Earlier this year, a woman named Tandra Barnfield posted a picture of herself and her wife kissing outside of the Duggar house — setting of the TLC show 19 Kids and Counting — as a protest against the family’s position on homosexuality. The picture went viral, prompting a reporter to contact Barnfield, who has family in the Duggars' hometown of Springdale, Arkansas. Barnfield simply reiterated the rumors that had been swirling around Springdale — and internet forums like Free Jinger — for years: Josh Duggar had been involved in some sort of sexual abuse, abuse that had been covered up by the family and TLC.

By the end of May, the Duggar family would be torn asunder, prompting Josh Duggar’s resignation from a conservative lobbying firm and a formal denouncement from presidential candidate Rick Santorum, and bringing the Duggars to the center of the national conversation. When Jim Bob and Michelle Duggar went to Fox News’ Megyn Kelly to defend their actions, the broadcast attracted 3.3 million viewers.

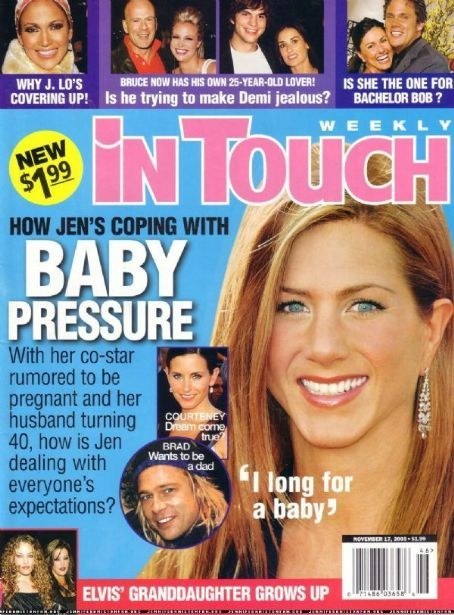

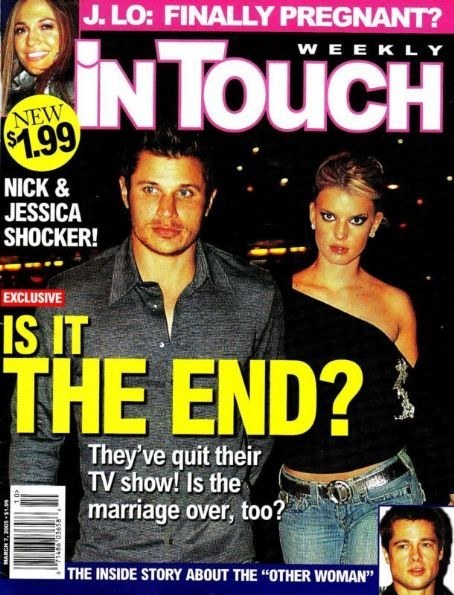

It’s not surprising that the Duggars or TLC attempted to cover up Josh’s behavior. The surprise is who broke the story: not a mainstream outlet like the New York Times or CNN, or a celebrity gossip site like TMZ, or even by the National Enquirer, which was deemed eligible to compete for a Pulitzer for its work on John Edwards in 2010. Instead, the story came from In Touch, a 13-year-old magazine that — among many other unfounded rumors and half-truths — has not only repeatedly declared the demise of Kim Kardashian and Kanye West’s marriage, but also suggested that Khloe Kardashian was, in fact, the daughter of O.J. Simpson. A gossip rag.

But recently, things have changed. Despite its credibility issues, In Touch is asserting its place in a long lineage of tabloids that have split their coverage between playful and suggestive covers and rigorous coverage of celebrities, unearthing the sort of material that publications like People and Us Weekly are too meek or too beholden to publicists to cover. Unlike their “personality journalism” competitors, tabloids have never scoffed at infuriating the celebrity apparatus. If celebrities already hate them, the logic goes, why not dig a little deeper and get the real dirt?

That same logic guides TMZ, which has publicly vowed never to bow to publicist demands, cover red carpets, or play by the accepted rules of the celebrity game. But TMZ simply took the tried-and-true tabloid practices and transplanted them online, dominating the field while competitors like the National Enquirer tried to figure out how to make a functioning website. In Touch’s Duggar scoop thus not only recalls the heyday of the print tabloid, but also highlights its willingness to immolate the celebrity apparatus.

As Elaine Lui, a longtime gossip columnist and observer of the industry, puts it, “In Touch was willing to go where others would not: The Duggars were regular guests on the Today show, never called out for their misogyny — even supposedly proper news journalists were backing off because of the fear of evangelical backlash, which just might be even more terrifying than Hollywood backlash. But In Touch just wasn’t afraid of that demo — or decided it was worth it to risk that demo’s wrath.”

Still, it's a curious time to double down on old-fashioned tabloid journalism. In Touch and the rest of the traditional tabloids have seen their circulation numbers plummet over the last five years. The Duggar stories may have increased web traffic to In Touch.com by 25%, but that’s 25% on a monthly average of 284,000 unique visitors — a sliver of People.com’s 26.7 million, or TMZ.com’s 23 million.

But the Duggar story was never intended to drive traffic. It was supposed to sell magazines, which has always been the In Touch strategy, with its bargain basement $2.99 price tag and its publisher’s established disinterest in accumulating subscriptions. Three weeks after the initial scoop, the Duggars are still on the cover of the magazine, and In Touch continues to chase the story, revealing the “10 things they’re still hiding” after the Fox interview and the full transcript of a 911 call to report the abuse.

In Touch has always been focused on “what the reader wants, not what they think the reader wants.” But does the Duggar scoop signal a potential revitalization of a magazine long in decline — or is it the last gasp of an old-fashioned print tabloid?

Over its 13 years on newsstands, In Touch has cultivated a mixed reputation. In the beginning, it vied for a slice of People Magazine's audience, building its circulation to 1.2 million in just four years, making it one of the fastest-growing weekly magazines in recent memory. But what started as a People clone, publishing a mix of sunny celebrity stories and tales of ordinary people doing extraordinary things, shifted course over the 2000s, establishing its identity through endless Kardashian covers, pregnancy “bump” speculations, and Brangelina breakup rumors. It became, in other words, a tabloid, with the corresponding willingness to narrativize facts in a way that pleased an audience hungry for celebrity entertainment, however implausible.

Tabloids have long been the place where hungry, aggressive reporters cut their teeth. As longtime Star Editor Stephen LeGrice told me, “Especially back in the day, the tabloids were filled with really crack reporters — people coming from local papers, or from Fleet Street in the U.K., with real skills. The only difference between what we did and what the mainstream papers did was the money.”

“The money,” of course, is what In Touch and the rest of the tabloids are willing to pay for tips, documents, and leads — a practice that’s frowned upon in mainstream American journalism circles, but an accepted and long-standing tradition in Europe, where the National Enquirer began poaching reporters from in the 1970s. Today, the National Enquirer homepage lures tipsters with the promise to EARN BIG BUCK$$$$!; In Touch’s “Hot Celebrity Tip Box” makes no mention of payoffs, but current Editorial Director David Perel acknowledges that they do pay for certain stories, and part of In Touch’s stigma stems from its willingness to pay for truly worthwhile tips and stories. LeGrice, who rose through the tabloid hierarchy in the ‘90s, sees it as a sort of quid pro quo: “If someone’s risking a lot by providing us with information, they need compensation.”

Tabloid journalism had thrived in the early 20th century in the U.S., but the Enquirer as we know it today didn’t coalesce until 1957, when owner Generoso Pope Jr. began filling the publication with celebrity and “personality” coverage — stories of everyday people with extraordinary lives, essentially the sort of people, like the Duggars, who make their way onto reality television today. The magazine was still as pulpy and sensational as it is today, but it wasn’t necessarily “distasteful”; indeed, it was the second-most popular magazine in America for much of the 1970s, eventually reaching a peak circulation of 5.9 million in 1978 while waging war with similarly successful competitors (Sun, Star, Globe).

But it wasn’t until the ‘90s that the tabloids developed their reputation for actually breaking stories: The Enquirer unearthed photos of O.J. Simpson wearing a pair of Bruno Magli shoes — whose footprint were visible at the crime scene, and which Simpson had repeatedly denied owning. In 1992, Star obtained the tapes outlining Gennifer Flowers' affair with then-presidential candidate Bill Clinton, a relationship he then denied on 60 Minutes, only to be confirmed, under oath, by Clinton himself in 1998. They found Jesse Jackson’s love child. They were the first to report that Rush Limbaugh was addicted to painkillers. They reported that Tiger Woods was having an affair months before he crashed his car in Jupiter Beach, Florida, and his sex addiction became public knowledge.

When Bauer Media first decided to launch a new magazine in the early 2000s, however, the plan wasn’t to make a tabloid — it was to make a hybrid. The multibillion-dollar publishing giant, based in Berlin, had been dominating the women’s interest market for decades with Women’s World, a cheap impulse buy (subtitle: “God Bless America!”) directed at working- and middle-class readers. In 2000, Bauer had watched its new British publication, Heat, take off after switching its focus to celebrities — and reality celebrities in particular. Bauer wanted duplicate Heat’s formula in the United States by mixing the content and cheerfulness of People with the cheap production of Women’s World and other Bauer publications.

According to LeGrice, whom Bauer brought in from Star to help design the prototype, “The idea was that the tabloids belonged to an older generation — Bauer wanted something that would appeal to the younger readers, as Heat did in the U.K.” Unlike the pulpy tabloids, the publication would be glossy, aesthetically and visually similar to the soft, bubbly pastels of People.

While most American magazines focused on cultivating subscriptions, even essentially giving magazines away so as to bring up circulation to a number appealing to advertisers, Bauer took a European approach: It was all about the newsstands sales. In Touch was originally priced at $1.99 — and periodically dipping to as low as 25 cents an issue — and the idea was to inspire an impulse buy in the checkout line. No matter that it had, in late New York Times media reporter David Carr’s words, “a slightly tacky look” — it was at least $1.30 cheaper than People.

Initially, the magazine hewed what LeGrice calls “the straight and narrow” — no exclamatory headlines, misleading photos, manipulative covers. Like the staff at Heat, In Touch's staffers cultivated relationships with reality stars who were still too down-market for People, and filled the magazine with banal, heartwarming stories like country music star Tanya Tucker’s Christmas Tree and “Touching the Heart: Sting, Julia, and Oprah are just a few of the stars who stand up for what they believe in.” But even while the content on the inside of the magazine stayed soft, the covers started to turn suggestive: “Prince William’s Secret Heartache,” “Is Julia Okay?,” “He’s Cheating!”

According to one former editor who asked to remain anonymous, this cover strategy, still very much in use today, “is no different than the links that fill my Facebook feed — they’re print version of clickbait.” That cover strategy is often traced to longtime celebrity magazine editor Bonnie Fuller, now editor-in-chief of Hollywood Life, who effectively resurrected Us Weekly over the course of 2002. A typical Fuller cover promised to answer a question the reader didn’t even know he or she had: “What Went Wrong,” “Why It’s Over,” or “Why They Split.” Both Us and In Touch also relied heavily on the booming paparazzi market sparked by the shift to digital photography: People didn’t read these magazines, they looked at them — and both supplied pictures of celebs in surplus.

The strategy, however derivative, worked beautifully for In Touch. The first issue hit newsstands in 2002; by 2004, circulation had reached 800,000 — and prompted Bauer to launch a sister magazine, Life & Style, intended to combine the ethos of Time Inc.’s InStyle and Conde Nast’s Lucky with Bauer’s low cost production. By 2005, circulation topped 1.1 million. It wasn’t that In Touch was siphoning readers from People so much as the celebrity industry at large was experiencing an unprecedented boom, as digital technologies (digital cameras, gossip blogs like Perez Hilton) ignited gossip storms around Britney and K-Fed, Brangelina, and TomKat. In the days before celebrity Twitter or TMZ, it was truly a golden age of gossip — and In Touch both accelerated and profited from the resultant celebrity fascination.

In Touch piqued that fascination by manufacturing elaborate, multipart, melodramatic narratives — the stuff of soap operas. Which made sense: The magazine’s editor-in-chief, Richard Spencer, came directly from Soap Opera Update. Several former employees remember Spencer laying out a four-act cover drama for what would happen between Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie at the beginning of each month — a pregnancy, for example, followed by a breakup scare, a reconciliation, and then marriage rumors.

The beats of the drama may have been fictionalized, but it was easy to find sources — including rival publicists, other celebrities, former friends, estranged family — to support the claims. Still, according to Jo Piazza, who served as executive news editor at In Touch from 2012 to 2014, “the majority of the stories were true.” “They were double-sourced,” she said. “It’s just that those sources were celebrities and publicists,” and then referred to as “a source close to the family” or “a friend.” It’s not that In Touch made things up; it’s that the publicists and family members and celebrities themselves did.

Leading up to the discovery of the Josh Duggar police report, In Touch used the same strategy for its coverage of the rest of the family. A Jan. 15 story questioning whether Jana Duggar was “pursued by family friend Zach Bates” cites “a family insider”; a piece from March 11 quotes a “source” for its claim that “Jana Duggar is allegedly ditching ‘19 Kids,’ Her Family, Patriarchy, Tater Tot Casseroles, Etc. Both stories serve the dual function of selling magazines and keeping the celebrity in question as an objection of weekly drama, fascination, and value — which is precisely why so many celebrities (and their publicists) are motivated to slip information to the tabloids.

Take the Kardashians, whom In Touch and Life & Style (and E!) transformed into the household names they are today. Several former employees confirmed that before Kim Kardashian’s sex tape with Ray J was leaked in 2007, Kim served as a source for In Touch stories, providing a steady stream of information on Paris Hilton. (A spokesperson for Kardashian states that the claim is "absolutely false.")

When Keeping Up With the Kardashians debuted in 2007, In Touch and Life & Style covers were instrumental in keeping the family in the gossip conversation, often through “exclusive” interviews. But those stories were “exclusive” in large part because at the time, no one else wanted to cover the Kardashians — and because their ever-expanding family tree provided a steady stream of easy-to-dramatize “news.”

Which is precisely what made the Duggars a perfect gossip mag fit: Even with their ‘80s hair and old-fashioned values, they provided just as many dating, marriage, and baby stories as the Kardashians.

Things started shifting in 2014, when amid plummeting circulation, Bauer replaced Editorial Director Daniel Wakeford with David Perel, a veteran of the tabloid world who had served as editor-in-chief for both Star and the National Enquirer, where he oversaw the team behind the John Edwards story. Like Spencer before him, Perel embraced the idea of gossip as narrative. “For David, each story is a chapter in a novel,” one recent staffer reported. “He decides on the narrative, then has reporters work sources to match that narrative.” (Perel responds that "in digital, we tend to introduce one news element at a time to tell some stories; in print we put all the news elements together into a cohesive unit.")

But as the Duggar story would soon prove, there’d also be the sort of investigative reporting that complicates the understanding of the tabloid’s place in journalism today. Perel quickly began disassembling Wakeford’s team and replacing it with his own from his days at the National Enquirer, including reporters Rick Egusquiza and Alexander Hitchen, both of whom helped break the Edwards story.

As Perel told the Washington Post, the In Touch staff had been evaluating the various rumors percolating around the Duggar family for some time. After the Barnfield photo went viral, Perel sent Egusquiza and another reporter to Springdale, where they did what Egusquiza describes as “good old-fashioned reporting on the ground and a lot of door-knocking.” Because Arkansas only allows residents to file Freedom of Information Act requests, In Touch also hired an Arkansas law firm to submit a request for anything on the Duggars.

On Tuesday, May 19, In Touch published a teaser post about Josh Duggar’s police report; on May 21, a follow-up post on the “Bombshell Duggar Police Report” linked to full, high-res images of the redacted police report, which indicated the extent of the abuse, the convoluted timeline between the time of abuse, Jim Bob Duggar’s reporting of that abuse, attempts to place Josh in church-run “treatment” programs for his behavior, and the tip to Oprah Winfrey’s talk show that culminated in a second investigation. That afternoon, Josh Duggar resigned from his post with the Family Research Council. On May 22, TLC put 19 Kids and Counting on indefinite hiatus; on June 8, People Magazine — which, just five weeks before, had featured a “Duggar Exclusive” of Jill’s “dramatic delivery” — put “The Duggars’ Dark Secrets” on its cover.

In the three weeks since first breaking the scoop, In Touch has chased the story relentlessly. And while In Touch acknowledges paying for stories, it seems that payoffs had no place in the Duggar scoop: just attention to the tip hotline and old-school legwork. Egusquiza (who refused to comment for this story) told The Advocate that “one tipster led to another, and then another,” but the smoking gun — and what differentiated the scoop from tipster-supported fodder that makes up so much of In Touch — was the documents.

That’s always been TMZ’s claim to legitimacy. After all, it doesn’t matter how garish your site is if you actually unearth irrefutable evidence: a grainy surveillance tape, a mugshot, a divorce filing, a police report. And then it forces even hard journalism outlets like the New York Times to credit “the tabloid In Touch Weekly” with the story.

Many of the tabloid journalists I spoke with forecast imminent changes in the industry: the Enquirer will hang on as long as there are aging, working-class Americans who have resisted going online; People will keep thriving in middle-market respectability; Us Weekly will continue its role as aspiring, resentful sibling. Several industry veterans predicted that OK and Life & Style will likely fold within the next two years, while Star and Closer will likely limp on. But with the tremendous power of Bauer and the investigative tradition of its current reporters, In Touch could potentially pivot into something more complex and interesting, something more like TMZ.

Until now, In Touch has occupied an identity-less space in the gossip world. Over the last 13 years, In Touch has never quite distinguished itself, or its coverage, from the celebrity news publications or the traditional tabloids. It succeeded in the 2000s not because it was offering a particular sort of celebrity product, but because it visually looked like the celeb magazines while offering the guilty, salacious pleasures of the tabloids — and for less than either. It was designed as an impulse purchase — an afterthought — and it remains one.

A single scoop won’t change that. But back in 2005, TMZ was an afterthought as well, at least until it broke the Mel Gibson story and spent the next 10 years establishing itself as both the go-to place for celebrity scandal and, arguably, the most influential publication of the decade.

In Touch could continue to pursue its hybrid non-brand, watching as circulation continues to decline. Or it could vie for TMZ’s throne by developing a legitimate web presence and doubling down on the old-fashioned tabloid investigative tactics that worked at the Enquirer and have proven so fruitful at TMZ.

Like TMZ, In Touch already dabbles in content of questionable taste — like a much-derided cover from January in which a picture of Caitlyn (then Bruce) Jenner’s face was photoshopped with lipstick and given the headline “My Life as a Woman.” It’s difficult to balance such regressive content with the potentially transgressive reporting, especially as that sort of eye-catching cover sells the magazines that makes the deeper, investigative reporting of the Duggars possible.

Still, tabloids are among the most deeply democratic, if often repugnant, forms of media. They adjust their covers according to what sells, and what sells generally caters to the most base and curious parts of ourselves. It’s painful to see that reflected so clearly in the bright yellow letters that hail us on the walk through the supermarket checkout. But celebrities embody the values and ideologies that matter to us, and the gossip magazines, tabloid or not, act out both our fantasies and fears as to what happens to those values in practice. If People gives voice to optimism — the triumph of the spirit, the goodness of mankind — then tabloids ventriloquize the inverse: True love sours, beauty fades, religious extremism perverts.

To reveal the truths behind the perfectly sculpted packages that celebrities provide isn’t just good for gossip. It boldly interrogates all that those celebrities seem to represent. And while Josh Duggar is no John Edwards, and the Duggar reporting won’t win a Pulitzer, the work that the story has done in interrogating the values of fundamentalism is very real and of unquestionable value. As Piazza told me, “Celebrities have so much power in our culture. They determine what we buy, what we think. They need to be called out, and places like In Touch do that when other publications won’t.”