Schools around the US have put a patchwork of defenses into place against a constant and singular threat: guns.

How do you defend a packed classroom against someone intent on opening fire on it? In one Pennsylvania school, it’s a bucket of river rocks to throw at a shooter. In Littleton, Colorado, it’s constant video surveillance. In Texas, it’s the deputy governor’s suggestion that schools need fewer doors.

Since the Columbine shooting in 1999, schools have both bought expensive new products and have suggested untested, sometimes kooky, policies. Though 2018’s Parkland shooting renewed efforts for new gun control measures, schools aren’t waiting to see if those laws change.

Some districts put a stronger emphasis on trying to stop a potential shooter before they can pick up a weapon; others spend millions of dollars hardening campuses for when he does. There’s no reliable data on how effective this all is.

But since 1970, there have been 732 people killed, including assailants, in all types of shootings, from kindergarten through high school. And so far, all of these tactics haven’t slowed the bloodshed since Columbine.

There’s no clear solution. And in the search for one, students around the country are wearing bulletproof backpacks, looking through bulletproof glass, and learning “stop the bleed” programs. It’s part of their daily lives.

Below, BuzzFeed News breaks down many of the products, policies, and programs being adopted or suggested to build a fortress around students, teachers, and school staff with one clear intent: preventing them from getting shot.

Opinions about how to stop school shooters are vast and varied. Some experts advocate for hardening schools as much as possible; others say active shooters are less of a threat than the public realizes.

Steve Satterly

30-year educator

Analyst with the Safe Havens International nonprofit

“We’re coaching schools to not focus so much on active shooters.” Instead, Satterly’s group trains staffers to handle natural disasters, a student threatening to kill themselves, or a medical emergency. “There is less than 1% chance that a person in a school will ever face an active shooter situation.”

Amanda Klinger

Director of operations at the Educator’s School Safety Network“School security is a billion-dollar industry. Folks are making a lot of money off this stuff. We can’t just add law enforcement strategies, that’s what we’ve been doing since Columbine and it hasn’t solved the problem. An aftermarket door lock only helps in a school shooting — it doesn’t help bullying. ”

Lori Alhadeff

Cofounder of the Make Our Schools Safe organization

Broward County school board member

Mother of Alyssa Alhadeff, 14, killed in Parkland

“We need to go about this with layers and layers of protection. Your school does not need to look like a prison, but there is a lot of things we could do to create a safe environment. What we did in the past — guess what, it didn’t work. My kid is dead, and 16 other people are dead.”

Desmond K. Blackburn

Former superintendent of Brevard County, Florida

Member of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Commission

CEO of the New Teacher Center nonprofit

“I don’t know how many situations exist in the security world where the potential ‘threat’ is in the cohort of people you’re actually protecting. During all this education and training of what to do in the event of a shooting, the chances are the next school shooter is a current child who is listening to and hearing this education and this training. It makes it very difficult and complicated.”

Marcel McClinton

17-year-old senior at Stratford High School in Houston

Member of the Mayor's Commission Against Gun Violence in Houston

Survived a mass shooting next to his church in 2016

“These adults think so strongly that these things will help, and we’re avoiding the clear issue: our gun policy. People keep saying hardening schools is going to protect our kids, but that’s putting a Band-Aid over a massive laceration.”

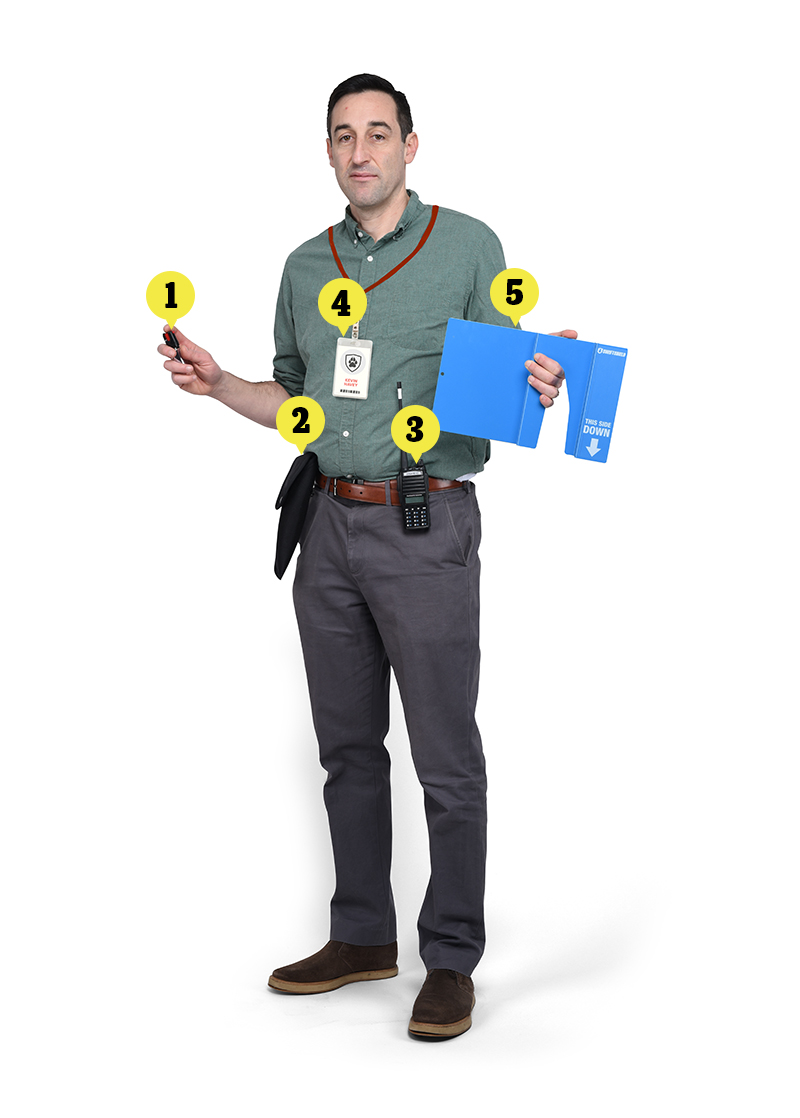

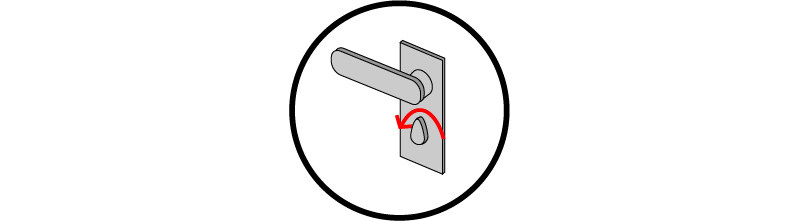

Auto-lock doors

No school shooter has breached a locked interior door — usually they just keep walking. The Sandy Hook Advisory Commission said all classroom doors should be able to be locked from the inside, but it’s costly. “Each commercial-grade classroom lock costs $300 to $600,” Satterly said. So many schools just insist teachers keep doors locked during class time. Other schools are introducing electronic systems that automatically lock all classrooms in a crisis.

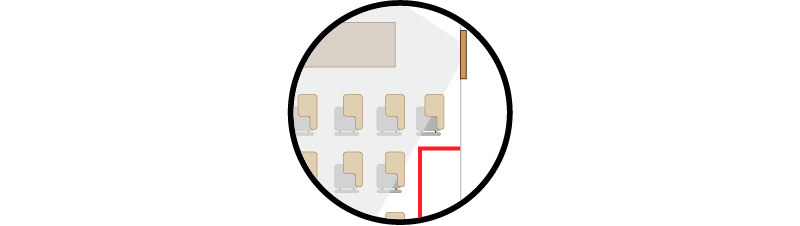

Hard corners

The Parkland shooter didn’t enter classrooms, but shot through the door’s glass pane. That’s how Alyssa Alhadeff died. Her mother advocates for marked safe areas, or “hard corners,” that can’t be seen from a door or window: “If Alyssa was empowered to know where to go, knew where the safe zone was — with red tape or some type of coding system,” she would have “not been in the direct line of sight.” Other Florida districts adopted hard corners, but some parents said their children called the thick black and yellow tape "anxiety lines." “It’s an immediate reminder that we believe that somebody could come in it at any time and shoot up their campus,” said Jennifer Sabin, a public education advocate in Polk County.

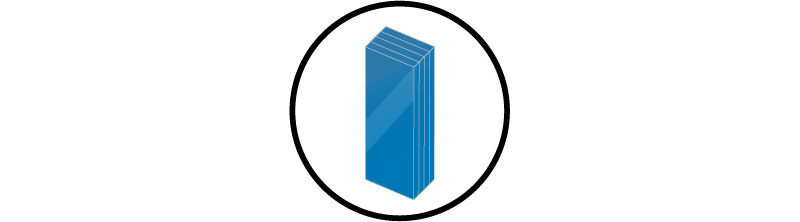

Bulletproof door panes and windows

The Sandy Hook assailant entered the school by shooting through the glass of locked doors. Since then, thousands of schools have installed tougher panes. The glass is never completely bulletproof — it can take over 10 minutes to shoot through — and is one of the most expensive school safety improvements, with a full door costing more than $1,000.

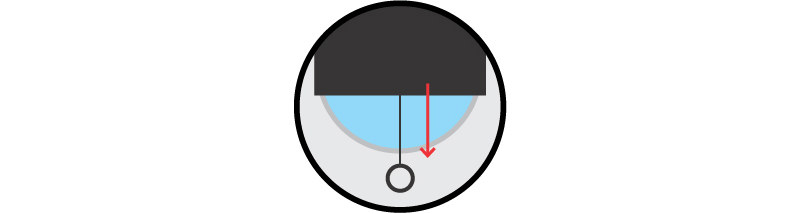

Door shades

The first classroom the Sandy Hook shooter approached was unlocked but had a blackout screen pulled down over the window — and the gunman moved on. A shade relies on a teacher actively covering the window during a lockdown.

“Stop the Bleed” kit

The kits, developed by the Department of Defense and the American College of Surgeons, contain tourniquets, dressings to enhance blood clotting, and compression bandages. Alhadeff believes the kits should be standard in public buildings, like heart defibrillators.

Panic buttons

New Jersey’s "Alyssa's Law," passed in honor of Alhadeff, requires all public elementary and secondary schools to have an emergency panic button in each building that alerts local law enforcement. The silent alarm also sets off an emergency light on the outside of the building. The intent is to get police to schools faster by alerting them more quickly.

Security cameras

More than 80% of schools use security cameras, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Traditionally cameras are more for creating a record than preventing attacks. But in Colorado’s Littleton public school district, trained security officers monitor 1,200 cameras — up from the 475 cameras in 2015 — every hour of every day. The cameras offer color and pattern recognition — if someone suspicious is wearing a red jacket, the cameras can find anyone wearing red — and new updates are expected to offer facial recognition for students.

Social media surveillance

Many districts pay companies or use their own staff to monitor public student social media for troubling keywords. But kids also troll officials by writing words they know will activate security alerts. “The minute they know we’re monitoring, they start putting keywords in. I probably would have done the same thing as a kid,” Grace said.

Monitoring school computers

If students use school-issued computers, staff can easily monitor what’s on them. Students in Littleton, for example, are all given a Chromebook, and monitoring programs can alert for troubling words or signs of distress. “If you are flagged, we’re going to search that district property remotely — in your folders and check your Google documents,” Grace said, pointing out that they’ve found and helped students writing on their school computers about self-harm.

Visitor management systems

Thousands of schools use management systems such as Raptor to check people in. Visitors have to provide identification, their details are recorded, a photo taken, and their driver’s license searched through a sex offender database.

School resource officers (SROs)

The latest National Center for Education Statistics show that 57% of public schools had one SRO — sworn armed law enforcement officers, usually an armed local police officer or sheriff’s deputy — or private security guard on campus. Results have been mixed. In May 2018, an SRO stopped a student who brought a rifle to graduation practice in Dixon, Illinois. The SRO at Santa Fe High School confronted the shooter, but the official was shot and critically injured. At Parkland, the SRO was the only armed officer on campus and he didn’t enter the school building during the shooting. And more, armed officers will likely negatively impact black students, who are disproportionately arrested by school officers. “People don’t talk about the school-to-prison pipeline, and that to me is also huge,” McClinton said.

Anonymous alert systems

These offer students or the public a way to tell authorities — via apps, phone numbers, or websites — about anyone they fear may harm themselves or others. Some states use a single tipline: Michigan has OK2SAY, Wyoming and Colorado both use Safe2Tell, Utah has SafeUT and Nevada has SafeVoice. Colorado introduced its Safe2Tell program in 1999 after Columbine, but it wasn’t until the Arapahoe High School shooting in 2013, when a male student armed with Molotov cocktails, a shotgun, and a machete killed one student before security stopped him, that Littleton students widely embraced the system. “The biggest detection you have is the other kids you have,” Guy Grace, director of security and emergency planning for Littleton, Colorado public schools and chairman for the non-profit Partner Alliance for Safer Schools. “With Safe2Tell, we’re getting screenshots and other intelligence straight from the kids.”

Fewer entrances

“We may have to look at the design of our schools moving forward and retrofitting schools that are already built. There are too many entrances and too many exits,” said Texas Lt. Gov Dan Patrick after the 2018 Santa Fe High School shooting. Many schools have implemented a single entry point in recent years, including Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, but that shooter gained access as the exits were opened for dismissal.

Metal detectors

Metal detectors have been used for decades to stop guns, knives, weapons, and drug paraphernalia from entering schools. But research on the effectiveness of metal detectors is inconclusive. In 2015, just under 6% of high schoolers had daily metal detector screenings. But research on the effectiveness of metal detectors in reducing violence is inconclusive. During the 2005 shooting at a Minnesota high school, the gunman killed an unarmed security guard working the metal detector. Klinger says she’s worried about the impact of screening on children, saying “it feels different” and “impacts academic achievement.”

Smoke cannons

In 2014, Southwestern High School in Shelbyville, Indiana, installed a $400,000 security system that included automatic locking doors, panic buttons that connect to the Sheriff’s Department, bulletproof glass — and a smoke cannon system. Authorities can set off smoke cannons in the hallways ceilings to disorient a shooter and try to guide them in a particular direction. The district declined to comment when asked if the school has ever activated the smoke cannons in a crisis situation.

Facial and fingerprint recognition technology

Biometrics technology hasn’t been widely adopted in schools yet, although some use electronic systems for kids to pay for lunch using a fingerprint scan. Littleton’s schools ran a fingerprint ID pilot in 2014, Grace said, and while it was logistically successful, parents didn’t embrace it. “I plan to revisit it, and come up with a way that’s not a political nightmare,” he said. But there are concerns that facial recognition technology is currently far less accurate at correctly differentiating between people of color.

Fences/security gates

Building high-security fences around a school sometimes unnerves parents and local residents. “People say, ‘fences look ugly, I don’t want kids to think they are in a prison,’” said Frank Quiambao, director of the National Education Safety and Security Institute (NESSI) at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, before adding that they were an effective — although expensive — way to limit outsiders entering.

Gunshot detectors

Like a fire alarm for gunshots, detector systems monitor audio waves and immediately alert authorities and activate cameras when a shot sounds. One such product, ShotSpotter, is used by police departments and as well as at over 2,000 school campuses. For McClinton, gunshot detectors are one of the few physical school security options he encourages because of how critical the minutes after a shooting are for survivors — and they’re not obstructive for students. “In a shooting, officers arrive and don’t know where the hell to go. These instantly tells you where the shot happened,” he said.

Notification systems

Many schools use alerts sent by app, text message, or email informing the community of an active shooter and how to respond, such as keeping away from the school or going into lockdown.

Threat assessment teams

A 2004 joint report from the Secret Service and the Department of Education said school shooters often displayed troubling behavior before an attack and encouraged schools to create teams to identify and monitor students who may harm themselves or others. These teams are made up of school staff such as a principal or school counselor — but also outsiders, such as representatives from child welfare and local police. The Oregonian reported on one high schooler who was monitored by his school’s threat assessment team after a librarian heard a friend mention some people called him “Shooter” because he was “weird.” Without any evidence against the student, he was subjected to random searches and interviews with police and was barred from carrying scissors and wearing his favorite coat — and he eventually dropped out of school.

Department of Homeland Security training programs

DHS released a set of training materials for school administrators in late 2018 aimed at building “campus resilience.” DHS also encourages the “Run, Hide, Fight” program in schools, even though its own 2018 K-12 school security guide says “it may be inappropriate to teach young children, particularly elementary school students, to fight an active shooter.”

Lockdown

Schools can implement different lockdown levels based on the risk. In a controlled lockdown — each school will likely use different labels — perhaps no one is allowed to enter the school due to a disturbance in the neighborhood but people are allowed to move within the building. In a complete lockdown, teachers and students bunker down in locked classrooms, pull down blinds, and hide in hard corners. Marjory Stoneman Douglas still conducts regular lockdown drills, which Hogg calls “completely nerve-wracking for everyone” since the 2018 shooting. “If we aren’t crying from PTSD, we’re looking at each other saying, “what is the point of this” ’cause we’ve been through this and we know it [lockdown training] doesn’t work.”

Vulnerability assessments

Officials hire outside safety consultants or have a trained staff member evaluate the particular weaknesses — it can be infrastructure or the school’s culture.

“ALICE” training (Alert, Lockdown, Inform, Counter, and Evacuate)

The most famous safety response program was created by former police officers after Columbine who wanted schools to handle an active shooting proactively, rather than just waiting for authorities to arrive. The “counter” component directs people to distract or confuse a shooter through noise or movement rather than directly fight them.

Stop the Bleed training

This first-aid training program teaches students and staff how to stop people dying from blood loss, inspired by US military training in Iraq and Afghanistan. In the Littleton school district, any child over 11 can get free Red Cross CPR and Stop the Bleed training.

Student and teacher photos by Kate Bubacz / BuzzFeed News; Portraits by Claire McCracken for BuzzFeed News; Training illustrations by Jay Keeree for BuzzFeed News; Classroom icons by Ben Kothe / BuzzFeed News.