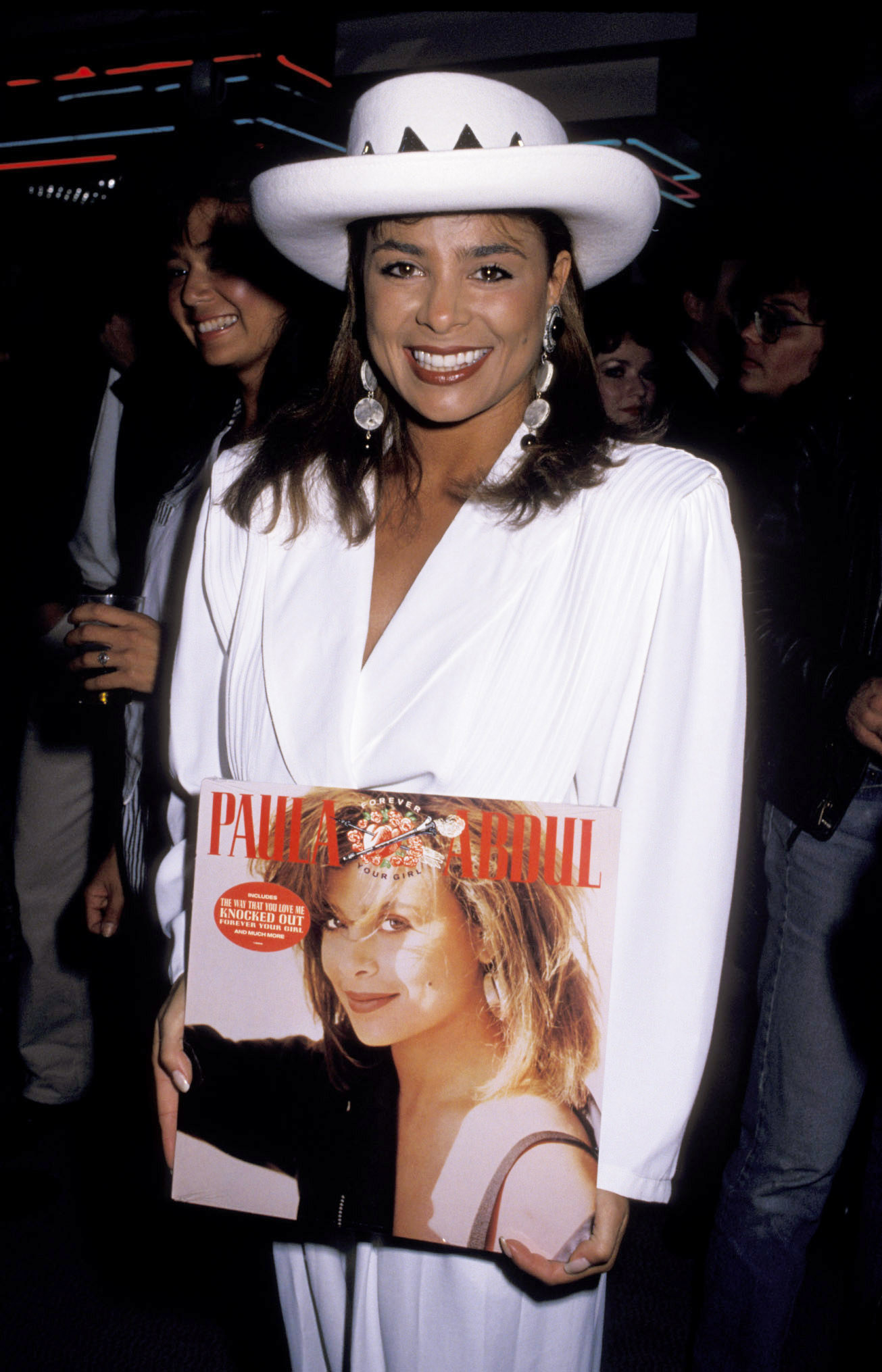

Paula Abdul exists in today’s culture largely through her reality television stints: as the zany (and nice) judge on American Idol, and the tearful, memeworthy diva — mocked by Kathy Griffin — from her 2007 reality show Hey Paula. But long before that, she was the original “pop princess” — an avant-la-lettre Britney Spears — initially launched to stardom 30 years ago today, with the release of her 1988 debut album, Forever Your Girl.

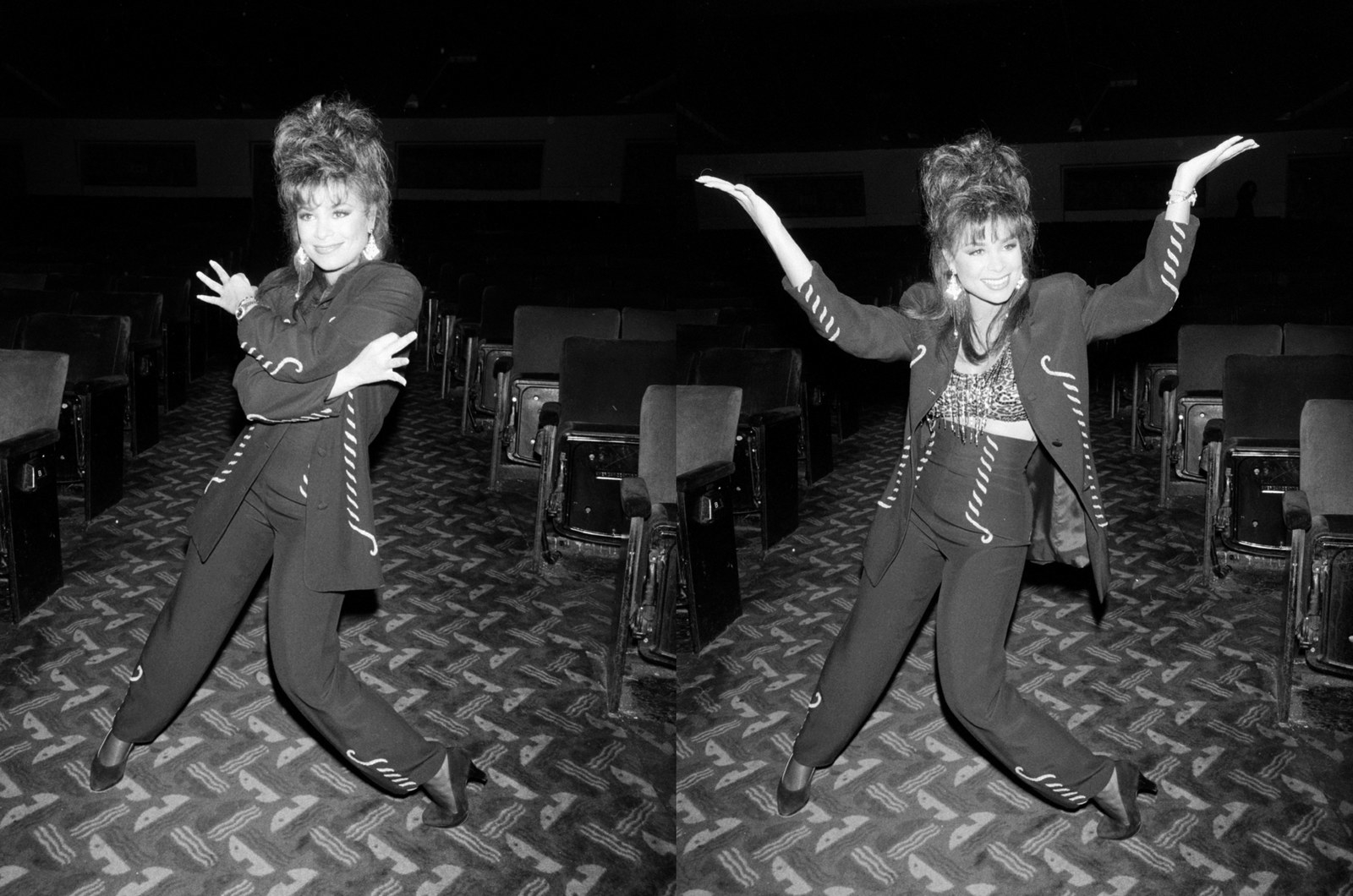

Abdul’s crisp dance moves and coy, girlish attitude eventually helped propel the album to record-setting success, garnering the first four of her six No. 1 singles. Those hits demonstrate the range of her pop persona, from the sweetheart appeal of the title track to the iconic David Fincher-directed video for “Straight Up” to the deep cheese of a duet with the rapping animated “skat cat” in “Opposites Attract,” which Abdul recently reenacted with connoisseur of corniness James Corden. (He plays the cat.)

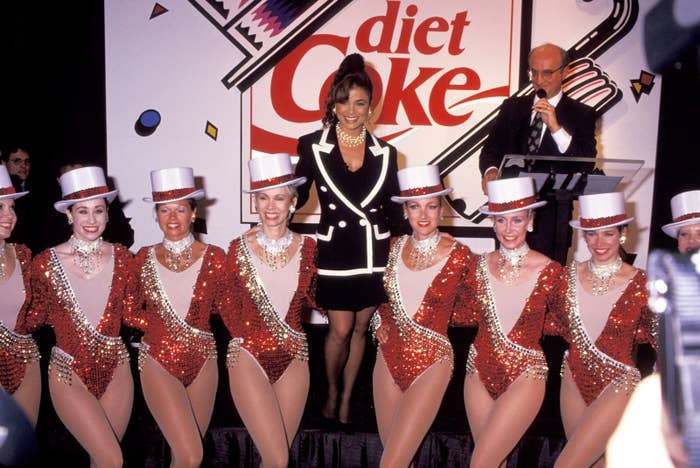

They turned Abdul into a Diet Coke-endorsing superstar, and throughout the late ’80s and early ’90s her commercial success rivaled Madonna and Janet Jackson. “She was like Miss America in people’s hearts, when she was at the height of her success,” former Virgin Records A&R vice president Gemma Corfield, who worked closely with Abdul her entire career, tells BuzzFeed News. But while there are entire cultural studies syllabi devoted to Madonna, and reclaiming Janet Jackson’s legacy has become its own genre of criticism, Abdul’s brief pop reign has largely been lost to history.

In fact, Forever Your Girl became a slow-burning success only after it had almost been written off as an irredeemable flop. The story behind the making and release of the big hits off the album, written by producers Oliver Leiber and Elliot Wolff, reveals the alchemy that resulted in its particular sound, in many ways a reflection of Abdul’s quirky humor and perspective. And it serves as a reminder that record companies and producers can’t manufacture big stars from the top down.

“It was a confluence of innocence and being unafraid that brought it all together,” says Corfield. “Once you have success, then you’re trying to always beat the success. But when you haven’t had any, you don’t know any better.” Leiber describes the process of selecting “Opposites Attract,” one of the album’s No. 1’s, a little more bluntly: “It’s not like it was Clive Davis with an amazing ear that said, ‘That’s a hit for Whitney,’” he says. “It was Gemma saying, ‘Do you have a third song?’ and me making up a half-assed chorus over the phone.”

Pop stars tend to be best remembered for being either transgressive, era-defining stars or nostalgic one-hit wonders. Abdul landed somewhere between those two extremes, maybe in part because, as she sang in her last original song (which she performed on American Idol in 2009), she was “just here for the music.” Unlike Jackson or Madonna, she was never interested in generating controversy or using her songs as a form of autobiography, and female pop stars historically haven’t been taken seriously when they just want to sing and dance.

In a post-poptimism era, most people accept that an artist who isn’t a songwriter, or who doesn’t have a powerful voice, can still matter culturally; the New Yorker covers Britney Spears. But that wasn’t necessarily the case in the early ’90s. Abdul did win one Grammy for a music video and two Emmys for her still-influential choreography, but ultimately, as Rolling Stone writer David Wild put it around the time of her rise, she was seen as proof that “an uncanny grasp of style and image can compensate for a lack of innate musical talent.” Taken all together, Abdul’s discography is often corny in a so-bad-it’s-good way, but cheesy pop has its own rules and inspirations. And for a brief moment, Abdul choreographed them into something unforgettable.

Abdul famously transitioned into the music industry when her work choreographing the Laker Girls led to her discovery by the Jacksons. After helping craft Janet Jackson’s moves for the “Nasty” and “Control” music videos, she was signed to the then-new label Virgin Records by Jeff Ayeroff, who had worked in marketing at A&M Records with Janet. “She said, ‘I can sing, you know. I want to do an album,’” Ayeroff recalled later. “Here's someone with a personality and she's gorgeous, and she can dance. If she can sing, she could be a star.” But the story of how Abdul found her bearings as a professional singer, and learned to work with producers, is not quite so straightforward.

One of the main criticisms leveled against Abdul after her album’s release was about her voice. LA Times journalist Dennis Hunt, profiling Abdul in 1989, called her voice “just passable,” and Abdul told him, “With my singing, there's room for improvement." But, as Corfield points out, “She didn’t play an instrument or was a good singer in the traditional sense of the word, but she had an unusual and unique tone to her voice, intrinsic value to her voice, that was very catchy.”

That didn’t immediately emerge on the first song she recorded for Forever Your Girl, “Knocked Out,” produced by Babyface and L.A. Reid. At the time, Reid and Babyface were on their way to peak popularity, and they “didn’t want to spend a long time in the studio fiddling about with her there,” says Corfield. “I don’t think they were that empathetic.” In his memoir, Reid recalls — in diplomatically brief terms — that it took “a long time to record her vocal.”

Leiber remembers how affected Abdul was by that first recording experience. “I don’t know if they gave her an hour or 15 minutes, but they kicked her out,” he tells BuzzFeed News. “They said, ‘Thank you, you know what, we’re gonna finish this record without you,’ which freaked Paula out,” he says. “She was sort of traumatized from that experience.”

The album’s sound, and Abdul’s musical identity as it is remembered now, started coming together more clearly after she and Corfield started working with Leiber and Elliot Wolff (the writer and coproducer of “Straight Up”). Corfield allowed them to produce their own songs, bringing their unique sensibilities, and a willingness to collaborate with Abdul, to the project. “Because the writers were also producing, mostly for the first time, except for L.A. and Babyface, they cared a lot,” remembers Corfield. “They put a lot of time and effort into it. I think that sort of youngness and the greenness of everybody was part of the charm.”

Leiber and Wolff took the time to help Abdul come into her sound throughout the recording process. Leiber found that her natural vocal range “was best when she was actually moving and dancing … I had her dancing to a certain extent,” he recalls of their time in the studio. “On my stuff you can hear shit jingling on some of the songs.”

Abdul would later be remembered — in some ways dismissed — as a Janet Jackson knockoff, because Jackson had first used new jack swing and the funky Prince-style Minneapolis sound as a female pop singer to make Control, two years before Abdul released her debut. Leiber was certainly influenced by and circling the Prince camp while living in Minneapolis; he recorded the demo of the first song he made with Abdul, “(It’s Just) The Way That You Love Me,” with the artist St. Paul, who’d been part of Prince’s bands the Time and the Family.

You could also make the case — and Abdul has — that she helped create Jackson’s dancing style, which remains influential to this day. Referring to Jackson’s choreography, Leiber says, “There was a sense that that was really [Abdul’s] dance style. She gave it away, she was a choreographer, but she kind of wanted to own it. So I knew that the order of the day was to try and make a Janet kind of record.”

As they worked together, Leiber adapted that sound to work with Abdul’s own distinctive persona, particularly with the song “Forever Your Girl,” for which he drew on poppier influences, like Madonna’s “Borderline.” Before working with Abdul, Leiber had started a song, inspired by his girlfriend from North Dakota, called “Small Town Girl.” It was “very upbeat, very major, very poppy,” he says, and he played it for Abdul. “I just got this strong feeling from her of this sort of innocence, a sweetness about her, a timidity about her.”

Leiber wrote the song’s lyrics after their first meeting. “‘Forever Your Girl’ was my take on the sweetness that Paula had and my imagining how she might handle it if she had an insecure boyfriend,” he says. The song later doubled as a declaration of her new status as America’s sweetheart, and it would ultimately become one of her signature hits.

It was Abdul herself who stumbled onto, and strongly advocated for, the funky pop of “Straight Up” and “Cold Hearted,” after her mother got a demo from Wolff, then an unknown writer/producer. Wolff died in 2016, and Abdul spoke at his wake about her reaction to first hearing the “Straight Up” demo. “We were actually crying-laughing, but I was also so intrigued, and my mom said, ‘I'm putting this in the wastebasket,’" she recalled. Abdul pulled it out of the trash, telling her mother, “There's something about it that's crazy good, and I have to hear it again."

“Straight Up,” which inspired countless punning headlines about her upward trajectory at the time, remains Abdul’s most iconic song and the most-viewed music video of any of her hits. Today, it just sounds distinctly of its ’80s era, making it hard to understand why Abdul — or anyone at the record company — might have found the song laughable. But Leiber, who calls the song a “masterpiece” (and Wolff a genius), remembers having a similar initial reaction. “You couldn’t tell, in the beginning, if this shit is really horrible or is it just brilliant,” he says. “His stuff lyrically was campy and comical and not cool, and that’s how it hit me in the beginning, and that’s kind of how it hit everybody. I think that’s why it ended up in the trash bin.”

That campiness is likely what turned off the record company executives. (Abdul said she had to convince them to include “Straight Up” on the album.) “All the world’s a candy store / and he’s been trick-or-treating,” is one of the metaphors of “Cold Hearted,” in which Abdul advises a girlfriend against a player, spitting out the phrase “cold-hearted sssssnake,” a slithering bit of pop onomatopoeia. “That was the stuff that hit my ears and I went, ‘This shit is not cool, and this guy has definitely not been hanging with the brothers,’” Leiber recalls, chuckling.

But Abdul, says Leiber, “was always ahead of the curve. She heard it and she was right: His stuff just has its own thing.” She worked hard with Wolff to get the vocals right, recalling that he went as far as writing out the song phonetically for her. “That’s how I learned how to say the rap,” she explained. “He was meticulous with Paula,” Leiber says. “He just went line by line, vowel sound by vowel sound, and there’s a uniqueness to it.”

Both these songs brought out another aspect of Abdul’s sonic persona, with more attitude and less of the sunny, girlish appeal of the other songs on the album. But “Straight Up” — indeed, all of Forever Your Girl and Abdul herself — might have been lost to history, because the record company slotted Wolff’s song in as a B-side, and went with the more famous producers’ track, “Knocked Out,” as the first single.

“We were initially working her on the R&B side,” says Corfield. Much was made during Abdul’s rise of her ethnic ambiguity, but, as Corfield put it, “she’s a Jewish girl from the Valley, as far as I’m concerned,” and her sound was not “urban” enough for non-pop stations. Babyface and L.A. Reid’s “Knocked Out” failed to gain major video or radio airplay traction on the R&B charts when it was released in the summer of 1988. And the second single, Leiber’s “(It’s Just) The Way That You Love Me,” accompanied by a stylish, big-budget video shot by David Fincher, initially peaked at 88 on the charts. The record company, which was new in America, was giving up on the album. “So I asked, ‘Is the record a stiff or what?’” Abdul later told People. “And the record company said, ‘Paula, it ain’t happening.’”

Ultimately, Abdul’s stardom was not sparked by record company machinations, her choreography, or even MTV, but by old-fashioned radio play. It wasn’t until the end of the year that “Straight Up,” the quirky song Abdul had advocated for, was selected and played by the pop radio station KMEL in San Francisco, and immediately took off. It rushed up to Billboard’s top 20 based on radio, before a music video was ever shot, prompting Virgin to push it as a single. And Fincher’s imagining of the song in the now-iconic black-and-white video, featuring Abdul’s distinctive dance moves, helped define her own kind of hip girlishness. (The Djimon Hounsou and Arsenio Hall cameos didn’t hurt, either). Thanks to the success of “Straight Up,” the other Leiber and Wolff songs were released as singles, and “Forever Your Girl” and “Cold Hearted” both eventually peaked at No. 1. And the album, which holds the record for slowest climb to the top of the charts of all time, finally began its ascent.

Once the momentum picked up, Abdul was able to imprint herself even more on the music, altering “Opposites Attract” to fit her vision for its music video. “She always wanted to do an animation song. She had a bee in her bonnet about it for ages,” recalls Corfield. Leiber originally wrote the song — borrowing the title from a dime store romance novel — as a call-and-response tune between Abdul and Prince backup singers the Wild Pair. “The rap was put on it to be the voice of the cat, because she wanted a video with an animated character,” Corfield says. Leiber collaborated on a rap with a radio DJ he found in Minneapolis, Derrick “Delite” Stevens, who became the voice of MC Skat Kat in the video, “and that was a massive video, and again gave her a number one,” remembers Corfield.

Forever Your Girl went on to sell 7 million copies just in the US, and that massive success changed the dynamic around Abdul, as she suddenly became both a major corporate priority and a public target. Singer Yvette Marine, who Leiber had hired as the demo vocalist for “Opposites Attract,” sued Virgin, claiming that her voice was on the song’s lead vocal. Coming in the wake of the Milli Vanilli backlash and Martha Wash’s C+C Music Factory lawsuit — which prompted an authenticity witch hunt amid public suspicion that music video performers weren’t actually singing their songs — the lawsuit sparked endless bad publicity and reports of Abdul as “the latest lip sync scandal.”

Abdul, who sat front row of the courtroom every day, ultimately won, but the allegations didn’t help her musical credibility. The case made headlines in 1991, just as she was releasing her second album, Spellbound, and fed a larger skepticism about the rise of “manufactured pop” designed to compensate for artists without songwriting skills or big voices. The success of Abdul’s debut also impacted the sound and marketing of her next album, because there was now a big success to live up to and reproduce.

“Everybody was a sweetheart for the first one, but was also green. Everybody was sort of, like, scrambling,” says Leiber. “Whereas there wasn’t really much A&R-ing for the first record, all of a sudden there’s A&R-ing going on, and there’s management going on, and there’s these people making decisions.” Abdul’s new managers — former promotions men — rejected Leiber and Wolff’s input for the second album, and the members of one of their other acts, the Family Stand, became her writers and producers.

Spellbound did eventually hit No. 1 — setting a record as the lowest-selling album to do so — and gave Abdul two more number one singles: “Rush Rush,” a stripped-down ballad emphasizing her vocals accompanied by a Rebel Without a Cause–inspired video featuring Keanu Reeves; and the follow-up single “Promise of a New Day.” But it was also perhaps the first sign that Abdul was losing her grip on the zeitgeist — and musical credibility — as she moved out of the teen pop mold of Forever Your Girl.

The vaguely new-age video and lyrics of “Promise” (“What will change the world / No one knows,” “Hear the younger generation ask / Why do I feel this way?”) came across as an awkward attempt at more adult, socially conscious themes, in the mold of Jackson’s Rhythm Nation, that didn’t fit with Abdul’s image. Critics have singled out her performance of “Vibeology” at the 1991 MTV Video Music Awards as the moment she jumped the shark, because of her “unflattering” costume and her supposedly shaky attempt at live vocals.

Abdul later joked on her reality show that her bedazzled leotard at the VMAs made her look “fat” and nearly ended her career. But it was more likely the long delay between her second and third albums that defused her momentum. Abdul took time off after Spellbound to deal with personal issues, including an eating disorder and her divorce from Emilio Estevez. By the time she reemerged with Head Over Heels in 1995, Corfield says, “She wasn’t as cutting edge … a lot of hipper artists had come up in between. You have to change with the times to stay current, and maybe she wasn’t current; obviously she wasn’t. Her kids, her fans had gone on to the next thing.”

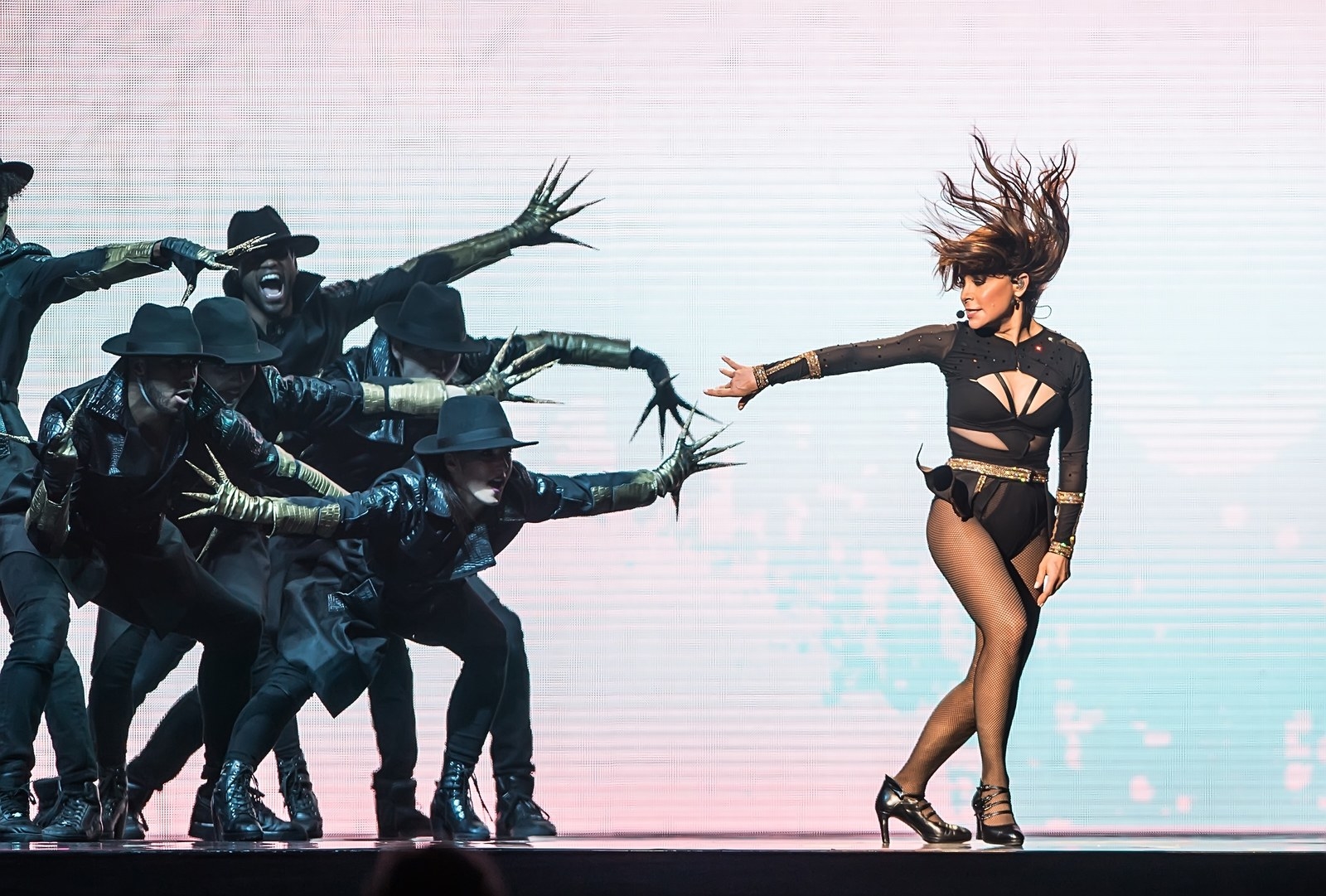

In 2001, Abdul reinvented herself as the reality television star we know today with her debut as a judge on American Idol, and she’s spent the better part of two decades since mentoring budding pop stars and dancers; she pioneered the pop-to-panel move later employed by other divas like Jennifer Lopez, Spears, and Katy Perry. Still, Abdul’s quirky, enduring appeal has helped her music continue to resonate in unexpected ways, whether she’s reenacting “Straight Up” dance moves with Kelly Ripa or providing the soundtrack for a lip-sync battle on RuPaul’s Drag Race. “She’s done well and made a career for herself,” says Corfield, “so she’s got the last laugh, probably.”

Abdul’s short-lived 2007 Bravo reality show Hey Paula is a candid production from that brief window before celebrities wised up and turned all “reality” productions into boringly glossy infomercials. In one scene from the series, as Abdul is walking down the street after an awards show, a random guy in a car screams, “Hey, Paula! You know that you’re a legend!” He cheerfully adds, “Yeah! ‘I’m Forever Your Girl!’ Remember that?” Abdul laughs appreciatively. It’s a bittersweet moment that unexpectedly captures the promise of that optimistic first album title — that even despite pop’s ruthless tides, Abdul could remain eternally ours. ●