In the lead-up to Tuesday’s presidential election, 17-year-old Abby Wright has been pleading with everyone she knows in her conservative hometown of Dalton, Georgia, not to vote for Donald Trump. Too young to vote herself, she’s instead doing her part by running a mock election at school and making political TikToks to counter misinformation.

But Abby wasn’t always so left-leaning. Like countless others across the US, she found herself protesting for the first time in her life during this summer’s Black Lives Matter demonstrations and they profoundly transformed her. Her political reawakening is now the subject of her college application essay.

“Before this summer, I saw myself as a middle of the road conservative, just like my parents,” she wrote. “However, after seeing the lack of a reaction towards the injustice from one side of the country, I knew it was my time to move to the left, much to the dismay of my family.”

BuzzFeed News has journalists around the US bringing you trustworthy stories on the 2020 Elections. To help keep this news free, become a member.

In this election year, the US has found itself grappling with two pandemics: the coronavirus and institutional racism. Much has been written about how the president’s handling of COVID-19 has influenced voters, but many others have also been swayed by the Black Lives Matter movement. Reignited again this year by the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, BLM has emerged as the civil rights movement of the 21st century. On June 6, more than half a million people turned out to have their voices heard at 550 demonstrations across the US, according to data published by the New York Times. Somewhere between 15 million and 26 million people have attended at least one BLM protest this year across the country, making it the biggest social movement in history.

Swept up in this movement were people like Abby who found themselves compelled to protest for the very first time. Many are now casting their ballots for president, still energized by their experience.

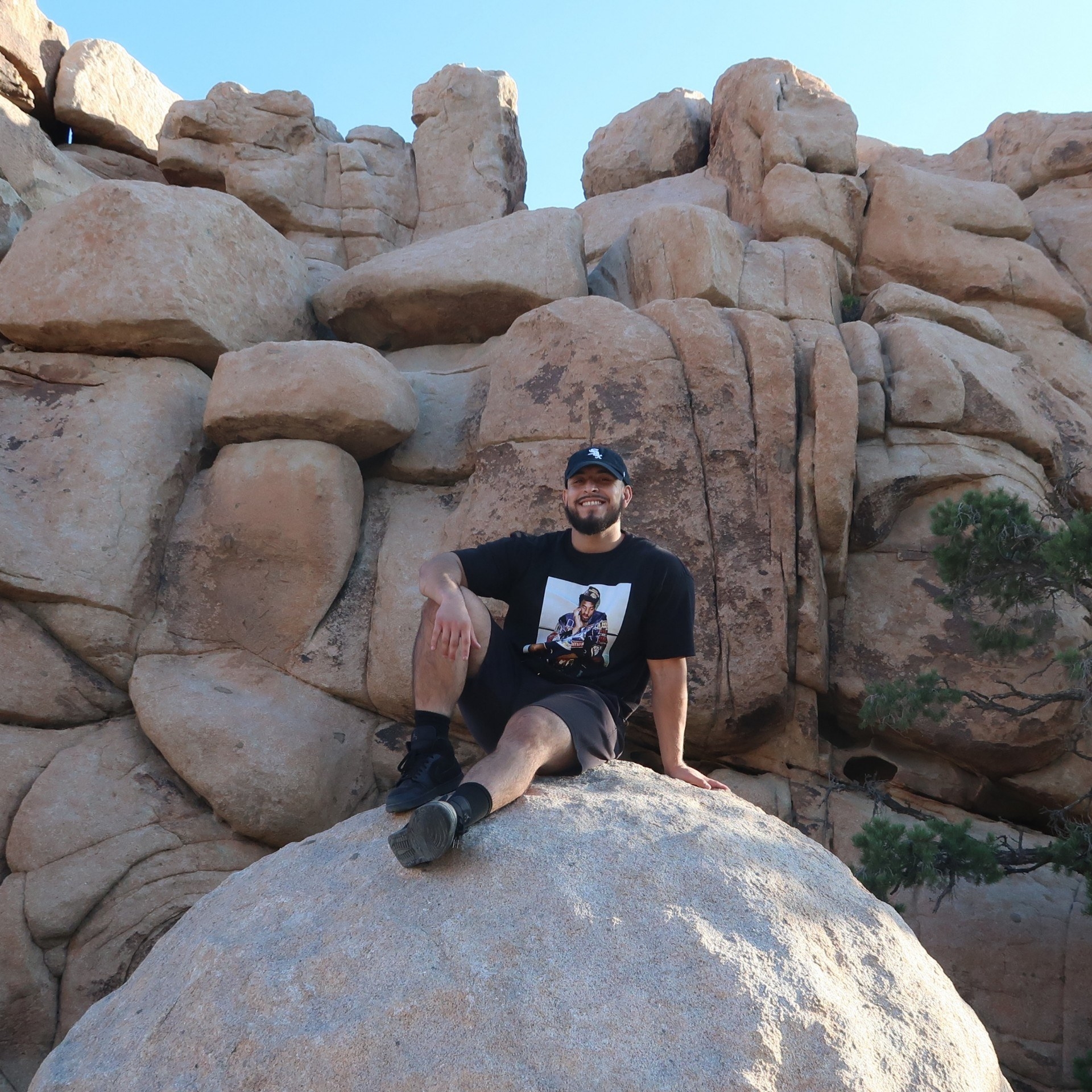

“I was kinda on the divide about voting,” said Josh Luna, a 27-year-old former military officer in Los Angeles. “But the way things went with the riots, I was like, All right, I'm going to vote for sure. That was the pushing point.”

Luna attended his first-ever protest just five days after Floyd’s death, arriving alone to a rally about 30 miles east of where he’d grown up as the child of Mexican immigrants in La Puente, California. He said he was horrified by what he described as a police response that was excessive and indiscriminate.

After attending several more demonstrations, last week he voted early for Joe Biden. “You could see which side cared about the Black Lives Matter movement,” said Luna, “and which side couldn't embrace it.”

Biden has walked a careful line when it comes to the BLM movement. He has acknowledged the existence of institutional racism and delivered a video address at George Floyd’s funeral calling for racial justice. But he has also gone to lengths to distance himself from the riots and violent civil unrest that some on the right have pointed to in order to tarnish the entire BLM movement. When asked just this week about the protests in Philadelphia following the police shooting of Walter Wallace Jr., a Black man experiencing a mental health crisis, Biden immediately responded by declaring, “What I say is that there is no excuse whatsoever for the looting and the violence.”

But first-time protesters who spoke to BuzzFeed News said they saw any vote for Trump — who has refused to denounce white supremacy, sent federal officers to dispel protesters across the country, and suggested “thugs” who were looting after Floyd’s death be shot, all the while claiming he has done more for Black Americans than anyone since Abraham Lincoln — as a direct affront to the BLM movement that has been so important to them personally.

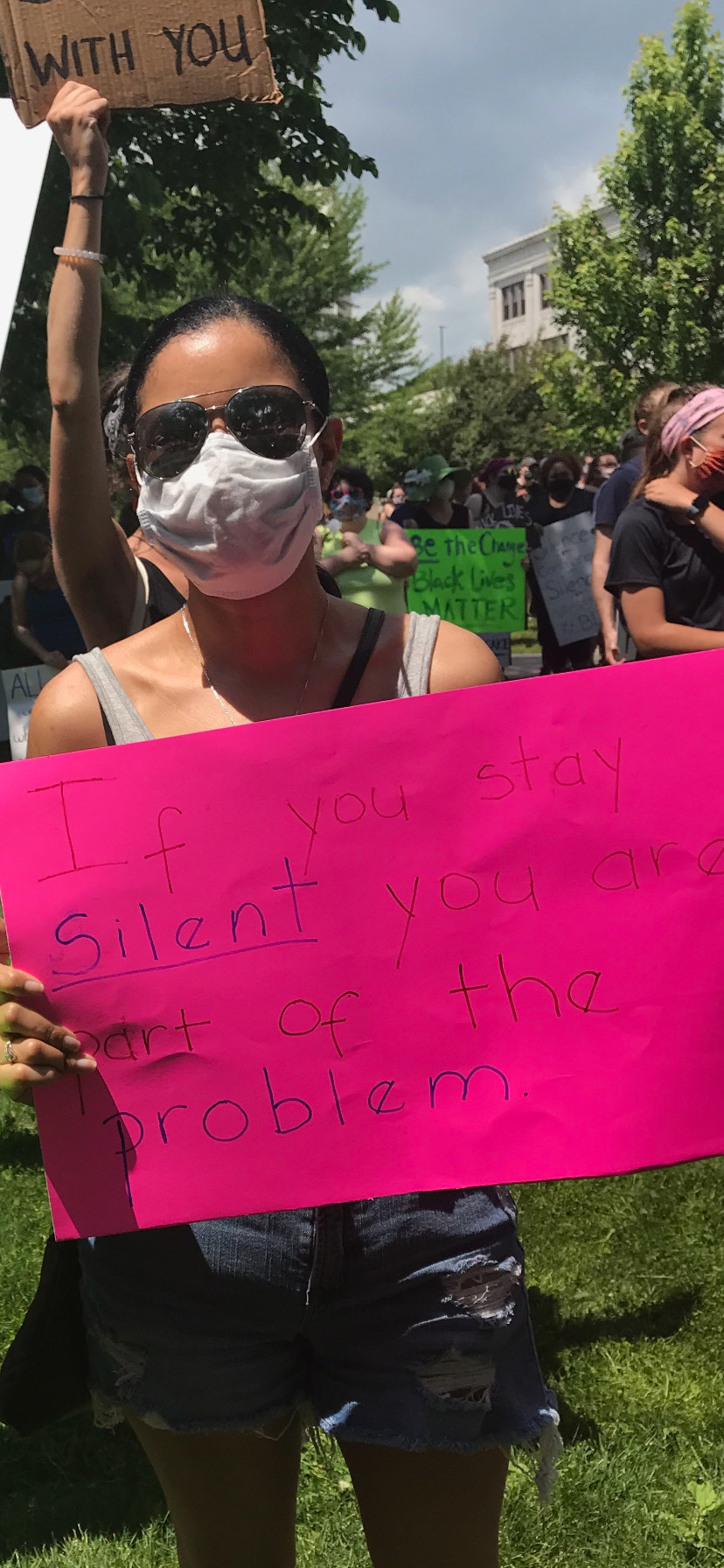

“It’s hard to fathom anyone wanting to vote for another four years of Trump if you believe that you're not a racist, if you believe that Black lives do matter,” said Lisseth Hazim, a 31-year-old single mother in upstate New York. “I’ve just started seeing the hypocrisy in a lot of people.”

If you have a news tip, we’d like to hear from you. Reach out to us via one of our tip line channels.

On Wednesday, Hazim voted in her very first presidential election, lining up for one hour in her home in South Glens Falls, New York, to cast a ballot for Biden. She even volunteered for Tedra Cobb, a Democrat challenging her local Republican lawmaker for the House of Representatives, something she’d never previously considered doing. “Because of the BLM movement, I felt I needed to push my comfort level and do it because it’s important,” said Hazim.

Central figures in the BLM movement have been urging supporters to take their march from the streets to the polls. On Thursday, Tamika Palmer, the mother of Breonna Taylor, appeared at a Chicago rally with other families of victims of police violence against Black people. “We've been crying, we've been protesting, we've been in the courts,” Palmer said. “But unless we vote, we will not get the change that we need.”

Not all those who participated in the protests are old enough to vote, though, so some are finding other ways to be politically active. “Because I can't vote, that’s even more of a reason to try and convince others to vote and tell my friends who are 18 to get registered,” said Anna Villard, a 17-year-old rising senior from Surprise, Arizona.

After attending half a dozen BLM protests in Mesa and Phoenix in recent months, Anna has been registering people to vote at her high school, making designs and posters for ballot boxes, and updating her Instagram bio daily with the number of days left to register to vote and until Election Day. She has even been searching voter registration records for her teachers and quizzing them about it. “I’ve been asking my teachers, ‘Are you registered to vote? Have you turned your ballot in yet?’ I think it’s caught them off guard, too.”

Anna, who is Black, said the movement has given her more courage to call out racism. When girls from her school used the n-word online, she reported them to a volleyball coach and the principal. She’s also unfollowed people she knows on social media who follow the president and no longer feigns politeness to her Trump-supporting neighbors. “I’m not going to associate with someone who has Confederate flags in their garage,” she said, “and if that’s a problem, I'm sorry.”

Trump repeatedly complains that the media focuses on “COVID, COVID, COVID” this election, but Paige Dominguez, a 43-year-old preschool teacher from Carlsbad, California, sees a link between the treatment of Black Americans and people wearing masks to help prevent the spread of the coronavirus, which has disproportionately affected Black and brown communities. “There’s a good case study that could be done comparing the way people are reacting to COVID and people are reacting to the Black Lives Matter movement,” said Dominguez. ”It just comes down to caring about your neighbor.”

Dominguez is frustrated that churches in her area are hosting events for Republicans and not doing more to vocally support BLM, especially because she believes churches should fight for the oppressed. She found attending a BLM protest for the first time a deeply moving, almost spiritual experience.

“I could feel the leaders of the chants, feel their passion, it really resonated with me,” said Dominguez, who is white and attended because her teenage daughter begged to go. At first she feared chanting but soon felt compelled to join in the protest chorus. “I had to rise up with them too,” she said. “If I hadn't been part of the march, I wouldn't have been affected as much.”

Hazim, the upstate New Yorker, says her newfound activism has changed her profoundly. After attending a BLM protest and changing her Facebook profile photo to read “Black Lives Matter,” she now quizzes men on dating apps about their support of the movement and which presidential candidate they support.

But perhaps her most personal change has been how the protests made her rethink one of the most monumental events in her life.

When she was a child, Hazim grew up in the Bronx and the Dominican Republic. When she was 6, her father, Jorgiris Hazim, was shot and killed by NYPD narcotics cops during a raid related to drug dealing. Her stepmother had always told her that her dad was asleep when police busted in. A Daily News story a month after her father’s November 1995 death reported that the two officers involved were under investigation for the shooting and that “investigators reportedly found no weapon or drugs inside the sixth-floor apartment.” They were never prosecuted.

For years, Hazim, who is Black and Latino, had avoided telling people about her father’s death, ashamed of his actions and convinced that he was a “bad guy” who must have deserved it. But after participating in protests for the first time, she now wonders how an unarmed man could be killed in his home with his family nearby in the middle of the night.

“After the George Floyd incident is really when it all hit me,” said Hazim. “Just knowing how my dad wasn't given the fair proper channels to plead his case, maybe pay for his crimes in a different way, because of the color of his skin.”

“All these years I've had a first-hand experience of how cops treat people of color,” she said, “and I didn't even realize it.” ●

Correction: The city of Dalton, Georgia, was misspelled in a previous version of this story.