In Knight of Cups, Christian Bale's character is a successful screenwriter who never seems to get around to writing anything. He does, however, spend time in picturesque contemplation in the desert or on a beach, takes rides in his convertible, and goes to parties.

There's an impromptu soiree he attends early on in the film, the sort of shindig that can only exist onscreen — because even the most meticulously doormanned real-life event will never look as good as it does through the scope of Emmanuel Lubezki's matchless cinematography. It's at a rooftop bar, and there's a pool and a dazed-looking model drooping in silver body paint and angel wings. The floor is covered in glitter. Rick (Bale) gets so trashed that he sprawls across a bench like a child being tumbled into bed by an invisible parent. Then the film leaps forward a few hours, when most of the attendees have left, and Rick is alone, staring out over the city, pensive — he hasn't left the party, but the party's left him.

Knight of Cups is a Terrence Malick movie and, like other Terrence Malick movies, it is lyrical, unbearably lovely, and not terribly concerned with straightforward storytelling. The characters speak in voiceover more than they do to one another; the film is one long, experiential montage set to classical music more than it is a series of chronological events. Knight of Cups is about how Rick visits and revisits a series of current and ex-lovers, friends, and family members played by the likes of Cate Blanchett, Freida Pinto, Wes Bentley, and Natalie Portman, among others, each of whom corresponds to a tarot card and each of whom tells Rick about himself and his quest for meaning in bursts of abstract prose. It's an ecstatic fantasy about feeling malaise in a Los Angeles in which all doors are open to you.

The rest of the movie is — like that shot of Rick après-party on the roof — full of equal parts beauty and bullshit, reveling in a heavily romanticized version of Hollywood superficiality while indulging a character who just can't figure out what he wants, and who bears wounds from an estranged father and a brother who died, keeping him from making connections. This doesn't stop him from trying various women on for size as possible salvation. "You don't want love. You want a love experience," one girlfriend, played by Imogen Poots, murmurs to summarize the emptiness of their relationship. Knight of Cups might be described, similarly, as an angst experience, delivering a simulacrum of a man's search for meaning as he soaks up the delights of the plush purgatory Malick makes L.A. out to be: an endless corridor of cocktails, palm trees, and lithe ladies. It's not exactly the director's Entourage, but it might be his attempt at a BoJack Horseman.

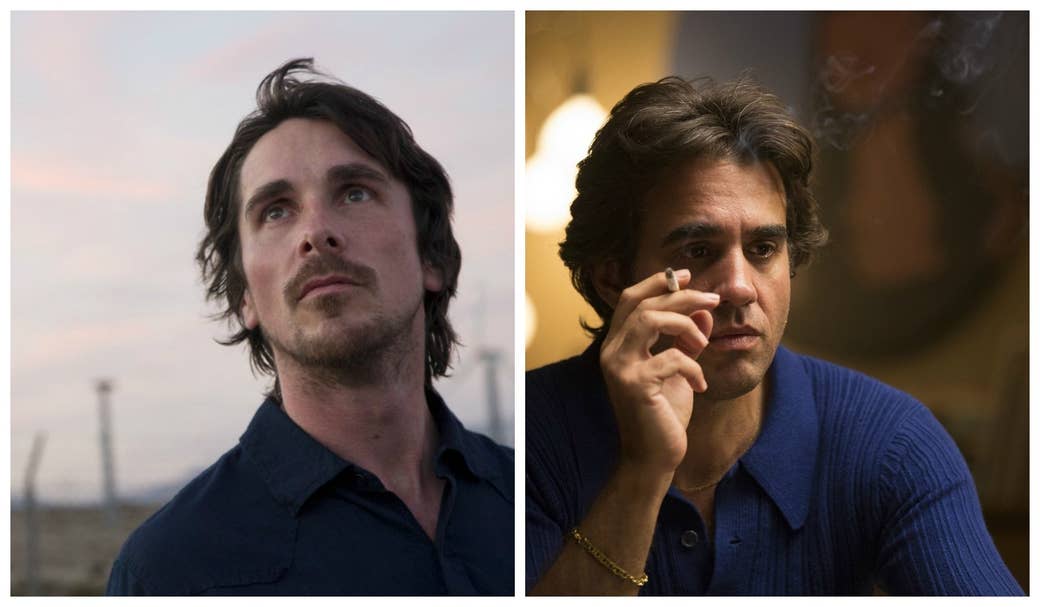

Or maybe it's his Vinyl. Malick's movie is dreamy and disconnected while Martin Scorsese's HBO series is amped up and motormouthed. But they're both auteur projects about a particular flavor of dissatisfaction that almost no one has the opportunity to sample: the unplaceable ache of having everything except fulfillment. Knight of Cups' Rick and Vinyl's record exec Richie Finestra (Bobby Cannavale) aren't the first fictional characters to feel sad in positions of showbiz power — and they won't be the last — but these explorations of their dissatisfaction are particularly nettling because there's so little about their grandeur that feels earned. Richie is disaster with a good ear, and Rick may or may not be a good writer, but whether they deserve their plum gigs is beside the point. They could share a self-pitying shuffle from their sweet perches, which are separated by a continent and a few decades but both surrounded by other people who seem to actually know what they want and what they haven't been able to get. What to give the guy who has it all? Apparently, an extravagant ode to how hollow they feel inside as they rattle around their airy condo or Greenwich house, gazing at the women who are failing to make them whole inside.

Those women in Knight of Cups — Poots' manic pixie dream girl, Teresa Palmer's stripper with a heart of gold, and Blanchett (a standout) as Rick's physician ex-wife, among others — serve as mirrors in which Rick observes his own restiveness. But in Vinyl, a series overstuffed with acting talent and grindingly short of worthy ideas, there are actual full-fledged other characters, and almost any one of them would be a more interesting center than Richie. These include Juno Temple as the punk Peggy Olson to Richie's Don Draper; or Ray Romano as Richie's aging head of promotions; or Ato Essandoh as the blues artist Richie picked up and then betrayed early in his career. Then there's Olivia Wilde as the former Warhol girl whom Richie married, a woman dealing with the fact that being a suburban homemaker can be just as thankless as being a muse.

In the pilot, they all get dragged into the maelstrom of Richie's midlife crisis when he decides against selling his label, an exchange that would have made him and his partners very rich while allowing them to offload a floundering company. He screws his partners over without asking after coming out of an eventful night with a renewed fervor for rock and roll that's only partially fueled by all the cocaine he's been hoovering. He's eager to excavate his old dreams, everyone else's desires be damned, indifferent to just how many people in his orbit haven't had a shot at their own.

While Richie sneers down at the prospect of terminally square German investors buying his company for gouts of money and frets over "selling out," Rick wanders the lobby of a sleek skyscraper listening to a man in a suit talk about how he's going to make Rick rich and then some. "Is there anyone you want to sit in a room with?" he asks. "Is there anyone you want to know?" Outside, another man in another suit compares his life to "playing Call of Duty on 'easy' — I just go around and fuck shit up," a declaration of privilege so on the nose it's almost wince-worthy, even in a movie in which wealth is just another thing these character need only say "yes" to. But the question's inescapable: If these men are living life like they have the cheat codes, why are theirs the stories that we're watching?

In the end, it's not oblivious navel-gazing that makes Vinyl and Knight of Cups' stories tiresome. It's the way that they reinforce the importance their main characters have already assumed for themselves. Knight of Cups starts with the Hymn of the Pearl, a parable from the Acts of Thomas (from the gnostic Bible) about a prince who's sent on a quest to retrieve a pearl but instead forgets who he is and why he's on a journey in the first place. In the film, Rick would be that prince, awakened from his complacent haze by an earthquake — the earth literally shaking him into awareness. In the TV show, Richie gets his own local disaster as personal epiphany when he survives a building collapse during a particularly dizzying New York Dolls show. He emerges from the rubble in a shot that feels like a nod to the end of Scorsese's own After Hours, eventually making his way back into his office bloody and dusty and claiming to have been mugged by God — though, in Richie's words, "I took his wallet instead."

These characters are not actually touched by the divine, but they accept these larger moments as signs meant for them in the same way they take for granted their access, power, and wealth. There's a chilly realism in that, even with the hallucinatory touches both Scorsese and Malick drop in to depict their protagonists' unmoored inner selves (like the vision of Janis Joplin belting a song alongside Richie's frustrated howl when his office catches on fire, or when an actress in full Marie Antoinette garb walks near Rick through a "city street" of a studio backlot). Why would Rick or Richie have any reason to doubt their places at the center of their respective universes? They're not the most compelling people onscreen, and yet they're the characters these self-serious stories are focused on. Everyone else is left on the sideline, hoping that someday they'll get a chance at the spotlight.