Drive down John Wayne Drive in Winterset, Iowa, and you’ll find it: the John Wayne Birthplace Museum, designed with an imperative to make it “timeless and masculine.” There’s a bronze of Wayne, splay-legged; across one street, there’s a garage filled with tractors; across the other, there’s a makeshift war memorial, perched on a trailer with “PROUD TO BE AN AMERICAN” emblazoned on the side. Winterset, population just over 5,000, is the type of town where students toilet-paper friends’ homes in anticipation of homecoming and the Wednesday night special at the local diner is ham balls. When I drive into town, the sky’s a perfect shade of Midwestern blue-black, and the lights of the courthouse square — one of the best preserved in all of America, according to various proud brochures and friendly waitresses — can be seen for miles.

Until this May, the birthplace museum was little more than a humble, sleepy old house, believed to be where the 13-pound infant Wayne came into the world as Marion Morrison, and a van, airbrushed with scenescapes of Wayne, straight out of the ‘80s. But under the management of Museum Director Brian Downes — a former Wild West performer and travel writer — the museum raised $2.5 million for a building that includes a small theater, an expansive gift shop (best-selling items include a tin sign with Wayne holding a rifle beside “THIS COMMUNITY PROTECTED BY NEIGHBORHOOD WATCH,” and The Official John Wayne Way to Grill) and a gallery, about the size of a large Starbucks, where all manner of Wayne trinkets are arranged into three thematic areas: "Movie Star," "Family Man" (his massive station wagon, customized by Pontiac so that The Big Man could easily maneuver), and "American."

Some artifacts are more suggestion than fact — it’s easy to make the conclusion that a pistol displayed in one of the exhibits was one used, by Wayne, on set; in fact, it’s from Downes’ personal collection, placed for ambiance. That’s the guiding thesis of the house, still snuggled behind the main museum, where visitors can imagine that the tiny, metal-springed bed in the kitchen would’ve been where toddler Wayne slept, or the glass bottles on the shelf, dug out from the backyard, were Wayne’s family refuse. The family was there for little more than two years, and left little trace on the Winterset public record save Wayne’s birth certificate. But it’s easy to imagine all of these things to be true, even if the only evidence that the house in question was Wayne’s birthplace comes from a neighbor, decades after the fact, who remembered a commotion at the house the day Wayne was born.

Inside the house, a tiny, white-haired woman named Ruth takes both my hands in hers and holds them for a solid three minutes, asking warmly where my people are from. She leads me through the house, narrating “Marion’s” early life, rounding out a few of the details of Wayne’s father’s life and his future accomplishments. It’s not that Ruth, who’s lived in Winterset since the late ‘60s, is fibbing — she’s just the latest to sing the refrain in what has become the well-practiced ballad of John Wayne.

The image of John Wayne on offer at the museum is a tapestry of half-truths and tall tales, a myth meant to assuage a nation’s anxieties and assure its citizens that a certain type of man, with a sort of principle, was still central to American identity. It’s also a contradiction: an evocation of an idyllic past that never was, a man who only played at, but never actually lived, the wars and skirmishes and shoot-outs that served as a testament to his character and the foundation of his image.

He’s a conservative whose gravitas and charm can sway even the archest of liberals, a man who disliked horses but, more than any other figure, came to represent the entirety of Western ideals. Who avoided military service during World War II but became a hawkish supporter of Vietnam, and whose code of integrity was shadowed with racism, sexism, and thinly veiled bigotry, publicly stating his belief “in white supremacy until the blacks are educated to the point of responsibility” and calling the Native Americans “selfish” for refusing to hand their land over to white settlers.

And yet: He’s so difficult to resist. He’s charismatic and charming, with a hypnotic onscreen presence and a drawl that sounds like a gruff lullaby. He was a top box office draw for nearly 20 years; in 1995, 16 years after his death, a national poll voted him America’s favorite movie star. There’s a sense that he’s always been, always will be. He’s like the racist grandpa that millions of Americans nevertheless acknowledge as their own; he’s the embarrassing tear in your eye when you root for America in the Olympics or watch a good Chevy commercial. He’s a mansplainer; he’s a xenophobe; he’d probably have horrible things to say about Islam. And Obama. And trans rights. And so many of the issues that are shaping the future of our collective identity.

The West is gone; the frontier is closed. But the same craving for an idealized version of it, complete with “traditional” gender and race dynamics that accompanied it, has regained currency, legitimacy, and airtime — through the museum, where Donald Trump recently made a campaign appearance, and in texts like The John Wayne Code: An American Conservative Manifesto, filled with quotes from “John Wayne, American Conservative.”

Wayne’s image has long been yoked with ideals of Americanism, patriotism, and liberty. On the surface, those ideologies are hard to decry — they’re the building blocks of our nation! — but the Wayne-inflected versions are undergirded by a dark and unspeakable fear: of change, of difference, of anything that threatens the primacy of a white, masculine, heterosexual world. Over the last 50 years, that fear has been explored, interrogated, and decried: Playing "cowboys and Indians" isn’t just un-PC, but flatly racist; anti-miscegenation laws feel like a relic of another time; cowboys can be gay, and feminist, and women. And yet a desire to return to Wayne’s America nevertheless remains strong: Just because a thing never existed doesn’t mean people don’t yearn for it anyway.

But how did Marion Morrison became John Wayne, and, in turn, the ultimate embodiment of those values? He went west.

Wayne became a movie star three times. Each time, there was a different publicity campaign intended to introduce and solidify his stardom, and each time it emphasized slightly different values. It wasn’t until the third try — when Wayne’s boyish beauty had receded, when he’d accumulated the addled look of a divorced father of four, when the plots were less about taming him and more about him taming others, that Wayne finally became a true movie star.

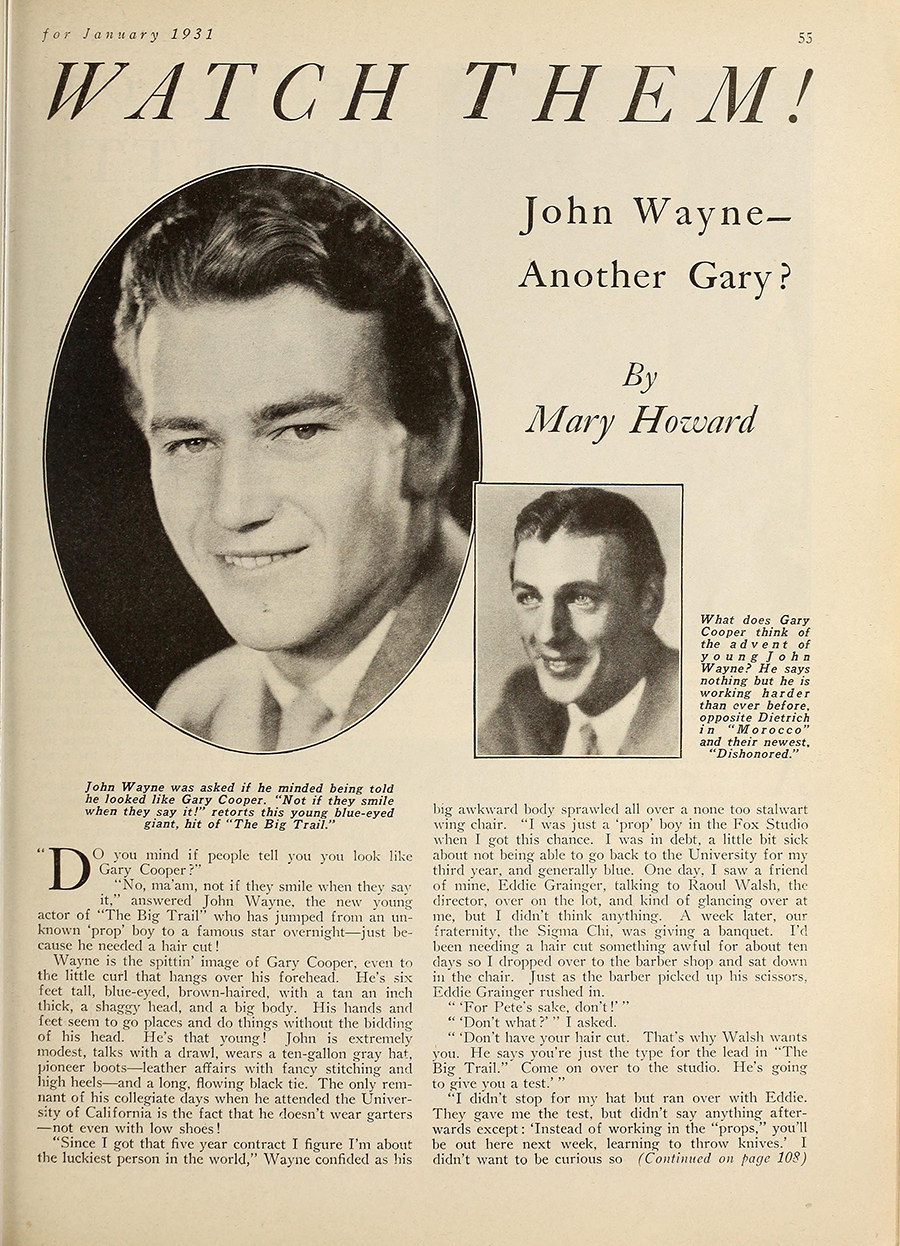

The first try came in 1930, when Wayne, then 23 years old, appeared in Raoul Walsh’s epic Western The Big Trail. Up to that point, Wayne had just been a college student working at the studios to help cover tuition. But after his sophomore year, his mediocre football skills meant the end of his scholarship at the University of Southern California, and he started working full time as a “juicer” (electrician’s assistant) and prop boy. He got chummy with director John Ford, but his break didn’t come until Walsh saw him moving scenery and thought he had the sort of build that a Western boy would. He was told not to cut his shaggy hair, which would make him seem more feral, and sent him on location, where he was dressed in the fringed suede of a Western hero.

The Big Trail was a massive production that failed for various Depression-related reasons, but the studio worked hard to make a star out of Wayne. They changed his name — Marion was “too feminine,” so Walsh suggested “Wayne” — the surname of a Revolutionary War general. Wayne still went by his childhood nickname of “Duke,” which, on another man, could’ve connoted something like royalty, but on the newly christened Wayne, it just gave a sense of something hard and masculine.

“John loves to fight better than anything,” an early profile reported. “After that, he likes to eat: ‘I like meat. Plenty of it. Almost raw. It seems I can never get enough to fill up this big carcass of mine.” Hollywood Magazine reported that “he gets to champing at the bit, feeling a mite coltish,” and has to abscond to the woods. “This movie stuff is alright,” he said, but “this glamour stuff stinks.”

He was repeatedly compared to Gary Cooper: They were both tall and blonde, both had made-up names to make them sound more masculine, and both starred in Westerns. According to Screenland, “John is extremely modest, talks with a drawl, wears a ten-gallon gray hat, pioneer boots — leather affairs with fancy stitching and high heels — and a long, flowing black tie.”

The difference: Cooper had actually grown up ranching and riding in Montana, first finding work in Hollywood as a stunt rider. By contrast, Wayne had been born in Iowa, where his father worked at a drugstore; his family migrated to California, where they first attempted to do something like farming in the desert, before settling in Glendale. Whatever pioneer boots Wayne might have been wearing were new to him — as was the habit of dropping G's that journalists ascribed to him.

Wayne may have played football, but he was no dumb jock: As would become clear later in his career, he was incredibly well-read and articulate; before he was forced to drop out of college, he planned to be a lawyer, and soon married a society girl — Josephine Saenz, the daughter of a Panamanian diplomat. But that was glossed over in favor of narratives that suggested his onscreen performances as an extension of his IRL personality, and when they couldn’t find true West, they built up his football accomplishments, calling him an “All-American” and suggesting his name was all over the papers, even though, as Wayne biographer Garry Wills has convincingly demonstrated, Wayne wasn’t even a college standout, let alone a star.

Wayne was far from the first actor whose backstory was massaged to match with his onscreen image. What’s more interesting is that it didn’t turn him into a star — at least not yet. After the disappointment of The Big Trail, Wayne descended to the land of “quickie” Westerns. These were ramshackle affairs, generally made on shoestring budgets over eight days — some so cheap they’d take silent Westerns from the ‘20s and splice them together with new footage of Wayne on a horse. It was during this time that Wayne acquired the actual skills that, to that point, had been fiction: For five years, he worked alongside rodeo star–stuntman Yakima "Yak" Canutt who, according to observers, “carried himself so that he was ready to get rough on a second’s notice.” Wayne learned his own Western walk, how to fake punches in a way that looked convincing, and how to say things “low and strong, the way Yak talks.”

Throughout this time, Wayne cultivated his friendship with John Ford, whose name, 20-plus films later, would become forever linked with Wayne’s. But at that point, they were just drinking buddies — until, in 1938, Ford cast Wayne in Stagecoach, and Wayne was asserted as a star for the second time.

Only Wayne wasn’t supposed to be the star. Stagecoach was intended as an ensemble picture; Wayne doesn’t even show up until 15 minutes into the film. But when he does, it’s with a hero’s intro: Wayne twirls his rifle as if it were a pistol as the camera zooms in to a glorious close-up of Wayne’s face. It’s become one of the most iconic scenes in classic cinema — and Wayne’s way out of quickie Western purgatory.

Gradually, Wayne became something of a leading man: He was in Ford’s next picture, The Long Voyage Home, as a Swedish fisherman, and played a Navy officer opposite Marlene Dietrich in Seven Sinners. Wayne’s Westernness was treated as a matter of fact: He was, in Photoplay’s words, “the typical Western-American-open-spaced and open-minded.” But the press also emphasized that he enjoyed the finer things: Wayne “dressed with meticulous care, like any well-calfed businessman, looks divine in tux or tails ... He doesn’t whang a guitar or sing sad pieces about Western skies, either.” He lived in an “exquisitely furnished home in the swankiest section of Hollywood” and “has no yen for horses offscreen.”

John Wayne was a truer cowboy, then, because he didn’t act the part offscreen. He worked steadily for the next two years, but was nothing we’d consider a star — more on par with the lead in a TV crime drama. When the U.S. entered World War II in 1941, Wayne was 34 and the father of four, and thereby subject to an official deferral. Yet other Hollywood actors waived their deferrals and went anyway, including Clark Gable (age 41) and Jimmy Stewart (age 33), who, when rejected from the Army for being underweight, enlisted his studio’s trainer to help bring him up to 143 pounds. Ford — who, at 47, became a commander in the Navy and headed up its documentary production — repeatedly urged Wayne to enlist. But Wayne resisted, writing Ford with a litany of poor excuses.

The truth of Wayne’s hesitation was logical, if unspeakable: He’d worked for a decade to claw his way out of the quickies. If he left Hollywood then, even to serve his country, he might not ever regain his momentum. So he stayed put, made a dozen films, two of which dealt with the war, and allowed the press to rationalize his lack of service. As Modern Screen explained, “a man of 35 heading a family of six has to think twice before leaving. Just the same, Big John Wayne is restless because, like I said, he’s a man’s man who thinks straight and believes in action. It’s a dilemma for a family man and an American gentleman who wants to make a personal appearance in The Big Scrap.”

At the end of the war, Wayne watched as Stewart and Gable returned home with medals of honor. It’s said that Ford, who routinely abused Wayne, both physically and verbally, never forgave him. It’s also said that Wayne felt deep shame about the decision his entire life — and that it motivated his extreme hawkishness, decades later, when it came to defending the Vietnam War.

But Wayne did, indeed, sustain his career, and starred in one of the most successful renderings of the war — the Ford-directed They Were Expendable, released in 1945. Behind the scenes, Ford, still furious about Wayne’s refusal to enlist, insulted Wayne’s salute and generally gave him hell; in the film’s credits, Ford listed the naval rank of the cast and crew, including Wayne’s conspicuous lack thereof. Still, Wayne’s ability to play at heroism and service was enough to distract from the fact that he hadn’t served— and also made it possible, two years later, for him to become a star a third, final, and decisive time.

In 1948, John Wayne had been acting for nearly 20 years. He was 41 years old. His face, exposed to the elements of years of shooting Westerns and long afternoons on John Ford’s boat, had already taken on the early wrinkles of middle age. His squinting eyes seemed more skeptical; his eyebrows slightly more worried; his hair whispier and receding, especially in contrast to Montgomery Clift, his co-star in Red River. Directed by Howard Hawks, the film was the late ‘40s version of a blockbuster — and cast Wayne as a gruff asshole, in a narrative that lacked the moral clarity of so many of his previous films.

It was in this mode that Wayne finally, decisively, became a movie star — and it would be in various iterations of this mode that his iconic, enduring image would be forged. If John Wayne had been a guy who stars in Westerns before, from this point forward, he would begin to represent The West, writ large.

As scholar Jim Sanderson explains, up until Red River, Wayne’s “code was not yet formed; he could yet go wrong; he was not yet old enough.” It wasn’t until Red River that he became “the a begrudging tutor for the younger man he once was.” A man who knew enough, who had a certain world-weary wisdom gleaned not from the office, or the university, but the natural world. Who had little time for women, usually because he’d already gone through the game, and emerged a better, if slightly battered, man.

Suddenly, America couldn’t get enough Wayne. Over the next two years, he appeared in six movies, including now-classics She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, Ford Apache, and The Sands of Iwo Jima, all of which espoused the same wearied, wise, and principled Wayne persona of Red River. His higher quality Western back catalog flooded theaters; his shitty ‘30s Westerns started making regular appearances on television. And while the Wayne of these movies was still the unformed, pre-Red River naïf, they suggested that Wayne, like his onscreen character, had been a cowboy forever.

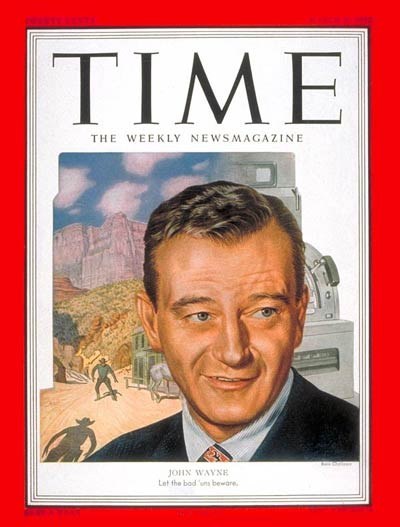

Middle-aged Wayne became a press favorite in a way that beautiful boy Wayne never was. He was voted the Top Male Star of 1951, was profiled by Saturday Evening Post in 1952, and Time magazine put him on their cover that same year, with a warning to “Let the bad ‘ums beware.”

Now, instead of trying to prove his Western legitimacy, Wayne’s press was all about middle-aged masculinity, bolstered by his prowess with women. Even if his onscreen characters regularly eschewed the hassle of female company, it was clear that Wayne liked them around: “Duke’s had a ton of rogue male fun with bottles and sometimes belles, when he was on the loose before and in between his marriages,” one fan magazine reported.

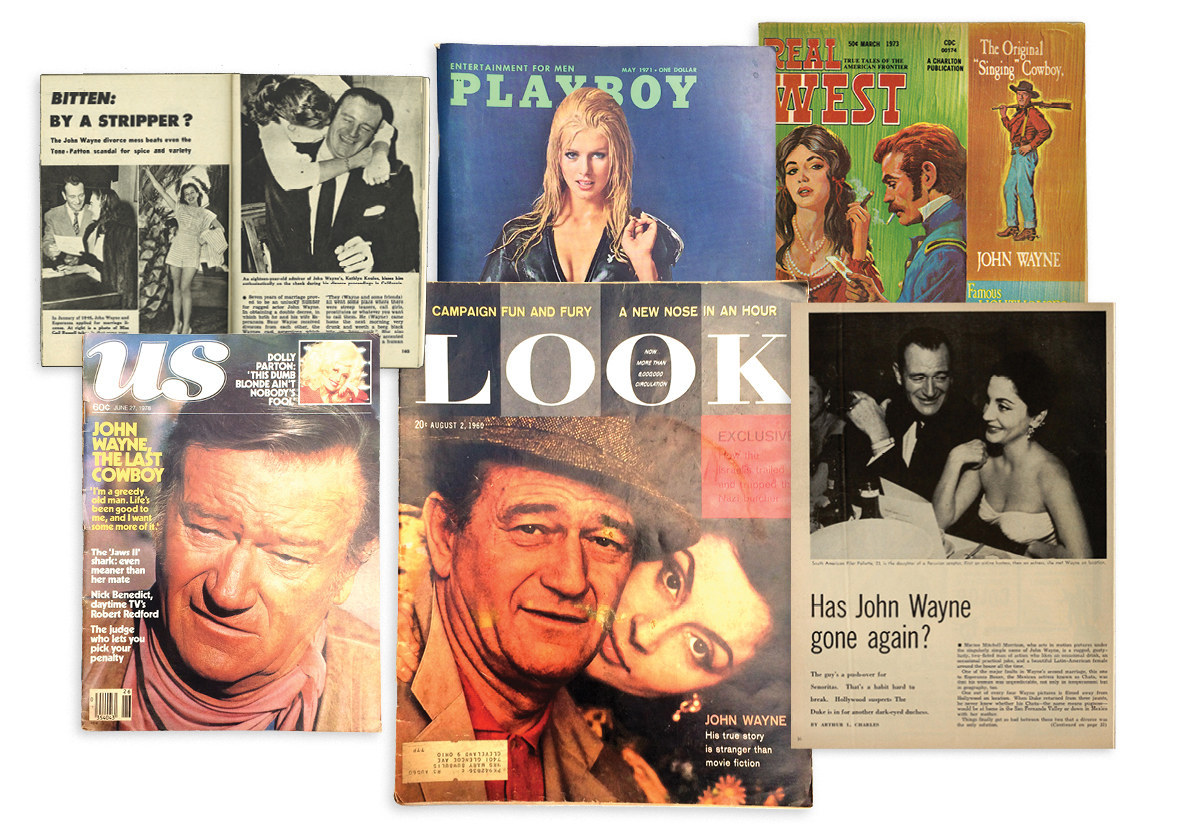

In the early ‘40s, Wayne had separated from Saenz. He then engaged in a three-year affair with Marlene Dietrich — kept secret from the reading public — before marrying his second wife, Esperanza, aka “Chata,” in 1946. When that marriage fell apart, it was figured as a natural result of Wayne’s masculinity. He wasn’t “the country club type,” and thus couldn’t deal with Chata’s social demands; he was just a “rugged, gusty, lusty, two-fisted man of action who likes an occasional drink, an occasional practical joke, and a beautiful Latin American female around the house all the time.”

The problem was that the current Latin American wife wasn’t fulfilling her domestic duties — which is why they were divorcing, and why Chata, infuriated and bitter, was alleging horrible things about the Duke in court: that he’d blackened her eye, pulled her from bed and beat her, given her multiple bruises, called her “obscene names,” and was “manhandling her in front of guests”; he “went some place where there were streep teasers [sic], call girls, prostitutes or whatever you want to call them,” she testified. “He came home the next morning very drunk and with a big black bite on his neck ... this was a human being bite.” Wayne’s lawyer countered that Chata was a drunk who “stayed out all night and returned with grass stains on her clothes,” and, during their estrangement, “entertained a male guest at their residence” while Wayne was on set.

The divorce drama threatened to become a huge scandal. But Wayne forked over a substantial amount of alimony, the two settled, and his image remained unscathed. In part because allegations of domestic abuse weren’t yet taken seriously, but also because Wayne’s alleged actions were not out of line with his onscreen image, which had him regularly verbally abusing women and, if not giving them black eyes, then manhandling, throwing them over shoulders, and general putting them in their place when necessary.

But when Wayne quickly took up with a third “Latin” beauty — this one a Peruvian actress by the name of Pilar — the press was forced, and failed, to adequately explain why a paragon of whiteness wanted only nonwhite women. “Don’t ask why he goes for these Latin American babes,” one fan magazine author averred. “He’s Anglo-Saxon down to his very toes; you’d think he’d fall for some doll from Iowa. He just doesn’t. Soon as a girl has blonde hair, his interest fades.”

When a detail of Wayne’s life didn’t fit his image, the myth simply assimilated it. That’s the thing about myths — once we become invested in them, we become adept at explaining, rationalizing, or forgetting any detail that doesn’t fit. It doesn’t matter if it’s a dodge of military service, treating women with the opposite of Western chivalry, or a generalized ambivalence toward horses, rustic living, or other fundamentals of Western life. As the weight of a myth grows larger, it grows increasingly difficult for any fact, quote, or anecdote to slow its roll.

Which pretty much explains what happened for the rest of Wayne’s career: If his ‘50s image was a wagon trail, then he spent the next 20 years retreading it, making the ruts ever deeper. Ideologies inherent to his image became explicit: There was his four-year presidency of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals, ultimately responsible for the blacklisting of members of Hollywood who refused to “name names” of suspected communists; his friendship with the increasingly conservative gossip columnist Hedda Hopper; his obsession with producing a massive, white-savior production of The Alamo; his membership in the far-right John Birch Society; and, as the ‘60s drew to a close, his attitude toward the conflict in Vietnam, which was so uncompromising and public that cultural critic Eric Bentley credited it with starting the war.

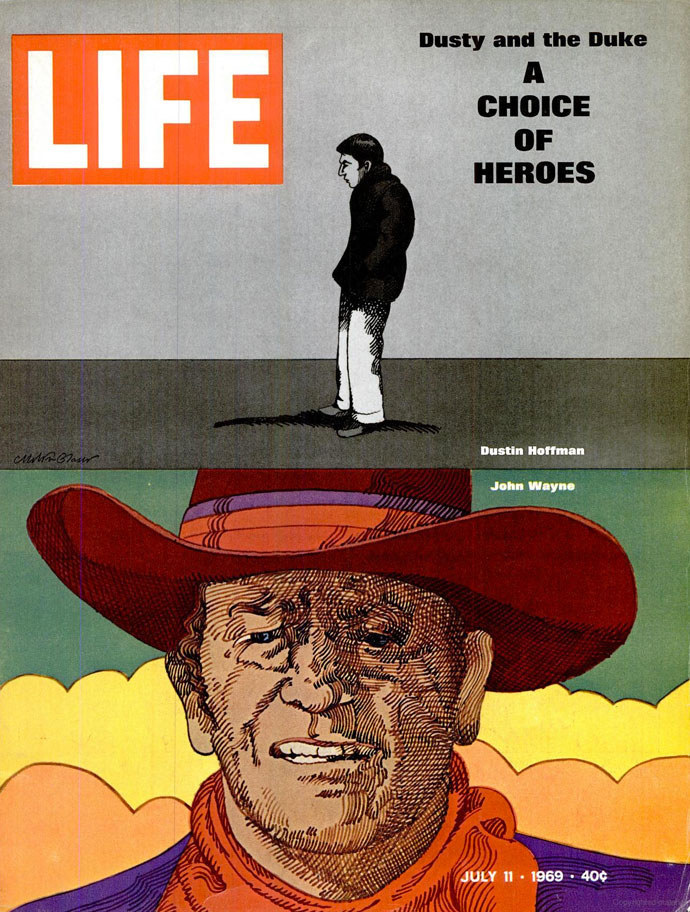

That attitude was underlined in a 1969 Life magazine feature contrasting Wayne with liberal Dustin Hoffman. The cover, in which a miniature of Hoffman’s sullen, black-and-white figure is rendered upon a crudely Technicolor Wayne, puts a fine point on the contrast: “a choice of heroes.” Inside, photographer John Dominus broke down the Wayne mythos in a way that, at least in popular magazine, felt unprecedented:

You can almost feel the movie world that Wayne lives in reinforcing his personal and political philosophy. On a movie set, if you don’t want that hill over there, you bulldoze it down. If there’s war to be won, you win it. It’s easy. And Wayne has been playing this kind of action hero for so long — he’s won so many wars and shoot outs and fistfights in Western streets — that he has become the character he has played so often. Don’t get me wrong, that makes him a damn attractive man. I suppose I was intellectually attracted more to Hoffman. But if I were getting up a poker game or fishing trip to Canada, I’d pick Duke.

Joan Didion, writing for the Saturday Evening Post in 1965, felt similarly about his movie star sway: “When John Wayne rode through my childhood, and very probably through yours, he determined forever the shape of certain of our dreams.” Her interactions with him are distinctly off-brand: He asks the waitress for “some Pouilly-Fuissé for the rest of the table and some red Bordeaux for the Duke.” But Didion nevertheless admits that his face is more familiar, more essential, than that of her husband.

Wayne’s politics might have been alienating to the left, but they produced a soft alienation, easily surmountable by the warmth associated with an image that seemed to have been with you all along. Those feelings were encapsulated in his turn as Rooster Cogburn in True Grit, in which Wayne is more gruff and irascible and inexplicably lovable than ever before. Which is part of why the performance won him his first, and only, Oscar — the same year that Hoffman’s Midnight Cowboy became the first, and only, X-rated film to win Best Picture.

When the left collapsed in the early ‘70s amid the ascendency of the moral majority and the conservative movement, it was as if Wayne had been right all along. Which is part of why, when Wayne vented his frustrations — and bigoted beliefs concerning black and Native Americans — in a 1971 Playboy interview, the only significant ripples were among the black press. If you’d been paying attention to Wayne’s movies, after all, you’d have seen all of those beliefs sublimated in one form or another.

Which is what led the Harvard Lampoon to award Wayne the “Brass Balls” award, calling him “the biggest fraud in history,” and issuing a challenge for him to appear in public. To the surprise of all, Wayne opted to accept the award, arriving in Harvard Square on a military tank amid a light snowball pummeling. Protesters yelled “Fascist Pig!” and “Eat shit, you racist!”; picketers from the American Indian Movement asked “Why Support Indian Killer John Wayne?”

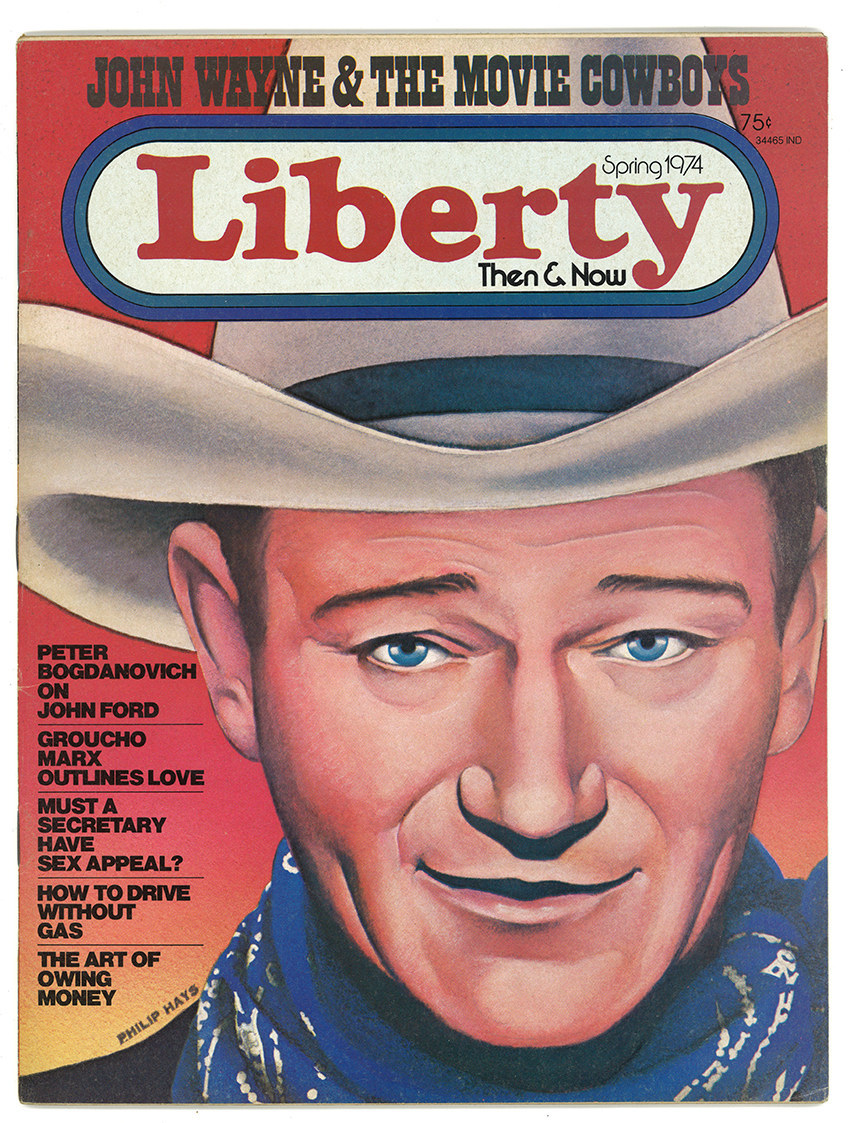

And while Wayne, who was ostensibly promoting his upcoming movie McQ, received a traditional Lampoon roasting — including jabs at his weight, his toupee, and his politics — the reception was overarchingly jovial, even positive. Multiple members of the Lampoon admitted to warming to him; during the roast, a member of the crowd yelled “I don’t care what they say, Duke, you’re still a man!” For the Harvard crowd and so many across America, Wayne may have been a bigot — but he was nonetheless “so much a part of the American folklore,” as Liberty magazine asserted in 1974, “that to reject him is to reject the American Dream.”

When Wayne died in 1979, at the age of 72, whatever part of him that had yet to be mythologized started to settle into stone. Sure, he succumbed to cancer, but not before overcoming it once (back in 1964, when he publicly declared “I beat the Big C”), undergoing open heart surgery, and telling Us Magazine, “I guess I’m just too goddamned tough to die.”

In Wayne’s final film, The Shootist, released in 1976, an aging, cancer-addled cowboy, disillusioned with the decline of the West, sets up a way for himself to die in a shoot-out — only to be fatally, shamefully, shot in the back. Look closely at the film, and you might sense something like ambivalence on Wayne’s part: The idea that no one gets to go on their own terms, or that the world — of the film, or real life — had ceased to abide by the codes the “last cowboy” held dear. If even a principled man could be shot in the back, well, then, it might be time for Wayne to take his leave as well.

In truth, Wayne’s roles, and personal ideologies, were much more ambivalent, complicated, and nuanced in his opinions than popular memory allows. But his death occasioned a swift and steady flattening of his image. What the lengthy obituaries began, Ronald Reagan, a friend of Wayne’s dating back to ‘30s Hollywood and a longtime political compatriot, completed, composing “The Unforgettable John Wayne” in the pages of Reader’s Digest. The piece, published in the heat of Reagan’s first presidential campaign, is ostensibly a eulogy. But it doubles as a brilliant bit of political stratagem: Speaking of the unflagging patriotism that drove Wayne to make The Green Berets, Reagan explained, “the public jammed theaters” to see it, despite round abuse from the critics.

The New Yorker utterly condemned the man who made the film. The New York Times called it ‘unspeakable . . . rotten . . . stupid.’ Yet Duke was undaunted. "That little clique back there in the East has taken great personal satisfaction reviewing my politics instead of my pictures," he often said. "But one day those doctrinaire liberals will wake up to find the pendulum has swung the other way."

If that pendulum began its path with the election of Nixon, it reached its endpoint with Reagan’s election, just a month after the publication of the piece. Reagan claimed that Wayne was “more than an actor.” Instead, “he was a force around which films were made.” A force, which is just a way of saying an idea with heft: something that pushed, rather than simply suggested, that you get on its side.

In truth, Reagan wasn’t much different. While his movie career had never amounted to much — unlike Wayne, he’d enlisted during World War II and thus derailed whatever momentum he’d accumulated — they’d both hitched their images to an ambiguous idea of a return to simple American values, to when a man could be a man, when business could be unregulated, when a man who worked hard didn’t have to give his money away to things that didn’t match his principles.

Back in 1968, Wayne denied rumors that he’d run as George Wallace’s running mate: He never fancied himself a politician, just an ideologue. But Reagan’s election extended Duke’s legacy: There’d be a movie star, with Western-style ideals, ruling America. It just wouldn’t be Wayne.

Reaganism, with its Wayne-inflected ethos, would dominate American politics and culture for over a decade. But in order for that to happen, the Wayne narrative had to become as pat and palatable as possible. The same year as Reagan’s eulogy, a 98-page collector’s edition magazine dedicated to Wayne established Christianity as a pillar of his image, including a piece, ostensibly authored by Wayne, that reads like an evangelical sermon. “I’m not a preacher, but I can tell you one thing: there is a God. . . Let Him be the co-pilot of your mind, your body, your soul, your spirit. I’m glad I did.” It spends pages suggesting that Wayne had been turned down not only by the Navy, but all four military branches, and had spent the rest of the war tirelessly aiding veterans. Deeper in the magazine, a feature on Wayne’s women neatly explains his second marriage: “Their domestic quarrels made headlines. Wayne hated that. Their court battle made more headlines. Wayne needed only one thing — to wash the woman out of his hair.” But “with that trusty Winchester in his hands, and fighting the baddies, he could forget his misery.”

And then there were the Wayne superlatives: “He was, without doubt, the fastest gun in the West.” And: “As he smooches, touches, kicks and shoves, the ladies melt and swoon and willingly, giddily became his slave.” Or: “No man ever sat more magnificently on a horse, rifle poised for action, than John Wayne.”

It’s the sort of bombast that Wayne, no matter his faults or politics, never would’ve said in person — but that would be increasingly attributed to him. To survive, after all, myths have to make themselves malleable to the tenor of the times; today, it’s most palpable at the birthplace museum.

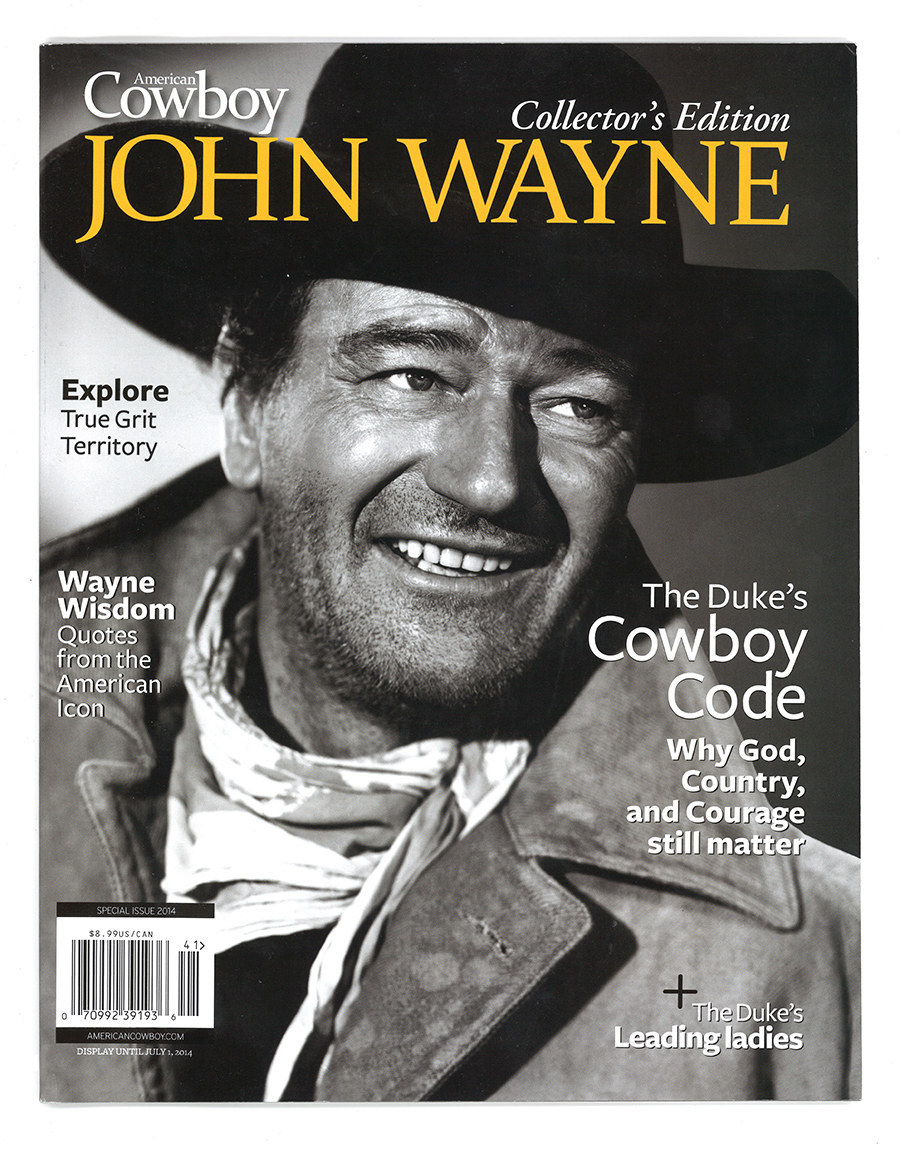

The museum’s director attributes much of the museum’s success to its proximity to the interstate, but it’s more than that. It’s the same thing that sells American Cowboy’s John Wayne issue for $8.99, filled with advertisements for Winchester rifles, “iconic hats made for an iconic American,” and John Wayne’s Monument Valley Ride, a “historic old West horseback ride” in Arizona from an outfit called “Great American Adventures.” It allows Mike Enzi, a Republican senator from Wyoming, to craft an essay on preserving the “Cowboy Code of Ethics,” and Lew Sterrett, founder of a “Christian-based equine-illustrated leadership training ministry,” to extrapolate on Wayne’s image and the primacy of faith. “I do not know of Wayne’s personal faith in his salvation through Jesus Christ with any certainty,” Sterrett writes. “But I do believe he would advise us to man up — the sooner, the better — and to set the compass on the true course.”

The Western has long operated in cycles, and each time it resurfaces, it’s shaped to address a new set of fears: the brutally violent and nihilistic Westerns post-Vietnam, the gender politics of Unforgiven in 1992, even the veteran’s struggles central to the rebooted 3:10 to Yuma in 2007. Wayne is the Western star, but he’s also his own particular subgenre, used to staunch a particular set of masculine anxieties, whether in 1948, when post-war masculinity, and the desire for a certain sort of gruff authority, launched him to stardom, or the late ‘60s, with the hunger for the moral legibility amid a muddled war, or even in his comments to Playboy, which simply ventriloquized principles that many, even a nation supposedly in the throes of the civil rights movement, still believed.

At any point in the 75 years since Wayne came to Hollywood, to say “I love John Wayne” could mean an assortment of things: that you loved Westerns, that you found older, principled men sexy, that you were a racist or a xenophobe or that you simply yearned for a time when things seemed simpler, when the road to righteous living seemed clearer. To love the West is to love fresh air and open spaces, but to love John Wayne, and the West he embodies, is to embrace the promise of the American dream and excuse the darkness and history of exploitation that seeps beneath it.

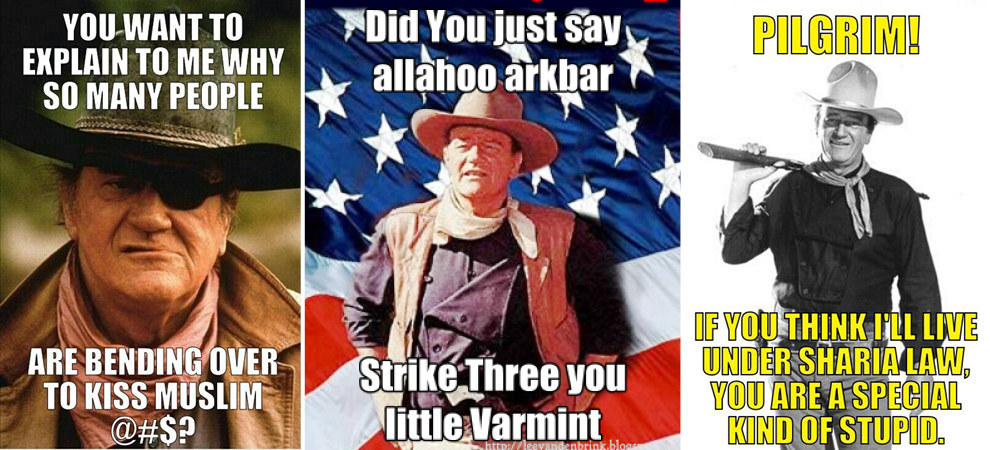

Wayne’s image acts out fears about the death of the West — which is to say, the death of America — but it also enacts a triumph over them. Which is part of why it’s so readily wielded today against the primary source of white, Christian, American anxiety: the seeming spread and threat of Islam.

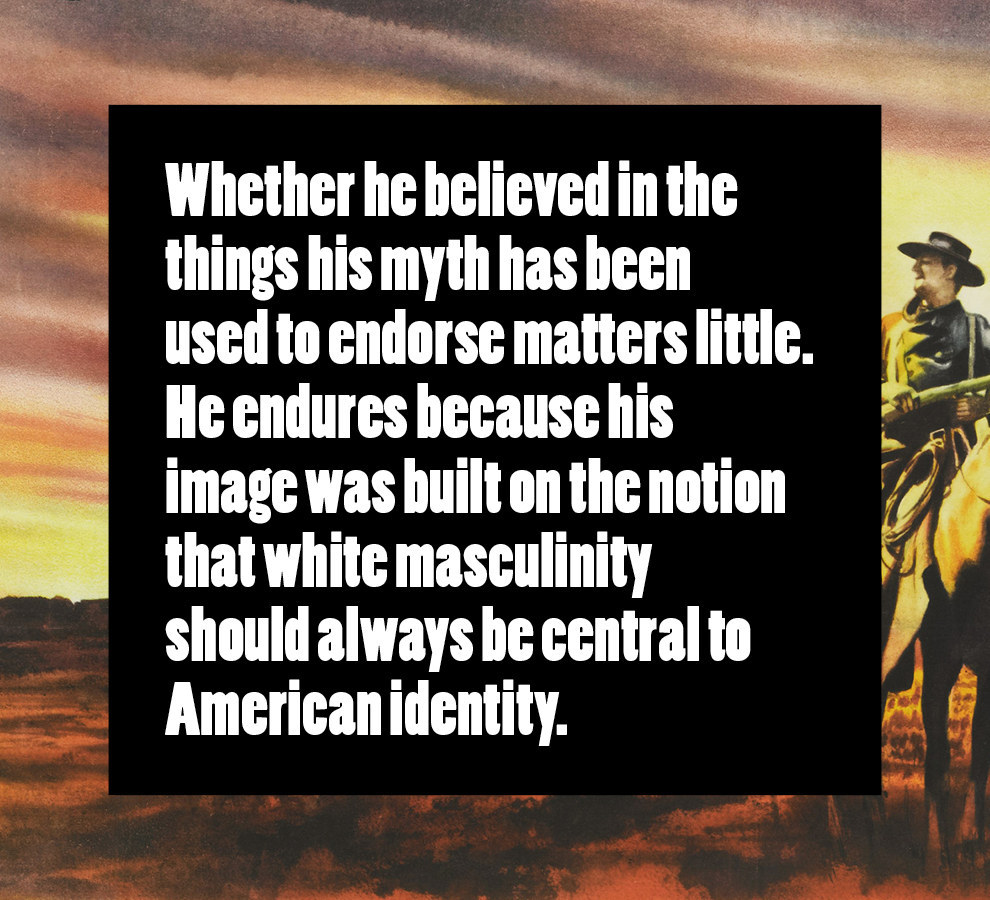

And whether Wayne, the individual, believed in the things that his myth has been used to endorse ultimately matters little. Wayne endures because that image, like that of America, was built on the notion that white masculinity should always be central to American identity. And he will continue to endure as the defenders of white masculinity continue to seek ways to express their horror that that is increasingly, and irrefutably, no longer the case. Marion Morrison may be dead. But it’s essential to remember where, and why, this newly meaningful version of John Wayne so vividly lives.

In the final exhibit at the Wayne museum, there’s a framed letter from President George W. Bush, sent to commemorate Wayne’s 100th birthday. “Our nation’s past is filled with wonderful stories of Americans who embodied the values of courage, duty, and patriotism,” he wrote. “This event is an opportunity to celebrate the life and career of an American icon who holds a cherished place in our Nation’s heart.”

I walk out the door, past the quiet blocks of beautifully preserved houses, and the yard signs with "Donald Trump: Make America Great Again." I get in my Jeep Liberty, and I drive toward Omaha — due west.

The author would like to thank the University of Idaho's Dr. Russell Meeuf for his assistance with this piece.

Also read:

The Showdown Over Billy the Kid