Contrary to what some of her former employees have insisted, Elizabeth Holmes does, in fact, blink. She just doesn't seem to do it very often. You can watch for it in the ads that documentarian Errol Morris directed for her company, Theranos, back when it was still a hot startup and not an even hotter exemplar of Silicon Valley delusion. She blinks reluctantly, with such vaguely reptilian slowness that it really does seem like she'd opt out of the basic bodily function if she could, in order to better maintain unbroken eye contact with whoever she's speaking to. And in lieu of a person, she'll stare down the camera with equal intensity.

"People don't even know that they have a basic human right to be able to get access to information about themselves and their own bodies that can change their lives," she intones in one spot, in that deliberate baritone, eyes wide and lit with a ring light that makes her fervor more uncanny. Most CEOs try to position themselves as funny, down-to-earth, on-the-level types when they appear in their own marketing material — no soulless captains of capitalism here! But Holmes leans in the opposite direction, more cult than cult of personality. She looks like a zealot, or maybe a dystopian dictator in a sci-fi movie, beaming mandatory messages of assurance into the homes of her citizens.

If you aren't already familiar with Holmes, the tech world's most fascinating fraud, the tldr goes like this: She founded a startup, Theranos, at the age of 19, dropping out of Stanford and raising hundreds of millions to create a device she claimed would revolutionize health care. It would be able to run hundreds of labs off of a fingerprick's worth of blood, and it would be everywhere, from homes to battlefields, making medical information more accessible and affordable.

It was a dream that nabbed Holmes Ted Talks, magazine covers, and headlines proclaiming her the next Steve Jobs. The fact that the machine Theranos developed never came close to working as promised didn't prevent her from making deals to provide testing to live patients, with notoriously unreliable results. In 2015, she had the No. 1 spot on Forbes' "50 Richest Self-Made Women" list; in 2018 she was indicted on charges of defrauding investors.

But you don't need to hear this from me. You can choose from a multiformat array of tellings of the Theranos tale. March 18 sees the premiere of The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley on HBO, a documentary from Oscar-winner Alex Gibney, who's become an expert in churning out serviceable nonfiction examinations of grifters, cheaters, and institutional corruption and abuse. In 2005, he made Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room, a doc about the notorious collapse of the Texas-based energy company at which, in the kind of detail too good to be made up, Holmes' father once worked as a VP. The Theranos story fits almost too well into his formula, with reenactments bridging the gaps where the talking heads and the footage of Holmes gliding through the halls of an office complex stops.

Perhaps you already caught the two-hour 20/20 special on Holmes that aired on ABC Friday, a follow-up to ABC Radio’s The Dropout, a six-episode podcast hosted by correspondent Rebecca Jarvis that premiered in January. Preceding all of this, of course, is the 2018 book Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup, the definitive document of Theranos gawking. It's the work of journalist John Carreyrou, whose investigative reporting on the company in the Wall Street Journal brought about its eventual downfall. Before Theranos really started to implode, he would be held up internally as an adversary to innovation, with employees chanting "Fuck you, Carreyrou!"

To consume any or all of the Theranos retellings is to begin to feel that Holmes' true calling was not to become a visionary, but to become a vector of content.

It's a detail that will presumably make it into the forthcoming movie adaptation — rights to the book were snapped up in a bidding war before it was even published, with The Big Short's Adam McKay set to direct and Jennifer Lawrence, perfectly age-appropriate for once, to play Holmes.

Will our appetite for all things Theranos remain unabated while we wait for the scripted project to hit theaters? There's really no reason to believe otherwise. Bad Blood was a New York Times best-seller, The Dropout topped the iTunes charts, and The Inventor looks poised to make a splash. During her meteoric rise, Holmes was very good at telling people what they wanted to hear, and at turning herself into the perfect bait for a certain kind of glowing media coverage — a woman breaking into the boys club of STEM, a once-in-a-generation genius leading us toward a better future, a figure tearing down established industries in order to effect social change and put more power in the hands of the public. It feels only fitting that her fall has made her an even more irresistible subject — an illustration of Silicon Valley hubris, an archetype for the dark side of disruptor culture, a target for armchair diagnosis, and an apparently boundless source of schadenfreude.

To consume any or all of the Theranos retellings is to begin to feel that Holmes' true calling was not to become a visionary, but to become a vector of content. At a time when we're enraptured with reexamining events to look at how media portrayals and commonly accepted narratives went awry, hers is an ideal story. It's juicy, damning, and rife with so many potential readings about what her rise and fall all meant, and what we can learn from it, that it's the perfect fuel for our 24/7 take economy.

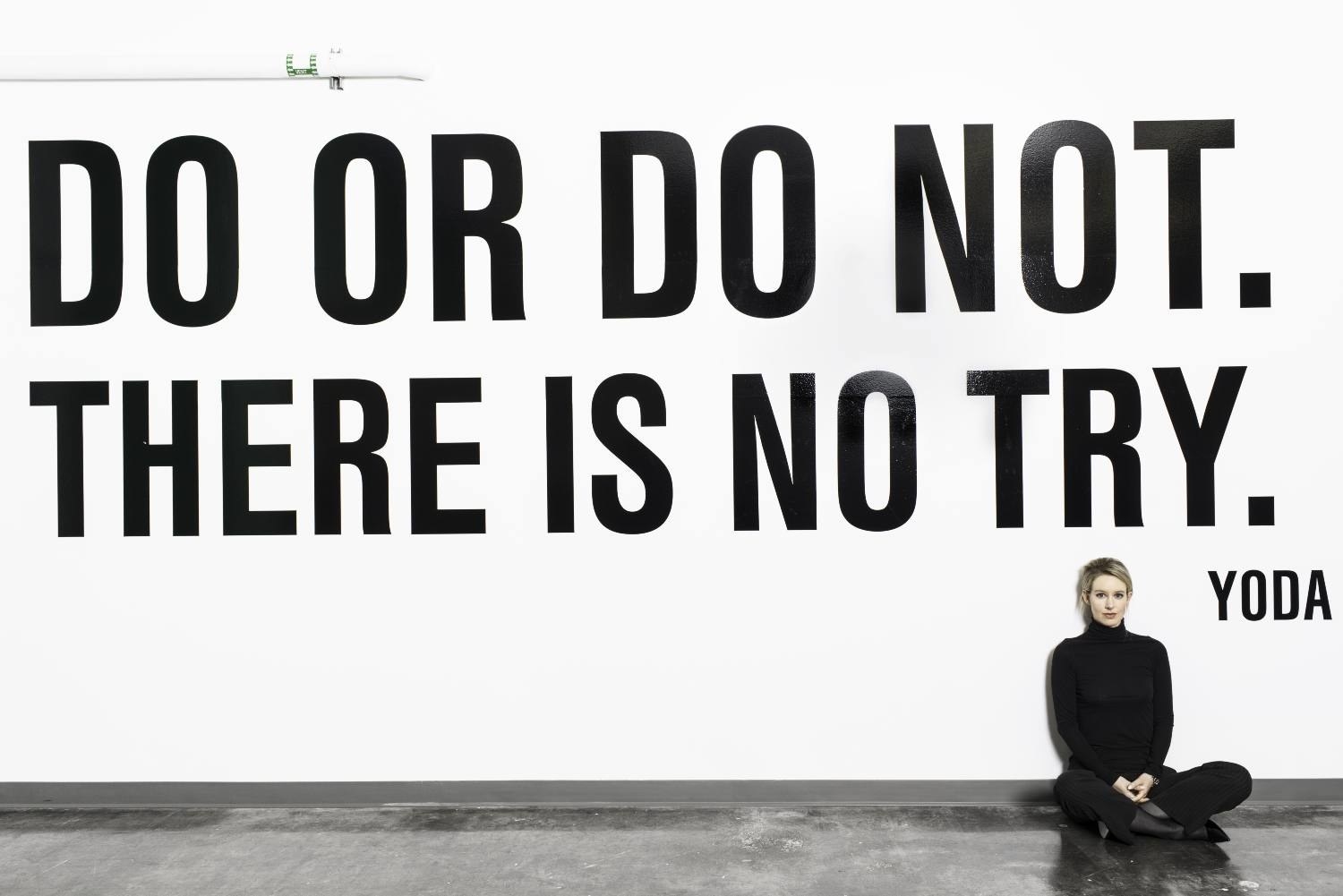

Everything about Holmes was artificial. The deep voice appears to have been an affectation, an attempt to summon up more of a sense of gravitas or authority. In Bad Blood, one employee notes how she briefly slipped into a higher register before correcting course: "In her excitement, she seemed to have momentarily forgotten to turn on the baritone." Her uniform of black turtlenecks was an homage to Holmes' hero, Steve Jobs, but also a way of emphasizing her all-consuming devotion to her work — she had no mental space to spare for something as frivolous as choosing outfits.

The green juices she drank were indicators that she didn't have interest in such fleshly pursuits as enjoying food. The security detail she traveled with was a physical underscoring of her own importance. The more you look (and there's so much to see), the more you can start to overthink about how much of the way she presented herself was a put-on — especially given that a lot of it seems to have been abandoned in the wake of the scandal. Was the hasty eye makeup intentional, meant to be read as a sign that she's not like other women who fritter away hours learning how to apply it? Or was she simply, like a lot of us, not that great with eyeliner?

Holmes collected signifiers of seriousness, some of which, like the voice, were clearly meant to combat gendered baggage around women in power by evoking associations of masculinity. Others were about positioning herself as a wunderkind, an otherworldly genius, a chosen one. "She has a sort of ethereal quality — she is like a member of a monastic order," Henry Kissinger, one of the many powerful men Holmes enlisted as an ally, says in The Inventor. In the same doc, the New Yorker's Ken Auletta recounts how she told him she was "married to Theranos" — though, of course, she was also in a romantic relationship with the company's president and chief operating officer Ramesh "Sunny" Balwani, a potential complicating factor that she opted not to disclose to her board of directors.

There was a lot that Holmes didn't share — like the fact that Theranos did not have a functioning product, or that the product they were trying to make might have been impossible (in The Inventor, one former employee says they were running up against the laws of physics). People who pushed back against the company's timeline or direction were fired and replaced. But it wasn't just the lying that enabled Theranos to continue for so long — many of her investors didn't want to know the details. They wanted to believe, to buy into what she was selling, which is that it's possible to save the world while getting rich at the same time, and that the best way to do that is to shove money into the hands of someone who makes huge claims and doesn't want to be asked many inconvenient questions.

It makes sense that the Elizabeth Holmes industrial complex has spawned so many projects and upcoming adaptations. If there's enough of an audience to support and debate two competing Fyre Fest films, and at least two Anna Delvey projects in development, then, really, the sky's the limit for all things Theranos. As a scandal, it's sprawling and involved — as a story, it has it all. It's also another installment in what now feels like an endless season of scamming; it confirms so much about the ludicrousness of how VC funding works; it speaks to the terrible need to deify tech executive as geniuses who'll change the world instead of people who are frequently full of shit and unprepared for the consequences of their companies' actions.

And it also has Elizabeth Holmes, a figure who feels too spellbindingly strange to be real (and, arguably, wasn't). She's a subject who seems tailor made for the modern take economy because that's how she positioned herself. She was a CEO who talked about herself as a savior. Late in The Inventor, footage is shown of her talking about how she was inspired by her uncle’s death from cancer that wasn't detected early enough to save him. It's a sad story, and she tells it well — somberly, and with conviction. And then the camera pulls back to display variations of it playing on adjacent screens, all from different speeches or media appearances — a personal tragedy transformed into promotional mythologizing, another compelling element of a corporate narrative.

The rise and fall of Theranos is ripe for infinite interpretations, and we're in a golden age of transmuting recent history into tougher truths on the page and on the screen. It's become a way for us to metabolize news stories, both decades and days old. In the wake of the college admissions scam that broke earlier this week, it was impressive and entirely unsurprising to see the swiftness with which a book deal about the scandal emerged. And as soon as the story broke, people on Twitter had started making predictions about what kinds of media adaptations would come from the story — Law & Order: SVU episodes, Lifetime movies, documentaries directed by, yes, Alex Gibney.

People actually argued over whether Ezra Edelman's masterful 2016 O.J.: Made in America was film or TV, a fight that was less about medium than ownership — everyone wanted to claim the ambitious 467-minute work for their own side, because it was that absorbing and thematically rich an exploration of race, class, gender, and American history. It was the kind of thing that you knew people would want to talk about, that would break through the wall of noise and unite people in conversation. It was the most lauded example of what's become a reflexive part of our news process — the true story being retold as a kind of documentary or scripted thinkpiece, a format that's really come into its own over the last few years.

A significant aspect of this involves reconsidering past scandals through a contemporary lens, highlighting how much was missed or unjustly skewed at the time in cases like those of Lorena Bobbitt, Anita Hill, and Monica Lewinsky. Leaving Neverland demanded we reckon with Michael Jackson, our relationship with celebrity, and how much was going on right in the open. There's a whole podcast, You're Wrong About…, cohosted by reporters Michael Hobbes and Sarah Marshall, that applies this approach to everything from the Satanic Panic to Amy Fisher. But as the double Fyre docs prove, these incidents don't have to be older for us to want to revisit them. News happens too quickly now, with social media allowing us to follow stories as they unfold in real time, as narratives emerge and shift in front of our eyes.

These reflections and adaptations have become a way of taking a step back and looking at what we missed — because it's too easy to feel like we're missing a lot. To consume these larger works is to both be reassured that in the time that's passed — whether it's decades or months — that we're making some kind of forward progress in our understanding while also being reminded that we're still harboring all sorts of blind spots and biases we're not aware of yet.

We're in the midst of a long-in-coming reconsideration of who gets to tell stories, both in terms of journalism and entertainment, and how that affects how those stories are told. We're also three years out from a scarring presidential election that proved how much mainstream media consensus could miss. These movies and miniseries come across as a reflection of our increasing awareness, if not necessarily increasingly wisdom, about the subjectivity of what gets presented as the objective truth.

Elizabeth Holmes was aware of how much we want a moral to a story, a message, and so she angled herself to offer up whichever one those around her wanted — the transparency of her posturing didn't matter. To her largely white, male investor base, she was a woman they could bring themselves to trust, because she performed a strategic genderlessness they found disarming. To her industry, she was a feminist icon, marketing her own triumph in the male-dominated world of tech, and ending an employee-focused film by saying, "I always say that next to every glass ceiling there's an iron lady." To the media, she was a figure dedicated to human rights, and the massive valuation she temporarily accrued was just a happy byproduct of her work.

If Holmes' story has a larger meaning, it's not just one about the tech industry, or about venture capital, or about media criticism. It's also a cautionary tale about our need to fit real-world figures and events into neater narratives — how the desire to boil them down to a larger meaning sometimes leads us to oversimplify, to ignore indications there might be more to the story than what fits into straightforward messaging.

The rise and fall of Theranos doesn't lend itself to a single interpretation, because it shouldn't — it's not a fable, it's a mess that offers up all sorts of astonishing details and instructive lessons. There's no single reading of Holmes' story, in part because it keeps going, right on to Holmes continuing to live happily in activewear with her dog, Balto, and her fiancé. She also apparently wants to write a book herself, or make a documentary — and how can anyone look away from that, or even blink? ●