South Carolina managed to circumvent the 15th Amendment while still denying folks who looked like me the right to vote — and it worked, right up until George Elmore walked into that grocery store.

Elmore had a very fair complexion. And while he had never used the lightness of his skin to pass as white, the clerk who took his voter registration paperwork never asked the question. And just like that, George Elmore registered to vote.

Actually casting his vote was another matter. In short: He tried, they denied, he sued, and he won. “It is time to fall in step with the other states and to adopt the American way of conducting elections,” District Judge Waties Waring wrote in his 1947 ruling in Elmore v. Rice, which not only affirmed Elmore’s right to vote but struck down South Carolina’s closed primary system.

It was a huge win for civil rights, but it wasn’t without its costs. The backlash from the lawsuit and the resulting decision cost George Elmore everything. He lost his businesses and was ruined financially. The never-ending threats and burning crosses caused his wife to have an emotional breakdown, which left her institutionalized for the rest of her life. He died in 1959, a pauper and broken man, six years before President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act.

Elmore’s sacrifices are one reason why black voters are likely to make up at least 61% of the total votes cast in South Carolina’s Democratic presidential primary next February. That strength didn’t happen overnight — and it didn’t happen by accident.

Since 1992, no candidate has won the Democratic nomination for president without winning a majority of the black vote. And since 1992, the winner of the South Carolina Democratic primary has gone on to win the nomination — with one exception. In 2004, “native son” John Edwards’ personal connections to the state drove him to victory here. He ended up with the VP nomination.

So don’t kid yourself — as Jesse Jackson once said, the hands that once picked cotton now pick presidents.

In the coming months you’ll hear a lot about the South Carolina primary, its importance, and the black vote in the state. But never forget the tremendous sacrifice that got us here. So many people gave everything they had — we know some of their names, and others have been lost to us forever. But the sacrifice remains.

We can talk about Sarah Mae Flemming, who was thrown from a city bus in downtown Columbia 17 months before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat in Montgomery. Or we can talk about Harry and Eliza Briggs, a gas station attendant and domestic worker from Summerton, South Carolina, who filed a lawsuit against the Clarendon County School District because the superintendent refused to provide even one bus for the black students who had to walk as far as 18 miles to and from school each day. And we could talk about how that lawsuit became the cornerstone of Brown v. Board of Education.

I think about Donella Wilson, unbowed and unafraid. Her memory reminds me that our strength didn’t happen overnight; it didn’t happen by accident, and it didn’t come without a cost. Our strength is fed from deep roots cutting through the Southern clay — we cannot be bypassed, and we will not be moved. You can ignore and discount us, but you cannot win without us.

Antjuan Seawright is a Democratic political strategist, founder and CEO of Blueprint Strategy, and a CBS News political contributor.