It’s been 25 years since Whitney Houston broke sales records with the soundtrack of the blockbuster melodrama The Bodyguard, best remembered for Houston’s cover of the iconic Dolly Parton breakup song “I Will Always Love You.” In 1992, the song shot to No. 1 for 14 weeks and helped the movie’s original soundtrack album become the best-selling in US history, with sales now totaling 17 million. The unusual a capella opening of the song — still a rarity for a radio single — explicitly foregrounded the intimacy of “The Voice,” and became indelibly associated with Houston and her image.

The heartbreak ballad remains the best-selling single by a woman in music history, and is still culturally resonant as the object of endless drag homages, talent show displays, and, this year, as a musical punchline in the movie The Hitman’s Bodyguard. The Bodyguard’s soundtrack was recently turned into a successful musical, which doubles as a celebration of Houston’s career. And Christina Aguilera’s emotional tribute to the film's music at the American Music Awards this past weekend was yet another reminder of the way the soundtrack is deeply interwoven into popular culture.

At some point in their career, almost every pop star attempts to transition into acting, and the results range from the outrageously bad (Mariah’s Glitter, Madonna’s Body of Evidence) to the middling (Beyoncé in Dreamgirls, Michael Jackson in The Wiz). It’s rare for a pop star to appear in a movie that actually expands their music stardom; Prince’s Purple Rain is one of the few successful examples, and that project is seen as the epitome of his defiant “genre-hopping, gender-fluid” sensibility. The Bodyguard, judged purely on its cinematic merits, doesn’t necessarily hold up as well. But it endures as a cultural touchstone, and that’s primarily thanks to the film’s now-iconic songs, and to the performer who sang them.

“It was number one, the biggest soundtrack for movies of all time,” producer Narada Michael Walden, who worked with Houston on the Bodyguard album as well as some of her other biggest hits, said in a phone interview in November. “No one had seen anything like it. The only thing that could compare with that kind of sales was Thriller, Michael Jackson.” But for all the memorials and the focus on “I Will Always Love You,” Houston herself is rarely credited with shaping the project’s cross-platform success.

Since Houston’s death, the endlessly revisited tabloid drama around her life has sometimes threatened to overshadow her musical legacy. If she was once seen as a victim of Bobby Brown, more recently she’s been depicted as whitewashed and kept in the closet by record producer Clive Davis and her mother, Cissy Houston. Her performance of black femininity through so-called universal love songs and scripts often produced by white men seems to confirm that, as a recent documentary suggested, her persona was made palatable to white audiences at the expense of her true identity.

And it’s possible to slot The Bodyguard — with its interracial romance and huge “crossover” appeal — into that ultimately tragic plotline. Her role in The Bodyguard as Rachel Marron, a huge pop star who falls in love with Kevin Costner’s character and is later literally rescued by him, arguably played into the ultimate “white savior” script. Echoing the way Davis has long been given credit for shaping Houston’s music and public image, the media narrative around the movie suggested that Costner was the behind-the-scenes maker of her acting career. His film Dances with Wolves had won seven Academy Awards when he stalled production of the Bodyguard project for two years to wait for Houston, his chosen star, for the project.

But Houston wasn’t waiting to be “discovered”; she was already a massive pop phenomenon by the time of The Bodyguard; she’d won two Grammys, had nine No. 1 singles, and was the first female performer to have an album debut at No. 1 on the Billboard Charts. In 1986, People magazine readers voted Houston America’s Top Star. She had her pick of prestige Hollywood power players, including Robert DeNiro and Spike Lee, who wanted to work with her. And it was not just Houston lending her voice to big ballads, but her sensibility and creative decision-making that ultimately helped make the film’s music — and thus the film itself — the success it became.

In interviews with the songwriters and producers who worked on the project with her, it becomes clear that Houston, both in the way songs were custom-built for her voice and persona, and in the way she made those songs her own, played a central role in shaping The Bodyguard’s sound.

“She was truly in control,” producer BeBe Winans said. “She grew into that confidence. She was playing catch-up for the first and second album, and then she caught up to how to become immune to what people would do or say,” he said. “For the Bodyguard soundtrack, she was who she was.”

Houston herself described the Bodyguard soundtrack as the moment when she came into her own. “From ‘How Will I Know’ to ‘Love Will Save the Day,’ that girl’s gone,” she told Out magazine in 2000. “From ‘I Will Always Love You’ on, that’s a woman.” Though the soundtrack is technically credited to Houston and “various artists” (it also included songs by Lisa Stansfield and Kenny G), it is most remembered as a Whitney album, and Billboard counts it as such. And thanks to her work on the soundtrack as executive producer, the then-29-year-old became one of the few black artists — let alone black women — to be honored with a Grammy for Album of the Year.

The cultural celebration of Houston as “The Voice” implies that she simply recorded vocals as needed. And certainly, part of Houston being in control meant letting the producers that she trusted do their work. As Winans pointed out, by the time of the soundtrack, she had become “more understanding of a song, more so than just singing the song, and was part of those decisions of what songs she was going to sing. Now if she trusted you, as she did other musicians and songwriters, she would allow you to do what you do, and again take that song and make it her own.”

“I Will Always Love You” is a perfect example of Houston’s influence behind the scenes. The song plays a pivotal role in the script. It is first heard on a jukebox (in a soft-rock version sung by John Doe) while Costner’s bodyguard character Frank Farmer dances with Houston’s Rachel Marron in his own milieu, a working-class bar. The song’s reappearance at the end of the movie — with Houston’s full-throated vocals — is meant to be Rachel’s parting gift to Frank, re-presenting the song to him through her voice and aesthetic.

Costner originally wanted the ’60s Motown soul hit “What Becomes of the Brokenhearted” to play that pivotal role. But, as mega-producer David Foster said, in a November interview, Houston didn’t think that song worked for her. “I played it for her in her trailer,” he said, “and she was really nice, but she was like, ‘Ugh, this doesn’t really fit me.’” When the song was slowed down as Costner suggested, it didn’t have the “meat” — in Foster’s words — for her vocals in a final act song. “She said, very politely, ‘Would you try and make one more demo? And make it a little more ... interesting?’”

As he worked on a second demo, “What Becomes of the Brokenhearted” was released on another movie soundtrack. The music supervisor Maureen Crowe suggested Linda Ronstadt’s cover of Dolly Parton’s “I Will Always Love You” as a replacement. “I immediately knew what do with it and how to make it great for Whitney,” Foster recalled. He imagined “the big moment at the end; the stop, the strings, it all came to me, and I ran and did the demo, and of course, she loved it,” he said. ”It had ‘Whitney’ all over it.”

As Foster’s comment suggests, and as he has stated before, Houston’s improvisation and vocal trademarks — “Whitney all over it” — influenced the production. When the song was recorded during the movie’s filming at the Fontainebleau hotel in Miami, Houston “insisted on singing the song live in the film, and she wanted her band to be playing along with her,” saxophonist Kirk Whalum recalled. Her band director, Rickey Minor, recently mentioned in an interview that filmmakers had a backing track ready for her to sing over, “but she asked to have her live band play so she could hold notes out to her liking and perform the ballad in a more organic way.”

But while Whitney could always take big, dramatic ballads and make them her own through her voice — she did the same with “I Have Nothing” and “Run to You” — she had a more direct creative hand with the movie’s other major featured song, “Queen of the Night.” It plays a big role in the movie’s plot, causing a riot during a nightclub performance, which meant it couldn’t be a laid-back ballad or smooth mid-tempo song.

“Whitney brought in L.A. Reid and Babyface, who were friends with her and she’d had success with, to write the song,” Crowe said. Reid and Kenneth “Babyface” Edmonds were busy creating the Boomerang soundtrack, and it was taking them a long time to come up with the song, so “Whitney went in and finished the song with them” and earned her first writing credit, Crowe recalled. “She felt like they had limited time and they wanted to make sure they were writing something she was comfortable with,” she said. “She had been working on her character, so they wanted her to come in, ‘we’ll hammer this out together,’ with the idea of getting the rhythm right, the attitude right.”

Through Houston’s collaboration, “Queen of the Night” became a high-energy, drum-centric, pop-rock showpiece, with Tina Turner–esque growling, that showed a different side of her persona. The lyrics were her most in-your-face yet, and her outfit in the movie — a futuristic black leather and silver ensemble — became one of her most iconic looks. Though it’s unclear what lyrics Houston wrote (Babyface didn’t return a request for comment), the line “‘Cause I ain’t nobody’s angel / What can I say / I’m just that way” mirrors sentiments she shared with Rolling Stone at the time, complaining about her ball-gowned image: “I am nobody's angel,” Houston told the interviewer. “I can get down and dirty. I can get raunchy.”

The other two songs Houston chose for the soundtrack weren’t specified in the film’s script, and were the most personally meaningful to her: a pop version of the gospel standard “Jesus Loves Me,” and a cover of Chaka Khan’s funky 1978 hit “I’m Every Woman.” The script called for a gospel song for Rachel Marron to sing with her sister, out in the woods, as she escapes threats to her life in the city. Houston wanted the song “Jesus Loves Me,” but the hymn only has one verse — and while that worked for the brief scene in the movie, it wouldn’t work as an actual song on the soundtrack.

So she turned to gospel producer and longtime friend BeBe Winans to create a new version of the song, with a second verse, that could fit alongside the rest of the soundtrack. “She was always one to encourage me, and she’s like, ‘Write another one,’” Winans said, chuckling at the memory. “‘Really? This most incredible, simple, and profound song in the inspirational world, you just want me to meddle with?” he remembered replying. “So I did, and became part of the writing of this incredible song.” But, he said, convincing the film and record company to include the version of the track Houston had in mind wasn’t a given. “It was a fight to get what it deserved, and she made sure it did. It was something very personal, the song was very personal to her, and she fought for it.” (It would become the B-side to the single of “I Will Always Love You.”)

Unlike “Jesus Loves Me,” “I’m Every Woman” wasn’t even featured in the film, but the anthemic statement of black womanhood spoke to Houston at that point in her life. “She was pregnant, here she was in her first movie, she was getting married,” Crowe said of Houston’s frame of mind at the time. “That was really Whitney’s idea to do that song. It reflected where she was at the time.”

“Whitney herself called me, on the telephone, and asked me would I make a song for her,” said Walden, who produced the cover of the song for the album. “And this was really unusual, because normally everything I did to that point was through Clive Davis. This was the first time she was calling me herself, and she wanted me to make it a hit.”

In her version of the song, which is transformed from the disco of Chaka Khan’s original into ’90s house dance, Houston included an inspired outburst as an homage to her funk-soul predecessor. “Whitney appeared, seven months pregnant, really big, and she was so excited to sing this song because it was a real favorite of hers, and this was a personal thing between her and I,” Walden said. “She sang her ass off, and she wanted to be correct in all her harmonies. Chaka Khan is very deep in her harmonies, and here is Whitney laying every one of her harmonies,” Walden remembered, “and Whitney was so inspired that she just went ‘Chaka Khan!’” In the video for the song, a pregnant Whitney surrounds herself with other black women and girls (which she also did in the concerts for the soundtrack) and brings out the song’s history of black women creators and performers by including the original Motown writer Valerie Simpson, Chaka Khan, her mother Cissy Houston, and even the members of TLC.

In many ways, those two songs laid the groundwork for Houston’s future projects; the gospel of “Jesus Loves Me” preceded her full-length pop gospel album and movie The Preacher’s Wife, and her collaboration with and foregrounding of other black women’s voices hints at her role in reshaping the Waiting to Exhale soundtrack. (She refused Babyface’s idea that that soundtrack be a collection of her songs, because she wanted to feature the multiplicity of black women’s voices; it ultimately included songs by artists ranging from Mary J. Blige to Patti LaBelle.)

Houston’s work on songs like “I’m Every Woman,” which became the Bodyguard soundtrack’s second top-5 hit, and “Jesus Loves Me” — which in some ways has been overlooked in favor of the splashier singles and big-voiced ballads — is a reminder of the complexities of her musical persona. While the public loves “I Will Always Love You,” and she did too, these songs were the work of an artist who knew how to play into and depart from public expectations.

“What happens with success is, especially with record companies, they want that success to continue,” Winans said. “So what do we want? We want you to do that same album you did before. ‘Don’t deviate, we want to duplicate this.’” But by the time of the Bodyguard soundtrack, he thought, Houston had reached a point where her attitude was, “Oh, I don’t care about the success of the album to the degree where it’s going to continue to cage me, or what I feel, or what I want to do. It may not sell nothing; okay, that’s fine too. There’s other parts to me.”

This was prompted, in part, by the developments of her personal life. As Narada Michael Walden recalled, “It was a lot demanded upon her, but during the making of Bodyguard she was extremely happy because she was pregnant and it just made her ooze with everything that we love about her, but times three, times four.” And that personal and professional confidence helped create her best-selling album.

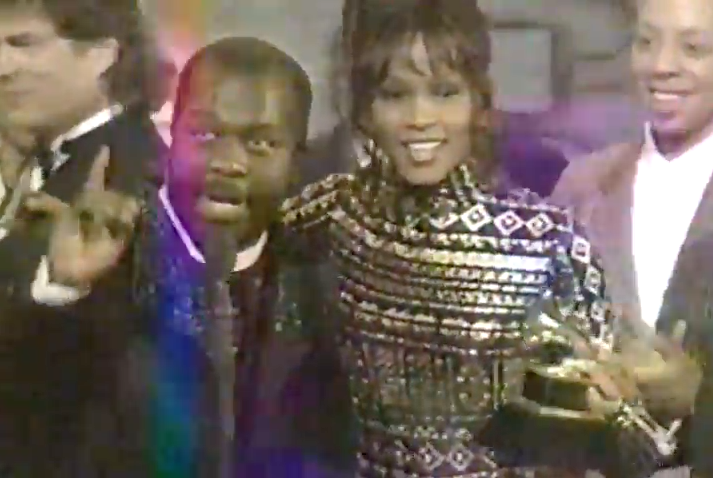

When The Bodyguard's soundtrack was named Album of the Year at the 1994 Grammy Awards, Houston went up to the stage with the rest of the producers. She was quickly surrounded by David Foster, Narada Michael Walden, Robert Clivilles, Babyface Edmonds, and BeBe Winans. Throughout the night — as “I Will Always Love You” went on to win Record of the Year and Best Pop Female Vocal — the producers all thanked different people or deities, but they also all thanked the one person who had brought their wide-ranging sensibilities (bombastic pop melodrama, rock, R&B, gospel) together in one album: Whitney Houston.

The Bodyguard-era image of Whitney was overtaken, in her final years, by decontextualized outbursts from Bobby Brown’s reality show and “crack is wack” and “show me the receipts!” memes, hinting at the way the pop zeitgeist was beginning to reinterpret her image. Particularly in the post-Lemonade era, Houston’s adherence to an earlier, less outspokenly political form of pop universality has come to seem old-fashioned.

Perhaps that is why, despite the global ubiquity of her music and her complete pop domination, the public rarely credits Houston as a visionary, multimedia trailblazer, in the way that it categorized her contemporary commercial peers like Madonna, Michael Jackson, and Prince. But her role in choosing and making these songs for The Bodyguard is a reminder that she never simply adhered or lent her voice to ready-made scripts. She was a keen collaborator who knew how to make room for her musical sensibility and image in a white- and male-dominated industry. She was “The Voice,” but she was also so much more. ●