A woman is suing the city of San Francisco after its police department used her DNA samples from a sexual assault case back in 2016 to charge her with an unrelated property theft five years later.

Her case sparked outrage when then–district attorney Chesa Boudin denounced the practice in February as morally reprehensible, saying at that time that police may have violated the woman’s constitutional rights. He dropped the charges, and after the police department initially defended how it used alleged victims’ DNA, its crime lab changed its procedures.

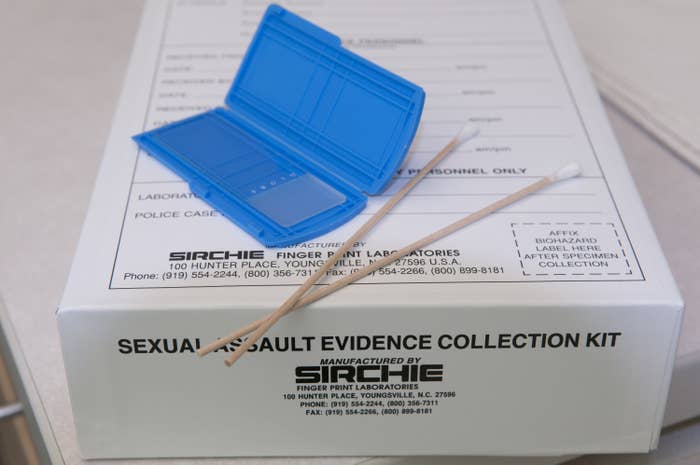

The lawsuit, filed in federal court on Monday, states that in 2016 the woman, identified only as Jane Doe, provided a DNA sample to the San Francisco Police Department after she reported being sexually assaulted. The lawsuit alleges that the San Francisco Police Department maintained the victim’s DNA in “the database for more than six years.”

“During this time, the crime lab routinely ran crime scene evidence through this database that included the Plaintiff’s DNA without ever attempting to get her consent or anyone else’s consent,” the lawsuit’s complaint says. “Her DNA was likely tested in thousands of criminal investigations, though police had absolutely no reason to believe that she was involved in any of the incidents.”

In December 2021, the police department used an alleged match between crime scene evidence and DNA that the woman had provided to arrest her on allegations of burglary, per the lawsuit.

“While all charges stemming from this incident against Plaintiff Doe were eventually dropped, the appalling, exploitative, and unconstitutional nature of the Defendants' practice cannot be ignored,” the complaint said.

In a press conference held on Monday, the woman's attorney Adanté Pointer said this wasn’t just the story of Jane Doe but “the story of countless other victims.”

“Jane Doe came to the police looking for help; she came to the police looking for them to do right by her,” Pointer said. “Instead, the police betrayed her and, by our count, thousands of other sexual assault victims.”

The lawsuit accuses San Francisco officials of instituting and maintaining “an unconstitutional DNA database of crime victims’ DNA without the victims’ consent or knowledge” and unlawfully arresting her. It’s seeking damages for “injuries, emotional distress, fear, terror, anxiety,” and “loss of sense of security, dignity, and pride as a United States citizen.”

In an interview with KTVU in March, the woman said that she did not know that the DNA could be used against her when she gave it to the police.

“I didn’t know that that could happen. I didn’t know that was even possible. I just feel violated again,” she said. “It was a slap in the face.”

When news of the incident broke earlier this year, legal experts and advocates for sexual assault survivors said the misuse of genetic information by police could keep people from reporting crimes.

“This attitude like somehow victims' DNA is fair game, it’s unacceptable,” Camille Cooper, vice president of public policy at the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network, told BuzzFeed News back in February. “There are women that are particularly at high risk for being assaulted because they may have criminal histories, right. And that doesn't make them fair game … and it doesn't make it OK for law enforcement departments to gang up on them and misuse their DNA.”

At the time, a dozen crime labs in California told BuzzFeed News they do not use sexual assault survivors’ DNA to investigate crimes. But San Francisco police did so on multiple occasions: In March, Chief Bill Scott said at a public meeting that he had “discovered 17 crime victim profiles, 11 of them from rape kits, that were matched as potential suspects” in unrelated investigations, according to NBC News.

Federal law already doesn’t allow police agencies to use victims’ DNA in the national database, but local databases like San Francisco’s are largely unregulated.

Lawmakers in California’s general assembly approved a bill last month that aims to protect sexual assault survivors’ DNA statewide. It has yet to be signed into law by the governor.

“Sexual assault is among the worst things that any person can experience, and we must do everything in our power to support and protect survivors who make the brave choice to come forward,” state Sen. Scott Wiener said in a statement when he introduced the bill.

“Sexual assault exams are traumatic enough as it is; we don’t need to create additional reasons for survivors to forgo them.”