GREAT FALLS, Montana — On the first scorching hot day of Montana summer, Trump fans had been lined up outside the Four Seasons Arena in Great Falls, since 4:45 a.m. It was the first Trump rally in any direction for hundreds of miles, and many of those waiting had traveled for hours to see their president. One man pushing a baby stroller and wearing a shirt with a map of the US overlaid with “Fuck Off, We’re Full” had driven 12 hours from Gillette, Wyoming — and was dismayed to find that the line snaked back more than a mile and a half.

Great Falls is difficult for even locals to describe: It’s a military town (45% of the local economy is linked to the local Air Force base); it’s a retirement town; it’s a former mining and union town, scarred, like many other places in Montana, by the decline and eventual collapse of the industry. But it’s also a farm town, and the “big city” to thousands of rural Montanans who make a living farming what’s known as the Montana “Golden Triangle,” a stretch of land by turns beautiful and desolate, depending on the season.

Inside that Golden Triangle, you’ll find the home of Democratic Sen. Jon Tester, who farms lentils, safflower, peas, and winter wheat 12 miles outside the town of Big Sandy. Tester is what Montanans sometimes call a “gravel-road Democrat”: one of decreasing number of Democrats from rural areas, particularly adept at speaking to working-class voters. When he was young, Tester lost three fingers to a meat-grinding accident, a point that’s become emblematic of his authenticity. His hair is cut in a flat-top he hasn’t changed in decades. He has a demeanor that could be described as “jovial uncle,” until he’s faced with incompetence — at a Senate committee hearing regarding the mismanagement of the Indian Health Service, he put on his reading glasses and interrogated the head of IHS like a deeply disappointed schoolteacher.

Jon Tester is why Trump was in Montana — and in Great Falls, the closest city to Big Sandy, in particular. In April, Tester, ranking minority member of the Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, released a report questioning the suitability of Trump’s pick for VA secretary, Rear Admiral Ronny Jackson. The report included allegations that Jackson — who had served as the presidential physician to both Trump and President Obama — was known as the “candyman,” willing to distribute prescription medicine inside the White House, drank on the job, and oversaw a “toxic” work environment.

Jackson withdrew his nomination, but Trump was furious — and fired back at Tester on Twitter, calling him “dishonest and sick,” and calling for his resignation. “I think Jon Tester will have a big price to pay in Montana,” he told Fox & Friends in April. Thursday night, Trump — joined by Tester’s opponent, Matt Rosendale, along with his son Donald Trump Jr., Rep. Greg Gianforte, and Sen. Steve Daines — touched down for a two-hour rally in Great Falls, against a backdrop of banners that read “PROMISES MADE, PROMISES KEPT.”

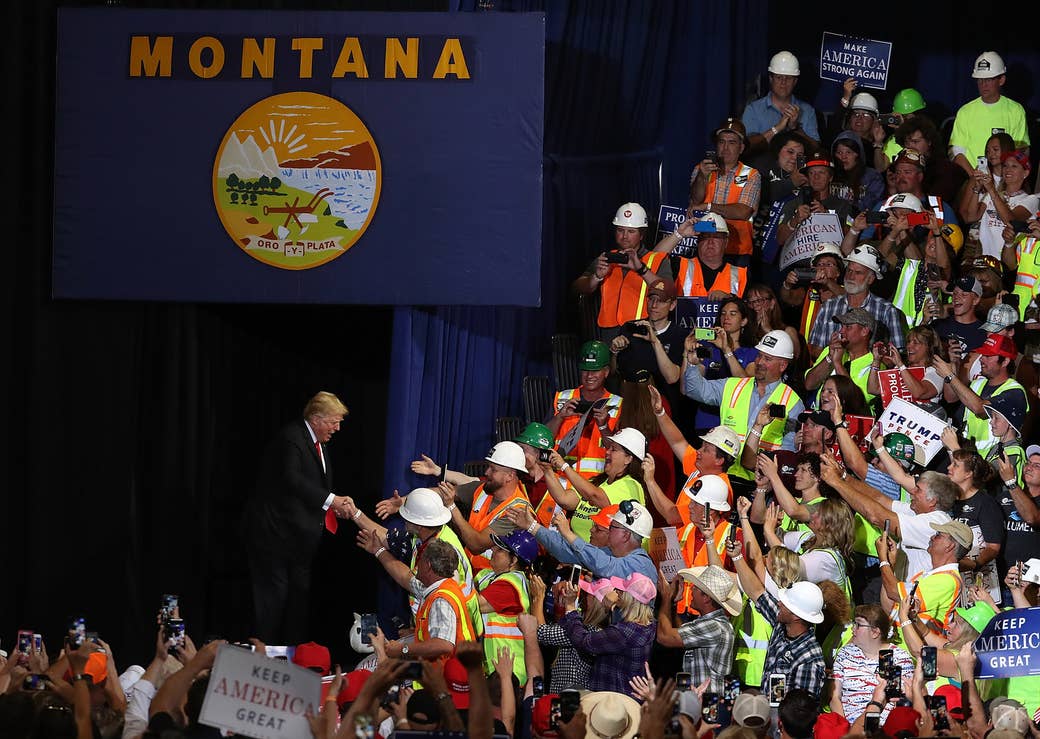

Halfway through his remarks, Trump declared that he won Montana “by so many points that I don’t have to come here!” Shortly before, detailing all the ways he believes Tester had failed the people of Montana, he asked the crowd, “How did Tester even get elected here?” And while Trump won the state by 20 points, both statements point to a misunderstanding of Montana politics and voters, and Tester’s chances in the fall. Trump attracted a capacity crowd of 6,600 in Great Falls — a crowd that cheered for subjects as various as meeting with Vladimir Putin, locking Hillary Clinton up, “beautiful clean coal,” job creation, the end of the Paris Climate Accord, and the press being “really bad people.” But Trump’s misread of both Great Falls and Montana speaks directly to the very real challenges that GOP candidates face in the midterms — especially those running in places often misleadingly labeled as “red states.”

Depending on who you talk to, Great Falls is a Trump stronghold or the seat of a highly contested county, a place the president understands as crucial to his 2016 win and to any Republican who runs in this state. The reality is a little more complicated: In 2016, Trump won Cascade County with 57% of the vote. But in 2008, Barack Obama won with 49.9%. Bill Clinton won in 1992 and 1996. Trump’s own win in 2016 was offset by 8% of the county who voted for an independent candidate. That same year, Steve Bullock, the state’s Democratic governor, won the county handily, with 54% of the vote. And back in 2012, Tester beat his Republican opponent here by 10%.

All of which is another way of saying that Great Falls — a major city that often gets passed over in favor of its more traditionally photogenic, “cooler” Montana siblings — is a useful stand-in for the politics of the state at large: a state that prides itself on its “purple” voting history, on principles as increasingly foreign as “voting for the person, not the political party,” as one resident put it, and maintaining a devotion to voting across ticket. (To state again: 20% of Montanans voted for Trump and their Democratic governor, in the same year, on the same ballot. No wonder that governor is rumored to be considering a 2020 run for president.)

While thousands lined up outside the auditorium, a group of counterprotesters began to grow in their designated spot, right outside the area used for livestock during ag events. While the 100 or so were vastly outnumbered by those in line for the rally, their perspective on Trump, Tester, and their respective relationships to Montana politics echoes those that I’ve heard all over the state, from ranchers to liberal activists in Missoula: Flatten Montana politics at your peril.

Some protesters were from Great Falls Rising, an Indivisible-like group that coalesced after Trump’s election and sprung into action around the special election for the Montana Congress seat back in May. But many at the counterprotest had heard about the rally via the local newspaper, which still functions as a primary news source for many in the extended area. Jerri had driven just under two hours from the tiny farming community of Geraldine after reading the paper and finding the link to the protest on Facebook. “One reason I felt compelled to be here is because I don’t feel that Trump is listening to everyone,” she said. “He’s only listening to his base.” Or, as two women in their seventies who’d driven five hours from Troy, Montana, put it: “It was important for us to be present — and to show Trump that not everyone wants him here.”

Like many counterprotesters I spoke to, Jerri fully expected to see people she knew walking by on their way into the rally. That’s the reality in places in and around Great Falls: You simply can’t segregate yourself by politics. Like many residents, Marina Lambaren came to the area to retire — her husband is a veteran and liked the small-town feel of the place. But she was originally from California, the granddaughter of Mexican immigrants, and furious about the treatment of immigrant families under the Trump administration. She swallows her differences with Trump-supporting friends, but was adamant about being present at the counterprotest, which she heard about from her friend Elise Swan, who works at the casino that she and many other retirees in the Great Falls area frequent. “As a liberal, and as an outspoken Native female, I wanted to be here. Tester is our ally,” Swan said, holding a sign that read “SAGE AGAINST THE MACHINE.” “Especially for my tribe, the Little Shell, who are still battling for federal recognition.”

Swan’s customer base is largely retirees, and largely Trump supporters. But that doesn’t mean they’re against Tester. As Lambaren was keen to point out, “Tester does have a good following of Republicans who are veterans.” A veteran holding a “Tester for Montana” sign told me something similar: “I work in an office where everyone but me is Republican,” Dave Glaeske said. “Trump makes these attacks against Tester, which might be effective for some people. But they’re not effective for vets in Montana, to anyone who’s ever met him.” And in a place like Montana, that’s a surprisingly large percentage of the voting population.

One woman stood at the front lines of the protest with a sign that read, “TOXIC MASCULINITY RUINS THE PARTY AGAIN.” Her husband works at Malmstrom Air Force Base, and her friends cautioned me against using her name. “A lot of people at the base are excited for Trump to come. But a lot are peeved, too. He has no plans to come visit. He’s not meeting the troops. He’s just campaigning for an Easterner.” She was referring to Tester’s opponent, Rosendale — a real estate developer who moved from Maryland to a Montana hobby ranch in 2002.

As to whether or not veterans and military personnel will heed Trump’s attacks on Tester, she hesitated to answer for the base. “But Montanans are able to make up their own mind, especially when it comes to an Easterner,” she said. “Trust me, I know — I’m from the East.”

Tester’s campaign is focused on how their candidate stands up for and represents Montanan values, and his team has taken to calling Rosendale “Maryland Matt.” No one used that name to describe him at the protest, but they all knew he was not from Montana — a point driven home by Rosendale’s thick Maryland accent, arguably his greatest liability in a place where candidates on both sides argue about how many generations their families have been in the state.

Inside the rally, Trump attempted to turn this message against Tester: Tester says one thing in Montana and another in DC. He may seem Montanan — but his real loyalties lie with Chuck Schumer and Nancy Pelosi, those liberal bogeymen carted out as a means of discrediting Democrats in their home states. Trump drove home the fact that Tester voted against the confirmation of Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch, he voted to block a bill that would ban late-term abortion, against the repeal of the Affordable Care Act, and against the Republican tax cut bill. Tester, Trump said, was a liberal — someone who didn’t represent Montana values. Each time Trump mentioned what he saw as an un-Montanan vote, the crowd roared in approval. (Often, reporters are allowed to roam the crowd and speak to supporters before the rally; this time, we were penned in a press cage, unable to leave for the bathroom or water — which made confirming Trump’s message about Tester with his supporters difficult.)

“I find it hard to believe that Montanans will really go for that,” Beatrix, a Great Falls counterprotester, told me. “Except for his really strong supporters,” she added, gesturing to the auditorium. “The type who are in there.” And while that crowd cheered when Trump said that he couldn’t understand how Montana elected someone like Tester, the vast majority of Montanans, liberal or independent or conservative, know exactly how he got elected, even if they didn’t vote for him.

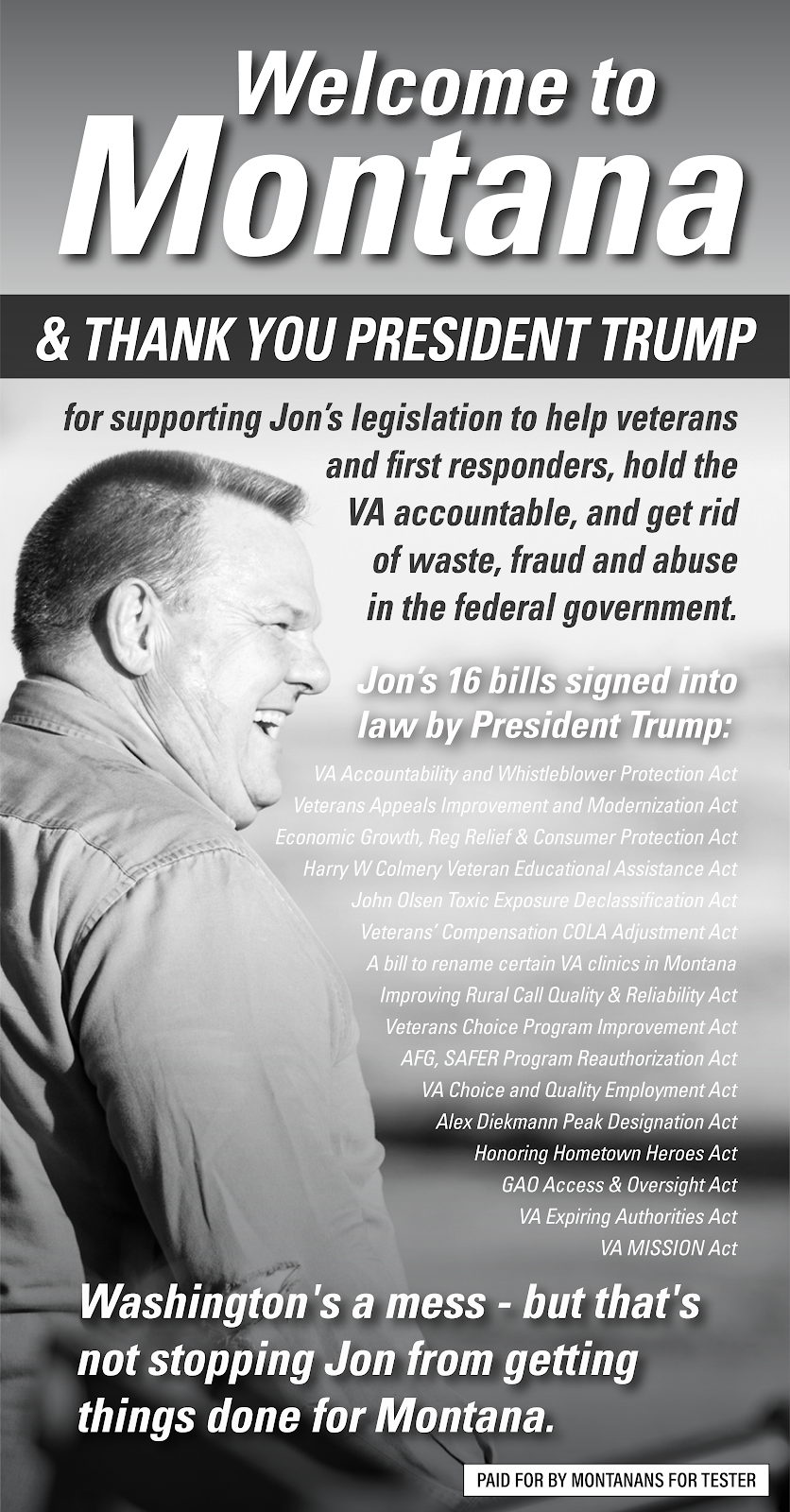

That morning, Tester had taken out a full-page ad in the Great Falls Tribune and 13 rural papers across Montana. “Welcome to Montana, and Thank You President Trump” the headline read, “for supporting Jon’s legislation to help veterans and first responders, hold the VA accountable , and get rid of waste, fraud and abuse in the federal government. Washington’s a mess — but that’s not stopping Jon from getting things done for Montana.” The ad then listed 16 Tester-authored bills, including two touted as achievements by Trump during his speech — without mentioning Tester’s authorship. Meanwhile, across the state, from Miles City to Kalispell, from Billings to Butte, supporters registered voters and canvassed for Tester and Gianforte’s opponent, Kathleen Williams, in an organized day of action. (Polling in Montana, like in many rural states, is often unreliable, but the most recent numbers show Tester up by seven points and Williams up by six for the upcoming midterm elections.)

That’s the thing about Montanans, cliched but true: As rousing as this rally was, as a whole, residents prefer action, on whichever side of the political spectrum, to words. When Trump geared up to introduce Matt Rosendale, he told the crowd, “You deserve a senator that doesn’t just act like he’s from Montana. You deserve a senator who actually votes like he’s from Montana.”

But apart from voting like Trump, the president was vague on specifics as to what would make Rosendale a good representative for the state. Does it mean overseeing medical insurance premium hikes, as Rosendale did in his capacity as Montana state auditor? Does it mean commissioning legislation to support and protect veterans? Does it mean fighting tariffs poised to adversely affect Montana’s ag and mining industries that went into effect first thing Friday morning? Or does it mean aligning oneself absolutely with Trump’s politics?

After Rosendale’s intro, my phone buzzed with a text from an Eastern Montanan who, last year, had admitted she was one of the fabled cross-ticket voters: She’d voted for both Trump and Bullock. “Absolutely nothing about what Matt would even *do*,” she texted, going on to quote the president: “I won Montana by so many points, I don't have to come here.”

“First rule of politics,” she said. “Never assume you’re untouchable.” ●

CORRECTION

Jon Tester lost his fingers in a meat-grinding accident. A previous version of this post said he was injured by a thresher.