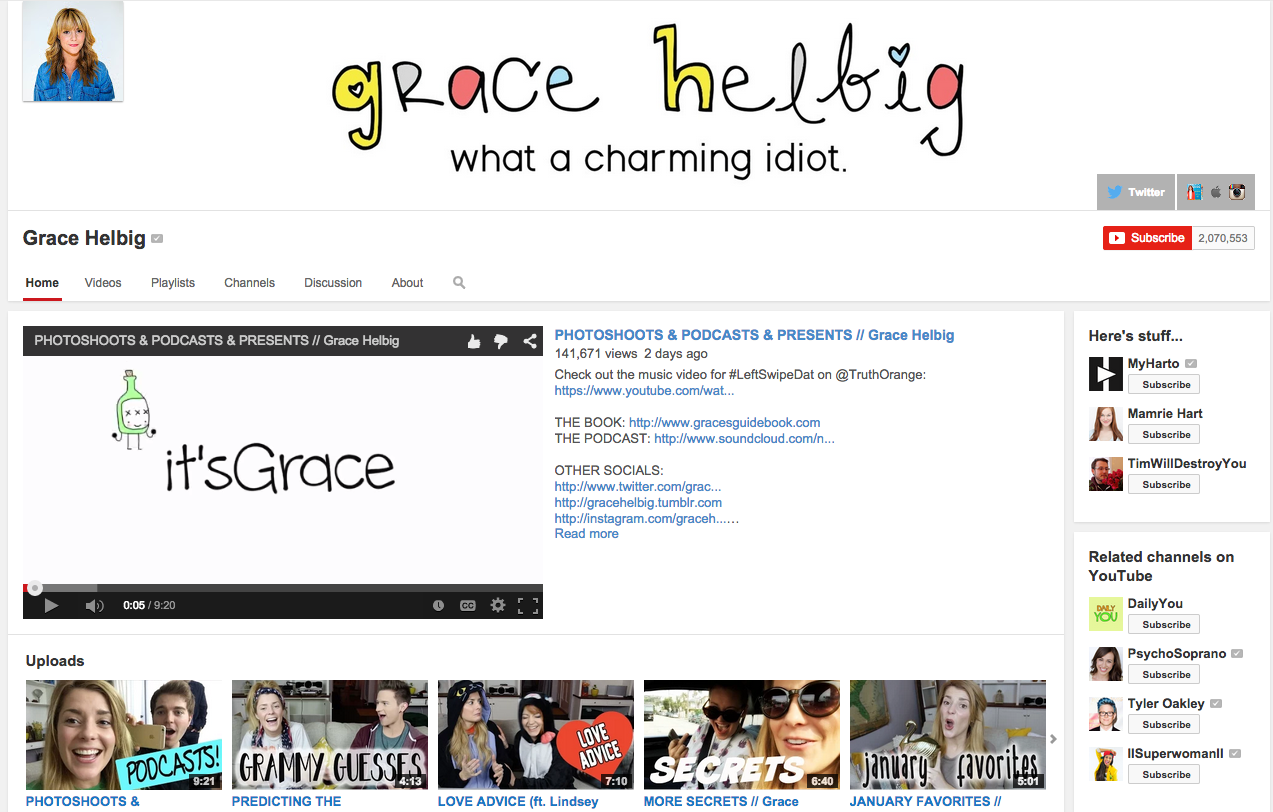

If you know a teenage girl, chances are she knows about Grace Helbig. With over two million subscribers to her YouTube channel, Helbig is one of the new class of YouTube superstars whose fame has been slowly, and then all at once, spread into the mainstream. Helbig has a book, a movie, and, starting sometime this Spring, a talkshow on E!. Why, then, have many adults never even heard her name?

The first time I saw a video of Grace Helbig I made a snap judgment: Look at this cool girl. Helbig wore an unremarkable striped T-shirt; her subtle cat-eye makeup was perfect. She had gorgeous skin and that sort of perfectly wavy hair that somehow looks like she just rolled out of bed yet still looks immaculate. So casual, yet undoubtedly calculated.

And this gorgeous girl was staring straight into the camera and telling me about almost pooping her pants on her way home from Target.

Classic Cool Girl: so chill, OK with farting around boyfriends, down to chug a beer, never nagging, the opposite of high-maintenance, the ideal girlfriend...or at least very skilled at performing all of those things in order to seem like the ideal girlfriend.

But as I immersed myself in the sprawling, multimodal world of Grace, I came to a crucial realization: She might seem like a Cool Girl, but it’s a variation wholly absent of the need to attract men. All of her Cool Girl components — her foul mouth, her willingness to talk about bodily functions, her general unruliness, and even her beauty — are never wielded to turn her into a sex object. She might have a great body, but that great body is hidden under what often seems like sleepover clothes, often paired with the sort of weird high ponytail you wear when no one’s around.

The astonishing and frankly refreshing thing about Helbig, who is 29, is the almost total absence of the pursuit of men from her phalanx of web videos, podcasts, Snapchats, and Vines that attract millions of viewers, most of whom are teens. Grace’s world is characterized not by looking hot for dudes, but being weird with girlfriends, both real (friends that show up in videos) and theoretical (you, girl watching the video). When she rates the “sexiest men on the internet,” it’s a farce; when guys do show up, they’re figured not as lust objects, but honorary sleepover guests.

Instead of identity predicated on the opinions and desires of men, Helbig is all about making the labor of femininity, and even friendship, visible. She calls herself the internet’s “awkward older sister” and “BFF,” but she’s also a different type of idol, one whose values and priorities are in stark contrast those proffered by teen idol factories like Disney and Nickelodeon.

Her humor isn’t “for me” — a phrase I heard echoed repeatedly when I asked others my age about their opinion of Helbig. But as a thirtysomething, it’s not meant to be: Helbig’s comedy isn’t rooted in irony or satire; it doesn’t belong on IFC after Portlandia. And yet, it somehow manages to feel far less pedantic than the laugh track, over-acting, and obvious gags that compose most teen-directed fare.

In a certain corner of YouTube world (read: the part where people make money), Helbig is ubiquitous. She tapes herself as she sits in a bathroom waiting for the train, dyes her hair, wakes up jet-lagged, and dorks around her hotel room. She tapes and produces videos at a grueling clip — three to five times a week — and pops up in the videos of dozens of fellow YouTube stars, as they pop up in hers.

Helbig’s brand of stardom threatens to demolish the untouchable aura that’s distinguished stars (think Angelina Jolie) for more than a century, but she’s setting forth an alternate — and, I’d argue, wholly feminist — model for the millions of young women who follow her.

It’s not that Helbig is offering a different “type” of celebrity so much as an entirely different mode of stardom. Her novelty is rooted in the specifics of her YouTube stardom and attendant technological and ideological shifts in the way that stars are made and consumed.

Since the days of silent cinema, film stardom has been characterized by its aura of distance, achieved by the actual size of the stars’ faces in close-up on the theater screen, tales of their extravagant and glamorous personal lives, and their overarching superlativeness. The spread of television in the late ‘40s and ‘50s sparked a sea change: The appeal of television stars was rooted in the feeling of immediacy (most of early television was filmed was broadcast live), intimacy (these stars were in your living room), and authenticity (none of the close-ups and polish that attended massive Hollywood productions).

The bulk of contemporary programming, from reality television to Oprah, still relies on the same principles of intimacy and authenticity, albeit in slightly different forms. They’re what addicts audiences to Keeping Up With the Kardashians and fostered the cult of Oprah. They’re both scripted, but their production of realness — like you’re part of the family, or privy to Oprah’s inner life — is irresistible.

YouTube stardom takes that same intimacy and authenticity and magnifies it. Television’s intimacy is the product of filming on sets dressed to look like living rooms and projecting into the home; YouTube’s intimacy comes from shooting in the home, often in what tech writer Paul Ford calls “The American Room,” and streaming on your computer or phone screen. When I finished watching a Helbig video the other day before getting on the subway, I felt like I was putting a very little Grace in my pocket.

The webcam, via which so many YouTube videos are shot, produces a lo-fi, generally unflattering aesthetic, especially when the subject films in a room that’s poorly lit. The closer the subject gets the computer — in anger, in excitement — the more you can hear the crackle of his breath, the pimple-scarred topography of his face. Watching a YouTube video doesn’t feel like watching produced entertainment; it feels like Skyping.

Even when a star like Helbig gets better equipment and training, he or she often sticks to the aesthetics that govern the lo-fi video. The goal, after all, isn’t to look like television; it’s to look like a YouTube video, only better. Better-lit, better edited, better scripted, but still with the feeling of spontaneity, DIY, and I-did-this-in-my-bedroom that defines the medium.

Those aesthetics of intimacy contribute to the feeling of authenticity: The more lo-fi the production seems — the less mediated — the easier it is to believe that you are accessing the “real” star. It seems like the star is always taping him or herself, which, by extension, suggests that there’s no one else in the room: no one directing, no one telling the subject to do another take.

There’s just raw, seemingly unfiltered access — an aura maintained, despite the clear evidence of edits, by preserving bloopers, adding outtakes, and unabashed revelry in on-tape fuck-ups. One of the hallmarks of Helbig’s recent videos is her sloppy muting of profanities; her editing, generally speaking, can best be described as that of a 12-year-old, replete with gratuitous slo-mos, sound effects, filters, and loops.

Authenticity and intimacy are always bolstered through the multimedia requirements of YouTube stardom — what technology scholar Liz Ellcessor calls “a star text of connection.” This “connection,” however, is more than the frenzied cross-promotion that places stars in one another’s projects (and, as a result, expands their audiences). Because while YouTube was the birthplace of most of these stars, they’ve expanded their rule to nearly a dozen content streams: In addition to maintaining a YouTube channel, Helbig hosts a podcast, produced and starred in a straight-to-internet film (Camp Takota), wrote a New York Times best-selling book (Grace’s Guide: The Art of Pretending to Be a Grown-Up), sells out national tours, appears at conventions like Vidcon, maintains active accounts on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, Tumblr, and Snapchat, and will begin hosting her own E! talk show in the spring.

The core of Helbig’s friend world is the “Holy Trinity,” composed of Helbig, queer vlogger Hannah Hart, and mixologist Mamrie Hart. (The two aren’t related, but the same last name amplifies the feel of sisterhood). They make regular cameos on one another’s YouTube channels and Instagram feeds; together, they produced Camp Takota, a 95-minute meditation on the value of all-girls camp, and documented the three-week shooting process extensively.

Videos of the three have a unique blend of sometimes zany, sometimes deadpan humor that feels exactly like the type of video you might have made with your best friends at 16. There’s an inherent confidence — all YouTubers have some form of it — but it’s mixed with heavy self-deprecation, improvisation, and fits of giggles. They feel preternaturally at ease with other and the camera; they manage to dance like no one watching even though everyone is watching.

The life of the Holy Trinity feels like the very best of sleepovers, punctuated with weird food projects, makeup experiments, watching movies, and overwrought impressions of themselves and others. That the vast majority of their videos are shot in their kitchens and living rooms only contributes to the feeling of a discreet space where you can be a weirdo with your friends. Their humor isn’t juvenile so much as physical: They’re masters of the reaction shot much in the way Lucille Ball was.

Ball’s most famous skit is “Vitameatavegamin,” in which she does successive takes of a cough syrup commercial as she gets increasingly drunk. But it’s drunkenness the way children imagine drunkenness — immediate and hilarious. That’s exactly how “Drunk Kitchen” works: The three have beers in hand, but manifest “drunkenness” much in the way that a teenager does after one beer, when the beer is simply a pass to act weirder, louder, freer.

Which isn’t to suggest that the real Grace, Hannah, and Mamrie don’t drink: I’m sure they do. It’s more that their performance of drinking, like their performance of cooking or makeovers, is all in the service of hanging out together. And that hanging out isn’t about gossiping, or being on their phones, or even talking about boys. It’s a distorted idea of what adulthood looks like — the only people I know whose lives feel like sleepovers are new parents, only those sleepovers lack all of the fun — but Helbig’s shtick isn’t to suggest what her teen viewers will be, but what, in their own lives, they could be: introspective, brave, anchored by friendship, living a life that’s not defined by romance and the desires of others.

In interviews, in her book, and in her videos, Helbig talks constantly about her introversion. That introversion was the catalyst for her first set of videos — which she shot while house-sitting for a friend — but also serve as a point of identification for her fans. It’s not that an introvert doesn’t want friends, or intimacy, after all, it’s that she wants it in particular settings and in particular doses. Helbig might seem like she’s having a nonstop sleepover, but the bulk of her time is spent by herself: filming her solo videos, editing them, and interacting with fans.

Social media is, in truth, an introvert’s dream: a way to feel connected while being alone. That’s not antisocial; it’s nurturing. I get it; I do myself. When I was a teen, I would’ve loved someone like Grace telling me that it’s OK to feel exhausted by the work of publicly performing femininity, and even more OK to enjoy hanging out, alone, in your comfy pants.

Some of Helbig’s fans may be legitimately sad in their loneliness. But I would guess that the majority of them connect with her openness about the real-life negotiations of introversion, recognizing the ways it can liberate and soothe. I developed my skill as a writer and my curiosity as a thinker not by hanging out with other people, after all, but by reading and writing and exploring the early internet alone. Not everyone learns and grows that way, but a large, often unheralded percent do.

That’s the primary point of identification. But even if you’re not an introvert, Helbig’s personality and image is blank enough for most teens to map their desires onto her. Indeed, there’s something about her lanky body and dewy face that feels distinctly teen, despite her 29 years. She grew up with middle-class parents; she was the middle child; she went to a normal South Jersey high school and an indistinctive small public liberal arts college.

There’s very little, in other words, to block fans from identifying with her. Save, of course, her whiteness. And straightness. And it should be said that the vast majority of Helbig’s visible fans — on Twitter, Facebook, and other social media streams — present as white; the “way of being” she’s providing for young women is predicated on the privilege of whiteness, straightness, and straight up middle-classness.

The popularity of Helbig’s book, movie, and television show don't change the primary engine of her fame: her interactions with teen girls. Because if television fame is predicated on familiarity, internet fame spreads through interaction and accessibility. There's the interaction among Helbig’s fans, of course, but stars have always had fan groups. What distinguishes Helbig and other YouTube stars is the sheer extent of their accessibility. She regularly hosts Q&As on her Facebook page; she constantly answers reader questions in her videos; she posts entire videos showcasing the fanfic and art inspired by her and Hannah Hart. She talks back on Twitter. She poses for countless selfies with readers, who then make those selfies their Twitter avatars, like hundreds of visual testimonies to her accessibility.

Jennifer Lawrence might seem like a total down-to-earth girl and you may feel like you know all about Kim Kardashian’s waxing routines, but this is a totally different level of perceived intimacy. You don’t just feel like you know Grace; through hundreds of hours of footage and text, you know Grace. Similar to reality stars, there’s no differentiation between “performing Grace” and “personal life” Grace: Her talent is being herself, which, in turn, makes every corner of that self marketable.

Of course, access is not the same as knowledge. Helbig has spoken publicly about her desire to separate her personal life (her boyfriend, her family) from her online life. She calls her vlogger self as “myself heightened.” Fans don’t know everything about “the real Grace” so much as know everything about the segment of Grace that’s offered for public consumption. It’s a testament to her charisma, then, that audiences never sense that disparity.

This type of intimacy and authenticity characterize all of the successful YouTube stars. What distinguishes Helbig, then, is the way in which her image combines the revelry and joyful silliness of friendship with the quirk and self-reflection of the introvert. It might seem contradictory that an introvert would spend so much time recording her life for others to consume, but that contradiction mirrors the push-and-pull of so many teens’ engagement with the world: the simultaneous desire to connect and feel understood while still testing out your identity in private and safety.

Even Helbig’s videos that focus on putting on makeup somehow manage to send a message of femininity as a dress-up, an everlasting process of becoming than a static standard to which viewers should aspire. Given the sheer volume of content, it’s hard to fit any YouTube star into a precise “type”: They defy circumscription. Helbig may be zany and teen-like, but she can also be sincere and profound, confident and vulnerable, made-up and makeup-less.

Most celebrity idols lack that complexity: They seem to occupy a single, tidy identity; loving them is occupying a constant lack. For some, that gap between self and ideal is simply the driving force of the psyche: constantly striving for what we are not. For others, especially teens, it’s the font of depression and existential despair.

Helbig’s looks are still an ideal. That’s something, for better or for worse, that has helped make her an authority: Teens, ever self-conscious, initially glom to her because she seems to have negotiated that dominant ideal. But hidden within that ideal package is a disruptive, even revolutionary message: Performing for boys matters for less, ultimately, than cultivating your own self.

What’s remarkable, and heartening, is the way in which girls seem to be responding to this message. Unlike the still relatively old-fashioned star-producing apparatuses of film, television, and music, which offer a star up with the expectation that fandom will follow, Helbig’s fandom is wholly organic. She’s not a star because a group of producers and publicists decided she would be, but because teen girls decided she was. Instead of fans molding their tastes and ideals around what’s offered to them — often by older, male executives — they’ve anointed someone who resonates with them.

Bottom-up celebrity, instead of top-down. It’s dangerous to be too utopian about the potential of YouTube stars to usurp dominant ideals — physically, Helbig fits them perfectly — which is part of the reason that E! has hired her as an ostensible replacement for another unruly yet beautiful blonde, Chelsea Handler. And as Hollywood becomes increasingly aware of the potential of these idols, it’s not difficult to imagine a not-so-distant future in which YouTube stardom becomes just as organized, corporate, and inorganic as the Disney star factory.

To be clear, no one should confuse the value of virtual idols like Helbig for actual role models, whether they be mentors, teachers, or other women who demonstrate and speak frankly about the realities of negotiating femininity in the 21st century, in the lives of teenage girls. Still, I can't stop thinking about how revolutionary Helbig’s weirdo performance of self would’ve been to 12-, 14-, and 16-year-old me.

I’m too old to be a Grace girl now. But I wonder how much more liberated and confident in my own weirdo self I would be if I could’ve been.