There is an unintentionally funny moment in Mariah Carey’s new E! show, Mariah’s World. “Here’s the thing,” she tells viewers earnestly during a confessional, “for me, it’s always been about the music first.” Reclining on a chaise longue in a sparkly showgirl corset, legs artfully draped to the side, her appearance tells a different story. It suggests that her persona — rather than her music — has become the main focal point of her career.

Much like her Instagram account — in which she is photographed wearing a gown on a subway — or her memorable 2002 MTV Cribs episode — where she works out in high heels — Mariah’s World comically repackages her kitschy idiosyncrasies as television content. Yet her insistence that she exists in some authentic space beyond these spectacles of excess captures the contradictions that are an inescapable part of Mariah’s persona.

Is she Mimi, the melodramatic pop star who Miley Cyrus dismissed in Elle magazine’s October issue? Or is she still “The Voice,” as talk show host Wendy Williams called her in a spirited defense, asking Cyrus to respect the vocal virtuosity that many fans remember from Carey’s early years? Pop stars can be many things, but in order to maintain success they must reconcile or make a case for the contradictions of their personalities with compelling pop theater and narratives.

Throughout Mariah’s musical domination of the '90s — in songs and videos like “Fantasy,” “Honey,” and “Heartbreaker” — she transgressed lines between black and white, pop and hip-hop, seriousness and frivolity. But much of the public and many critics interpreted Mariah’s boundary-breaking as artistic and professional disarray, and she was often portrayed as loopy or crazy. By the time of 2001’s Glitter — her autobiographical movie and soundtrack project that flopped in the midst of the most scandalous pop diva meltdown before Britney Spears — Slant magazine argued that she had “kitsched herself into oblivion.”

In the aftermath of her mid-2000s comeback, a new generation of critics reconsidered her musical influence. Sasha Frere-Jones and Carl Wilson wrote about the influence of her melismatic vocal style. Jody Rosen argued that her schmaltzy ballads should be placed in historical context. They all point to the influence of her pop and hip-hop boundary-breaking through what Kelefa Sanneh calls the thug-love duet.

But these critics gloss over Mariah’s messy attempts to represent her contradictions, including the liminal nature of her biracial identity and her knowing, winking hyper-femininity. These aspects of her persona are central to understanding both the success and failures of the art of being Mariah, from the hip-hop collaborations, to the Glitter flop, to her reality television era. They are integral to appreciating why she matters, why she is overlooked, and how she paved the way for pop divas as disparate as Ariana Grande and Katy Perry.

As a mixed-race diva, Mariah has often struggled to stage the complexities of her identity in public. She has talked about the difficulties of being a biracial child, born to a black Venezuelan-American father and an Irish-American mother on Long Island. “I remember being with my father and people looking at him like, 'Did you kidnap this kid or something?' And being with my mother and people looking at us and thinking, 'Why does she look darker?” she told the British magazine Pride in 2001. Being both too white and too dark in her homogenous surroundings turned Mariah’s body into a site of confusion, anxiety, suspicion, and even disgust (a classmate once spat on her during a bus ride).

Such childhood anecdotes might help explain why, when she landed a record deal with Columbia Records at 19, after being discovered and signed by CEO Tommy Mottola in 1989, she agreed with the record company’s plans to put forth a conservative image that would foreground her voice and obscure her racial identity.

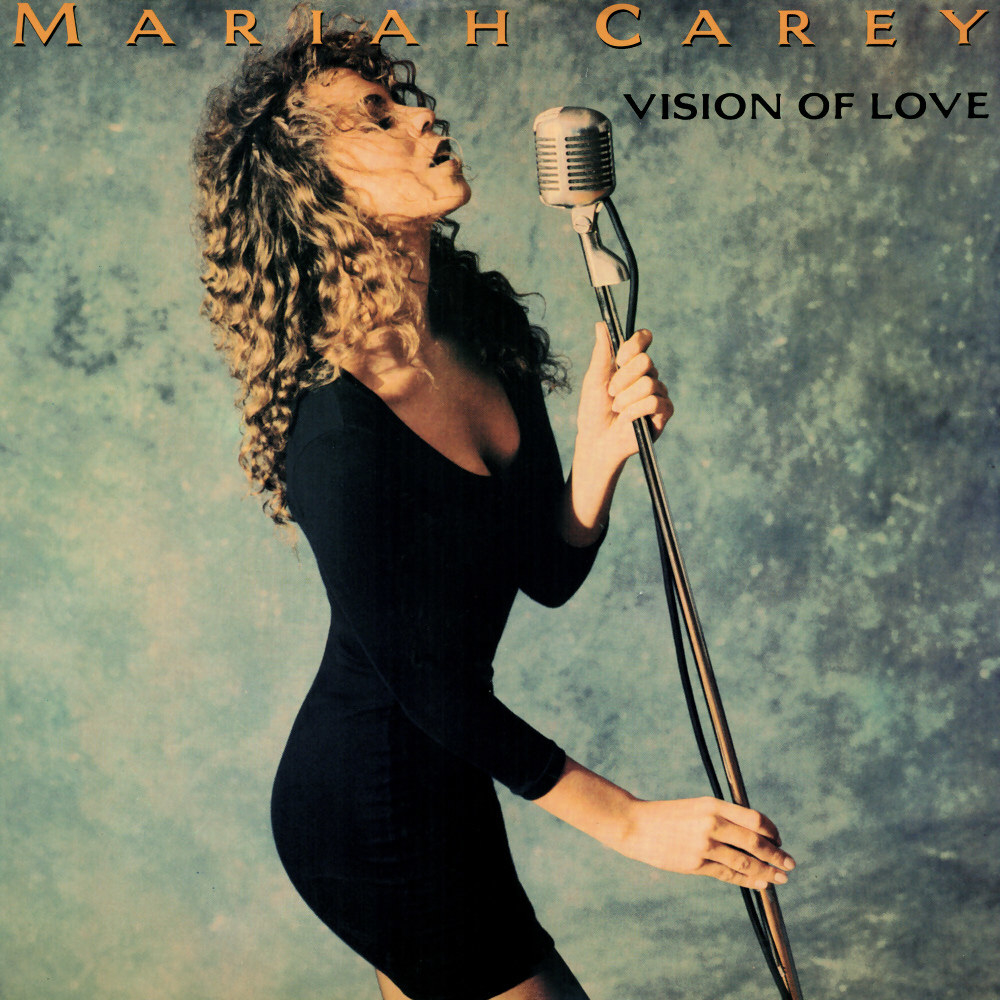

Initial promotional photos showed off her curly golden-brown hair, as she wore a little black dress and held a vintage microphone, suggesting that her voice was the main attraction. By containing her persona within the minimalist “classy” appeal of the little black dress, a fashion staple made famous by Audrey Hepburn, the images also presented Mariah’s femininity in a way that suggested an urban — but white — sensibility.

After label execs chose the gospel-tinged “Vision of Love” as the first single off her 1990 self-titled debut album, two music videos were shot. The first one — never released— reportedly featured her in a bra lying on her bed. Mottola disliked the video’s explicit sexuality and ordered a second version, an artless Hallmark-card video that helped take the song to No. 1 and set the stage for Mariah’s conservative imagery.

Mariah's brand of big-voiced innocence led to frequent comparisons to Whitney Houston, but also caused controversy.

This brand of big-voiced innocence led to frequent comparisons to Whitney Houston, but also caused controversy. Writing in Playboy magazine in November 1991, the music critic Nelson George dismissed the comparisons as marketing hype and called Mariah “the Debbie Gibson of soul.” He meant that Mariah — who George believed was white based on Columbia Records’ ambiguous promotional materials — was an inauthentic borrower or performer of black culture. Though she clearly stated in interviews that she was mixed race, many journalists believed the record company was trying to obfuscate the issue. Village Voice columnist Lisa Jones argued that Columbia Records attempted to “pass” Carey as white in her 1994 book, Bulletproof Diva. After her album launch Columbia set up a luncheon with black journalists — partly instigated by George’s article — to dispel the controversy.

Yet her biracial heritage remained a troublesome cultural dilemma. Because she had no straightforward story to tell about her identity, Mariah’s racial authenticity was always in question. And the invocation of Debbie Gibson, perhaps the symbol of white-bread suburban girlhood, made clear that this inauthenticity was inseparable from her femininity. She would be contesting this understanding of her persona for a long time.

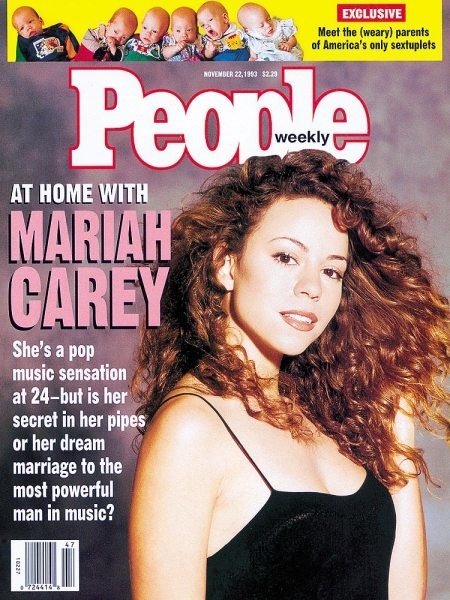

Although Carey’s first two albums sold well, she only became a blockbuster pop diva after the massive success of her third album, 1993’s Music Box. Its success was contingent upon her playing the role of the demure vocal powerhouse, and it was a persona that extended her growing celebrity; People magazine’s first 1993 cover story of her was a puff piece about her “dream marriage” to Tommy Mottola.

The album and story appeared as Mariah was privately accusing Mottola of turning her into the 1950s teen pop princess Connie Francis, i.e., prim, youthful, and white, according to his 2013 memoir Hitmaker. The black and white portrait of her on the cover of Music Box rendered her brownness invisible, while the album’s sounds smoothed over the racial ambiguities that Mariah wanted to explore.

When she initially wrote the song “Dreamlover,” for instance, alongside hip-hop producer Dave Hall, it had a stripped-down minimalism, with little background chorusing or harmonies. Mottola decided it wasn’t pop enough and in-house producer Walter Afanasieff was brought in to add “sprinkles and sparks” and turn it into a straightforward pop tune. Similarly, she wrote “Hero” — another classic of the “girl in the gown singing ballads” era, as she calls it — for a Dustin Hoffman movie. But Mottola requested its inclusion on her own album after he heard the demo, and when Mariah tried to add a gospel flair to her version, he insisted that she keep the gospel vocals in check to make it pop.

The massive success of “Hero” and “Dreamlover” helped Music Box reach No. 1 not just in the US but globally. It became her best-selling record to date, going diamond in the United States — meaning 10 million copies shipped — with 23 million copies sold worldwide. Daydream followed in 1995 with its own “Hero”-style schmaltzy ballad (“One Sweet Day”) and the “Dreamlover” remake “Fantasy,” which debuted at No. 1 — the first single by a female artist to ever do so on the Billboard Hot 100. The album sold 20 million globally. Mariah Carey — or at least one version of her — had become one of the best-selling pop divas in the world, on par with Madonna and Whitney Houston.

The music and persona that took Mariah to the top were a defensive attempt to smooth over potential racial contradictions through a form of “proper” femininity, lest she appear too “urban.” But she had already started — in her own way — to slowly shift the racial center of pop with the hip-hop remix of “Fantasy.”

It has become commonplace for critics to argue that Mariah’s 1995 “Fantasy” remix with Ol’ Dirty Bastard — produced by Sean “Puffy” Combs — pioneered or popularized the once-dissonant idea of weaving a rap interlude into a sweet pop song. But it’s important to remember that this collaboration worked because of — not in spite of — her demure early image. Mariah never used hip-hop in the mode of Madonna, who exploited the specter of black male sexuality as a white woman to appropriate an aura of authenticity and transgression (in songs like “Erotica” or “Secret,” for example).

Instead, Mariah used her cookie-cutter image as a bridge to make hip-hop unthreatening to new audiences. The humor of Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s line (“Me and Mariah / Go back like babies and pacifiers”) works because of its preposterousness, and his acknowledgment of his part in keeping her “fantasy hot like fire” was almost like a meta-commentary on the song’s role in Mariah’s career. Even the music video — which she directed — was a child-friendly affair: Set at an amusement park, it featured a clown and a roller coaster ride, and helped maintain her multigenerational appeal.

After her 1997 divorce from Mottola, Mariah was finally able to assert full control over her music and, more importantly, over her image. Paradoxically, while the post-divorce records Butterfly (1997) and Rainbow (1999) are often mocked for the girlish sensibility of their titles, they are two of her most visually and conceptually ambitious albums and pop events. Because she stopped relegating rap interludes to hip-hop remixes — they were on the official lead singles of Butterfly (“Honey”) and Rainbow (“Heartbreaker”) — she was finally forced to make a case for her new music to her entire audience, through a new image.

She opted for a campy femininity that more fully captured her taste for parody and humor. And it was through that sensibility that she started to move away from previous identity constraints and explain the contradictions of her persona. The “Honey” video, for example, used a James Bond spoof to tell the story of her escape from an oppressive marriage into the freedom that allowed for such a video in the first place. It is probably not an accident that she chose to play the bronzed, bikini-clad Bond Girl agent Honey, for it allowed Mariah to emphasize the brownness of her tanned skin, which was brought out through its contrast with her white outfits and white backgrounds throughout the video.

The video for 1999’s “Heartbreaker” also illuminated Mariah’s new relationship to the boundaries of race and gender that had defined her. In the video she plays the part of a high-maintenance girlfriend whose boyfriend, played by Jerry O'Connell, cheats on her. In the video she camps it up by playing Sandy, the ultimate symbol of white innocence from the 1978 movie Grease, essentially telling us that her demureness was always an act, as fake as the platinum blonde wig she wears in the video.

But perhaps it was the 1999 Rainbow album cover, created by neo-Warholian photographer David LaChapelle, that best allowed for the disparate elements of Carey’s persona and aesthetic to flamboyantly come out. The photograph features a tanned Carey — again fully emphasizing her brown skin — in pristine white panties and a tiny T-shirt, with rainbow graffiti (one of the component art forms of hip-hop culture) spray-painted across her chest. The back cover displays her backside similarly spray-painted, and Carey holds a lollipop close to her mouth. It brilliantly captures, and keeps in tension, all of Carey’s contradictions: her combination of pop and hip-hop, high and low culture, nearly graphic nudity (you can even make out the details of her buttcheeks on the back cover) juxtaposed with girlish innocence. The rainbow symbol — evoking both the multicultural rainbow coalition and gay pride — was meant to represent, as Mariah wrote in the album’s liner notes, the peaceful coexistence of the supposedly inconsistent aspects of her identity. Whether they appear to be in harmony or disharmony in that provocative visualization of trashy Americana is ultimately up to the viewer.

But it is easy to miss the transgression of Mariah’s feminine theatrics because her style is always sweetly tongue-in-cheek, girlishly in between rather than in your face. Madonna’s scandal, for example, involved playing with signifiers of masculinity in feminine terms, whether she was grabbing her crotch or rubbing those threateningly pointed cone bras. Mariah prefers reclaiming discredited hyper-feminine forms, even stating in a 2002 interview that she never dreamed of being a man: “I'd probably be a drag queen. I've never wanted to be a man. I don't have those fantasies of wanting to be one...I live for girl moments.”

It is easy to miss the transgression of Mariah’s feminine theatrics because her style is always sweetly tongue-in-cheek, girlishly in between rather than in your face.

This femininity is inextricable from her racial and musical identity, and it was a major aspect of the backlash against her. White comedians ranging from Sandra Bernhard to Howard Stern joked about Mariah’s “new” blackness and mocked her interracial identity, often in sexualized terms about her desire for men of color. Bernhard in particular implied that Carey was somehow looking for sexualized “street” credibility by sidling up to Puff Daddy. “Yeah, Daddy,” Bernhard says, imagining Mariah in a coyly sexy “white girl” voice during her 1998 stand-up special I’m Still Here!...Damn It!, “I got some black in me too.”

During the release of Rainbow, Mariah blamed the media for confusing the public about her work, telling British magazine Hip-Hop Connection, “A lot of the time they form the idea in listeners' minds. Calling me a ‘pop’ diva without listening to my work, so when I come out with an, ‘in-quotes’ urban song it's like, ‘Pop diva goes black.’ I mean, pur-lease.” But it wasn’t just her fusion of pop and hip-hop that confused her audience, it was also the unsettling, unapologetic girliness of her style. The combination ultimately fragmented the audiences that her conservative image had kept together, and this complex persona could not match her earlier commercial success.

In fact, her album sales started to dramatically decline throughout the late '90s. While Music Box and Daydream went diamond in the states, Butterfly went five times platinum, and Rainbow went triple platinum. These might have been huge numbers for any other artist, but given Columbia’s investment in Mariah, they were seen as sales disappointments rather than transgressive explorations of identity.

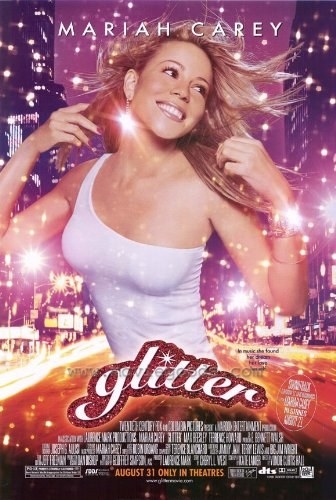

In 2001, she acrimoniously left Columbia, amid accusations that Mottola was underpromoting or sabotaging her career. She arrived at Virgin Records with a record-breaking $80 million contract and enormous expectations. But her precarious balancing act — between the new kitschy aesthetic, the representation of her mixed-race identity, and the success expected from her by record companies — finally came to a head with Glitter, the movie and soundtrack album project that nearly derailed her career forever.

The public tends to think of Glitter as a hot mess that deserved to flop. But the project makes more sense in retrospect, when viewed as part of Mariah’s ongoing conflict around her public representation. While devoted fans — whom she calls Lambs, or the Lambily — knew about the personal turmoil around her biracial identity (through album cuts like “Looking In,” “Outside,” “Close my Eyes,” and “Petals”) she had never made that struggle an explicit part of a lead single or music video.

Glitter was supposed to finally change that. Though often framed in the press as a remake of A Star is Born, which was a vehicle for white pop divas like Judy Garland and Barbra Streisand, Glitter was also deeply influenced by Purple Rain, the 1984 musical drama in which Prince plays the conflicted son of a dysfunctional, mixed-race couple. That fictional story served as a kind of metaphor for the interracial funk rock Minnesota sound that became Prince's trademark — and perhaps Mariah hoped Glitter could do the same for her.

She decided to move the setting to the ’80s club scene in New York City. Her character, Billie Frank, is a backup singer for Sylk (played by Top Chef’s Padma Lakshmi), a protégée in the mold of Prince’s Apollonia: lacking a great voice, but making up for it with a powerful manager and the right producers. When one of those producers discovers Frank, melodrama ensues. The setup could have provided an opportunity for a thoughtful exploration about musical and racial authenticity that Mariah herself had dealt with throughout her career. But in the final cut, the movie was neither a fully over-the-top kitschfest, nor the “gritty” story Mariah originally envisioned. Instead, the studio “watered down and homogenized” the project, as it was decided that the film should be a “family movie” geared toward all audiences. In other words, it would be edited and marketed for Mariah Carey’s “Hero” audience.

Paradoxically, this forced homogenization was precisely part of what the film was originally about. Traces of its initial impetus remain, and perhaps that is why the only interesting — and funny — line in the whole film is about Mariah’s character’s mediated racial identity. When Billie Frank’s first music video is shot, a British music director says: “We ask ourselves: Is she white? Is she black? We don't know. She's exotic. I wanna see more of her breasts.”

More spectacularly than ever, Mariah was unable to reconcile the disparate audiences she had appealed to at different moments of her career. In his 2010 memoir Guilty by Association, Damion Young, one of her hip-hop producers, noted that the clueless new record company, Virgin, ruined the launch of the movie’s soundtrack and the momentum of its lead single by releasing the rap version of “Loverboy” before the pop version, alienating Mariah’s pop fans.

But these problems surrounding her inability to fit into designated music industry categories were interpreted instead as artistic failures. Even Billboard, usually an industry and artist cheerleader, was uncharacteristically harsh about the song: “The mighty may have fallen here.”

The rest is history; both the soundtrack, but especially the movie, flopped massively. The film grossed only $4.2 million on a $22 million budget. Mariah became a national punch line for late-night talk show hosts: “Reports suggest that bin Laden is most likely hiding out somewhere remote and barren, where he will not encounter others. The FBI has begun searching theaters showing the movie Glitter,” quipped Jimmy Fallon on SNL. Mariah lost all control of her public narrative, unable to transcend the fiasco’s stigma for years.

After the Glitter catastrophe Mariah retreated back into the demure ballad mold with her 2002 album Charmbracelet. But her 2005 comeback record, The Emancipation of Mimi, was seen as a departure: an unambiguous embrace of her blackness and hip-hop sensibilities. This perceived push towards authenticity gave her the biggest sales since the Daydream era — 6 million albums sold — and her first Grammy trophies in the R&B category. With her subsequent 2008 album, E=MC² she lampooned her ditzy image, and once again revealed her contradictory ambitions. While the title alludes to the idea of a sequel or formula in order to ensure major record sales, everything — from the cover portrait of Carey draped in white fur-lined fabric to the lead single “Touch my Body” — suggested a return to the whimsical style of the (low album sales) Rainbow era.

As Mariah appears in a surreal world playing her celebrity self, literally winking at the audience while walking next to a unicorn, she reminds the public that she embraces the joke.

Featuring childlike twinkling piano keys and music box sounds, the airy perfection of her vocals as she coos delicately in her head voice, and the melodramatically desperate vocal runs at the end, the single highlights the campy qualities that were largely bracketed in Emancipation. And, in the accompanying video, as Mariah appears in a surreal world playing her celebrity self, literally winking at the audience while walking next to a unicorn, she reminds the public that she embraces the joke.

While the album was No. 1 on Billboard, sales declined to 2 million, and “Touch my Body” remains her last No. 1 single. Still, this version of Mariah, unembarrassed about, and even winking at, her racial and sexual ambiguities, now seems here to stay. Whether donning male drag to parody Eminem and using Mean Girls references to mock him in her 2009 top 10 hit “Obsessed”, or coyly grabbing her crotch on a motorcycle while dancing for Miguel in 2013’s “#Beautiful,” she seems to have permanently rejected the minimalism of her earlier image. Instead, she’s opted for a public exploration of the complexities of her identity. She poked fun at the schmaltzy inspirational aesthetics of her song "Hero" in an over-the-top commercial for the popular mobile roleplaying game Game of War in 2015 and parodied her reputation as a self-involved diva earlier this year in the Lonely Island mockumentary Popstar.

Mariah has even made public peace with Glitter, telling Andy Cohen on Watch What Happens Live in 2013: “You don't understand, for years it was the G-word, nobody could talk about it; now I understand it as a kitsch moment in my life.” She performed its off-kilter lead single, “Loverboy,” live for the first time in her entire career during her Sweet Sweet Fantasy Tour in March.

In many ways, that performance symbolized Carey’s ability to make a space for the contradictions that have been the source of both her brilliance and her painful failures. And those contradictions turned into a generative force for artists who grew up with her sounds. Ariana Grande stepped into the shoes of Carey’s early persona of authentic vocal virtuosity and, even if she cannot quite capture its full power, she reproduces the delicate malleability of The Voice in a way no other pop diva has before. The multicultural girl group Fifth Harmony's 2015 song "Like Mariah" celebrates all the aspects of Carey’s music, sampling the innocently soulful shoop-shooping of “Always Be my Baby,” nodding to the kitschy lyrics of “Touch my Body,” and featuring a rap interlude by Tyga. The video for Katy Perry’s 2014 kitschy hip-hop song “This Is How We Do” features a drag queen Carey impersonator even as the lyrics reference the musical impact of Mariah “Carey-oke”; Perry’s girlishly high register in her single “Birthday” purposely evokes the coy Mariah vocals of “Heartbreaker,” and she re-enacted what she called Carey’s “iconic love giggle” from “Honey” on the same album, Prism.

It is often said, intended as criticism, that Mariah Carey lives in her own time, even her own reality. But our culture is finally catching up with her. It is not an accident that Mariah’s World is full of clips of Mariah moments from the Rainbow era — including the "Heartbreaker" video — because reality television is the perfect stage for the campy contradictions that define her.

Early on in the show’s first episode, Mariah's artistic director lectures her about her audience: “They wanna see ass, they wanna see tits — people never feel like you’re accessible to them.” She replies skeptically, “Then they say they want her to be grand! Oh they want her to be accessible! They want her to have glamorous clothes! They don’t want her to have glamorous clothes! Can people make up their minds?”

As she moves through all those incarnations on the show, it is clear that she no longer has to choose, and can embrace the in-betweenness that is her complex legacy. It might be too late to help her reclaim the commercial heights she seems so conflicted about achieving, but perhaps finding the space — and courage — to succeed on her own terms might be the most transcendent form of pop justice for Mariah.

Want more of the best in cultural criticism, literary arts, and personal essays? Sign up for BuzzFeed Reader’s newsletter!

If you can't see the signup box above, just go here to sign up for BuzzFeed Reader's newsletter!