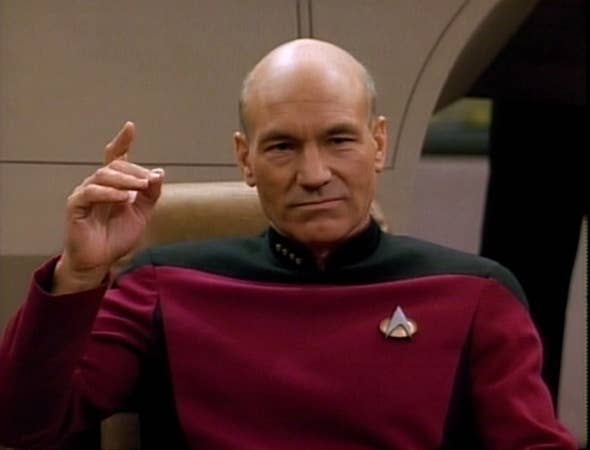

In a particularly poignant episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, Capt. Picard travels back in time to stop his younger self from getting stabbed in the heart in a bar fight. When he gets back to the present, though, he's no longer the captain of a starship — he's a law-abiding but lowly junior lieutenant. Getting in the fight, though it destroyed his heart, made him who he was.

It turns out there's good evidence that being the kind of person who gets in fights — or at least breaks the rules — can lead to success. But breaking rules doesn't usually go as well for women or people of color as it does for white boys, and changing that might be a necessary step toward equal opportunity.

A recent study [PDF] by researchers Ross Levine and Yona Rubinstein found that American entrepreneurs are twice as likely as salaried workers to report having taken something by force as teenagers, and 40% more likely to have been stopped by the police. The entrepreneurs also made significantly more money than salaried workers.

The study authors quote Apple cofounder Steve Wozniak: "I think that misbehavior is very strongly correlated with and responsible for creative thought."

That misbehaving and taking risks are associated with later striking out on your own — and making a lot of money doing it — may explain part of why boys underperform girls in school, but men out-earn women in corporate America. Girls tend to be better at following school rules than boys are, and research shows they're rewarded for that with better grades. But in the workplace, the impulse to break rules and be aggressive appears to be rewarded — even more so if you're impulsive enough to make your own workplace.

Some have argued that boys' risk-taking needs to be fostered more at school, and maybe it does, but it's also true that as they get older, men's aggression is rewarded much more than women's is. Women who are aggressive or competitive at work may be seen as less than feminine and be penalized for that — they likely face similar problems when trying to, say, convince venture capitalists to fund their new companies.

The kind of misbehavior Wozniak advocates may be hard for people of color too — after Trayvon Martin was killed, a number of black parents wrote that they taught their children to adhere closely to code of conduct in order to survive in a racist society. One mom's code included "disobedience is dangerous." For kids of color, getting stopped by the police is more likely to lead to jail — or worse — than to an entrepreneurial career.

All this is borne out by Levine and Rubinstein's study — they found that entrepreneurs were disproportionately white and male. They also come from higher-income and better-educated families than salaried workers — the people who take the most risks are also the ones with the biggest cushion to fall back on.

Encouraging women and people of color to take more risks and be more aggressive might help somewhat, but if those risk-taking behaviors aren't rewarded (or, in some cases, even safe), then the people who end up getting ahead will still be white men. Entrepreneurial activity will probably always entail a certain amount of risk — the only way to level the playing field would be to extend to young women and minorities the same indulgence that white boys get. It's hard to say what this would look like — encouraging more kids to steal or get in trouble with the cops isn't very good public policy. But there are ways in which (white) boys' misbehavior is treated as natural and expected, even if it results in worse grades. Those who worry about boys' education have advocated for letting boys be boys a bit more, but maybe we really need to let girls be boys.

Ultimately, Jean-Luc Picard found out that he had to break the rules severely in order to become a captain. But there's a gender gap even on Star Trek — the only woman on the bridge most seasons was the ship's counselor Deanna Troi. For her, getting in fights might not have made any difference.