In 2000, I became, somewhat by accident, the director of All Souls Unitarian Church’s Monday Night Hospitality program for the homeless, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. The former director had a medical emergency and had to leave her responsibilities immediately, and so the next week when I went in for my volunteer shift, I was asked if I would consider running the program, at least until someone else could be found. I would be acting director for three years.

On my first day, I went to Western Beef, a low-cost butcher shop and grocery store where the program did its shopping, the week’s dinner budget in an envelope of cash. And even though I had previously gone along with the director, as her assistant, I was nervous that first day on my own. The program fed 100 guests on a first-come, first-served basis — more, if more showed up. Some diners even took leftovers back to their shelters for those who couldn’t leave. This was a big responsibility. I planned the meal, bought the food under budget, and returned to the church, and I did the job for three years. Gradually the program expanded, especially after 9/11. I was proud of the work we did.

The calm with which I did this every week was not visible in the rest of my life. In the apartment I returned to after those volunteer shifts, my closet stacked full with boxes of files and receipts going back 15 years. Many were unpaid bills, missed payments, or collection notices. Letters from the IRS. A personal organizer I had hired a few years before had said, looking them over, “Oh, wow, you don’t need these,” then she laughed and told me to throw all the papers away. But I could not. When I eventually moved out in 2004, I moved with those boxes.

In some way I wasn’t quite aware of, I had imagined the problem was receipts. But I did not feel that pain when I shopped for the church’s program and put the receipts in an envelope before turning them over to the office. The more I kept a steady hand on the program, the more I was aware I was in the presence of a revelation about myself. The ordinary transactions contrasted with the pain I felt, almost supernatural, every time the money was mine.

The problem was there in every sale. Whenever the question came — “Would you like a receipt?” — I never wanted it. But I took it, knowing I should, and would put it quickly in my wallet, until the wallet bulged like a smuggler’s sack.

I had no system for the next steps. The receipts stayed in there, usually too long, sometimes fading to meaninglessness. Or I emptied the wallet into the pocket of a backpack, or I stuffed them into an envelope, always with the promise of getting to them later. Then I put them in the boxes. There they fluttered around like some awful confetti, saved for a celebration that never came.

I knew they represented, in part, money that could come back to me, but for me they mostly represented money lost. Pain is information, as I would say to my yoga students at the time, and my writing students also. Pain has a story to tell you. But you have to listen to it. As is often the case, I was teaching what I also needed to learn.

The pain these receipts represented was not particularly mysterious to me then. I had just never examined it. I hadn’t even felt I could. I simply thought everyone had these difficulties. But this was a lie I told myself, a way of accommodating the pain instead of facing it.

In a file I still have from 1989, there is a letter from my sister, when she was 15 and I was 22, asking me to send my tax form to my mother so she could give it to our accountant. This is in a folder with the tax return from that year, completed after I sent the form. I can see the earnings from the sandwich shop I worked at in Middletown, Connecticut, while a student at Wesleyan; earnings from my first months at A Different Light, the bookstore where I worked in San Francisco just after college graduation; and the taxes paid on the stock certificates I sold from my trust in order to pay off my tuition bill at Wesleyan.

I have tried to change my own relationship to money and pain, which are forever twinned in my mind.

Asking my younger sister to write and ask me to send the tax form was my mother’s way of communicating, off-kilter and indirect. To this day, she will ask one of us to communicate something to the other, though she could just as easily call directly. I have tried my whole life to change this in her, as I have tried to change my own relationship to money and pain, which are forever twinned in my mind. The anxiety about receipts was anxiety about money, but also much more than that.

Underneath that anxiety was the belief that there would be an accounting demanded of me, one that I would fail. After reading Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, where she describes keeping her late husband’s things as if he might return for them, I understood it a little better: I imagined someday having to tell my father about everything I had bought with the trust fund I received after his death. And having to explain how I’d failed him.

My father was so young when he died, 43 years old, that he hadn’t made a will, due in part to the faith the young have that a will can be written and notarized at some later date, because surely death is far away. As a result, the state of Maine divided my father’s estate four ways, among my mother, myself, my brother, and my sister — my mother receiving, by law, the majority. I was given a trust that would be vested to me when I reached the age of 18.

Just three years earlier, at the time of his death, three years after the car accident had rendered him paralyzed on the left side of his body, my mother had confessed to me she was repaying his medical bills, which totaled more than $1 million, on top of what was covered by their medical insurance. He’d had repeated surgeries over those three years, home care, physical therapy, and experimental treatments. My father’s family was wealthy enough to have helped us out, and for one year they had, but they’d held the cruelly contradictory belief that my mother should both be able to pay the bills and also not have to work — to stay home and take care of my father. I can only think they believed the money would magically appear out of my father’s business without anyone working there, a mistaken notion born of a mix of sexism and parochial privilege so extreme as to be laughable, if the price of it were not so steep.

This was unexpected and difficult. My mother did the only thing she could do. She put in 15-hour days, leaving me to cook for my siblings, to drive them to sports practices, to grocery shop, and even to shop for her clothes while she did this. She was soon able to pay off my father’s medical debts, and did.

And now we had arrived here. My 18th birthday.

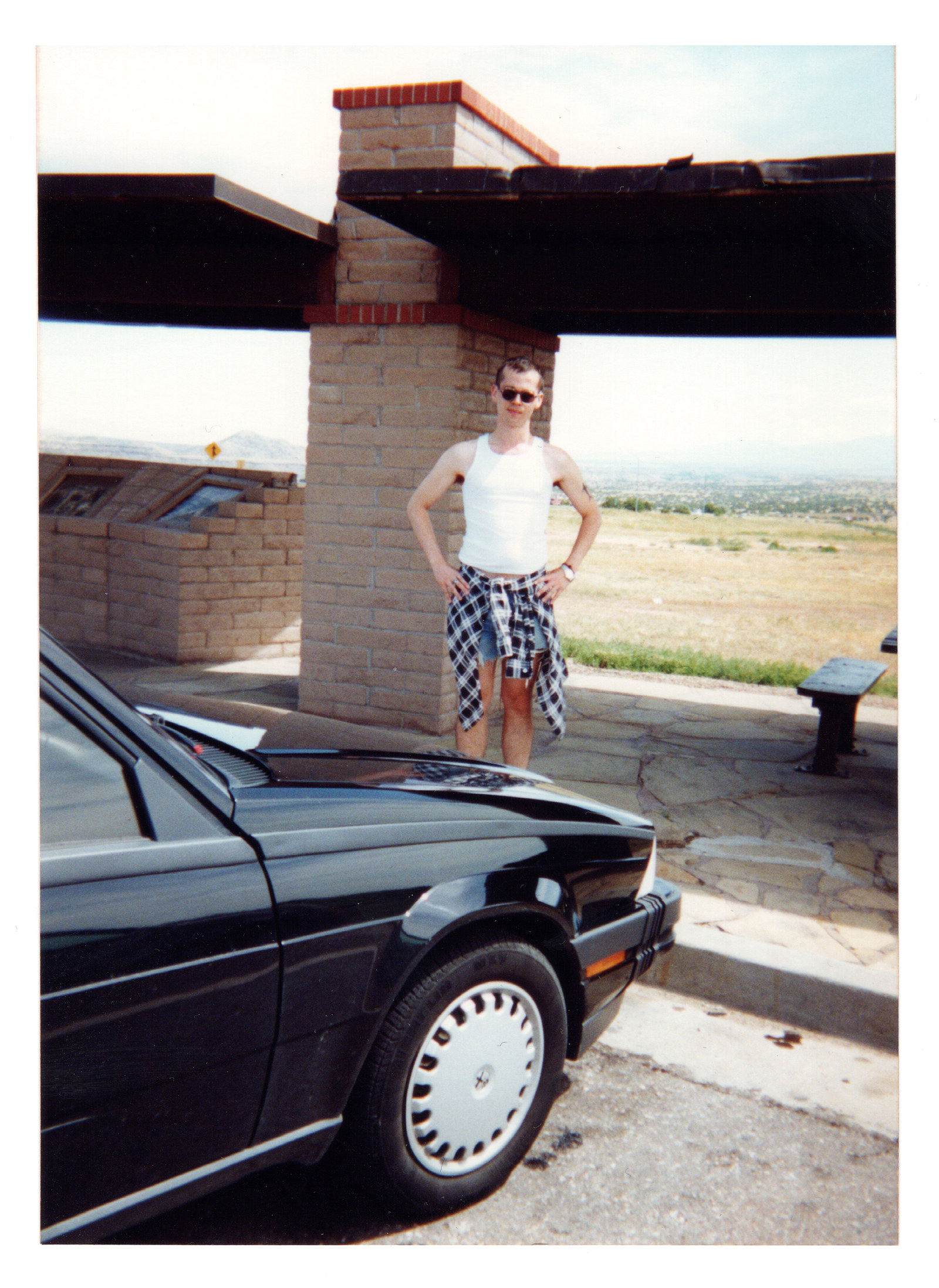

My mother told me the trust was, first and foremost, for my education and anything related to it, and I should spend it wisely. “Your education is the one thing you can buy that no one can take away from you,” she said portentously. Also: “I wouldn’t have given you control over that much money at age 18.” But the state had decided it, and she had to allow it. At the time, I rankled at the thought that I wasn't mature enough, but it was also true that for me to be presented with money enough for college after years of worry over mortgages and my father’s medical bills felt like an unearned luxury at best. As a result, the first thing I did with my money was part rebellion, part panegyric. My father had loved fast cars and expensive ones, both, and so I bought what I thought he’d want for me, a black Alfa Romeo — a Milano, the first year they were available in the United States — a sort of cubist Jetta with a sports car’s heart.

I drove off to college with my younger brother literally along for the ride — he wanted to see how fast it could go. He was the king of auto shop in high school, and had saved up the regular gifts of money given to him by our relatives over the years until he could buy the cars he rehabbed in auto shop, and then he sold them for more money. He has always had a gift for making more out of what he was given. He had taught me how to drive stick shift on his red 1974 Corvette 454, a car so beautiful the police would pull him over just so they could look at it.

My brother had been reading the Alfa Romeo manual, and after he looked at the speedometer, he said, “It says this car tops out at 130 mph,” and he gave me a little smirk.

I nodded. The highway ahead of us was oddly empty, and so I floored it. For a brief moment on the Massachusetts Turnpike, we flew, pushing the speed as far as I dared, a 130 mph salute to our father.

I drove the car for the nine years the trust lasted, except for when I lived in California. Then my mother, despite her objections to its purchase, drove the Alfa Romeo and enjoyed it, in what amounted to a truce on the subject. I used the remainder of the trust not just for my tuition costs, but to turn myself from a student into a writer. I paid for my college and left with no debts — an extraordinary gift. This gave me the freedom to intern at a magazine that published my first cover story, and to take a job at an LGBT bookstore that let me read during my shift, meet authors, and even help with the planning of the first LGBT writers conference, OutWrite. And while I went to graduate school on a fellowship with a tuition waiver, I had no health insurance, and so the trust money paid for my regular dental work and a trip to the hospital back in New York, where I lived before and after grad school. I know this freedom looks ordinary to many, but I also know all too well that it is rare when the children of Korean immigrants are given this kind of latitude from their family to pursue the arts, much less the financial support to do so, especially when they are openly queer.

I had believed I would feel lighter without money, free of the awful feeling of having it but not having my father.

Besides the car, what I thought of as my excesses at the time now seem more or less pragmatic to me. My clothes were usually secondhand, my books also, or purchased with an employee discount. I drove a used Yamaha 550 motorcycle when I lived in San Francisco, where there were four cars for every parking space. I traveled to Europe in the fall of 1990, to Berlin, London, and Edinburgh, to investigate whether I could live somewhere other than the United States. And while I ended up staying in the US after all, the trip was its own education. My greatest indulgences were probably during a long-distance relationship while in Iowa: phone calls that regularly cost as much as the plane tickets for said relationship, not otherwise affordable on a graduate student’s budget.

For those nine years, I felt both invulnerable and doomed, under the protection of a spell that I knew to be dwindling in power. The Alfa broke down finally while I was driving from Iowa to New York City. I left it where it stopped, in Poughkeepsie, on the street in front of a friend’s apartment. That summer, newly released from graduate school, with no job and no prospects, I had no money to repair it or move it. Eventually the car, covered in unpaid tickets, was impounded and sold by the state to cover the towing and storage costs. My money gone, I surrendered to life without either the trust’s protections or the car. I know it was all stupid, and I was ashamed, and felt powerless in the face of the problem and ashamed of that powerlessness. But I was also tired of being mistaken for someone who was rich when I felt I had less than nothing.

I had believed I would feel lighter without the money, free of the awful feeling of having it but not having my father. And yet spending the last of it was not just like failing my father — it was like losing him again.

We learn our first lessons about money as children, and these shape much of our ideas about it. We learn these lessons from our parents, but from others also. But I feel as if I have always been taught about money by everyone — every day of my life a lesson, whether I want it or not, in what money is and does.

The lessons my life had provided, up until my epiphany over my relationship to my receipts at All Souls’, were that money is conflict, strife, grief, blood. Money is necessary. Money divides families — even the promise of it, hinted at. And that nothing destroys a family like an inheritance.

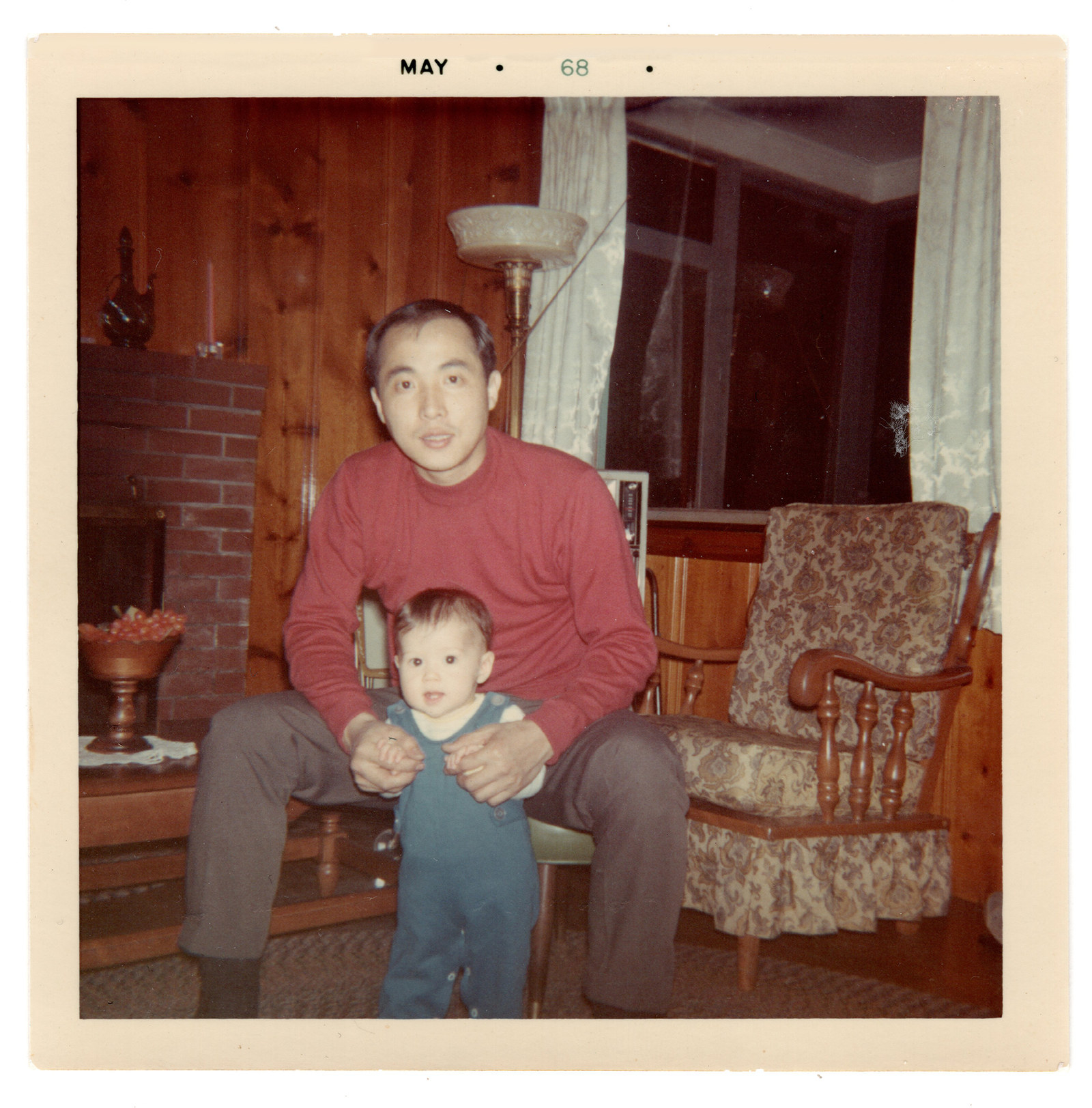

My mother likes to tell a story of me at age 2, in 1968. We were living in my grandparents’ home in Seoul, and three of my father’s siblings were still of school age — two uncles and an aunt. The three-story house was surrounded by a high wall, covered with nails, barbed wire, and broken glass, that I would later come to expect on houses like this all over the world — the homes of the rich, living amid great poverty. The house was near the Blue House in Seoul, the presidential residence; the Secret Garden, formerly a palace where the king kept his concubines, was visible from our third floor. For years it was one of the most privileged of neighborhoods, exempt from development.

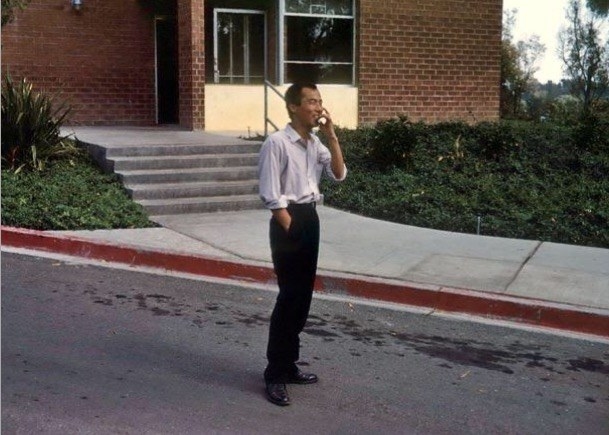

The reason we were living in Seoul is that my parents could not afford me on their own. When I was born, my father was a graduate student in oceanography at the University of Rhode Island. A favorite photo I have of him from that time shows him posing with his URI classmates, holding a whale rib. My mother taught home economics at the local public school, and since women were not allowed to teach while pregnant, married or not, she was dismissed when she started to show, and the economic crisis that I was began. My birth was unplanned; my parents were not financially ready to start a family. In the first photos of my father holding me in his arms, he looks tired and dazed, and the expression on his face is one of amazement, love, and frustration. He seems ready to agree to his father’s offer of a job back in Korea, which came soon enough.

The lessons my life had provided, up until the epiphany over my relationship to my receipts at All Souls', were that money is conflict, strife, grief, blood.

Every morning, my father’s school-age siblings lined up to ask for their lunch money, and on this particular day, after the youngest had taken her turn, I went and asked for some as well. My grandfather was so charmed — he was worried I would never speak Korean — that he came downstairs, laughing, and gave me some money too. I was then allowed to spend it across the street at the small market, to get a treat.

I did the same the next day, and the next. It made him laugh, and soon he gave me money daily for treats.

My father’s siblings still resent me, I think, because of it. I became just another sibling to compete with for attention, approval, and money.

I was born slightly premature, and so at age 2, because I was underweight, I was allowed to use my daily allowance to buy a chocolate bar. This is the context for the next story my mother likes to tell about me from this time: She decided one day to punish me for something, and told me I could not go to the snack stand across the street. Later, she found me eating my chocolate bar. Confounded, even alarmed, she asked me how I had done this.

The maid explained that I had sent her with the money I’d been given.

My mother tells this story as an example of my shrewdness in the face of an obstacle, also my devilishness. And I do like to think the story is about my improvisational mind. But it also shows that even at a young age, I understood how power worked. I was adapting to my sense of the class I belonged to, as all children do. That this class would change, that I would become a class traitor — as all writers are, no matter their social class — was all ahead of me. Perhaps this was preparation for that change: reading context clues for signs of how to get around the stated rules — how to find the real rules, in other words, that no one ever tells you but that everyone obeys.

However it happened, my relationship to money began before I can remember it, and it seems it started that way.

My parents did not give me lessons in money so much as they enacted them. My father spoke of money only rarely. Years later, after we had left Seoul and settled in Maine, and he had taken his degrees in oceanography and engineering and started his own fisheries business, he explained his absences from church on Sundays by saying, “My church is the bank, and I’m there five days a week.” He dressed for work in well-tailored suits from J.Press, wore handmade shoes from England, and was uninterested in cutting a low profile. He was the first nonwhite member of his golf club and the Kiwanis and Rotary clubs, and he never looked less than sharp. That this sort of dapper dressing was something he had to do — that his appearance, as an immigrant, required him to be tailored, impressive, to project wealth or at least comfort, just to be treated with respect — would not be visible to me until much later, but he did enjoy it. I remember he said, “I’m treated better when I fly if I wear a suit jacket,” and each time I put one on to fly — and he’s right, I am treated better — I feel closer to him.

Both of my parents had worked hard for what they had — my father, with his older brother, had scavenged for food from abandoned army supply trucks in Seoul during the Korean War. My mother had cleaned hotel rooms during the summer for the money she used to buy the car she drove away from Maine. My father believed money was for spending, and my mother believed it should never be spent. Her clothes were handmade also — for much of her life, she made them herself. She was as stylish as my father, but by her own hand.

The only time I recall hearing my parents speak of money together was the day my father came home with an antique 18th-century Portuguese cannon, “the only one of its kind with a firing piece,” I remember my father explaining. My mother was as angry as she’s ever been. He had spent their savings on it: $750 at the time. The seller was a Marine who had, with his buddies, each taken one of these cannons back to the US from Korea at the end of the war. Or so he said. Part of my mother’s anger then was that there was no certification of its authenticity, but also, as she said that day, “What are we going to do with it? Declare war on the Mullinses?” It was a strange, brute artifact, out of place, and after the purchase, it stayed behind our blue corduroy couch alongside many of our father’s rifles, by the entrance to our suburban two-story house. As if it were hidden there in case we ever really did need it.

After my father’s death, we considered having the cannon appraised, even selling it. We also thought of selling his Mercedes. We did neither. The cannon sat behind our living room couch for years and is now my brother’s. We couldn’t part with it. My brother did recently admit to having the cannon appraised by Christie’s; it is now worth $28,000. Thirty-seven times its original price, thirty-seven years later, the lesson of the cannon is at last visible: My father was right.

The first allowance I remember receiving was given to me to soothe the pain of the allergy shots I required, starting around age 7, as a child in Maine.. There was the sharp flash of the needle’s injection, and then, at the corner store near the doctor’s office, my father would hand me a quarter, which I could use to buy comic books.

The cycle was pain, then money, then power over pain. A feeling like victory — if not over the pain, at least over powerlessness. And one of my earliest experiences of fatherly love.

Pain, money, power over pain. My mistake being that money is not power over pain. Facing pain is.

I was searching for new narratives with which to remake my relationship to money.

In the first years after the end of the trust, I dreamed of a payday as big as the trust had been, imagining it could save me, because it was all I could imagine. I see now it never could. It was only a dream that the sacrifice of the trust could return to me as a payday the size of the trust, a simple exchange that would clearly mean it had all been worth it, in the primitive religion around money and self-worth that I had made for myself. But this longing for a payday was really just a mix of two stories in my head, turning the money from the father into something that both conquers the pain and also stands in for it.

I was searching for new narratives with which to remake my relationship to money. I had several identities, whether I was aware of them directly or not, some due to my own parents’ searches for the same: as the child of a scientist father and schoolteacher mother; as the child of entrepreneurs, once both parents moved on in their careers; and, as a friend of mine likes to say, as a lost prince, far from his kingdom. My identity as a writer was the newest of these.

I wanted to belong to myself, much as my father had — and the stories I had of him, as someone who had worked multiple jobs in order not to rely on his father, inspired me also — and so, with my trust fund gone, I not only waited tables, but took any work I could get. I had been raised with the idea of writing as an inherently unprofitable enterprise from which one derived token sums of money while being supported by other means, and I had to teach myself to fight this, too. My mother was fond of asking me to get an MBA and write on the side. My grandfather, in our last visit before his death, said to me, “You are a poet, which means you will be poor, but very happy,” and then he laughed uproariously.

I laughed too.

These allowances, this trust, had taught me only one thing: Money belonged to other people, not to me. I was trying to undo the spell all of this had cast on me, beginning with the lunch money my grandfather used to give me back before I could remember, which became the $100 bill he would give me whenever he visited from Korea. I was learning to walk in a new world, in new gravity, and by the year 2000, when I was made the acting director of the All Souls Monday Night Hospitality program, I had been living in that world for six years. I had joined the church with a boyfriend, and had stayed after we broke up. “We don’t expect to see you on Sundays if you’re here on Monday nights,” the reverend had said to me when I apologized once for missing the services — the church, on the Upper East Side, was a long way from where I lived in Brooklyn. That idea of acts of charity as service, as a way of offering something to God as well as to others — the Monday service counting as much as or more than the Sunday one — made me feel at home.

I did not cure myself entirely. I am still curing myself. I am almost through those boxes of files. I let go of the fantasy of a massive payday and taught myself instead to get by with the shepherding of sums. I came up with rules I still live by: Always keep your rent low, no matter the city you live in; write for money more than for love, but don’t forget to write for love; always ask for more money on principle; decide how much money you must make per month and then make more than that as a minimum; revise the sum upward year by year, to match inflation. Do your taxes. Write off everything you can.

To the extent I have survived myself thus far, it began there — when I realized I treated money emotionally and decided to treat myself as I would anyone else I was taking care of. Ordinary thrift and self-forgiveness were the payday only I could provide, no matter my professional or financial circumstances, and this realization was the gift of that time, as close to a Unitarian grace as I think I’ll ever get.

These small things I did saved me when nothing else could. ●

Alexander Chee is the author of the novels Edinburgh and The Queen of the Night, and an associate professor of English and Creative Writing at Dartmouth College. This piece has been adapted from an essay in Chee's forthcoming collection, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel.

BuzzFeed News is partnering with Death, Sex & Money to share stories about class, money, and the ways they impact our lives and relationships. Follow along here.