To mark six months since a pandemic was officially declared, BuzzFeed News is publishing The Lost Year series: six stories of six people from six different age groups across the US. Each day this week, we are profiling a new person to see what toll the coronavirus has taken on their lives. In this fifth installment, we meet a nurse in her sixties in Florida.

After three decades as a labor and delivery nurse, Marissa Lee still gets a kick out of seeing babies being born. “It’s such an adrenaline high to watch that little person take that breath,” said the 63-year-old.

But it’s hard for her to find joy amid the coronavirus pandemic. There have been shortages of personal protective equipment and staffers, she said, as well as nurses sick with COVID-19 at her workplace of 16 years, the Osceola Regional Medical Center in Kissimmee, Florida, just south of Orlando.

Giving birth is physically draining — if you think going for a jog is hard with a mask on, try going into labor with one. Nurses are normally very hands-on with pregnant women; this makes social distancing nearly impossible and could make for a less supported labor.

Occasionally, Marissa witnesses the horror of a mother losing her child, but she is expected to keep her distance. On one of her recent shifts, a fetus died in utero. The mother still had to go through the birthing process, with Marissa by her side, knowing it would be a stillbirth. As someone who spent years trying to get pregnant before having her two now-adult daughters, Marissa felt deep empathy for her. But the woman didn’t cry or make a noise. Marissa was worried. “She looked at me with this blank stare,” she said. “Honestly, I didn’t know what to do with her.”

So Marissa, a touchy-feely type who calls all the babies she helps deliver her “grandbabies,” asked the mom if she could hug her. The mother agreed, embracing her gratefully.

“One of my coworkers said, ‘Are you crazy? With COVID?’” Marissa recalled in her thick Nuyorican accent, a result of growing up in the Bronx with Puerto Rican parents. “And I said, ‘She just lost a baby. She needs a mom. She needs to know that I’m there for her, and that’s the only way I could show it.’”

The pandemic has deeply affected Americans of Marissa’s age. The risk of death from the virus begins climbing steeply for those over 50. As a Black Hispanic woman over 60 with preexisting conditions, including diabetes, Marissa would be vulnerable even if she weren’t working at a hospital caring for patients, some of whom have COVID-19. “I’m putting my life at risk,” she said, “but I’m not going to modify my nursing style or the care of the patient.”

It’s not just a fear of contracting the virus that older workers must contend with. The pandemic has also sent some of them into a financial crisis and made others choose between their health and their livelihoods. A report on the US labor market by three economists in April found that the pandemic “led to a wave of earlier than planned retirements,” causing an “exceptional decline” in the country’s workforce. Americans have been forced into retirement as jobs have disappeared and industries have collapsed, or they have simply retired due to fears of the virus’s fatality rate for older people. As unemployment skyrocketed into the tens of millions, the jobless rate of those over 55 jumped from 2.8% in February to 11.5% in May. An 84-year-old Maine woman who sought a job as a motel cleaner because her Social Security check wasn’t enough was painted as a good news story.

Overwhelmed hospitals desperately needed retired healthcare workers. The Department of Veterans Affairs received a federal waiver to rehire its retired medical professionals. Tens of thousands of retired healthcare workers volunteered to work in New York in early April when it was an epicenter for the virus.

But for Marissa, retiring was never an option. “I can't retire during this,” she said. “I’ve got to be supportive of my coworkers and my patients.”

Her daughters didn’t even consider asking her to stop working, despite the risks. “Please! It wasn’t even a topic of conversation,” her eldest daughter, Yvelle Lee, 38, told BuzzFeed News, laughing. “It wouldn't even have dawned on me to ask her, to be honest. My mom talks about how she's going to retire [eventually], and I really don't believe her. Being a nurse is to her core.”

“I can’t retire during this,” she said. “I’ve got to be supportive of my coworkers and my patients.”

But the pandemic has also taken away Marissa’s normal support network. She’s unable to see her daughters and friends for two weeks after a shift with a COVID-19 patient out of fear she will get them sick. As a single woman who lives alone and loves socializing, she knows it’s a big loss.

More fundamentally, though, as a frontline healthcare worker, Marissa has also lost her faith in her government’s ability to handle and contain a major health crisis — to protect workers like her and the patients she cares for.

As one of the national vice presidents of National Nurses United, the country’s largest nurses union, Marissa has long been a fighter for workers’ rights — but that fight feels even more urgent this year.

“This pandemic should never have gotten as serious as it has,” said Marissa. “That tells me that my country, my government, does not value my knowledge as a healthcare worker — to ignore what has been placed out there by the scientists and make it such a joke.”

This isn’t Marissa’s first experience with a deadly, mysterious virus. In the 1980s and ’90s, she nursed patients through the AIDS epidemic. That was also a time of misinformation and confusion about an unknown virus. Initially it predominately affected gay men, although high rates of intravenous drug use and poverty also meant her South Bronx hometown quickly became a hot spot. Her first healthcare job in the late 1970s had been at the Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center in New York City, close to apartments she’d grown up in. As the AIDS epidemic continued, and Marissa found herself working elsewhere, that hospital saw some of the highest infection rates in the country.

One major issue for nurses in the early days of the AIDS epidemic was that scientists weren’t yet entirely sure how the virus was transmitted, and there was concern it could be spread by touch (it’s now known it can only be transmitted through certain bodily fluids, such as blood and semen). Nurses would therefore wear a full head-to-toe covering when interacting with patients. Marissa remembers being responsible for just one or two patients during each shift, giving her time to sit and talk with them. She always had the protective equipment she needed.

The coronavirus pandemic has been a different story. “It is an everyday battle to get a N95 respirator or to have the gloves or the gown,” said Marissa.

Across the country, more than 1,500 healthcare workers have died while treating patients with the coronavirus, including almost 200 nurses, according to Marissa’s union. In May, the NNU surveyed 23,000 nurses across the US, including 2,000 in Florida, and 83% reported having been compelled to reuse masks or PPE that were only intended for a single use.

There are 242 hospitals in Florida serving the state’s population of more than 21 million people.

Osceola Regional Medical Center, where Marissa works, has 404 beds and is one of 184 hospitals across the US owned by HCA Healthcare, a Nashville-based conglomerate and the nation’s largest hospital chain.

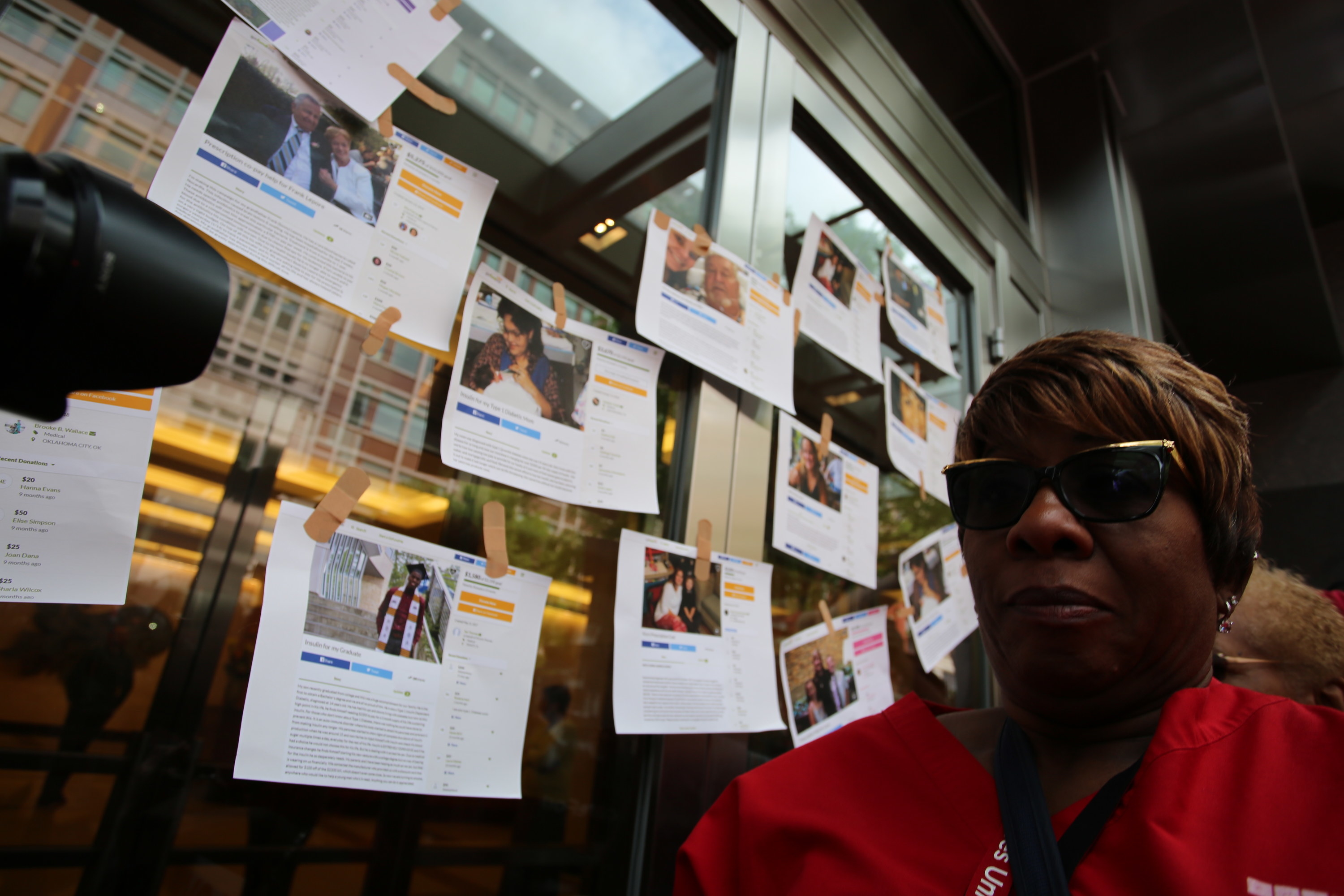

Throughout the pandemic, the NNU has been railing against HCA for laying off healthcare staff, cutting pay, and not providing enough PPE. As a union leader, Marissa led protests at her hospital on May Day. She said she feels deeply uncomfortable that she is unable to change her PPE between patients as often as she would like, and is worried it puts patients at risk of transmission. “It makes me fearful that I am not providing the same care as a nurse that I can [otherwise] provide because of the lack of equipment,” she said.

Davide Carbone, CEO of Osceola Regional Medical Center, has insisted that his team’s pandemic planning has made protecting nurses and physicians at the hospital a top priority. HCA, meanwhile, has accused the labor union of exploiting the public health crisis in order to organize more members.

“In the ’80s, we had more compassion,” said Marissa. “This is what has been lost because of corporate greed.”

Corporate greed infuriates Marissa. So does racism, sexism, misogynoir, inequities faced by Latinos, the cost of health insurance, mistreatment of immigrants, and President Donald Trump, whom she refuses to call by name and instead simply refers to as “45.” She first came to healthcare after more than a decade in the military — two years in the Army and 10 years in the Air Force — and loves to fight a good fight.

“My mom has always been an activist,” said Yvelle. “You want to see my mother get riled? [Watch] when somebody in power is abusing their power and abusing somebody else.”

Marissa channels a lot of that anger into labor organizing. She first joined a union at Bronx-Lebanon and was horrified later when hospitals she worked in didn’t have one. When she arrived at Osceola Regional in 2004, she asked for her union labor card at orientation. “They looked at me like I’d grown a second head,” she recalled. Five years later, the hospital unionized and Marissa became a union leader.

“My mom has always been an activist.”

This summer, she has been fighting against staffing shortages as cases in her area boomed. While Florida and its elderly population of retirees initially escaped the worst of the pandemic when it first started raging in the US, the state soon became a global epicenter in the pandemic after officials rushed to reopen for the lucrative summer tourist season. Gov. Ron DeSantis, a close Trump ally, was accused of sidelining experts and ignoring scientists with disastrous results.

From early July to mid-August, more than 100 people in Florida were dying every day. Marissa’s hospital had to halt elective surgeries in mid-July to deal with the surge in patients. With roughly 650,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19, Florida now has the third-highest number of coronavirus infections of any state, dwarfing those of New York, which was hit early, by more than 200,000. Only Texas and California have more. In central Florida, where Marissa lives, roughly 100,000 residents have become sick with the virus and almost 2,000 have died. In total, more than 11,000 Floridians have died in the pandemic.

Because of the unprecedented crisis, nurses and other medical professionals have been called upon to work extra shifts and often in areas or wards that they are not trained in. Marissa worries that other nurses in her delivery ward may have exposed new parents to the virus by having to work in other parts of the hospital. Testing hasn’t been as accessible as she would like, and she worries that specialist nurses like herself are unprepared to work in critical care units. “Their philosophy is a nurse is a nurse is a nurse,” Marissa said. “It’s like asking an orthopedic surgeon to do brain surgery on my father.”

In response to Marissa’s claims, a spokesperson for Osceola Regional Medical Center told BuzzFeed News it had “spared no expense” in providing the necessary equipment and supplies, including PPE, to its staffers during the pandemic. They also insisted it has strictly followed CDC guidelines for testing patients and staffers for the virus. “The team is extremely diligent about safety measures across the hospital, especially in high-risk units such as labor and delivery,” the spokesperson said. “Based on this particular colleague’s comments, it seems that she simply disagrees with the CDC on matters of COVID-19 infection control, such as the use of PPE and who should be tested in what circumstances.”

Marissa’s daughters aren’t surprised she’s been a thorn in her hospital’s side. They like to call her Hoffa Jr., after Jimmy Hoffa, the infamous New York union leader — played most recently by Al Pacino in Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman (2019) — who disappeared in 1975 and was suspected to be killed by the Mafia.

“If she comes up missing,” daughter Yvelle joked, “I'm not going to be surprised.”

There are two intrinsically linked pandemics affecting Black Americans in 2020. Whether it’s from the coronavirus or police brutality, Black people are significantly more likely to die than white people. The rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, following the police killings of George Floyd (who himself recovered from COVID-19) and Breonna Taylor, has helped highlight the systemic racism that has killed Black bodies for centuries.

Black women have been particularly affected by the turmoil of 2020. In a May survey from Essence magazine, almost half of the Black women surveyed reported knowing someone who had contracted COVID-19, and a quarter knew someone who had died from it. It’s estimated that almost 1 in 5 Black women lost their job between February and April — a higher rate than that of whites or Black men. Black and Hispanic people were much less likely to have jobs that allow them to work from home, while Black women are also strongly represented in essential work roles at healthcare facilities, supermarkets, or public transport, exposing them to a frontline risk.

But, as in other industries, Black women in healthcare are still paid substantially less than their white male peers. Black women doctors earn 73% of the hourly wage of a non-Hispanic white man in the same role, according to the Economic Policy Institute. Black women nurses like Marissa earn 82% of the hourly wage of white male nurses.

Marissa has two master’s degrees, one in nursing and the other in accounting. She insisted to her daughters: “Everybody’s going to look at you for your skin color. Prove them wrong. Get the best education you can.” Yvelle completed her own doctorate dissertation on Black women leaders in IT. She credits her mom with inspiring her to research workers’ rights and racism against Black women.

Marissa knows what it’s like to be judged as a Black woman in a professional environment, something she said was stark when she first arrived in Florida. “I face a lot of racism here,” said Marissa. “In New York, you didn't see it. It was very underlying. Here, it’s right in your face.”

She recalls that shortly after moving to Florida in the mid-1990s, the white father of one of her pregnant patients requested that another nurse care for them, despite Marissa being the most senior nurse on duty in the ward. “Is there a problem with me?” she asked.

“You’re colored,” she said the man told her.

“I’m not colored, I’m not polka-dotted, I’m Black,” Marissa recalled responding.

"Save one life and you’re a hero. Save hundreds of lives and you’re a nurse."

She then asked if he would like to speak to her superior, knowing full well that the nursing supervisor on duty was also a Black woman. “She steps in, and his face drops,” she said.

Growing up during the rise of the civil rights movement made Marissa acutely aware of anti-Black racism, the power of protest, and the importance of having Black pride. In March 2018 and 2019, on the anniversary of Bloody Sunday, she marched over the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the site where John Lewis and others were beaten in 1965. At last year’s march, she walked in the rain holding a “Medicare for All” banner, surrounded by nurses from across the country.

When Marissa found out Derek Chauvin, the former Minneapolis police officer who placed Floyd in a fatal knee chokehold, had a home in Orlando and protesters had gathered there, she immediately wanted to join but was too late. “We should have been out there,” she told her daughter. “We could have been out there marching.”

Marissa now works the weekend night shifts from Friday to Sunday, meaning she missed the Black Lives Matter protests in Orlando this summer. Still, she insisted that one of her colleagues take her favorite scrubs to wear at one of the marches. “Save one life and you’re a hero,” it reads. “Save hundreds of lives and you’re a nurse.”

Working during a global pandemic means sometimes missing out on special family moments. Yvelle is due to get married in 2021, and the wedding is tentatively scheduled for next May. Over Labor Day weekend, Yvelle had her wedding dress fitting, a chance for her mom to see her in the gown for the first time. Marissa tried to switch shifts but couldn’t get the time off due to staffing shortages. She figured instead that she would just go anyway and try to stay awake like she used to do when her daughters were in school and she’d still attend their field trips and sporting events after working a night shift.

Instead, after her grueling 12-hour shift, she drove 45 minutes back to her home in Orlando, collapsed on the couch, and slept through it. “I was disappointed,” Marissa said. “She’s getting married; I want to be part of it.”

Yvelle was upset, but more for her mom than for herself. “I legitimately felt bad,” said Yvelle. “She only has two girls, me and my sister. She did everything with my sister, and now we’re in the middle of COVID, trying to coordinate everyone's schedule. Everything has to be socially distanced. It’s made things a lot more challenging.”

“Everything has to be socially distanced. It’s made things a lot more challenging.”

Marissa and her daughters are very close. They dine together regularly — Yvelle lives a 20-minute drive away, and her younger sister is just 80 miles away in Tampa — either trying new restaurants or eating something cooked by Marissa, who unwinds from work by cooking in her kitchen.

But both Yvelle and her sister have sickle cell anemia, a blood disease that increases one’s risk of severe illness from COVID-19, according to the CDC. If Marissa has been exposed to a patient with COVID-19, she has had to self-quarantine and stay away from her daughters.

“She’s not worried about herself,” said Yvelle. “She’s worried about me and my sister.”

On a typical Thanksgiving, Marissa normally goes big, cooking up a meal for around a dozen family members and friends. Her menu normally includes two meats (turkey plus roast pork or ham), rice and peas, collard greens, sweet potatoes with marshmallows, potato salad, and then four desserts: two sweet potato pies, an apple pie, and a pecan pie cheesecake.

“Right now, I don’t know if I’m going to do Thanksgiving [this year] at all,” said Marissa, unsure if she would have to quarantine herself in order to protect her loved ones. “It’s going to be really, really sad because I’m used to a house full of people.”

Yvelle has been saddened watching her normally boisterous mom withdraw and be forced into isolation due to her job. “She was really socially active [and used to] go visit my aunt in Puerto Rico or travel with the union,” Yvelle said. “Now, it’s relegated to Zoom meetings at 8 p.m.”

But Yvelle knows her mom wouldn’t have it any other way. She’s been like this all her life.

“She really has made her mark, even during the pandemic,” said Yvelle. “When it’s all said and done, you know Marissa Lee was a healthcare worker that did the best she could.” ●