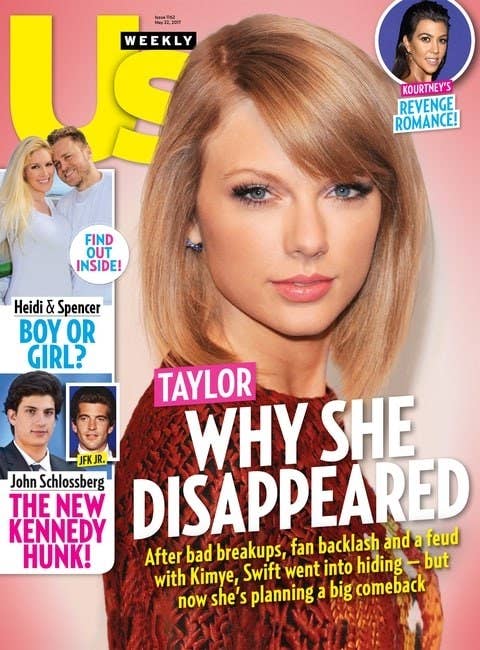

On May 22, the cover of Us Weekly promised to reveal the answer to a question that many readers might not have realized they’d been pondering. The headline read “Taylor: Why She Disappeared,” with a subtitle that suggested Swift had gone into “hiding” after bad breakups and a feud with Kanye — but was planning a comeback.

The article cites “sources close to Swift,” claiming she’s been working on an album that will drop this fall. But it also points out how complete her absence has been: She’d made just one public appearance at a pre-Super Bowl performance, on Feb. 4, but otherwise, she hadn’t been seen or photographed in public since January. In three months, she's posted just twice to her once meticulously updated Instagram: once, to celebrate the release of Lorde’s new album, and again to promote the women of HAIM’s new single.

Whether or not Swift is simply taking a publicity sabbatical, the fact remains: our most popular, visible, and successful white female celebrity has been invisible for nearly six months. Meanwhile, other major white female movie stars, musicians, and celebrities are struggling — to earn our attention, to keep our interest — in what amounts to a generalized disinterest or even disavowal of so many of the women who have dominated headlines, magazine covers, and Instagram feeds for the last five years.

Call it a great white celebrity vacuum — or the continued erosion of old-school, white star power. Either way, the entertainment industry at large is struggling with how to serve those alienated by white womanhood — but also those, on the opposite side of the cultural spectrum, desperate to sustain it. It’s no accident that the most popular (and polarizing) white female celebrities aren’t entertainers, but politicians. Hillary Clinton, of course, but also Ivanka Trump — whose particular blend of white, polished, privileged femininity has taken on incredible significance: as an ideal, or as precisely what women define themselves against. To put Ivanka on the cover of your magazine is to please one half of your readership — and alienate the other.

Within the industry of celebrity, white women have long been the primary currency. But in our current political and cultural climate, investing in them feels increasingly ill-advised. Could the long, oft-contested, and consistently fraught reign of white celebrity womanhood be coming to an end?

Think about it. Image rebrands from Miley Cyrus and Katy Perry have flopped. Scarlett Johansson's last two movies have either flopped (Ghost in the Shell) or underperformed (Rough Night). After the disappointment of Passengers, Jennifer Lawrence has also gone MIA. Angelina Jolie hasn’t starred in a movie since 2015, when By the Sea failed to break $500,000 at the box office — and, apart from the announcement of her separation from Brad Pitt, she has kept out of the press.

And the list goes on: Jennifer Aniston has basically become an ensemble star in B-movies you watch on airplanes. Jennifer Garner is apparently now a Christian movie star. Gwyneth Paltrow and Reese Witherspoon are less movie stars than lifestyle avatars. Britney Spears is boring. Lorde is beloved but the pop equivalent of prestige cable television. Kristen Stewart’s returned to the indie world. Brie Larson refuses to talk about her love life or do anything scandalous enough to make her compelling. Lena Dunham’s Girls is over. Amy Schumer’s book tanked and so did Snatched. Tina Fey and Amy Poehler are producing, not celebritizing. Sure, the white-lady-filled Big Little Lies was a hit, but it was also an indictment of bourgeois white womanhood and the hypocrisies at its core — and the latest example of huge movie stars moving into quality TV.

Recent covers of Us and People are filled with old favorites (Olivia Newton-John, Goldie Hawn), British royals, and the occasional favorite of the minivan majority (Garner, Katherine Heigl). For its “Most Beautiful Woman in the World,” People chose Julia Roberts — for the fourth time since 1990. The recent obsession with the sparklingly toothed, wholly wholesome HGTV stars (Chip and Joanna Gaines; Property Brothers' Drew and Jonathan Scott) highlights just how barren the celebrity landscape has become. It’s not that they’re reality stars — the stars of The Hills and Jon and Kate Plus 8 dominated the gossip mags throughout the late 2000s — it’s that they’re boring reality stars whose ratings pale in comparison to their predecessors.

Which isn’t to suggest that white female celebrities have disappeared: There are dozens of them, at all echelons of fame, making millions of dollars and attracting devoted fans. But none are ascendant: They’re at a plateau or starting the downswing of their careers, not the beginning. “The whole category [of gossip magazines] is really struggling to figure out where to go,” according to former Us Weekly and Hollywood Reporter editor-in-chief, Janice Min. “You’re seeing the continued erosion of traditional star power and the effects of a culturally divided America.”

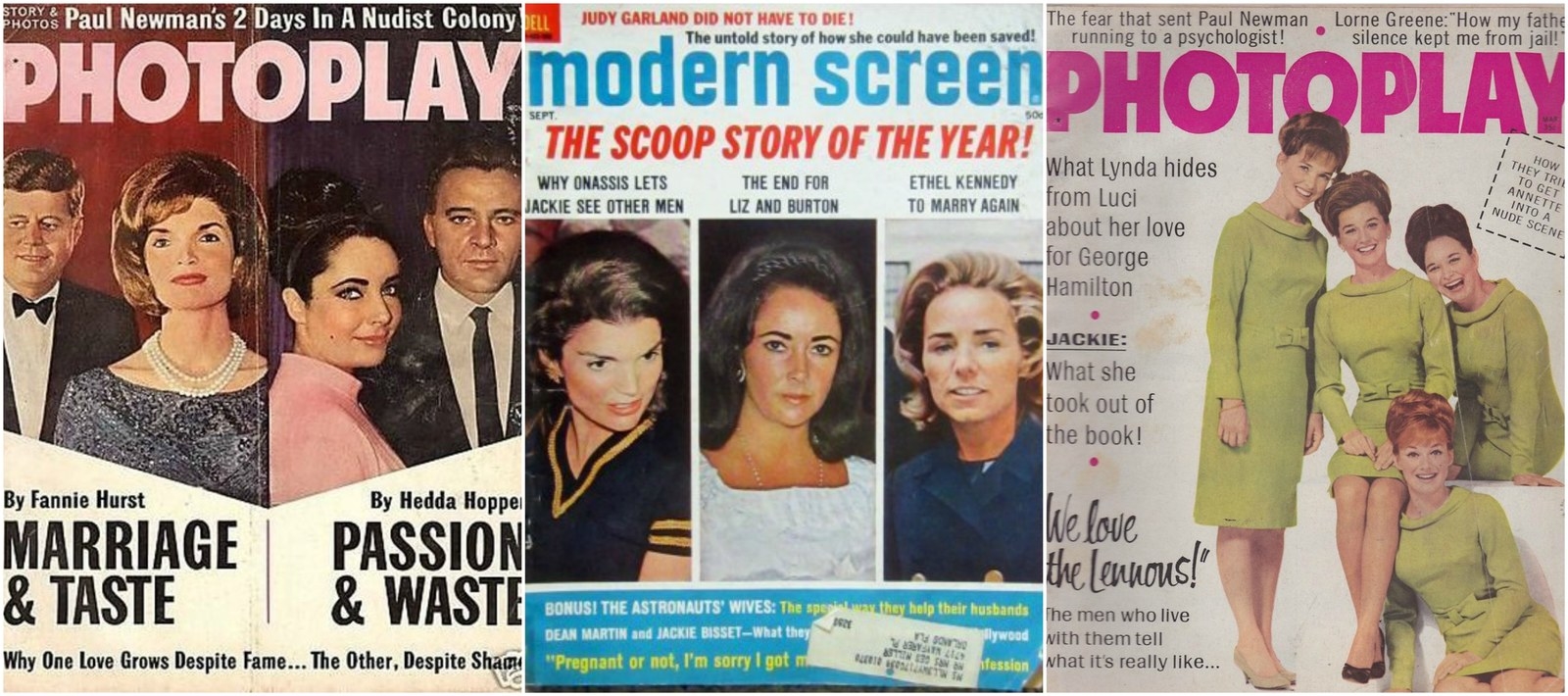

This isn’t the first time this has happened. In 1967, the Hollywood fan magazines were in freefall. These magazines, with names like Photoplay, Modern Screen, and Motion Picture, had collaborated closely with the studios, serving as the de facto arbiters of stardom for decades. But over the course of the 1950s, the studio system endured a slow-motion collapse — the studios themselves would remain (and flourish, even to this day), but the system of star production, in which the raw star material of handsome men and beautiful women were fashioned into polished Hollywood products, had broken down.

Television and music stars — people like Dick Clark and Elvis — seemed more interesting, especially to the newly ascendant teen demographic. Those teens also fell hard for stars like Marlon Brando, who embodied the new ethos of rebellious yet emotive masculinity — but infuriated the fan magazines by refusing to sit for interviews or pose for pictures.

Brando’s posture toward the fan magazines soon became the norm, and the fan magazines began to get desperate, experimenting with expanding their focus beyond Hollywood. In 1962, for example, Photoplay declared Jacqueline Kennedy “America’s Newest Star.” And while the magazines could obviously assert anyone as a star that they wanted, it was harder to figure out which stars actually sold magazines — or, put differently, which stars were actually resonating. By the late ‘60s, covers featuring Kennedy, First Daughter Lynda Johnson, or First Lady Lady Bird Johnson were far more reliable than those with movies stars. As Helen Weller, editor of Modern Screen, told the Los Angeles Times, “finding a movie star to put on your cover every month is a hard sweat. After Liz, there’s nobody.”

Weller was referring to Elizabeth Taylor — whose private life, much like Taylor Swift’s, played out like an irresistible soap opera. Liz just married all of the men she fell in love with, instead of simply writing songs and Instagramming about them. In the process, she developed an image that combined liberated sexual appetites — and defiance of social mores — with the memory of her previous National Velvet and Father of the Bride wholesomeness. The intense reaction and attraction to her mirrored (white) America’s own conflicted reaction to the seismic social changes of the ‘60s.

Jane Fonda’s image had once accomplished something similar, but by the late ‘60s, she’d become far too radical for the fan mags. Brigitte Bardot was too foreign; Audrey Hepburn too boring; Barbra Streisand too ethnic. The reliance, around 1969, on covers featuring Ethel Kennedy and the Lennon Sisters — a group of singing sisters featured on The Lawrence Welk Show — highlights just how little 1969 America, as a celebrity-consuming whole, could agree on.

Of course, a new star can be made nearly overnight. But that only happens when their image, their way of being in the world, seems to reconcile the contradictory impulses of the moment. In the ‘70s, it took the likes of Farrah Fawcett to find a star who embodied the ‘70s ideal of the sexually liberated sex object. In the ‘90s, it took Julia Roberts — playing a prostitute who wanted a consumerist fairy tale. And in the mid-2010s, it took Jennifer Lawrence, whose image crystallized the liberatory impulses of feminism mixed with the desire to make oneself amenable, low maintenance, and “cool” to dudes. Her appeal — to men and women, to liberals and conservatives — was as close to universal as it gets in contemporary Hollywood.

But there’s no new Jennifer Lawrence, and the air around Taylor Swift has soured — in part, because the political centers, and the ideologies that underpin them, have moved so far apart that no star image can reconcile them. (Even Chris Pratt, who was heralded, post-election, as “the last thing we can agree on,” proved otherwise after his comments about a lack of representation of blue-collar Americans in Hollywood read, to many, as proof that he had voted for Trump).

The white celebrity vacuum, then, suggests that ideals and expectations of womanhood, and white womanhood in particular, are in flux. Of course, you could point to badly marketed movies or album cycles, which certainly contribute to the absence. But the overarching reason has much more to do with how the election — and the fact that 53% of white women voted for Trump — has revealed the fault lines in the celebrity-sustained myth of the well-intentioned white woman.

Put differently, it’s increasingly hard for many women — women of color, but also white women — to trust or idealize white women. White women in our everyday lives, white women as voters, white women on juries, and, by extension, white female celebrities, who have repeatedly fumbled or ignored the conversations of race, class, and gender that, in this hyperpoliticized moment, seem most vital and urgent. Which explains the sustained reign and resonance of women who do seem to be working through those issues, explicitly or implicitly: Beyoncé, of course, but also Rihanna, Nicki Minaj, and Shonda Rhimes, Serena Williams, and Michelle Obama, and so many other stars coming to the fore who feel representative of the future, not some anxious tether to the past.

No celebrity emblematizes this general distrust in white celebrity — and the well-intentioned, yet inwardly focused white woman in particular — more than Taylor Swift. Swift’s image has long been rooted in a vision of vulnerable white innocence, and just the latest version of a trope that's been forever central to the American conception of femininity. Early in her career, she avoided or averred when it came to questions of personal feminism, responding “I don’t really think about things as guys versus girls. I never have. I was raised by parents who brought me up to think if you work as hard as guys, you can go far in life.”

But with the 2014 release of her album 1989, questions about her relationship to feminism became impossible — or at the very least, deeply unfashionable — to dodge. And so, over the next two years, Swift became the figurehead for a certain type of feminism: one that largely defined itself as “supporting other women” and “having girlfriends that you post pictures of on Instagram.” This Swiftian brand of feminism was highly individualistic (see: her response to Nicki Minaj), selectively vindictive (see: her feud with Katy Perry), and seemingly opportunistic, with little attention given to the larger structures of power within patriarchy — or acknowledgment of the privilege that Swift enjoys.

Swift’s feminism is a white, straight, rich, skinny girl feminism: nonintersectional, lacking substance, strategic. After claiming she denied giving Kanye West permission to use the lyric “I made that bitch famous” — a claim that was rebutted when Kim Kardashian made tape of the conversation available online — cultural critic Damon Young called her “the most dangerous type of white woman.” Women like Swift, according to Young, employ “the inherent empathy and benefit of the doubt her White womanhood allows her to possess ... to throw a Black person under the bus if necessary and convenient.”

At that point, in July 2016, Swift may have revealed herself to be deeply invested in maintaining a posture of victimhood — but that toxicity hadn’t yet spread to the rest of her image. Cut to the height of the presidential campaign, when many of the women invited into Swift’s “squad” voiced their support, in ways both small and flamboyant, for Hillary Clinton. Swift, however, remained conspicuously silent. It was a pragmatic decision: She understands the political breadth of her fan base and, having come up through the ranks of country music, witnessed what happened to the Dixie Chicks when they spoke out against President George W. Bush in 2003. But for someone who’d publicly performed so much of her “personal” life — her relationships, her friendships, her philanthropy — her political privacy was striking.

Or, for some proof that she probably voted for Donald Trump. In many ways, Swift resembles the Ivanka Voters who helped tip the election toward Trump: white, upper-middle-class women from the suburbs who describe themselves as “socially moderate,” would never think of themselves as racist, and likely even voted for Obama in previous elections. They’re embarrassed by Trump, but love the “empowered classy woman” that his daughter Ivanka represents — and are willing to forgive Trump’s crassness for his fiscal policy. Like Ivanka, they like to say they “stay out of politics,” and simply advocate for the issues that matter to them (better schools for children but only their children, lower taxes, “keeping America safe,” etc).

Swift grew up upper-middle class in Wyomissing, Pennsylvania — a deeply white suburb of Reading, Pennsylvania, that, like many other white suburbs, swung from voting for Obama in 2008 to Trump in 2016. Of course, growing up in a place that largely voted for Trump does not mean that someone definitely voted for Trump. But the specifics of Swift’s background, her political silence, and the flimsiness of her feminism — which, like Ivanka’s version of “female empowerment,” empowers only a certain type of woman — certainly makes it easier to believe that she did.

Ahead of her rumored new album, Swift’s image, at least at this point, hasn’t changed. But the tolerance for that particular brand of nonintersectional, opportunistic feminism has — whether it’s hers, or Miley Cyrus’s, or Katy Perry’s, or Scarlett Johansson’s.

A celebrity does not have to be explicitly political to become a massive celebrity. But her image must subtly suggest a solution — or, at the very least, provide a salve — to the tensions in a societal moment. And in this moment, the vast majority of white women, regardless of their personal political persuasions, serve as inflammations.

The dominance of female celebrities have always, in some way, been a testament to the endurance of white supremacy. The election of Obama and the so-called “browning” of America created an anxiety that some assuaged by voting for a different kind of celebrity who promised to reverse it. For many, the lived reality of that decision is too much to bear — and certainly too much to be reminded of while consuming entertainment.

There might be a white female celebrity around the corner, just waiting to make people feel better about white women in America today. Taylor Swift might heal the world, but I doubt it: This might not be the moment when whiteness ceases to rule the celebrity industrial complex, but it could be the rupture that shows that it doesn’t have to.