In the opening scene of Jawline, 16-year-old aspiring social media star Austyn Tester poses for a friend as he tries to capture the perfect shot for his daily Instagram post. “Tell me something funny so I’ll laugh,” he says, poofing out his beach-wavy hair as he poses in front of a brick wall in a grassy meadow. One picture is too sunny; another is too close; a more high-concept one where he stares at his own shadow is also deemed unacceptable. Ultimately none of them work, and he and his friend sprint across the grass to their next activity.

That opening scene — a reminder that “being yourself” online is actually work — captures the intimate and nonsensationalist flavor of this new Hulu production. Thanks to sponcon controversies, beauty YouTuber drama, and photoshop scandals, the general public and mainstream media have become (reluctantly) fascinated with the behind-the-scenes goings-on of the world of influencers, if mostly to focus on the absurdity of their dumb gaffes and vapidity.

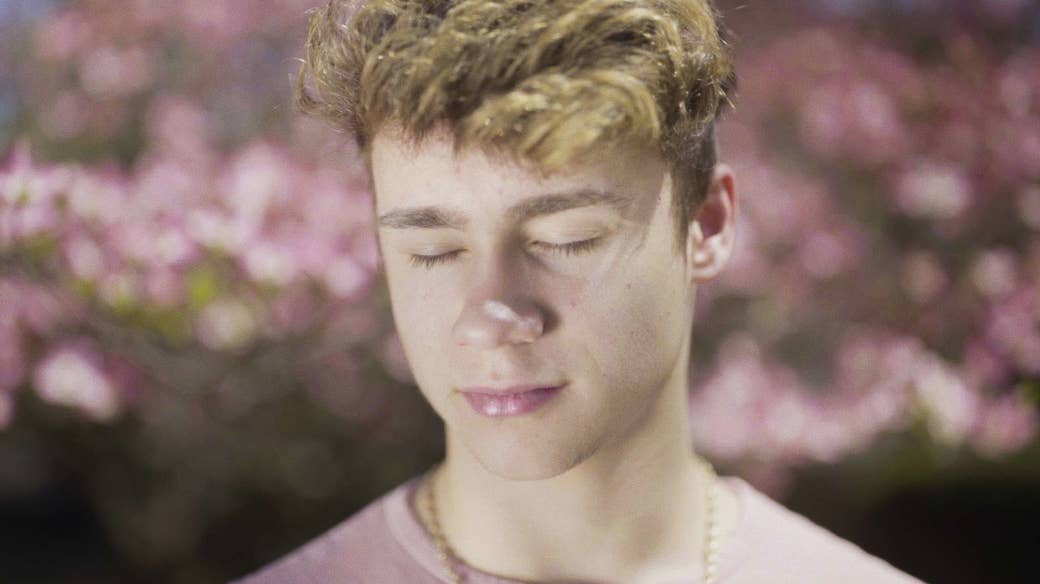

Jawline, directed by Liza Mandelup, smartly sidesteps that kind of mockery. The documentary mostly chronicles Austyn’s journey — it’s his face on promotional materials — through the ups and downs of social media stardom, giving us access to his emotions and personal experience. It captures the labor involved in being a social media personality, from the performances required from the stars, to the needs they fill for fans, to the strategies deployed by savvy managers.

But for all the film’s strengths, the nearly exclusive focus on Austyn’s personal story means that the narrative sometimes veers into clichés about the pitfalls of stardom. The insistent emphasis on his journey leaves less room for focusing on the newer, more interesting aspects of the influencer economy — like the gendered dynamics of teen girl fandoms and the ruthless, unchecked power of tech platforms — that actually allow for Austyn’s dreams of social media stardom in the first place.

Jawline is at its best when capturing the dreary work of being a rising influencer. Austyn, from Kingsport, Tennessee, is white, blonde, and cute, but he doesn’t aspire to the Logan Paul style of assholery and hijinks. Instead, he aims to carve out a cuddlier brand of positivity geared toward teen girls.

At the time of filming, Austyn had around 20,000 followers on Instagram. We see him modeling his career after successful teen twin brothers Julian and Jovani Jara, YouTube stars of the self-help variety who emerged from YouNow and TikTok (they eventually became DJs and music producers). Austyn, too, tries to build his own brand through the platform YouNow, where he interacts with girls who flock to his live broadcasts, hungry for his charismatic bromides and his assurances that they’re beautiful and unique. “That’s what makes us beautiful: We’re one of a kind. We’re different,” he tells them as an uplifting sign-off.

Austyn’s small-town ingenue journey is intercut with footage of a savvy Los Angeles–based manager in his early twenties, Michael Weist, who runs a house full of teen boy influencers he’s trying to make into bigger stars. “Right now it’s like literally the social media gold rush,” he tells us with a kind of shameless hunger. He spots promising influencers, and his goal is to “take them, rebrand them, monopolize that, keep quality control up and more money in my pocket.”

He’s portrayed as a kind of gay Svengali, and his specialty seems to be molding teen boys with promising social media profiles into testosterone-fueled stars of the Logan Paul variety. He uses his Hollywood Hills home like an influencer frat house; in one scene we see the aftermath of one of their parties, complete with fast-food wrappers and half-empty bottles of Ciroc.

As with Austyn’s storyline, the most revealing scenes of this arc involve the real work the boys have to perform to achieve higher levels of stardom. Weist coaxes his aspiring influencers — the bro-y personalities Bryce and Mikey — into posting endless content by making them salads or taking them shopping on Rodeo Drive. Some of the content they produce is for sponsors, like an Old Navy ad involving a scenario about back-to-school backpacks that Bryce has to improvise on — another reminder that the job of "being yourself" on social media actually involves a certain level of performance skills.

Some of the documentary’s other most insightful scenes focus on the fans who drive the influencer world. In Kingsport, Austyn creates his own meet-up at a mall with a gaggle of excited followers. These teen girls pay him a few dollars to ride an electric stuffed animal through the mall, and then demand his cellphone number before leaving. Though he can deal with their attention behind a screen, he seems overwhelmed with the directness of in-person interactions with paying customers who have a crush on him, without a manager to mediate it.

Austyn is eventually signed by the same manager as the Jara brothers and he goes on tour as a kind of opening act for them. We see more of the teen girl angst that drives young women into soothing, reparative relationships with these boys next door — relationships, one-sided as they are, that require paying up to $250 to have real time with them at the influencer conventions.

One girl explains that she is mocked for her hair at school and is assuaged through the Jara brothers’ positivity; another one tells us that her dad is in jail and the Jara brothers are like the brothers she never talks to. One supportive mom agrees, calling the brothers “hysterical,” and says that her homeschooled daughter benefits from watching and interacting with them. Their testimony illustrates the way these nonthreateningly boyish social media personalities, all of them baby-faced with floppy hair, fill real emotional needs.

Starry-eyed teens still want to move to Los Angeles; but instead of being movie stars, they want to become rich and famous just for being themselves.

But the complexities of race and gender in the industry — and the fandom — are ultimately overlooked. Mikey and Bryce, for instance, seemingly have to be coaxed into considering how to best connect with their teen girl fans. In one scene, Weist asks Mikey not to address his fans as “guys” because he might alienate the girls who watch them. These guys seem to fill a different niche — less geared toward positivity or girls’ emotions — than the Jara brothers or Austyn do. But we never actually hear from their fans, which means those nuances don’t get teased out. And though there have been many critiques of the whiteness of the influencer industry, race is not even acknowledged.

Instead, the film spends a lot of time sketching out Austyn’s family background. We meet his exhausted working-class mother, and his older brother who loafs around and smokes weed and wants to live vicariously through Austyn, hoping he’s his ticket out of town too. His father, who abandoned them, was abusive, and the two brothers recall some of those experiences.

Given the usual emphasis on the scandals of wealthy white women influencers, the filmmaker’s decision to focus on a working-class white teen from small-town America is an interesting departure. (And perhaps an attempt to make the zeitgeisty social media narrative resonate on another level as a story about the forgotten white working class.) That focus on the journey for Austyn — and his family — is dramatically effective, but the film doesn’t carry that analysis or nuance into the bigger, more industry-specific questions.

We feel for Austyn, for instance, when we see him at the end of the film working at a clothing store, afraid to go back to school since he didn’t make it after his big celebrity moment. But it’s never made quite clear how, exactly, Austyn failed. We see him thriving on the tour with the Jara brothers, but we later hear from Austyn’s mom that his manager gave him “very negative” feedback. He becomes depressed, stops posting as much, and his follower count and engagement starts falling. He eventually admits that he feels cheated out of getting paid by the manager, who drops him. Perhaps because they didn't get access to Austyn’s manager, the filmmakers have Weist dismissively comment on Austyn’s unimpressive stats and low fan engagement.

Weist’s own stars — Mikey and Bryce — break off from him after seemingly accusing Weist of sexual harassment, and we see him pivoting to work with a “more talented” teen who can sing. (The comment comes off like an attempt to diss his former clients, because he also points out that influencers “peak” at 30.)

In a telling moment, Weist calls Instagram the most “prestigious and secretive” platform of all, and he points out that his competitive advantage is having an in with platforms, from getting the “artists” (as he calls them) verified with a blue checkmark and properly promoted. But we don’t get any insight into the way the platforms themselves — YouTube or TikTok or Facebook — ultimately make the real money, even as the most successful creators struggle with the impossible standards of churning out consistent content.

The film’s storylines suggest that unscrupulous managers and naive talent are the problems with the influencer economy. But those were problems in the entertainment industry long before social media. Starry-eyed teens still want to move to Los Angeles; but instead of being movie stars, they want to become rich and famous just for being themselves. And managers will always put themselves first.

In some ways, Jawline is so in thrall to those old narratives that it sometimes fails to explore what is actually new about the hopes and dreams of fame in the social media age — including the fans who keep the machine running, and the tech overlords who get to remain, in this telling, comfortably behind the curtain. Still, its sober approach is a welcome change of tone for coverage of an industry that — whatever anyone thinks of it — is here to stay. ●