“What do you think the teacher's gonna look like this year?” asked rockers Van Halen in the 1984 MTV-era hit, “Hot for Teacher.” Channeling the perspective of a horny student, the song was a distinctly ’80s ode to the recurring fantasy of the sexy woman educator.

Whether spelled out in the macho theatrics of hard rock or portrayed through literal porn, the trope still looms large as an object of sexual fascination. Even the media’s obsession with real-life teacher scandals in the aughts seemed designed to feed into male-gazey reveries. The biggest stories always featured blonde, young, conventionally pretty women, like Mary Kay Letourneau and Debra Lafave. Lafave, a 23-year-old Florida instructor, was the subject of primetime tell-all interviews, memoirs, and the darkly comedic novel Tampa after being arrested for abusing a 14-year-old male student in 2004.

Even now, every time an arrest makes headlines, the comments sections of the articles or YouTube videos fill up with comments from men, extolling the woman’s looks, or joking about wishing they had been transgressed upon. (As “Hot for Teacher” puts it: “I think of all the education that I missed / But then my homework was never quite like this.”)

The fact that the actual teen students in these real-life cases are almost always minors, and/or shielded from media scrutiny as sex crime victims, renders them almost invisible specters in their own stories.

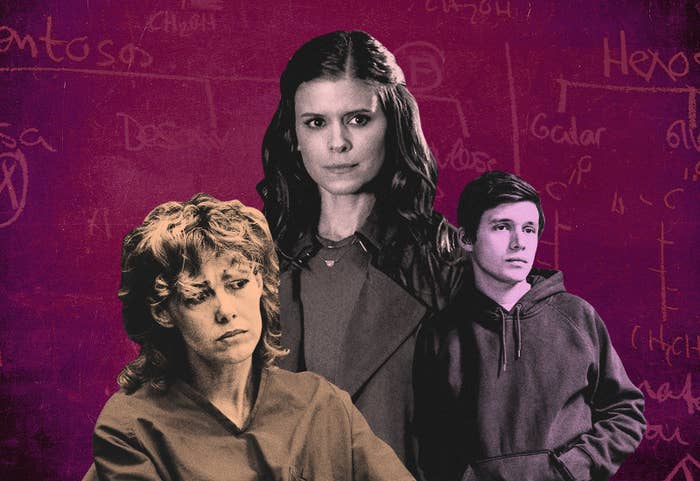

That’s not the case in the new Hulu FX series A Teacher, which repackages a story plucked from the sensational headlines and drops it into the muted palette and tenor of prestige TV drama. Based on Hannah Fidell’s 2013 film of the same name, the series, set in suburban Texas, focuses on a young teacher named Claire Wilson (played by Kate Mara) and her student Eric Walker (played by Love, Simon’s Nick Robinson).

And despite its title, the show doesn’t limit itself to the perspective of the woman teacher. Split across 10 episodes, written and directed not just by Fidell but by a group of writers and directors, the show depicts the messy aftermath of an abusive relationship, foregrounding the student’s point of view. The series ultimately provides a nuanced deconstruction of a storyline that has become a cultural phenomenon — but mostly for the wrong reasons.

Teacher-student scandals mostly go viral as tabloid news stories, but there have also been attempts to grapple with the deeper meaning of these cases. Novels like Zoë Heller’s 2003 Notes on a Scandal and Alissa Nutting’s 2004 Tampa both attempted to give more dimension to the stories as a commentary on gender, though they mostly stay with the perspective of the teachers involved.

Tampa, as Nutting pointed out, was meant to be a dark comedy about the idea of a woman sexual predator. The protagonist, Celeste, ends up getting involved with two students and is exposed after the students fight each other, culminating with a (ridiculous) scene of her running behind one of them with a knife down a suburban street. Notes on a Scandal, which became a movie starring Cate Blanchett as the teacher, is about the perspective of the older friend (Judi Dench) who exposes her sexual relationship with the student.

Neither story is meant to focus on the kind of questions about agency and trauma that A Teacher foregrounds by giving equal space to the student’s perspective. The series begins as the school year starts, and we meet Claire and Eric: She’s recently moved to a new town with her husband and feels lonely; he’s a high school senior and responsibility-laden son of a single mom. Eric is more thoughtful than his privileged, stereotypically boyish friends, and it’s precisely that sensitivity that makes him susceptible to Claire’s advances.

There aren’t really any ready-made narratives for thinking about the ways white women perpetrate violence and are not held accountable.

The series’ writing makes viewers stay aware of the imbalance in their power dynamics, but also keeps the relationship plausible enough. (That the real-life actor playing Eric is 25 helps viewers not initially read the interactions as overt grooming.)

Their relationship begins when Eric needs tutoring for the SATs and works with Claire. And a pivotal moment comes when Eric gets caught illegally drinking at a party and fears that the mark on his record will impact his ability to get a scholarship. He drops Claire’s name to the arresting cop, who happens to be her brother. In return, she asks her brother not to charge him so it won’t affect his entry to the University of Texas, and he agrees.

Eric is never flattened into the horny student of “Hot for Teacher” fantasies. Instead, we see him getting pulled into the relationship through a combination of genuine need for scholarly mentorship and, later, misguided yet earnest romantic chivalry.

Claire becomes controlling, as she ups the ante on her demands, seemingly getting off on her power over Eric. She sends him nudes from a bathroom and asks to meet him right at that moment, even though he’s babysitting. In turn, he begins lying to his mom in order to spend time with Claire.

It’s telling that Claire is so insulated by the benefit of doubt from the world surrounding her, including Eric’s mother, that despite the reckless behavior, she never gets caught. It’s only when she lets her guard down while drinking with a fellow teacher, and confides that she’s having sex with Eric, that it all crumbles down.

The media’s coverage of the #MeToo movement has largely centered on straight white women’s trauma and holding men and the institutions that enable them accountable. That coverage has widely resonated because it builds on the massive social capital that white women’s suffering holds in contemporary culture.

In contrast, there aren’t really any ready-made narratives for thinking about the ways white women perpetrate violence and are not held accountable. (This is partly what propels the popularity of Karen memes.)

A Teacher doesn’t explicitly foreground race, but it is smart about Claire’s privilege as a white, middle-class woman. She has no issue, for instance, using her connection with the police to help Eric and draw him in more. And the series emphasizes the ways she attempts to grapple — often cluelessly — with her culpability.

Claire has to wear a monitoring ankle bracelet, and she is defensive about being seen as a sexual predator, implying that Eric wasn’t really a child. But neither the people she seeks a sympathetic ear from nor the series believe that lessens her abuse of power or the trauma Eric experienced.

For instance, as Eric tries to move on in college, the scandal follows him as his fraternity brothers project a sexual persona onto him that makes him feel even more alienated from himself. He is forced to present his trauma as macho sexual conquest for their consumption. He struggles, too, with feelings of guilt, blaming himself for Claire’s arrest, and his grades drop precipitously.

The weight on Eric is emphasized when the series flashes forward further. Claire has remarried and has her own children. In contrast, Eric has a job as a camp counselor, presumably attempting to work out his own issues through helping other teens, but continues to be haunted by the relationship. When he returns home, the series hones in on his perspective even more as he reenters his previous life. Reencountering his younger brothers, one of whom is a senior with braces (played by an actual teen actor), helps Eric (and the viewers) confront the uncomfortable nature of the abuse.

A Teacher’s depiction of Eric’s innocence brings to mind the media coverage of one of the most famous teacher scandals. Not incidentally, it involved a student who wasn’t white: Vili Fualaau, the 12-year-old pupil of then-34-year-old Seattle teacher Mary Kay Letourneau.

Letourneau, recently back in the headlines because of her death from cancer, became one of the most infamous women in America in the late ’90s and early aughts. Her abusive relationship with sixth-grader Fualaau was depicted at the time as a kind of misunderstood love story. Or as a French book about the story put it: Only One Crime: Love.

In order to be a “love story,” it also had to be a story about Fualaau’s supposed sexual agency. In the media, Fualaau was basically treated as a teen from the “wrong side of the tracks.” There were rumblings at the time, as Gregg Olsen wrote in his true crime book about the case, If Loving You Is Wrong, that Samoan boys were somehow less innocent than white boys — and that Fualaau had pursued Letourneau.

After she had Fualaau’s baby, Letourneau’s white motherhood became her protective mantle. She was featured in a 1998 People magazine cover, posing with the baby, staring sadly at the camera like a mater dolorosa. In 2000, she was the subject of a Lifetime-style TV movie emphasizing her normality: All-American Girl: The Mary Kay Letourneau Story. Their 2005 wedding was eventually broadcast on TV.

Though the couple was splashed all over the media, Fualaau’s perspective was totally lost in the story. Even years later, Fualaau was still blaming himself for the trauma he endured. “I think, What would my life have been like if I had never made a move on Mary?” he wondered in a People magazine interview a year after the wedding. “What if I had kept it as a crush and left it at that?”

In a rare recent interview before her death, Letourneau kept making Fualauu say “I pursued you,” even as interviewers tried to clarify the troubling power imbalance. “Who was the boss?” she asked him. “Who was the boss back then?” “This is weird,” Fualaau responded, backed into a corner. The episode illustrated the very particular ways white women’s violence is overlooked.

That she was still trying to insist on a 12-year-old’s agency — and that he was still blaming himself for what happened to him — is a testament to the cultural logic that insists that sexual abuse is about sex and desire, and not about power and trauma.

In an interview with Dr. Oz after Letourneau’s death, Fualaau was still grappling with the aftermath of their relationship. As he was now in his thirties, he realized he could never be attracted to a teenager, and it made him question Letourneau’s actions. But, he ultimately concluded, Letourneau wasn’t some habitual predator of minors, so maybe morality can’t be “legislated.”

The comments echoed a broader cultural understanding of power and sexual abuse. It’s as if someone who commits an abusive act is either a monster, or else the abuse was a misunderstood love affair (at least when a white woman is at the story’s center). At the same time, his invocation of legislation arguably raises questions about carceral solutions that can themselves be traumatizing.

A Teacher similarly depicts Eric’s feelings of culpability around the way the case was turned into a judicial matter. It also asks, through the reaction to Claire, whether simply punitively ostracizing those deemed “sexual predators” is an ethical solution.

The show admirably subverts the “hot for teacher” trope, removing it from the realm of cis-hetero fantasy. By focusing not on some specter of the monstrous predator but on the subtle workings of power and the consequences of trauma on the minor, it makes space for the vulnerabilities of teen boys. In a final scene where Claire asks Eric to lunch, it’s clear she still doesn’t understand the trauma she caused and her responsibility for it. She’s always a Google search away from discovery, she tells him. He has to live with it forever, he replies.

“Where would I be and where would she be?” Fualauu wondered in one interview, imagining a trajectory without his traumatic past. “What would life be like?” ●