To talk about Jennifer Lawrence is to talk about the qualities our society values and privileges: chill, blondeness, charisma. Then there’s her savvy: how she’s managed to shine through two increasingly limp franchises, and how, in between those films, she’s chosen roles that have stretched her, or, at the very least, figured out a way to allow America to love her. In five years, she’s earned three Oscar nominations, including one win. Serena — the effectively straight-to-VOD film from March of this year, co-starring Bradley Cooper — has been effectively excised from Lawrence’s narrative. Because what we don’t talk about when we talk about Lawrence, at least up to this point, is failure.

Her latest, Joy, has all the markers of continuing her legacy: a big, weird, meaty part that allowed her to look great (short skirts, leather jackets) and act loudly. It’s her third film with David O. Russell, the director who, with Silver Linings Playbook and American Hustle, first amplified what now feels like the most essential of J.Law characteristics: the vulnerability, the brassiness, the arresting, if somewhat untraditional, beauty.

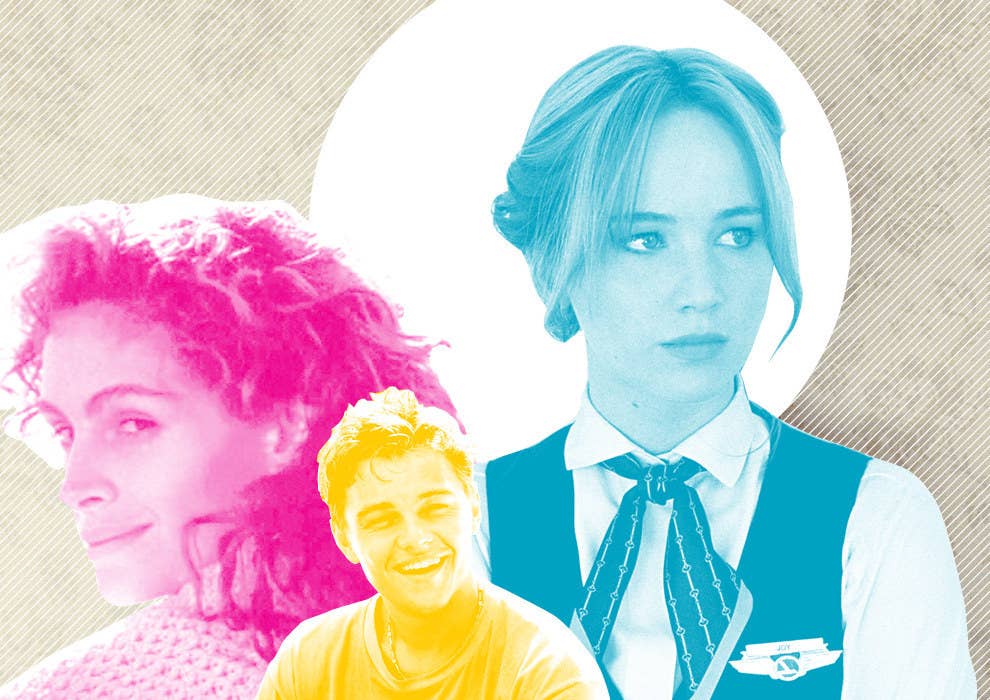

Joy suffers from a general mishmash of tone, a misinterpretation of the melodramatic mode, Russell’s profound misunderstanding of the “powerful women” on whom the film is supposedly based. What emerges from the wreckage, however, is Lawrence’s performance. The way critics have been talking about it recalls the rhetoric that accompanied similar missteps by Julia Roberts and Leonardo DiCaprio, the two stars in the last 30 years whose early careers and charisma most rival Lawrence’s. All three were flung into the upper echelons of fame before the age of 25, heralded as blockbuster stars who could act. But it took bad films to see just how good Roberts and DiCaprio were, and it’s taken a movie as mediocre as Joy to understand the same of Lawrence — and how infrequently a star of her wattage comes along.

There was a period of time during the spring of 2013, when it felt like everything Jennifer Lawrence touched — every interview, every role, every gown, every mug for the camera — made you like her more. That’s what it felt like in 1991 with Julia Roberts.

There was that hair, and that smile, and that coltish way of maneuvering the world. She was infectious, irresistible — people today make fun of her laugh and assertiveness, but back then, she made every other female star of her age look like an amateur. “It is not so much her cascading hair or even her take-no-prisoners smile that makes her such a potent cinematic force. Rather, in the tradition of screen idols since the dawn of time, she manages to seem more alive than life itself,” critic Kenneth Turan wrote in 1991.

The first glimmers of that vitality were visible in 1988’s Mystic Pizza, a tiny film that attracted a massive following, thanks to Roberts’ performance. She then took over a role intended for Meg Ryan in 1989’s Steel Magnolias, where she found herself surrounded by powerhouse names — Sally Field, Dolly Parton, and Olympia Dukakis — and managed to make her performance the central gravity of the film. She was nominated for an Oscar, and won a Golden Globe.

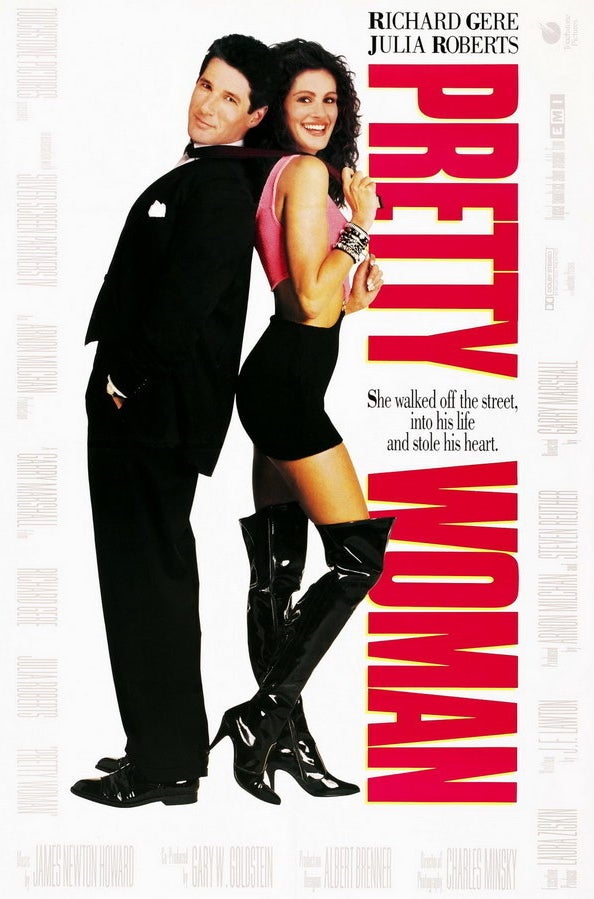

And then there was Pretty Woman in 1990: a trifle of a Cinderella adaptation that so effectively encapsulated the burgeoning and highly seductive ideologies of post-feminism that it, along with some excellent costume design, transformed Roberts into something more like a cultural icon. There are few scenes more emblematic of the ‘90s than Roberts on the poster for that movie — or another image, later in the film, in which she waits, white-gloved, for her prince to bejewel her. It made sense when Joel Schumacher, who directed her in Flatliners, declared her “the hottest, most exciting female star in movies since Marilyn Monroe” — the last female star to so seamlessly combine the whore and virgin.

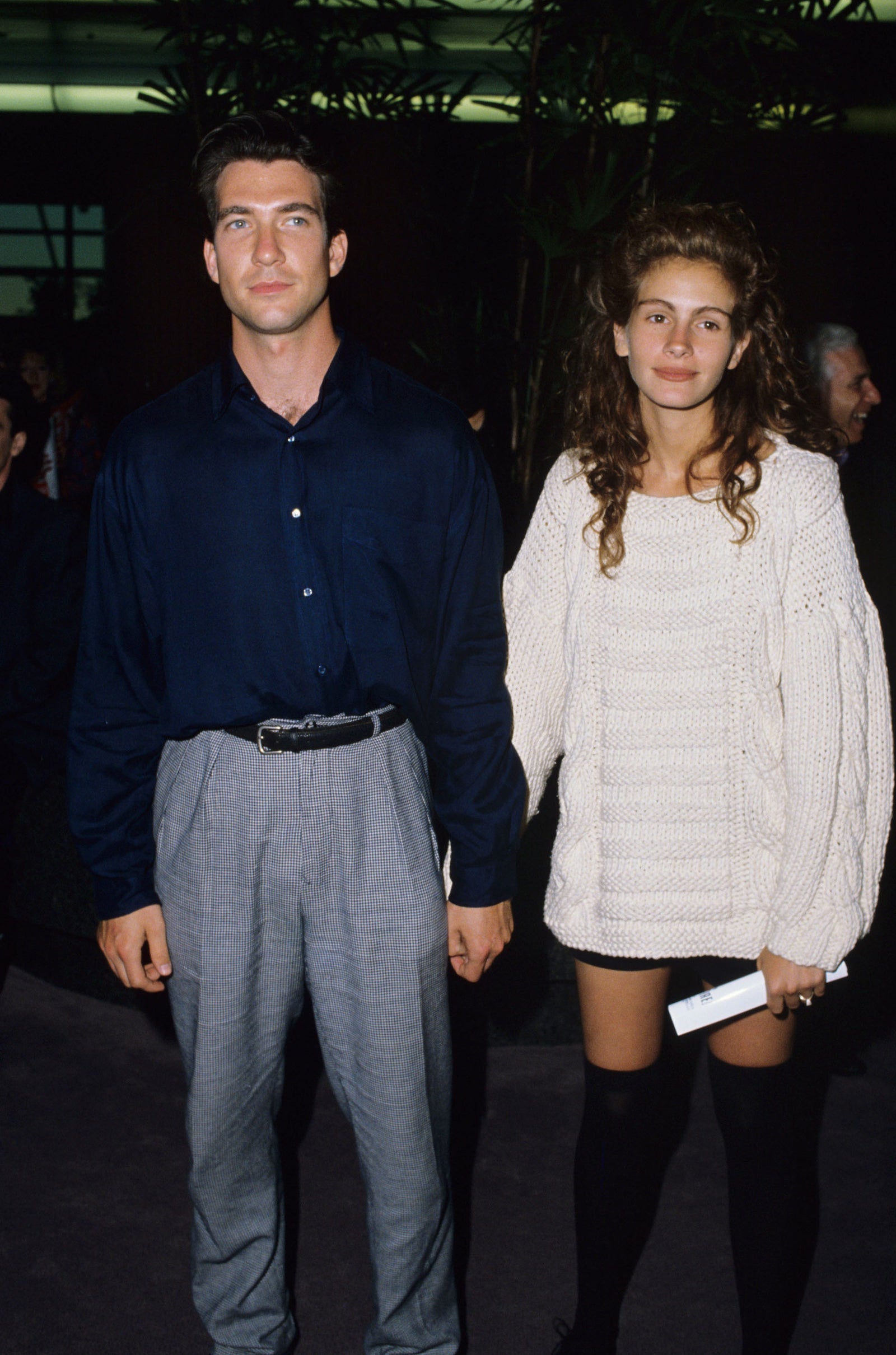

Roberts was nominated for a second Oscar for Pretty Woman and, with the success of the 1991 hacky genre film Sleeping With the Enemy, became the most bankable female star — the only female star who could “open” a film. The movies were middling at best, but there was a hunger for her, to see what she did next, both onscreen and off. And part of that desire stemmed from her personal life, which involved a stream of on-set romances: first with Liam Neeson, then with Steel Magnolias co-star Dylan McDermott, who was briefly her fiancé — at least until she met Kiefer Sutherland on the set of Flatliners.

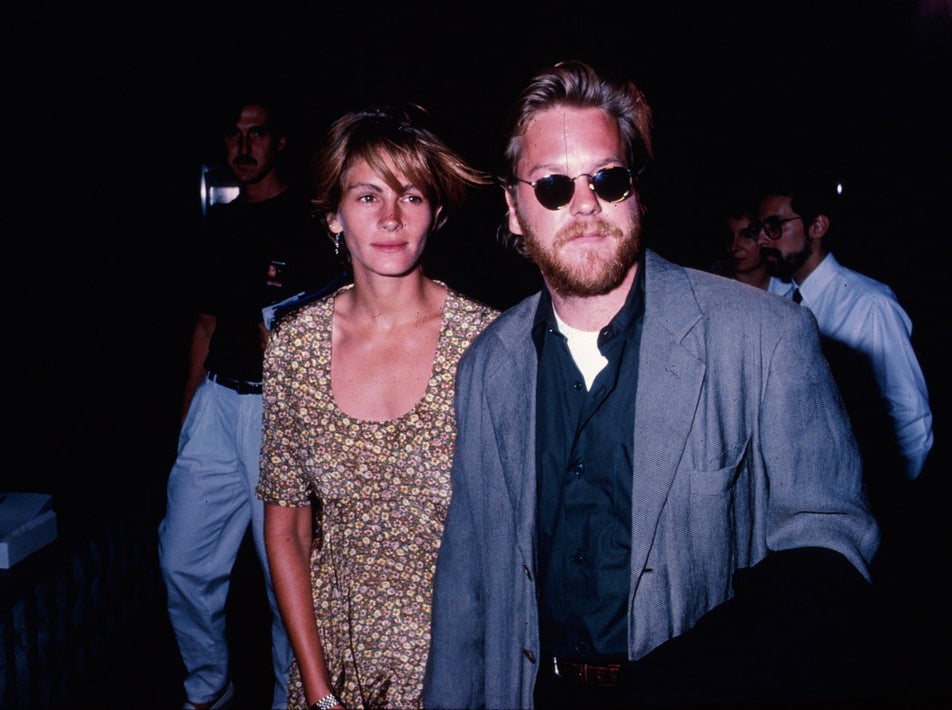

The son of ‘70s film star Donald Sutherland, Kiefer was like Hollywood royalty. He was also young, handsome, something of a bad boy — a fitting counter to Roberts’ Southern naïveté. He proposed, and the gossip mags went crazy over elaborate plans for a wedding slated to take place on the backlot of Fox Studios, which was to be made up to resemble “a gardenlike paradise.” The bridesmaids, People reported, were to wear $425 dyed-to-match seafoam green Manolo Blahniks.

But then Roberts called off the wedding four days before, absconding to Ireland with actor Jason Patric — a former friend of Sutherland’s. “Julia is very much Miss Tinkerbell romantic,” a “friend” of Sutherland’s told People. “One minute she’s in love with this guy, the next in love with another.” It was a classic jilting, and the gossip press took hold, alternating between blaming bad boy Sutherland (who was caught with a go-go dancer the following week) and the “ice princess” Roberts.

Roberts and fiancé Dylan McDermott; Roberts and fiancé Kiefer Sutherland.

That was still the conversation floating around Roberts when Dying Young, a classic weepie of the Fault in Our Stars variety, hit theaters in May 1991. It had all the signs of a hit: Roberts on the marquee, Schumacher directing, and a sweeping love story. But it was also wane and implausible, and critics insisted on dubbing it a flop, even as it grossed $80 million worldwide on a reported $20 million budget.

But the blandness of Young made it all the easier to see what made Roberts different from her contemporaries — and similar to the massive stars of the past. She’s the sort of character that, in the words of the New York Times’ Caryn James, “women liked and wanted to be, and that men liked and wanted to have.” Or, as Janet Maslin put it:

It takes a special kind of person to embark on a two-week road trip, find a charming cottage in a romantic coastal town, set up housekeeping, make a set of new friends and show up at a Christmas party in a strapless white evening gown, something that could neither have been packed nor purchased by any reasonable means. To do this takes a movie star of the old school, the kind whose overriding personality is never fettered by the specifics of a given role. Julia Roberts is that kind of star, and she gets away with murder in stories that nobody else could make nearly so disarming, stories that become Julia Roberts movies no matter who else happens to be on hand.

That sort of automatic belief, and the loyalty that attends it, is impossible to produce. It cannot be earned. It simply is. It’s also foundational to charisma, which can be dampened by a bad script and mannered directing, but doesn’t disappear. And while an abundance of charisma is rarely enough to transform a bad movie into a good one, in Dying Young, it made space for critics to formally recognize that she wasn’t just a happy coincidence of roles and gossip, but something more than the sum of her beautiful parts.

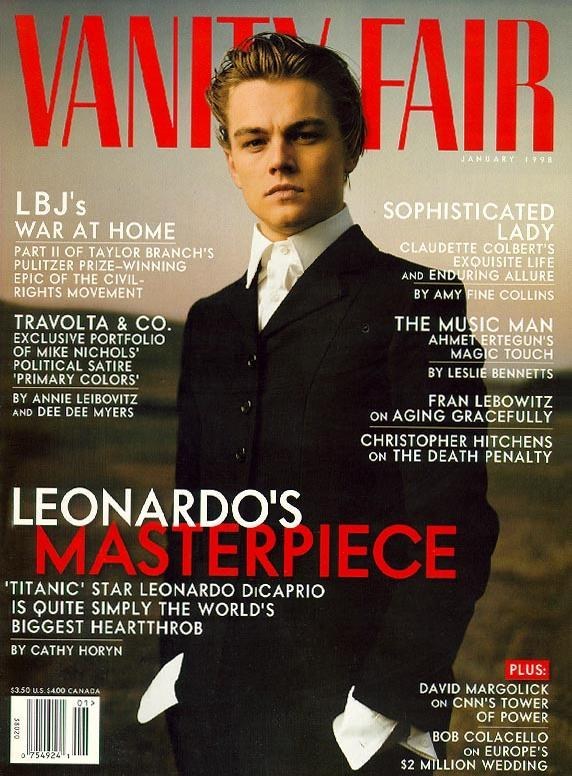

“Ask the top talent agents or studio executives or producers for the name of the biggest star in town,” New York Times reporter Bernard Weinraub wrote in 1998. “It’s not Tom Cruise or Mel Gibson or Harrison Ford. The answer is one word: Leo.”

At that point, DiCaprio was still trying to escape the massive wake of Titanic, a film that grossed more than $2 billion worldwide and, in one three-hour span, established DiCaprio as an object of global desire. With What’s Eating Gilbert Grape and This Boy’s Life in 1993, and The Basketball Diaries and Total Eclipse in 1995, DiCaprio offered a convincing counterargument to what one would expect of a face like his. And then there was 1996’s Romeo and Juliet — a film that managed to make DiCaprio feel like a live wire and the most beautiful thing you’d ever seen onscreen.

But it was Titanic in 1997 that made it effectively impossible for DiCaprio to do anything (walk across the street, release a major movie) without attracting massive (mostly female) attention. So he appeared in a forgettable historical picture (1998’s Man in the Iron Mask) and made a self-mocking cameo in Celebrity that same year. He hopped from party to party with his now-renowned “pussy posse,” a “mandolescent” who, according to one New York Times profile, would ask supermodels, “Do you know who I am?” He was wasted, a parody of a hot guy in his backward baseball cap and sweaty T-shirts, and would have been a caricature of himself if it all didn’t somehow still feel so very compelling. Think recent Bieber, but with talent that allowed you to make more excuses for his revelry.

During these peak pussy posse years, the consensus was that DiCaprio had the same combination of skill and bankability that had distinguished Roberts less than a decade before. But it took Danny Boyle’s The Beach — DiCaprio's much-anticipated return to the screen in 2000 after two years away, and an overproduced, beautiful dud — for people to articulate it. “All of Mr. DiCaprio’s charisma and the director’s savvy are used to divert us from the fact that there’s nothing much going on,” wrote Elvis Mitchell, in a tone that would characterize the majority of reviews. But those accolades didn’t reach critical mass until he showed up in a bad film — the same for his “shrewdness,” according to the Globe and Mail, in avoiding “testosterone-heavy action films” while accepting those “meaty enough to avoid seeing him labeled as this generation’s Troy Donahue or David Cassidy.”

The same sentiment consolidated in the publicity for the months preceding the 2002 one-two Christmas-punch of Gangs of New York and Catch Me If You Can. “With Leonardo DiCaprio it’s charisma, pure and simple, and if you can define what charisma is, tell me and I’ll bottle it,” Fox 2000 President Laura Ziskin told the Times. Or, as Baz Luhrmann put it, after Titanic, DiCaprio “became global culture, in much the same way as The Beatles or Elvis. I’ve been in mud huts in Egypt and seen two posters on the wall: Leonardo and Michael Jackson. You know 'Titanic' is 'Romeo and Juliet.'" Those two films made Leonardo the tragic romantic icon of his generation.”

Take a look at DiCaprio’s career after this point and you’ll see the wages of that understanding. The middling success of The Beach mattered not at all: As it hit theaters, he was already working with Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg, the two poles of the contemporary American film establishment, and quickly signed on to 2004’s The Aviator — making him the first star since Robert De Niro with whom Scorsese wanted to work on a longer-term, collaborative basis. He’d spend the next decade moving up and down the critical and marketable spectrum: Scorsese after Scorsese, with intermittent pauses for Edward Zwick, Ridley Scott, Luhrmann, and a re-pairing with Kate Winslet in 2008’s Revolutionary Road. No one — not even Brad Pitt or George Clooney — has enjoyed his track record in terms of consistent critical acclaim and box office success.

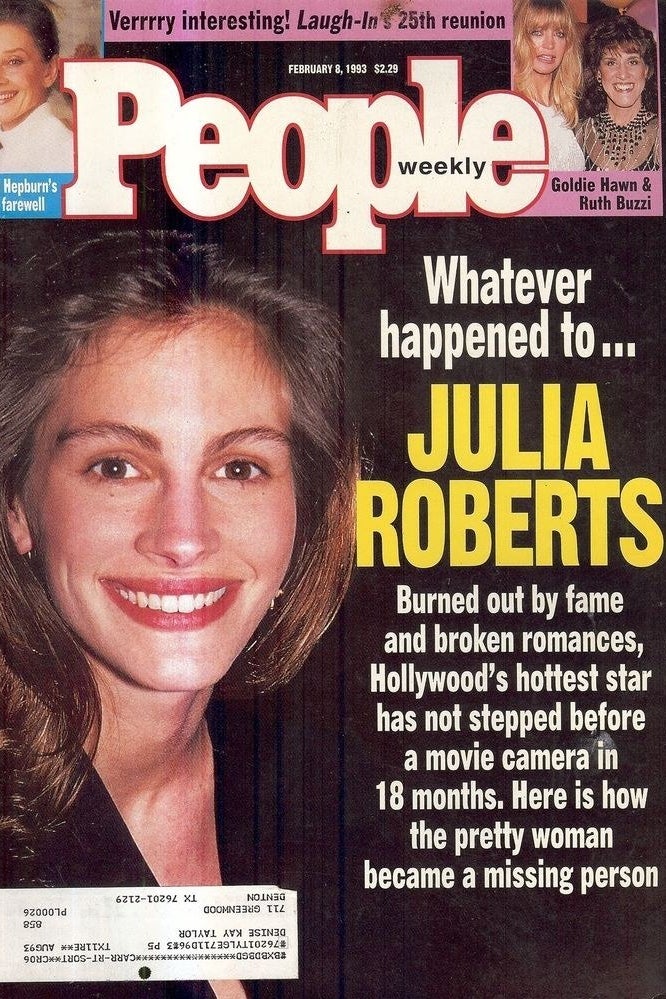

Bad films helped solidify both Roberts and DiCaprio as stars without rival, but what happened afterward, has, in many ways, differentiated their legacies. Roberts reacted to her status, and the resultant fixation on the broken fairy tale details of her personal life, as a shock to the system. “People talk about this Julia Roberts almost like it’s a thing, almost like it’s a cup of Pepsi,” she said in 1993, after her wedding to Lyle Lovett. “People think Julia Roberts is something they created. The fact is, 26 years ago there was this scrunched up little pink baby named Julia Roberts ... I am a girl, just like anybody else.”

DiCaprio responded to the same scrutiny by giving it the finger, sometimes literally, but mostly figuratively: more girls, more clubs, but never scandal — in part because he was a man, and male stars are given a pass when it comes to living their private lives loudly. Instead of reminding the press he was a person, he shrugged and referred to the press as a “monster you have no control over.” “I was absolutely shocked at how much people [in the press] lie,” he told the Globe and Mail in 2000. “It was a huge learning process for me after Titanic. But I did not want to become a hermit. I needed to live my own life and do whatever the hell I wanted to do.”

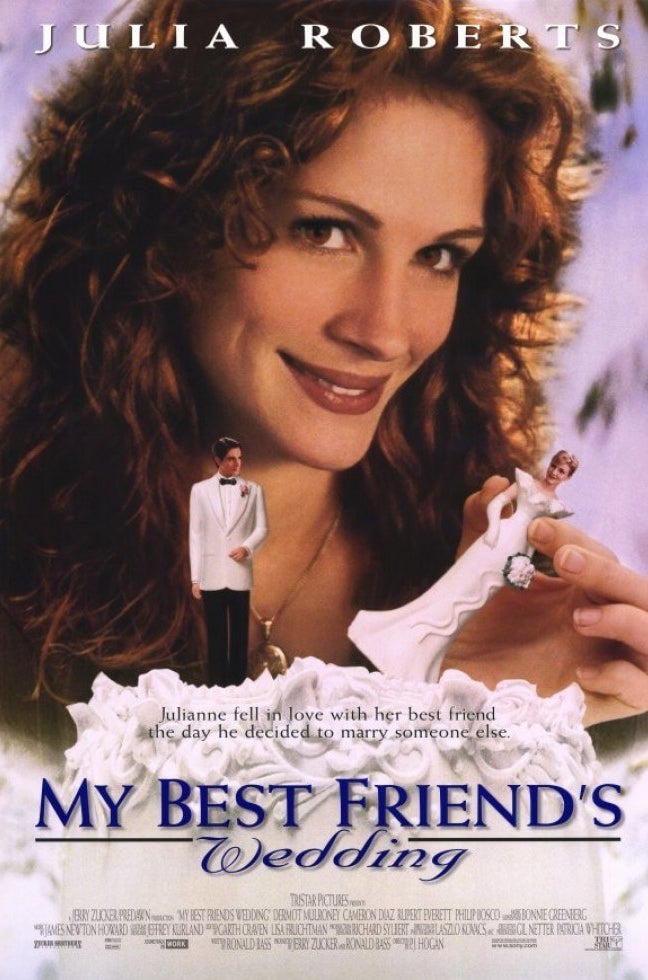

There were differences, too, in what audiences would allow of each star onscreen. As Turan noted of Roberts back in 1991, “Her range is not the broadest, but she is peerless within it.” When Roberts stepped out of that range, she was scolded: ridiculed for daring to make herself unattractive in 1996’s Mary Reilly, or for attempting an Irish accent that same year in Michael Collins. When she returned to form in 1997’s My Best Friend’s Wedding, she pleaded with her fans: “My hair is a lovely shade of red and very long and curly the way you guys like it — please see this movie!”

Roberts returns to Pretty Woman form in My Best Friend's Wedding and Erin Brockovich.

It was only through that return to form — and the slew of similarly typed movies that followed, including 2000’s Erin Brockovich, in which she played a alternative-universe version of her Pretty Woman character, that she was able to become the first woman to join the $20 million paycheck club. DiCaprio, of course, had been there since 1998.

Since then, Roberts’ roles have been safe, predictable, and, increasingly, child-oriented. She remains a massive star — but the repetition of performing Julia Roberts, or the labor of her own charisma, has dimmed.

DiCaprio, by contrast, has become Scorsese’s new muse. He’s worked with all the great (male) directors of contemporary cinema. Even his notable misstep (Clint Eastwood’s J. Edgar in 2011) still made money. He’s been nominated for five Oscars and 11 Golden Globes. He’s cycled through supermodel girlfriends; his pussy posse remains intact. He’s pursued causes, like environmentalism, that are important to him. He’s interviewed presidents. He bloats out, revels in his dadbod, grows unbecoming facial hair, and still manages to handsome himself up when the need arises. He’s taken seriously — something that Roberts, for all of her power, and all of the similar rhetoric used to describe her unique qualities, has never truly enjoyed.

While Lawrence’s trajectory shares several qualities with both Roberts’ and DiCaprio’s — the indie star, the breakthrough, the talk of charisma, and, most recently, the bad movie — she’s also synthesized much of what made Roberts irresistible and the attitude that made DiCaprio seem invincible. Like DiCaprio, she’s sought out auteur directors (Russell and, soon, Spielberg and Darren Aronofsky) to balance out her more commercial roles. When scandal hit in the form of a very public airing of nude pictures hacked from her iCloud account, she stayed silent before a calculated, pointed response. “Just because I’m a public figure, just because I’m an actress, does not mean that I asked for this,” she told Vanity Fair. “It does not mean that it comes with the territory. It’s my body, and it should be my choice ... Anybody who looked at those pictures, you’re perpetuating a sexual offense. You should cower with shame.”

She kept her relationship with Chris Martin nearly invisible; she speaks frankly about sex and her vagina. When she gets in a fight with a director, it’s not her that’s framed as difficult; when the Sony hack revealed a discrepancy in pay between her and her male American Hustle co-stars, she wrote publicly about it. Lawrence emanates a sense of ultimate control, even as she admits, as she did this past fall, that “I’m just a girl who wants you to be nice to me” — words that bear an uncanny similarity to Roberts’ own comments at a similar point in her fame.

“I don’t think there’s any actor who has more power in terms of box office,” Hunger Games producer Nina Jacobson told Vogue. “I would be hard-pressed to think of anybody who has the freedom of choice she has.” With Lawrence’s work with Russell, The Hunger Games and X-Men behind her, she’s at the same place as was DiCaprio in 2002, when Catch Me If You Can and Gangs of New York were about to showcase just how perfectly he could conform to his existing image — and how effectively he could undercut it. “He has finished one arc,” Marshall Cella wrote in a massive New York Times Magazine profile of DiCaprio, “and is starting a fresh one.”

In this moment, Lawrence seems poised to do the same. But whether her trajectory will look more like Roberts’ or DiCaprio’s has less to do with talent and more to do with confidence — and a willingness to fortify the core of her uniquely irresistible image not by reproducing it, but mapping the far corners of her capabilities. That thing in her eyes, the thing that people can’t describe but always want to, the thing that makes you and your mom and your boyfriend all just like her, it’s not going anywhere. But in order to make it something that people will still be talking about 20 years from now — in order to be more like self-determined and self-preserving stars like Paul Newman, or DiCaprio, and less like, well, Roberts — she’ll need to go beyond what we know, today, as J. Law, starring in J. Law movies, making J. Law gaffes. It’s not a turning away from who she’s come to represent, but a willingness to transform herself into something even more.