The true crime era keeps chugging along with ever more podcasts, YouTube shows, 24/7 crime cable channels like Investigation Discovery and Oxygen, and prestige multipart series, Of course, the splashy series tend to get most of the attention.

Documentaries like Netflix’s The Staircase and Making a Murderer broke out of the pack by flattering viewers with the highbrow sheen of criminal justice analysis alongside the cases they chronicled. More recent Netflix entries like Don't F**k With Cats, about a creepy internet killer, and Tiger King, about a con artist in the big cat world, emphasized the bizarro qualities of their attention-seeking criminal protagonists, raising perennial questions about the ethics of the genre.

Chatter about the aughts true crime renaissance tends to overlook beloved but formulaic network go-tos like Dateline, but another onetime network staple’s comeback feels surprisingly thoughtful. This summer, Netflix went old school, rebooting the low-tech ’90s franchise Unsolved Mysteries series.

The original, which aired on CBS, then NBC, until it was shunted off to Lifetime and canceled in 2002, not only chronicled unsolved crime cases, but unexplained stories, including “paranormal” activity and UFOs. Now, after an 18-year hiatus, it's back on streaming, thanks to its original producers and a co-creator of Stranger Things. Six new episodes dropped this week, and the first batch of six episodes shot to No. 1 upon release in July, and ended up the second-most-streamed show on the platform for the month.

"We didn't want to just produce the same show (from) 20 years ago,” producer Terry Dunn Meurer told USA Today. “We wanted it to be fresh and feel contemporary." The new iteration ditched the rain-coated narrator-host and reenactments for episode-long storytelling. And instead of relying on the usual headline-grabbing stories that dominate the crime market, it builds the kind of confounding threads that thousands of Redditors flock to solve themselves. It also sensitively renders stories of people who aren’t white, featuring victims and families not usually part of the crime industrial complex, a timely reminder of who gets left out of the audience’s — and online sleuths’ — sympathies.

Unsolved Mysteries was part of the first generation of true crime TV, a contemporary of shows like America’s Most Wanted, hosted by John Walsh, who’d become a national celebrity and victims’ rights advocate after the horrific murder of his 6-year-old son. It was through shows like Most Wanted and Unsolved Mysteries that viewers were first turned into proto-online vigilantes, encouraged to phone in tips to catch violent criminals.

Unsolved Mysteries has touted the fact that the franchise has reportedly led to the resolution of 260 cases, but the show has remained more flexible — and adaptable across platforms — than its equally famous network contemporary, Most Wanted, because it was less focused on catching criminals and more on providing the kind of genuinely perplexing stories beloved by conspiracy theorists and true crime obsessives.

The multiplicity of voices and angles — rather than a narrator — adds to the immersiveness of the storytelling.

The new streaming version features an anthology of bingeable, tightly packed episodes that feel like contained podcast episodes in TV form. They’re deeper, more haunting, and less cheesily produced than your average Investigation Discovery show, but not as consuming and immersive like The Staircase or Hulu’s current A Wilderness of Error that viewers must devote hours to.

While the 12 episodes released so far focus almost exclusively on crime stories — save for two that have a more paranormal bent — they’re not your usual revisitations of overly covered cases like Chris Watts and Madeleine McCann. Each episode instead features the kind of multipronged stories that have the endless potential explanations Redditors love to speculate about. And rather than replacing the late Robert Stack with a new host to help viewers navigate these crimes, the series relies on the voices of friends, victims, or firsthand observers to help unspool the mysteries. The multiplicity of voices and angles — rather than a narrator — adds to the immersiveness of the storytelling, and the sense that there isn’t one single explanation for what happened.

The first episode involves a French case that will probably surprise American audiences, about a count who seems to have systematically annihilated his family in Nantes, buried them in the backyard, and is still on the run to this day. As friends testify about what he was like as a person, and raise questions about where he might be, the story juxtaposes haunting footage of him saying goodbye to a security camera.

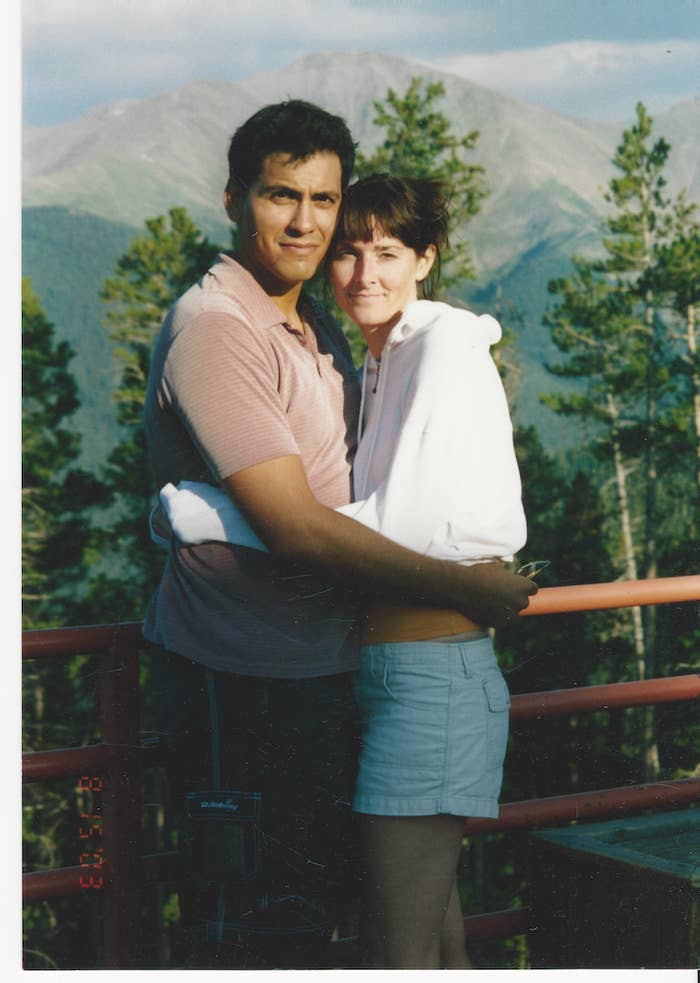

In another episode, a Latinx aspiring filmmaker, Rey Rivera, plunged to his death from Baltimore’s Belvedere hotel rooftop and left what some investigators believed was a suicide note. His wife doesn’t believe the theory, and she attempts to unravel the mystery. Did Rivera actually die by suicide or was he murdered, perhaps as part of some conspiracy by the shadowy company that employed him? Of course, there are already Reddit threads about it.

In one of the newest episodes, one story about a woman — still unidentified to this day — who died in a luxury hotel in Oslo initially seemed banal, but is actually emblematic of the way the show expertly builds suspense. She was discovered with a seemingly self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head after a hotel receptionist realized her credit card wasn’t on file and sent security to check on her. As the journalist who originally wrote about the case becomes another character — and not a disinterested narrator — pointing to all the inconsistencies that grabbed his attention, it feels impossible not to be pulled in.

He points to the fact that her hand was grabbing the gun in a way that seemed staged, and that, because of recent peace talks, the hotel had hosted high-level government security professionals. She had checked in under a false name, but perhaps most unusually, her clothes had been rendered label-less so their make or manufacture couldn’t even be traced. (Semi-spoiler alert: By the end you’re left wondering if she was a spy and her family paid off by the government.)

The crime genre has been notoriously defined by deeply white cultural politics, including an exclusive focus on white, middle-class protagonists, who are also often the imagined audience. Insecure’s show-within-the-show Looking for Latoya is a darkly humorous critique of the genre’s class and race politics.

Through its careful story selection, the new Unsolved Mysteries flips the script to some degree, centering stories about working-class people, and people of color. In one episode, 23-year-old Alonzo Brooks, who is Afro-Latinx, goes to a party with some white friends in rural Kansas and never comes home. His body was later found but it wasn’t possible to determine the manner of death. His family, especially his mother, Maria Ramirez, is certain a crime occurred, possibly even a hate crime based on racist comments made at the party.

The episode sparked its own Reddit threads and has already prompted new leads and further FBI involvement in the case, including an exhumation of his body. The show has actually explicitly engaged Redditors, using Google drive to dump evidence from the cases that didn’t make it onto the show. Each episode also ends by encouraging viewers to provide tips or leads.

This kind of overt engagement with or encouragement of sleuths has long been one of the many troubling ethical conundrums of the crime genre. Shows like Mysteries and America’s Most Wanted and its “see something, say something” ethos encourage a kind of surveillance and vigilantism that is already endemic against people of color. And the real problem with the criminal justice system is not that some people don’t get caught, but the systematic bias against Black people and other people of color.

And while Unsolved Mysteries is not necessarily interested in raising deeper questions about racism in the criminal justice system — a hallmark of recent true crime — it does attempt to tell more stories that aren’t focused solely on middle-class white people. One of the anthology’s less Reddit-friendly episodes focuses on two Black mothers in New York City whose toddler sons were snatched at a park within months of each other.

One of the mothers points out how rumors and media coverage at the time victim-blamed her, implying her past issues with addiction might have had something to do with the child’s disappearance. It’s an implicit critique of the ways that crime-solving through rumor and audience sleuthing is always playing on already existing ideas about, say, motherhood and Black mothers as unfit. Similarly, Alonzo’s mother’s palpable frustration about the way her son wasn’t protected by his friends — or how his case was handled by authorities — speaks to the way young men of color aren’t seen as innocent and worthy of protection.

The politics and ethics of true crime will always be complicated. Not just because, as is often suggested, it involves the commodification of pain and tragedy, but because it feeds into existing ideas about crime and punishment, about who deserves redemption and innocence and who doesn’t. The new Unsolved Mysteries invites viewers not just to endlessly interpret crimes, but, in a small way, to think about the people left out of the zeal for justice. ●