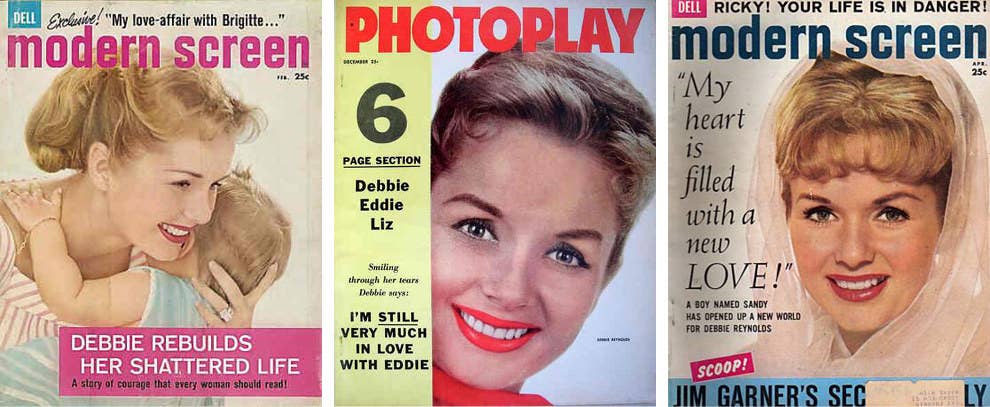

When people today think of classic Hollywood star Debbie Reynolds, who died Wednesday at the age of 84, they generally think of Singin’ in the Rain: Reynolds singing “Good Mornin’,” wearing an adorable rain jacket, shining those cherubic pink cheeks. Not me. I think of Reynolds, her eyes brimming with tears, on the cover of Photoplay, with the caption “I’M STILL VERY MUCH IN LOVE WITH EDDIE.” Or the cover of Modern Screen, a year later, depicting a smiling Reynolds holding her infant son, with the headline “Debbie Rebuilds Her Shattered Life: A Story of Courage That Every Woman Should Read!”

Reynolds was part of the biggest Hollywood scandal of the classic Hollywood era — an ongoing melodrama that would feature a grieving widow, furtive dates at nightclubs, four small children, a tracheotomy, and the launch of the paparazzi industry as we know it. But through it all, there was Debbie Reynolds, using the gossip magazines to model survival for an audience of millions.

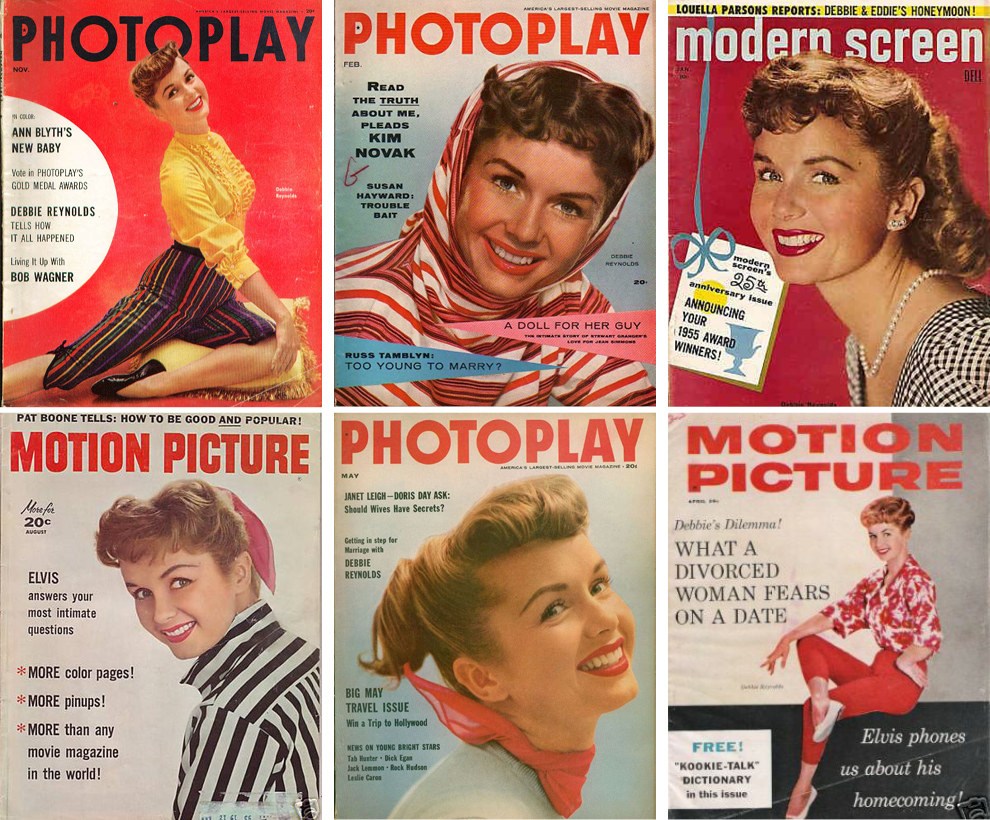

She was all of 19 when Singin’ in the Rain premiered in 1952, although she’d been in Hollywood, on contract, slogging through bit parts for years. But the role in Rain, for which she underwent extensive dance training in order to keep up with co-stars Gene Kelly and Donald O’Connor, made her an instant star — and a darling of fan magazines, which were hungry for an image like Reynolds’.

She was squeaky-clean, looking for love, and on contract to MGM, which meant endless access for all the profiles and photo shoots in the world — the sort of access that was increasingly unheard of as the stars began to leave the studios and go freelance. MGM was so keen to cultivate Reynolds’s “girl next door” image that its publicity department even circulated an anecdote detailing how Reynolds’ mother would embroider the star’s high school sweaters with “N.N.” to proclaim her “non-necker” policy.

For the next six years, Reynolds would appear all over the movie and fan mags, bolstered by follow-up roles in Tammy and the Bachelor, playing an adorable, naive 17-year-old, and Bundle of the Joy, starring opposite her new husband, Eddie Fisher, who’d spent the early ’50s establishing himself as the Justin Bieber–meets–Justin Timberlake singer of the era.

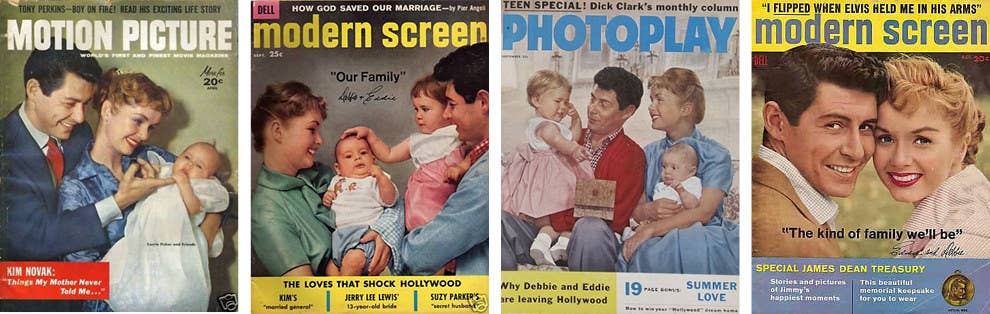

While Fisher was a good singer (and a mediocre actor), he excelled at starring as half of Hollywood’s cutest couple. When Fisher and Reynolds began dating, their interactions, at least in public, were chaste and traditional, in part because their dates were effectively “chaperoned” by reporters from both the fan and popular magazines, who documented everything from the couple’s “first public kiss” to their fairy-tale wedding at an “enchanted castle” in the Catskills. They were, at least according to the magazines, “The Cutest Couple in Hollywood.” Just look at all of these perfect poses!

The birth of their two children — Carrie, in 1956, and Todd, in 1958 — kept the couple on the cover of magazines even as Fisher’s popularity, in particular, began to wane and Reynolds appeared in fewer and fewer films. And while they were still incredibly popular, their popularity now stemmed from the narrative of their “real” lives — not necessarily their onscreen roles.

And when those real lives began to fall apart, an audience of millions watched with the same sort of obsessiveness as they would a soap opera storyline.

The building blocks of scandal first emerged in March 1958, when Elizabeth Taylor’s third husband, flamboyant producer Mike Todd, was killed in an airplane crash. The fan magazines profiled Taylor’s grief for the next six months, framing the "Widow Todd" in highly sympathetic terms while highlighting her emotional reliance on Todd’s protégé and best friend: Eddie Fisher.

In early September, rumors began to circulate that Fisher and Taylor had become romantically involved, spending late nights at New York nightclubs, where they’d even been photographed — a rarity at the time when the gossip press and studios had a silent agreement about not depicting stars when they went “off brand.”

Both Fisher and Taylor initially denied the rumors, and gossip columnist Hedda Hopper repeated Taylor’s denials in her column. But on Sept. 10, 1958, the scandal broke open. Taylor issued a statement declaring, “Eddie is not in love with Debbie and never has been. ... You can’t break up a happy marriage. Debbie and Eddie’s never has been.” Hopper, angry that Taylor had deceived her, penned a blistering critique of Taylor in her Sept. 11 column, including a misquote of Taylor that would be reprinted hundreds of times over the next decade: “Mike is dead, and I am alive.”

Reporters swarmed Reynolds at home, and captured the star in an iconic photograph, complete with diaper pins clipped to her blouse, which led on the front page of the Los Angeles Times. The photo’s caption became the template for Reynolds’ posture over the next year: “Still Smiling: Tears in her eyes, Debbie Reynolds, who told reporters she hopes she and Eddie can iron out their difficulties and ‘be happy,’ manages a smile as she makes a hurried trip home.”

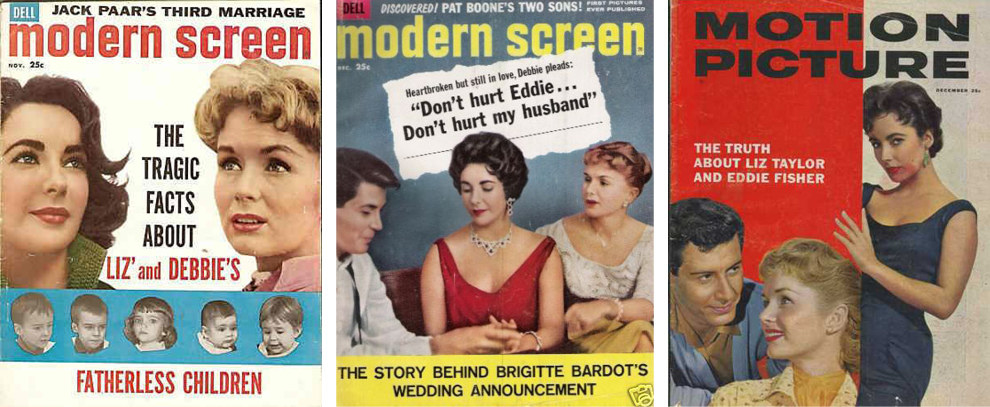

The press framed Reynolds as the victim while Taylor and Fisher played the role of self-centered home-wreckers.

Yet Fisher had already moved out, and the following day, the Los Angeles Times’ front page announced, “Debbie Will Seek Divorce from Eddie.” Soon after, Fisher made an official statement declaring that his marriage “was headed for break-up long before he even knew ... Taylor.” Reynolds’s carefully worded response declared, “it seems unbelievable ... to say that you can live happily with a man and not know that he doesn’t love you. That, as God is my witness, is the truth. ... I now realize when you are deeply in love how blind you can be. Obviously I was. I will endeavor to use all my strength to survive and understand for the benefit of my two children.”

With these statements as support, the press framed Reynolds as the victim while Taylor and Fisher played the role of self-centered home-wreckers. The two women were placed in opposition: Taylor, “the black widow,” against the sprightly, pigtailed Reynolds. Of course, these roles were rooted in the foundation of all three stars’ well-established Hollywood images. As a child, Taylor had been the star of numerous MGM productions, including National Velvet, a string of Lassie pictures, and Father of the Bride in 1950. Bride’s release coincided with Taylor’s own wedding to hotel heir Nicky Hilton, but the marriage quickly went sour, as a drunken Hilton purportedly refused to consummate the union.

Taylor’s divorce from Hilton in 1951 aligned with her starring role in A Place in the Sun, in which she played a wealthy socialite who so enthralls Montgomery Clift that he hatches a plan to kill his pregnant girlfriend so they can be together. Shortly after, in February 1952, she married again, this time to volatile British screen actor Michael Wilding, and gave birth to two children over the next five years. In January 1957 she divorced Wilding — and married Mike Todd a week later. Taylor’s consumption of men — coupled with a history of conspicuous consumption — trumped any potential image of her as a domestic, maternal figure.

Reynolds, by contrast, was as close as 1950s celebrity came to the perfect wife, mom, and daughter. In 1955, Fisher exclaimed, “She’s perfect for me, perfect for any man, but I’m the one she’s going to marry!” Reynolds penned a dating advice column for young girls, telling one that “if you don’t think kissing is proper, you shouldn’t do it.” She posed with Fisher and daughter Carrie, clothed in a baptismal gown, on the cover of Modern Screen; Fisher and Reyonolds sent telegrams to their moms as part of an advertising campaign for Western Union; they gave Screenland a tour of their Pacific Palisades home. Fisher’s best friend, Peggy King, told TV Radio Mirror that “if there are different kinds of loves — like different kinds of measles — then Debbie and Eddie have caught them all!”

Which is why Fisher’s actions seemed like such a betrayal: of his perfect marriage and of the legions of fans who’d invested in their relationship. And Reynolds, along with the fan magazines that had been so instrumental in propagating their “perfect” narrative, knew how to work that betrayal. Her studio contract dictated that she cooperate with the press, and the public airing of her personal trauma, in some way — so why not make herself the heroine and survivor in her own narrative?

That narrative was facilitated by Taylor and Fisher’s refusal to speak with the fan magazines. For Photoplay’s “Tragic Triangle,” for example, the article’s author relied on an interview with Fisher from before the breakup, employing Fisher’s statements to construct a divide between the fame-hungry singer and his domestic wife. While Debbie “prefers her own home, two infant babies, her garden and her constant reading of novels and scripts nightly in front of the fire,” Eddie “loves all this dearly but must also get out with people, travel, shake hands, listen, talk, and make friends.” Fisher’s philandering became an expression of rebellion against domesticity and, as an extension, Reynolds. “If Eddie and Debbie were having trouble,” the author wondered, “could this desire, or better still this craving to be liked — have anything to do with it?”

None of the magazines explicitly took any of the stars' "sides," yet early rhetoric clearly cultivated reader empathy with Reynolds.

An article titled “We’d Never Been Happier Than We Were Last Year” focused on an image of Reynolds, alone in a massive chair the estranged couple had bought in order to allow the entire family to sit together. “A few months ago, she had sat there with Eddie and both their babies,” yet “now, on this cold night, she was learning another way to sit in the chair — alone.” The author also envisioned a previous visit by Taylor and Todd to the Fisher home, imagining a conversation between Taylor and Reynolds: “So cheerful, Debbie — it’s such a happy room. It looks like you!” Taylor was easily framed as the literal interloper in the Reynolds-Fisher relationship, while the mention of her previous visits to their home amplifies her malice in “stealing” a man whose wife she had befriended.

None of the magazines explicitly took any of the stars’ “sides,” yet early rhetoric clearly cultivated reader empathy with Reynolds. Meanwhile, Photoplay framed Taylor as a woman living in her own private world, oblivious to the ramifications of her actions on others. “Did Liz Taylor know when the headlines were naming her as the immediate cause of trouble in the Eddie Fisher household?” Of course not, as Taylor “had spent most of her life in a sheltered, unreal world all her own — a soft, comfortable, pretty world, with her beautiful self at the center.” Within this world, “there was only a hazy dividing line between her own life and the make-believe life she lived on the screen, where everything always turned out happily.”

In this way, Reynolds became proof positive that traditional ideologies of femininity and sexuality, threatened by Taylor’s transgressions, remained intact. To perform this feat, Photoplay focused on the details of Reynolds’ life as a single mother and her unflappable, endlessly giving spirit. A January 1959 issue of the magazine depicts Reynolds kneeling beside her children, alongside the caption “Carrie Fisher’s question to Santa: ‘Is Daddy going to be with us all the time?'”

The deification of Reynolds persisted through the end of the decade, assisted by sympathetic headlines, including “I Never Knew Eddie Didn’t Love Me,” “Debbie Rebuilds Her Shattered Life,” and “I Wish Eddie and Liz Happiness.” Even after Reynolds’ MGM contract ended and she began to shun the press, speaking about their proclivity to misquote and misrepresent her, stories about her remained sympathetic.

All scandals demand reckoning — some satisfactory explanation of what happened, of providing redress, of stitching over the hole in the ideological fabric. In late 1958 and the decade that followed, fan magazine discourse attempted to reckon with the scandal by framing Taylor as the villainess, Reynolds as the traditional female ideal, and Fisher as the man blinded by Taylor’s light. But the ideological wound enacted by the scandal refused to heal: Magazines continued to print stories, and audiences continued to read them, well after all three parties had moved on.

The attraction was not to the actual people involved, but to the conflicts they embodied: More than any other public figure or fictional character of the time, the discourse around Liz, Eddie, and Debbie spoke to anxieties around the role of women and sex in American society — and about the vulnerability, and desperate need to preserve, traditional femininity.

Reynolds had been cast in a role in Singin’ in the Rain that clung to her for the rest of her life — a role that was ratified by her “real” domestic life throughout the ’50s and the actions of her husband at the end of the decade. As gossip columnist Louella Parsons put it in 1958, “I’m still digging myself out of the airmailed snow storm of letters directed to my desk about the Liz Taylor–Eddie Fisher–Debbie Reynolds holocaust. Some are bitter, threatening, and abusive. Some are disillusioned ('I’ll never again believe in a Hollywood marriage').” But Parsons also saw the roles that the members of the love triangle had come to occupy — and would continue to do so for the rest of their careers: Taylor was receiving the worst “blistering” of any star in her decades as Hollywood columnist, Eddie was the “mixed-up, infatuation-blinded, erring husband,” and Debbie — she was the heroine.

Reynolds spent the rest of her life trying to define herself not by what men — including second husband Harry Karl, who bilked her out of $3 million — had done to her, but what she, as a woman, had survived. As magazines attempted to make the story about feckless men and supposed feuds with other women, she recentered the story on herself: her triumphs, her survival. Years later, she and Taylor — who quickly divorced Fisher for Richard Burton — even appeared onscreen together, poking gentle fun at Fisher and the narrative that had been woven around them.

The temptation is to pit good Reynolds against evil Taylor, or to yoke her to her daughter, with whom she had a lovely, complicated relationship, and who died just a day before her. But I prefer to think of her the way she was on all those magazine covers: alone, but telling her own, triumphant story.

CORRECTION

Debbie Reynolds' second husband was Harry Karl. A previous version of this post misidentified him.

Want more of the best in cultural criticism, literary arts, and personal essays? Sign up for BuzzFeed Reader’s newsletter!

If you can't see the signup box above, just go here to sign up for BuzzFeed Reader's newsletter!