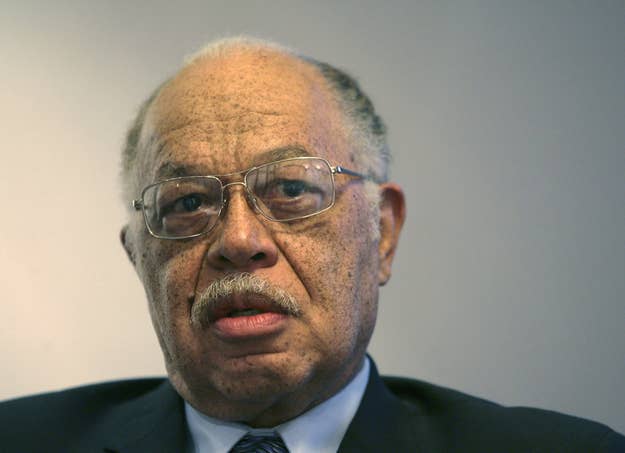

The allegations against former abortion doctor Kermit Gosnell are chilling: a clinic covered in animal urine, the spinal cords of viable fetuses cut with scissors, a pregnant woman dead. Predictably, the trial and coverage thereof have been controversial, with conservative outlets accusing mainstream and liberal ones of insufficiently covering it. But it's the controversial nature of abortion that makes abuses like the ones Gosnell's accused of possible in the first place.

Unlike other procedures performed by medical professionals, abortion is both heavily stigmatized and largely segregated from other forms of health care. And fear and stigma around abortion clinics (and abortion in general) can mean women don't even expect good care.

The majority of abortions take place not in hospitals or doctors' offices, but in standalone clinics devoted to the procedure. This is largely due to controversy around abortion: Bans on federal funding for the procedure make it hard for hospitals that accept such funding to also offer abortion care, and religious hospitals may choose not to offer the procedure as a matter of faith.

The allegations against Gosnell are in no way representative of all clinics. A study of women's abortion experiences found many patients were impressed with the support they received from staff there. But having to go to a separate abortion facility has real consequences for women. They may have to pass by protesters and go through security; one respondent in the same study said the clinic's secure door made her abortion "seem all the more like a secretive, shameful thing." And abortion clinics have become highly stigmatized — one abortion provider told me last year that one of her patients called a clinic "that terrible place," even though she felt she'd gotten good care there.

This stigma affects how women think they'll be treated at abortion clinics too. In a 2011 interview, Dr. Suzanne Poppema of Physicians for Reproductive Choice and Health told me, "because women think it's a bad thing, and it's shameful, etc., they go to a clinic that looks awful, that doesn't seem professional at all, and they're not scared away. ... Women don't expect to be treated with compassion, intelligence, professionalism, and good care when they're seeking abortion care."

If the allegations against Gosnell are true, then women surely deserved far better care than they got at his clinic (if "care" is even the right word for what allegedly happened to them there). But they may not have expected it, and because of the way abortion clinics are portrayed, they may have accepted terrible conditions as normal. And low expectations may have made patients less likely to alert the media or authorities to what was going on.

The grand jury report in the Gosnell case claims that abortion clinic inspections in Pennsylvania stopped in 1993 because a pro-abortion-rights governor, Tom Ridge, said they would put "a barrier up to women." Actually, Ridge stepped down hospital inspections in his state as well, privatizing many and reducing them from once a year to every three years. So whether his decision in the case of abortion clinics was an activist one is debatable. Still, the regulation of abortion clinics is a political issue in a way that can end up hurting patients.

Some laws affecting such clinics passed in the last few years aren't aimed at ensuring good patient care at all; they're attempts to shut clinics down. Mississippi Governor Phil Bryant said this explicitly of a law requiring physicians at his state's last clinic to have admitting privileges at local hospitals: "My goal, of course, is to shut it down." New clinic regulations in Virginia, stipulating things like the width of hallways, likely would not have prevented the kinds of abuses Gosnell's accused of either. The debate about clinic regulation today is typically a debate about shutting down clinics or keeping them open; it's rarely about ensuring existing clinics are safe. Integrating abortion with other medical care, and regulating it accordingly, would solve this problem.

Again, Gosnell's case is not a representative one and shouldn't be taken as an indictment of all abortion clinics. But separating abortion from other medical procedures and subjecting it to regulations that are political rather than medical creates an environment where substandard care is harder to spot — and where patients may not think they deserve anything better.