On a map of Australia, Birdsville is situated toward the middle of the country, yet its remoteness is so absolute that it might as well be on another planet. Established in 1881, the town abuts the edge of the Simpson Desert, an enormous expanse that consists of more than 1,000 sand dunes. That a town was built here at all is testament to either human willpower or outright folly. It is not quite self-sufficient, as most goods are either trucked in via hundreds of miles of snaking gravel tracks dotted with roadkill kangaroos and carrion birds, or flown in via the twice-weekly mail service.

On windy days, the red dust from the desert blows across the town’s few dozen buildings, adding a fine film of rusty grit that bonds itself to every surface. On hot days — which is most of them — bush flies revel in the stark stillness, incessantly seeking out the moisture of sweaty human skin.

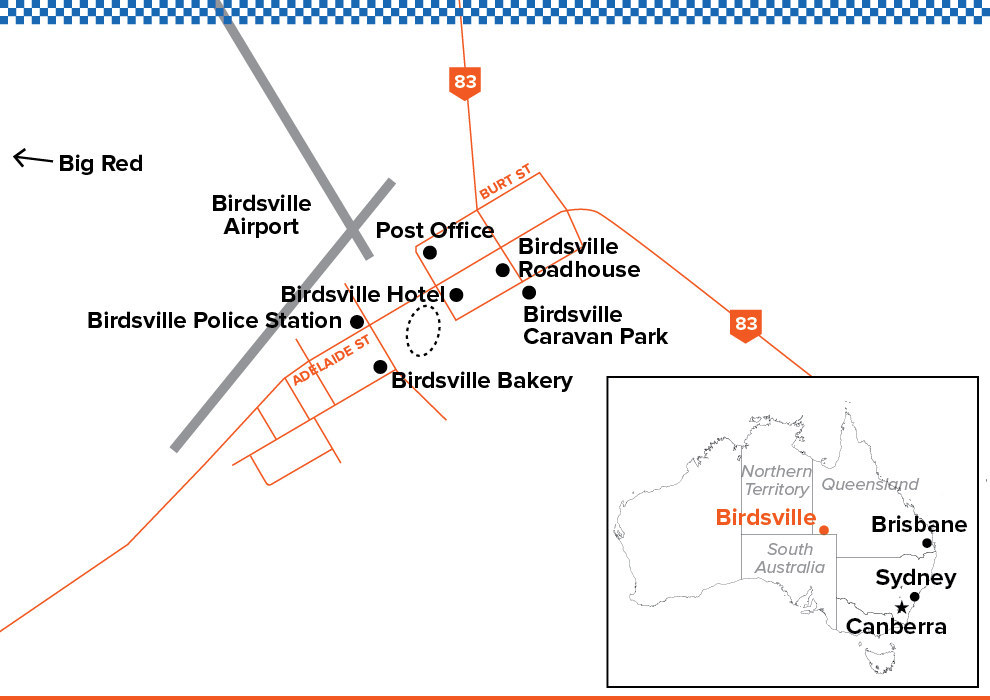

In Birdsville, if you want to buy a coffee, you have one option: the Birdsville Bakery. If you want to visit a restaurant, you have one option: the Birdsville Hotel. If you want to buy alcohol, you can do so from either place. If you fall ill, you’ll be treated at the Birdsville Clinic, and flown nearly a thousand miles to the state capital if you can’t be fixed there. If you want to buy basic groceries, you’ll have to settle for whatever Birdsville Roadhouse has in stock. If you want to see a film or live music, you’re in the wrong town. Birdsville State School has five students. The kindergarten has three. There are no teenagers. There is no crime. There is, however, a police station. It is manned by an officer who chooses not to carry a gun, because he has no need to.

The police station is situated at the edge of town, a short walk up the main street, toward the pub, the combined grocery store–cum–fuel station, a tiny airport, the school, and the clinic. When the airstrip’s runway-lights system is switched off at night, a stroll along this route reveals the breathtaking volume and variety of stars overhead, which flicker brightly, knowingly, free of all light pollution. Shooting stars are seen more often than cars on the main street, which might be used by 30 vehicles on a busy day.

For most residents of Queensland, Australia’s second-largest state by area, Birdsville will only ever be a geographic curiosity seen at the edge of the map on the nightly weather report. Locals say the population is 80 people, half of whom are Indigenous Australians, but the sign posted outside of town notes that the population is "115, +/- 7,000." After driving over a thousand miles to be here, seeing that sign somehow quickens the pulse. Once a year, during the first weekend of September, this sleepy desert town sparks to life, relatively speaking.

The day before the biggest annual social event on his calendar, Senior Constable and Officer-in-Charge Neale McShane leans against the front desk of the Birdsville Police Station, holding court as a stream of incoming tourists drop by. First, two fresh-faced, off-duty police officers from Emerald, a 16-hour drive northeast, introduce themselves and shake his hand. “Wanna throw a swag down?” asks McShane. “Plenty of spots, mate,” he says, heading outside to show them a nearby clearing in the red soil where they can set up camp.

Then, in walks an arguing middle-aged couple, who have somehow made it here in their two-wheel-drive Ford Focus, a small car whose clearance is barely high enough to avoid the baseball-sized rocks that litter the wide gravel roads leading into town. They ask McShane for his wisdom on making an exit back east. “Go early,” he advises. “If you leave Sunday, you’ll be suckin’ dust all the time, ay.”

Next, a couple of rough-looking blokes with leathery, tattooed skin and abundant facial hair from Boulia, an over six-hour drive north, ask about camping away from the racetrack crowds. They look as though they’ve had a few interactions with police over the years, not all of them positive. “Stay outside the town limits, and you can camp anywhere,” McShane replies with a grin. “Just pull up a bit of dirt.”

Tall, clean-shaven, silver-haired, and in possession of eyes as blue as his spotless police uniform, the officer-in-charge is a picture of friendly authority as he interacts with these strangers. The tourists’ Thursday-morning queries are the calm before the storm of the next few days, when an annual horse-racing event first held in 1882 brings with it an influx of people, alcohol, money, and the potential for violence.

Usually, however, McShane’s weekday mornings are much, much quieter than this. A sign on the fridge reads "Birdsville Social Club — All drinks, all chocolates, $1.00." The club has two members — him and his wife, Sandra, who is a blonde 60-year-old with brown eyes. She works 16 hours a week at the station as an administrative assistant, since the building also doubles as a Queensland Government Agency, processing vehicle and gun license paperwork, as well as paying out $21 for each dingo scalp brought in by local shooters, as part of efforts to control the native dog.

The Birdsville posting is a one-officer station — a relative rarity in a profession built on partnerships — and McShane has lived at the neighboring house for almost a decade, through dust storms and floods, through joy and tedium, through good health and bad. On Nov. 21, the day of his 60th birthday, his 40-year career will end, per conditions of the Queensland Police Service, which mandate compulsory retirement at this age. He will retire as the longest-serving officer at Australia’s most isolated outpost, having spent 10 years policing a jurisdiction that covers about 93,000 square miles — roughly equivalent to the entirety of the United Kingdom being nuked, then being in charge of a few dozen survivors.

A white Toyota four-wheel drive parked beside the MacDonald Street station is emblazoned with distinctive red-and-blue roof lights and the bold insignia of the state’s police service. As the midday sun blazes overhead, McShane quietly patrols the crowded streets, surveying the tourists through wraparound sunglasses and serving as a silent reminder to any would-be troublemakers that the laws of the land extend even to the edge of the desert. “This is a friendly event; everyone is here to have a good time, by and large,” he notes.

While cruising with the windows up, to keep out the persistent flies, McShane points out the town supermarket, which has “a pretty nice array of goods; they can get anything you want, like tomato sauce, but they’ve only got one brand. Or biscuits, but only one brand,” he laughs. He gestures at the local tennis court where he won $11 at the first annual Birdsville Open a few years ago, “on the same day that Rafael Nadal won $10 million at the French Open.” A sign at the edge of town shows that the nearest capital city, Adelaide, is 740 miles south, while the Queensland capital of Brisbane is only a leisurely 995-mile drive east. He gives a friendly wave to all who make eye contact, and most people happily return the gesture.

After stopping at a gas station, an Indigenous Australian artist approaches the four-wheel drive and greets McShane by his first name. “Hey, they tell me you’re retiring soon!” the man says. “I heard it on the radio! Are you gonna come back home to Charleville to live?” The senior constable nods, smiling. “Too right!” he replies, pleased at the thought of returning with Sandra to the central Queensland town — population 3,500 — where he served as sergeant between 2001 and 2006.

As the vehicle loops back toward the station, past the pub teeming with buzzed punters whose empty beer cans litter the sidewalk, McShane can’t help but marvel at the change. Usually on a Thursday, there’d be no one here other than a tumbleweed blowing up the main street. Peering out the window, he smiles and says, “Gee, the town’ll be jumping tonight, ay!”

During the cooler months, between April and October, the town sees approximately 45,000 visitors passing through. Tourism largely comprises “gray nomads” — retirees in campervans and caravans — for whom exploring Australia by road is a significant life achievement waiting to be checked off the list. But for much of the national population, which is concentrated near the urban centers situated on the East Coast, the country’s famed Outback hardly ever crosses the consciousness. Most Australians are far more familiar with the sand of surf beaches than the red dust of the desert.

Agriculture is what keeps most of the town’s residents here. There are only a handful of cattle farming properties in the area, which has developed a strong reputation for supplying high-quality organic beef throughout the country and internationally. During the hot summer months between November and March, when temperatures regularly exceed 100 degrees, many residents seek respite from the heat by relocating elsewhere until the weather cools.

Once a year, however, the town explodes in a frenzy of noise and activity with the annual Birdsville Races, held the first weekend of September. To provide for the 7,000 or so visitors, three refrigerated semi-trailers filled with ice are trucked in, as are three road trains supplying gasoline and diesel fuel. Some 80,000 cans of beer are sold. Set up opposite the central Birdsville Hotel is the country’s last remaining tent boxing troupe — outlawed in Victoria and New South Wales, Australia’s two most populous states — which attracts hundreds of spectators for two shows a night between Thursday and Sunday. Plucky — and sometimes intoxicated — challengers of all genders are encouraged to don gloves and fight against experienced boxers for a chance at glory.

Throughout the weekend, the bakery does a roaring trade in its famous curried camel pies and kangaroo pies. Above the door, a powerful fan features a handwritten note and an arrow pointing at the floor: “Fly removal zone.” Another sign on the door reads: “Please have a good go at leaving the flies outside.” Inside, an Australian flag is attached to the ceiling, the walls are lined with Outback cartoons, paintings, and postcards, and the center of the room is dominated by a scale replica of a windmill. Plastic cutlery and towering bottles of sauce are provided free of charge. The team began preparing stock in March, expecting to sell more than 14,000 pies, sausage rolls, and pasties in the couple of days surrounding the races. Owners Dusty and Jacko Miller established the store in 2004 with no previous baking or retail experience. It might be the country’s only bakery licensed to sell alcohol, a fact that its staff are keen to emphasize. Every food purchase comes with an offer for “a cold beer to wash it down with.” Refusals are met with a queer look and a question: “What’s wrong with ya?”

Many of those who attend the races opt to set up camp in the dusty scrub that lines the road heading out to the racetrack, where state-of-the-art RVs are situated beside those who choose to rough it in simple swags laid beneath trees, in the hope of sheltering from the highly unlikely event of early spring rain. It has happened before, though, most recently in 2010, when torrential rainfall caused widespread flooding in the region’s surrounding river systems, cutting off the roads and trapping thousands of racegoers in town for at least two days. The local supermarket ran out of supplies, but the hotel was well-stocked in beer, and the town’s last pack of cigarettes was auctioned off for $200, McShane recalls, with proceeds going to the Royal Flying Doctor Service, an aeromedical health service for those who live in remote parts of the country. This was the third time in Birdsville's history that the horse races were canceled, but for McShane, keeping that stranded crowd fed, watered, and happy for the entirety of that weekend in 2010 is his proudest career achievement. “Better to have them all stuck here,” he says, “rather than stuck on roads throughout western Queensland and South Australia.”

It takes a certain type of person to want to take up the role of Australia’s most isolated police officer. To want to stay here for 10 years is another matter entirely. Birdsville has traditionally been a tough posting to fill, and its constabulary have not always coped with the harsh environment. In 1882, a year after the Queensland government reserved 4 square miles around a central store and gave the town a name, a police officer killed himself here when a woman turned down his marriage proposal, according to Evan McHugh’s 2009 book. In the station’s journal that day, Sgt. Arthur McDonald wrote, “Sub-Inspector Sharpe shot himself on the police station verandah [sic] this afternoon. Another hot day in Birdsville.”

Born in Adelaide, McShane, the second eldest of five boys — “Mum said she wanted a girl, but she gave up after five" — spent his first five years in London, where his father worked in dairy exports. The McShane family then returned to Byron Bay, on Australia’s East Coast, and at 19, after realizing that he didn’t want to work in an office, McShane joined Victoria Police in 1975.

When the Birdsville posting was last up for grabs in 2006, the Queensland Police Service advertised it three times before receiving an inquiry. Stationed in Charleville as a sergeant at the time, McShane had noticed the job ad. “I’d never been in charge of a police station, and I intended to stay here until I retired,” he says, sipping a mug of instant coffee in his office, where a large can of fly spray sits beside the telephone, within easy reach.

After being offered the job, McShane accepted a demotion to senior constable, but he enjoys a string of perks that include a remote posting pay bump (around $3,500 USD annually), additional holiday pay to help with the cost of traveling east ($1,100 biannually), and a grocery allowance ($250 fortnightly). As his career draws to a close, his annual salary is $72,000.

This might sound like a lot for the task of policing a sleepy desert town, but factoring in his responsibility to be on call for all manner of community concerns — vehicle accidents, desert rescues, euthanizing ill animals — at any time of the day or night, it’s hardly a walk in the park. His jurisdiction also takes in three state borders of Queensland, South Australia, and the Northern Territory. “I’m a police officer in three states, so every fortnight I pick up three paychecks,” he tells a visiting colleague. He waits a beat, then cracks up: “Nah, only kidding, Kate. Tell you what, if I did, that post wouldn’t be advertised three times!”

A description of the station on the Queensland Police Service website notes that “Birdsville is a very law abiding community that lives in harmony and crime is virtually nil.” True enough, the back of McShane’s four-wheel drive contains rescue gear and a fridge, rather than the standard-issue “prisoner pod.” His last arrest was in January 2014, when a driver in his mid-twenties filled up his tank in Windorah, 235 miles east, and left without paying. When McShane picked him up in Birdsville, the thief was found to have a police warrant out in his name, as well as being disqualified from driving, so he spent a couple of days in custody in Mount Isa, a 10-hour drive north.

His last arrest at the races was four years ago, when a middle-aged man from South Australia got so drunk at the Birdsville Hotel that he caused a scene and pissed his pants. “I went up there and said, ‘Tell you what, mate, we’ll take you home, have a camp, and come back tonight.’ He said, ‘Get fucked,'” recalls McShane. “He spent 18 hours in the cell here because he wouldn’t give us his name.” Once he sobered up, the man was bailed out on the condition that he wouldn’t attend licensed premises, including the pub and racetrack, before being fined $350 in court on Sunday.

Working in such an isolated environment presents a raft of challenges for a role that demands impartiality at all times. “You don’t want the community to be scared of you; you want them to talk to you, but you’ve still got to enforce the laws,” says McShane. “So you can’t go up the pub and drink with them ‘til midnight. You’ve got to have that barrier.” It’s important for him to stay out of town politics — “You’re like Switzerland; you’re neutral" — and to not cart gossip. Uniquely among Australian police, since being stationed at Birdsville, McShane has chosen not to carry a firearm, although technically he’s meant to. The only time he opens the weapon safe inside the police station is when locals come to him to put down their animals, since there is no town vet. McShane has drawn his gun while on duty elsewhere, but is thankful that he’s never had to pull the trigger in such a situation. “I’d hate to ever shoot someone,” he says.

Early in his career, McShane heard a commissioner describe policing as “a front-row seat to the best show in town,” a phrase that still rings true in his mind. “It’s a good job,” he says. “You get a really good sense of camaraderie with people.”

In the week surrounding the two-day race, the sandy backyard of the Birdsville Police Station swells with some two dozen friends and former colleagues of the McShanes, who arrive with camper vans and tents. Retired army majors, pharmacists, painters, and former Australian ambassadors to Hong Kong are among the guests. As the sun inches toward the horizon, McShane is often found at the center of the yarns that are told around the campfire each evening, either as the storyteller or as the narrative focus.

Can of Coke Zero in hand — his doctor has strictly confined his daily alcohol intake to one glass of red wine — McShane tells a curious newcomer that he suffered a stroke while on duty in May, and that he’s been on "light duties" at the station while he continues his recovery. He waits a beat, then grins and says, “But I’ve been on light duties for 10 years, so it’s not all that different!”

All in attendance are aware that 2015 is the last year that the McShanes are working the races in an official capacity, and this gathering has assumed a heightened sense of importance since his stroke. There are few secrets in small towns, a fact magnified when illness happens to befall Birdsville’s only police officer: This news has been reported in the national media, and many of those camping in the backyard are here primarily to support their mate and his family in their time of need.

During the week, the two toilets inside the recently painted police station are given a workout, and its shower — cold water only — provides the backyard visitors with bracing relief from the dusty, warm days. Inside, extra officers sleep at the barracks, while others are posted in the garage, beside the deep freezer and washing machine. One unlucky visitor draws the short straw and sleeps on a stretcher near the lockup cells beneath a bright fluorescent light that stays on all night.

Ants snake across the sand, thickening during daylight hours as the desert insects’ food sources increase dramatically with the out-of-towners and their imported goods. McShane keeps an eye on equipment installed by federal government scientific agencies monitoring dust content, ozone levels, and tectonic plate movements, as well as a rack of fencing and roofing materials used to measure their durability beneath the harsh desert sun.

On Friday morning, a few hours ahead of the racetrack opening its gates, the interstate cop contingent gathers at the red-roofed courthouse building. Situated at the end of MacDonald Street, two doors down from the station, the courthouse no longer fulfills its role as a place of judgment; this weekend it’s home to some of the makeshift police force, most of whom have driven south from Mount Isa to support McShane.

As the cops are corralled into position to pose for some photographs, Sandra is roped into the shoot, too, her navy blue Queensland Government polo shirt all but indistinguishable from those of her husband’s colleagues. Visiting Superintendent Russell Miller addresses the group as they’re dismissed. “Have a good day, everybody,” he says. “If you’ve got any hot tips for the races, let us know!”

Miller is certain that McShane is Birdsville’s longest-serving officer. “I’d be very surprised if anybody ever surpasses him,” he says. He doesn’t think it’ll be too difficult to fill the role this time around; it's a far more attractive career choice than in the pre-internet age, when the town’s geographic isolation was felt much more keenly.

Neighboring the police station and courthouse is the Birdsville Airport, a recently upgraded building that’s still little more than an air-conditioned tin shed. Abutting the terminal is an airstrip that sees plenty of traffic this weekend, but little else during the other 51 weeks of the year, besides the occasional Royal Flying Doctor Service visit, twice-weekly drop-offs from the mail service, and a regional airline that services passengers to and from capital cities. Parked inside the chain-link fences that surround the area are over 100 small aircraft, beneath the wings of which many of the pilots and their passengers have set up tents. Since the airstrip neighbors the Birdsville Hotel, too, it’s also probably the only place in Australia where you can land a plane and taxi the aircraft almost directly to a cold beer tap.

The Birdsville Races are much like a regular horse race, only much dustier, a fact of life that has become a marketing slogan for the event: “The dust never settles.” With just 13 horse races scheduled across two days, there’s plenty of time for socializing, drinking, placing bets, and witnessing the Fashions on the Field competition, which awards prizes for best dressed couple, family, gentleman, and "classic lady" over 18 ("Exposed shoulders and cleavage are not true Ladies Racewear,” notes the judging criteria). The standard of dress varies widely, from smart suits and sharp gowns to the year-round Queensland staples of shorts, tank tops, and flip-flops. Broad-brimmed hats abound.

The officer-in-charge’s youngest son, Robbie, has lobbed into town overnight, with his girlfriend Bec in tow. The pair decide to avoid the race crowds by making tracks toward an iconic landmark named Big Red, the largest sand dune in the Simpson Desert. It’s a short drive from Birdsville, in true four-wheel-drive territory. Robbie is a tall, affable 24-year-old with similar facial features and speech patterns to his father. He grew up in Melbourne, then Cairns, attended high school in Charleville, and now works as an electrician in a coal mine near the central Queensland town of Tieri, a 17-hour drive northwest of his old man. Before he visits, Sandra gives him a grocery list of foods to bring to Birdsville, ones the general store normally doesn’t carry: dips, cheeses, special cuts of meat. “I got him to bring out some diced lamb so we can have some nice Indian meals,” Sandra says. “Robbie hasn’t given me the bill yet, but it’s normally around $100 [around $70 USD].” As country music plays softly on the stereo, he expertly drives his white Toyota at 60 miles an hour along the gravel road, occasionally sipping from a cold can of XXXX Gold.

While he gives the strong impression of being a fearless, openhearted young man, Robbie admits that the sight of his seemingly indestructible father laid out in a hospital bed shook him. “It was a big shock, ay,” he says. “But it was good seeing him improve. The physio had three stairs for him to walk up and down 10 times per day. She’d say, ‘Whoa, you’ve done so well!’ But in the meantime, he’d be going up and down four flights of stairs, 10 times a day, without her knowing. He’s still got a bit to go, but it could have been a lot worse.”

In the afternoon light, the vistas from the crest of Big Red offer phenomenal views of desert plains as far as the eye can see. After watching some other drivers attempt to climb the dune from its steeper western approach, however, Robbie’s testosterone gets the better of him. Itching to repeat what he has just seen, he leaves Bec at the top and drives the long way around, before gunning his vehicle at maximum speed to try and make it up. Returning to his girlfriend afterward, he says, “The first time I went up, my beer was half full — bang, it went everywhere,” Robbie grins. “So I went back down, finished the beer, and tried again.” Three times he nears the top before running out of momentum, requiring him to sheepishly reverse back down the dune, but his fourth attempt is successful, drawing cheers from the dozen or so witnesses, while his wheels spray fine red dust at the summit.

Birdsville State School has become a makeshift magistrates court for the weekend. A one-teacher campus whose current enrollment is just five children, the school’s emblem is a pelican and its motto is “Strive to succeed.” Affixed to the surrounding walls of the central teaching area are several motivational quotes. “You can never be overdressed or overeducated.” Eleanor Roosevelt: “The future belongs to those who believe in the beauty of their dreams.”

On Saturday morning, McShane and Acting Senior Constable Kate Plant — who helped to manage the Birdsville posting while he recovered from his stroke — are waiting amiably with paperwork and a speakerphone set out on the desk before them. Sandra arrives just before 8 a.m., removing her hat and taking a seat adjacent to her husband. Looking around the room, her eyes settle on a laminated sheet of white paper, which states that teachers who love teaching teach children to love learning. “That’s so true,” she says quietly.

McShane met Sandra, an airline attendant for Trans Australia Airlines, while on holiday at South Molle Island, amid Queensland’s vast Great Barrier Reef. The couple married in 1978, both age 23. Together, they raised three children — two boys, one girl — first in Victoria, and then in Queensland, when McShane transferred in 1995.

This is the first time that Sandra has attended magistrates court in Birdsville; she figured that she’d better not miss this last opportunity. Across from the police officers sits a legal representative clad in a black suit, and the first of five defendants, a 21-year-old Indigenous man who is smartly dressed in a red-and-white-striped shirt worn beneath a sports jacket. He nervously handles a white trucker cap while seated beside his legal counsel, perched between a photocopier and rows of filing cabinets filled with teaching resources.

After glancing at the clock, Sandra leans over and says, “Neale, what time’s it starting?”

“Eight o'clock,” he replies. The clock now reads 8:15. “The wheels of justice turn slowly."

Suddenly, the phone rings. “Senior Constable Neale McShane, Birdsville Police,” he says, and at the other end is a sleepy-sounding magistrate based in Townsville, a coastal city situated 832 miles northeast. “Good morning, sir,” he says.

“Doing this over the telephone — has it happened before in Birdsville?” the magistrate asks.

“Yes it has, your honor. We’ve had phone hookup for the last few years.”

“All right. And this is the way you conduct court in Birdsville, basically, because of your isolation? How often do you convene court?”

“We convene court twice a year, on the Saturday and Sunday of the Birdsville Races, your honor,” McShane replies.

“I see,” says the magistrate, satisfying his curiosity before moving onto the court’s first matter for the day.

The Birdsville Hotel.

Per a reading of the facts, the first defendant — a local man who works as a ranch hand — is charged with bodily harm, as a result of punching a 39-year-old duty manager of the Birdsville Hotel in the face while intoxicated at 1:15 a.m. on April 18, after he observed the manager dancing with his ex-girlfriend. He pleads guilty, and justice arrives swiftly. “You’ve taken your anger out on the wrong person,” the magistrate observes. “One can understand that jealousy arises, and given that you’d taken some alcohol on board, your judgment was probably impaired. You are fined $750 [around $530 USD], and I do not record a conviction against you, but I order you to pay compensation to the victim of $750 also. That concludes this matter.”

The final four matters each pertains to tourists’ drunk-driving charges, and in the sober light of morning, the regrets of each defendant are plain to see. One by one, the men each plead guilty, including a 31-year-old truck driver from Victoria dressed in a blue flannel shirt and shorts who offers to pay a greater fine in an attempt to reduce the duration of his license suspension. “I’m prepared to give the minimum disqualification period, which is three months,” says the judge, who bumps up the fine to $650 and records a conviction. There is a heavy sigh as the truck driver leaves the room, crestfallen.

In McShane’s experience, 95% of people are good: They want to respect laws, and they want to help police; in that spirit, he wants to offer opportunities for lawbreakers to right their wrongs. “You don’t just commit an offense and go straight to jail, unless it’s a very serious one,” he says, citing the assault at the hotel as an example. “That guy’s got no previous history, but alcohol, jealousy, and violence are a bad mix. Him getting convicted is good for the community, because gossip goes around like wildfire. There’s gotta be consequences for your actions.”

If police are a mirror of society, as McShane believes, then sometimes the picture that emerges in the reflection isn’t very pretty. After their first child, Andrew, was born, McShane came home with a rule one day: Don’t talk about bad stuff at the dinner table. There are some parts of life that elude protection, however, as McShane learned this past May.

“He doesn’t whinge about anything," says Sandra. "He’ll say, ‘Eat some cement.'” In other words, harden up, a motto well-suited to remote Australia. After playing an afternoon game of touch football with some friends, the next day was a busy one for the officer-in-charge — he attended to a traffic accident, and then a drunk-driving incident; then a motorcycle rider came off his bike about 50 miles west of Birdsville.

Around 6 p.m., he and Sandra hopped in the Toyota — her first and last time attending a rescue — and arrived three hours later. The man had broken his foot and leg. The town’s full-time nurse, Andrew Cameron, met the McShanes on-site, and put a drip line into the patient. The rider was only an average-size bloke, but when it came time for the two men to lift him into a vehicle, the effort put McShane under surprising physical stress.

When McShane woke the next morning, he couldn’t move his right hand. He had trouble buttering his toast, and when he attempted to deliver a cup of tea to Sandra in bed, he spilled half of it on the floor. “His eyes looked odd and vacant,” she recalls. Trained in identifying strokes as part of her career as a flight attendant, Sandra conducted a series of tests, which he passed without discomfort. Still, she rang Cameron, then drove McShane to the clinic, where his condition worsened and the Flying Doctor was called in to pick him up less than 12 hours after he had seen off the motorcyclist.

During McShane's recovery at the Princess Alexandra Hospital in Brisbane, the Queensland Police Service put Sandra up in an inner-city apartment, where she stayed between daily visits. Senior police officers stopped by to support their most isolated officer. McShane was in the hospital until July 7, walking a couple of miles a day on a treadmill, gradually retraining his brain to build new connections to work around what was lost. He readily admits that he was out of shape prior to the stroke — partially a result of Birdsville’s lack of access to fresh vegetables, as well as severe summer temperatures that discourage regular exercise — but the health scare has seen him shed 22 pounds. Though not yet back to full capacity, he’s getting there. And, even with retirement looming, he hardly considers himself finished at 59. “There’s more to do.”

On Sunday night, with the sounds of the Birdsville Hotel’s live music performances still booming across the desert landscape, Sandra leads a group of around a dozen friends and off-duty Mount Isa cops to a dark, rocky spot behind the old courthouse, where the only light pollution comes from the occasional high beams of cars entering the town from the west.

Beneath a darkened sky dotted with pinpoints of white and yellow lights, she sets up her hefty 11-inch Celestron telescope, made in the United States and bought in Sydney, having charged its battery earlier in the day. Sandra’s interest in astronomy grew out of a job advertisement for a star guide while the family lived in Charleville, where she worked at the renowned Cosmos Centre, becoming a senior guide and trainer before moving to Birdsville and hosting her own private star shows, for $10 per adult.

Though a little rusty in her delivery at first — she has not led a stargazing group since the beginning of the year, before her husband’s stroke — she soon slips into a mode that is equal parts educational and entertaining. “What you’re doing now is no different to what the ancients have done for thousands of years,” she begins. “They’ve sat down under the night sky, looked at objects, and thought, That looks like a shape.” Her passion for this work is abundantly evident, as she shows the group the dust rings of Saturn, the Jewel Box cluster, and Omega Centauri. At her command, the telescope dutifully repositions itself with a pleasing, mechanical whir. Using a high-powered green laser pointer, she shows the group of desert visitors how to find true south using the Southern Cross. “Then you’ll never get lost,” she says, “so you’ll never have to call Neale.”

The last object Sandra shows the group is Albireo, the fifth-brightest star in the constellation Cygnus and her personal favorite. Albireo appears as a single star to the naked eye, but the Celestron resolves the object in its true form of a double star. She found it while working at the Cosmos Centre, and she loves it for the simple reason that it’s beautiful.

One by one, the stargazers peer through the scope’s impossibly powerful lens. Albireo reveals itself: One of its stars is golden, the other as blue as a police uniform. Despite the distance, the objects seem close together, and appear much sharper than the surrounding backdrop of unending darkness. The pair burns brightly, way out there, a glorious union in the middle of nowhere.