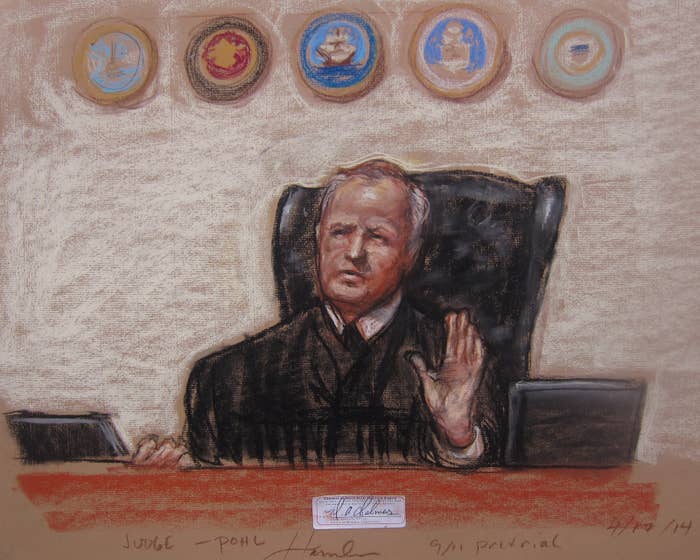

GUANTANAMO BAY NAVAL BASE, Cuba — "Commission in recess. Carry on," Army Judge James Pohl said, leaving the judge's seat here Friday. And with that, another session of the 9/11 hearings came to a close.

A courtroom full of the top military and civilian legal minds — most of whom parachuted into Cuba for the week-long hearings — had made marginal progress on around ten motions, and resolved two. The docket, which stands in the way of an actual trial, contains hundreds. They’ll return for a two week session in February to resume.

This is the usual pace for the military commissions process, which over the course of nearly 10 years has been derailed, stopped, and restarted again.

There is no sense of urgency here, no lingering push towards resolution in the courtroom. There are eye rolls. There are wisecracks. There are exasperated sighs, unnecessary delays and a grudging acceptance that no one is going anywhere anytime soon. When folks down here are asked about the prison’s prospective closing, the answer is simple: ‘That’s Washington’s problem, not ours’.

“If it takes long — the standard is not time,” chief government prosecutor Brig. Gen. Mark Martins told reporters the weekend before the most recent round of hearings. “The standard is the law and the rule of law. We’ll be here as long as it takes.”

Predictions on a deadline are considered fruitless here. Martins had predicted a handful of years ago that the long-awaited trial of the five alleged 9/11 plotters would start by January 2015 — asked about that date Saturday, he wouldn’t speculate. The prosecution team stated in court that it expected to be finished providing the defense team with the discovery documents the government thinks they're entitled to by September of next year.

That date, of course, is just the initial production of documents to defense lawyers, who can then appeal redactions or ask for other referenced documents.

"I see endless discovery litigation," said Walter Ruiz, a defense lawyer for Mustafa al-Hawsawi, one of the accused 9/11 plotters. "With at least that estimate and some of the discovery positions they're taking, I think 2020 would be optimistic [for a trial]."

Many of the liaisons assigned to escort the press this week would occasionally use the word “temporary” — it’s a temporary facility, a temporary set-up, a temporary Joint Task-Force. That word is almost always followed by an eye roll or a sharp laugh.

The court complex itself, a high-security facility wallpapered with “NO PHOTOGRAPHY” signs, seems to have grudgingly settled into the dry Cuban dirt. Tents have been outfitted with high-security screening centers for visitors and commissions personnel. Faded black sniper netting, once pulled taut around all aspects of the compound, droops lazily from the fences and over the corridor that holds detainees.

Every morning around 9am, Army Judge Col. James Pohl enters the courtroom, peers over his small dark glasses and calls the commissions to order. Every morning, he accounts for detainees, who have the option to waive their attendance in the courtroom. And like clockwork, every morning, 9/11 suspect Walid bin Attash leans up to his microphone and interrupts these initial housekeepings. In his high-pitched native Arabic, he requests to have reflected on the record his disapproval with his female lawyer, Cheryl Bormann. And every morning Army Judge Col. James Pohl slumps in his chair and tells him, with the slightest hint of exasperation, yes, Mr. bin Attash, it’s been added to the record.

The repetition would almost border the dry hilarity of a sitcom, if not for the sobering backdrop of death, destruction and torture.

This week of hearings saw an entire day lost to meetings, where lawyers and the judge discussed classified documents, and one full morning lost due to an unnecessary scheduling conflict — for reasons neither the Joint Task Force nor the International Committee of the Red Cross could explain, several of the defendants’ meetings with Red Cross personnel overlapped with trial proceedings.

The Obama administration has said, that even if Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and his four alleged 9/11 co-conspirators are acquitted in the military commissions process, it can legally keep the five of them indefinitely as enemy combatants. That ultimate endgame hangs on the proceedings like the heavy Cuban heat.

“If they're being held indefinitely, we have to make sure that at least their conditions of confinement fulfill international legal standards,” said Alka Pradhan, a lawyer for Ammar al-Baluchi, another of the alleged 9/11 conspirators. “We're already at 12 years and counting for my client, and the government spent several of those years torturing him. The very least we defense lawyers can do now is make sure that the United States treats these men humanely.”

Martins said Friday the group had made marked progress.

"We got some things done this week...pretty significant movements forward," he said.