After Jeffrey Epstein’s highly publicized 2019 arrest for sex trafficking, questions lingered about how his pattern of abuse had remained hidden in plain sight. The friendships with rich and powerful men — Bill Clinton, Donald Trump, and Prince Andrew — came under renewed scrutiny; headlines trumpeted alleged travels in the so-called Lolita Express, the airplane reportedly ferrying underage girls to Epstein’s private island.

Epstein’s subsequent death by suicide in prison that summer — under questionable circumstances — only added to the mystery of what he knew. Attention shifted to his less well-known partner in romance and alleged crime, Ghislaine Maxwell, who now held the secrets.

Amid the increased scrutiny, old pictures trickled out of the woman described as a British socialite, hobnobbing next to Naomi Campbell and Martha Stewart, at Chelsea Clinton’s wedding. When she was spotted later that summer at an In-N-Out Burger the paparazzi image of her almost-amused expression became a memorable snapshot of her downfall — and shamelessness. It took a year for her to be arrested at her hideout in New Hampshire, and she now awaits trial for charges ranging from perjury to trafficking, set for November.

After the reams of coverage on this case — including an Epstein documentary on Netflix — it seems there is nothing new to uncover. But the new three-part Peacock documentary Epstein’s Shadow places the whole sordid case in context through its focus on Maxwell’s life and trajectory.

Directed by Barbara Shearer, the documentary draws on interviews with former friends, unsealed court depositions, and authorities to move beyond the media fascination with the supposed incongruity of the daughter of privilege and sex trafficker. It shows instead how Maxwell’s class background is precisely what habituated her to the kind of ruthlessness that led to her alleged criminal behavior.

Epstein’s Shadow focuses on Maxwell’s life story as the key to the case, but less to explore the psychology of motivations and more as a way to contextualize the values and class milieu that normalized violent entitlement.

Her father, Robert Maxwell, was a self-made British publishing magnate — he owned a conglomerate that included the Daily Mirror — who had worked his way up from a shtetl in Czechoslovakia. His biographer calls him a “domineering ogre and tyrant,” both in his family and corporate life. He used his newspaper as a blackmail tool and his publishing company was investigated for fraudulent accounting. According to the documentary, he treated his family like a corporation, expecting the kids to be on constant guard, as if they were employees.

Anna Pasternak, a former friend of Maxwell’s who has made something of a career charismatically denouncing her disgraced social peers, like Martha Stewart, describes Maxwell, the baby of the family, as “a daddy’s girl with a difference, that he could turn.” She also explains how Maxwell “learned early to read a powerful man’s moods.”

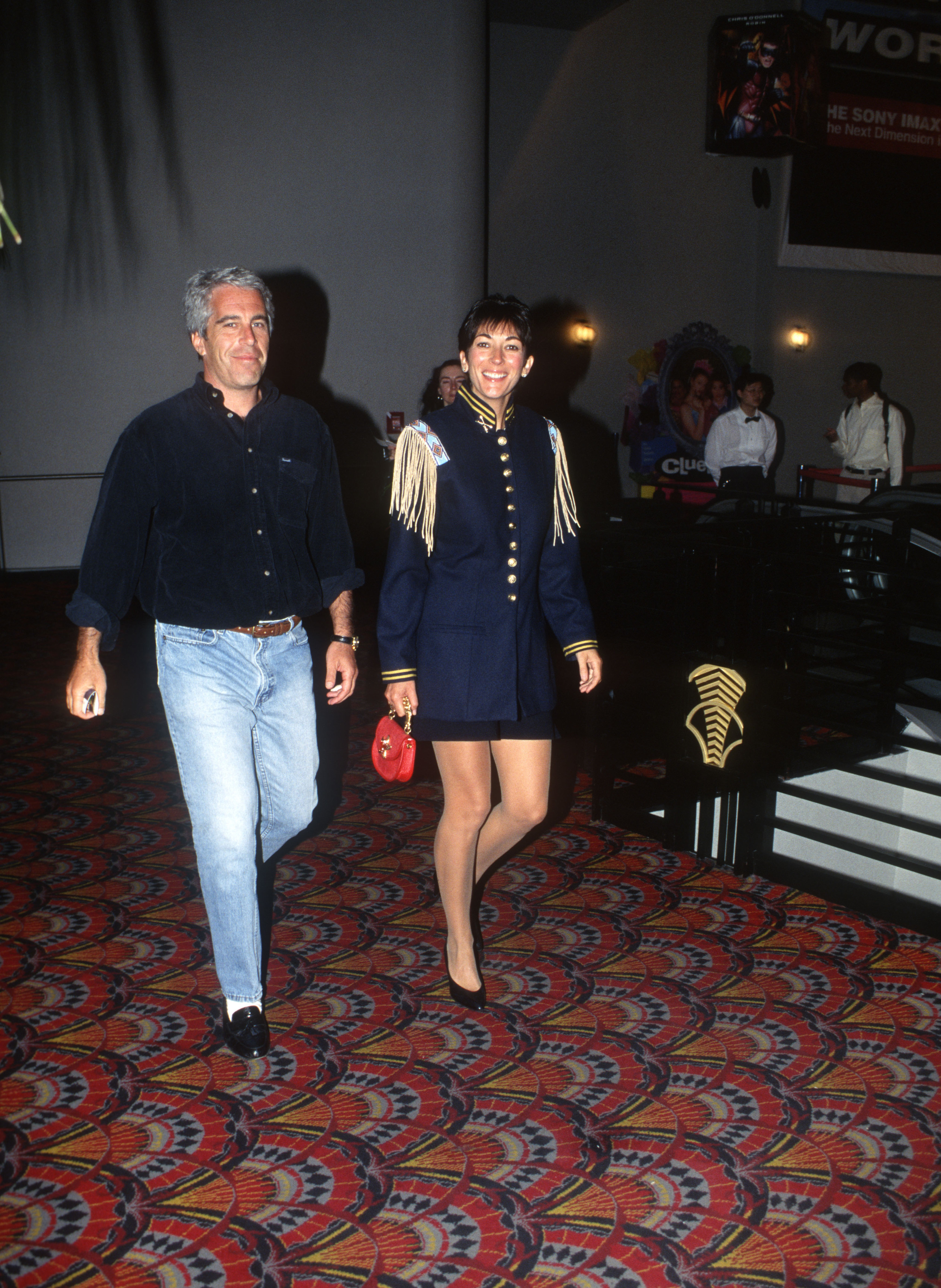

Maxwell went to Oxford, but her biggest achievement was moving in influential circles, going to club openings, and becoming something of a figurehead for her father’s company. They were like an avant la lettre Donald and Ivanka Trump duo; Maxwell preferred having his daughter on his arm at events, as a kind of first lady, instead of his wife. He bought her a football club, turning her into the first “lady director” of one. His yacht was called the Lady Ghislaine.

In the early ’90s, she went transatlantic, becoming a frequent party-goer in New York City after her father bought the Daily News. But it all came to an end after Robert Maxwell died under questionable circumstances, his nude body found floating in the ocean miles away from his yacht. It turned out he had siphoned over $1 billion from his employees’ pension funds, and the family fell into social disgrace. The documentary cites reports at the time that Ghislaine Maxwell had gone to the boat soon after his death to shred documents. Then Epstein came into the picture.

The documentary never loses sight of the fact that the Epstein case was, as a victim’s attorney points out, a sexual Ponzi scheme. And though it didn’t involve ritual brandings, the similarities between the Epstein trafficking case and the so-called NXIVM “cult” are striking.

In particular, both featured a similar dynamic between the orchestrator of the sexual abuse — Keith Raniere in NXIVM, Epstein here — and the woman lieutenant helping to carry out the recruiting and normalizing the abuse — Allison Mack for NXIVM and allegedly Maxwell in the Epstein case.

If NXIVM operated through warped self-help philosophies, in the Epstein case, the institution of ultra-rich white heterosexuality was the system through which Epstein and Maxwell came together, and through which they perpetrated — and covered up — their alleged abuse.

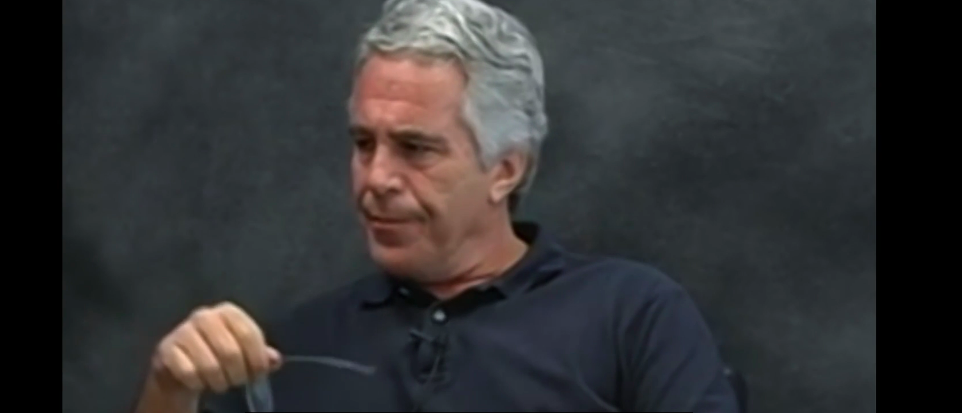

The documentary chronicles how Epstein, a high school math nerd, hustled his way from a two-bedroom home in Coney Island to Bear Stearns, which he left under questionable circumstances. Still, he ended up as a money manager, including for the billionaire owner of Victoria’s Secret, who later accused him of stealing tens of millions of dollars.

Epstein helped Maxwell live beyond the means of her £80,000-a-year trust fund; she provided him with a patina of glamour and, in terms of the sexual recruitment, a front, as the “respectable wife” (they were not married).

Maria Farmer, an artist who was hired as an assistant and who said Maxwell and Epstein sexually assaulted her, says in the documentary that she trusted Maxwell because she seemed to be a philanthropist, and they appeared to be a married couple.

She recalls that Maxwell would scout for young girls in Central Park in a limo. When they would leave the house crying, Maxwell would tell Farmer they had just lost an audition for Victoria’s Secret. Maxwell also recruited girls in Palm Beach, where the couple vacationed, making sure they were from the “wrong side of the tracks” (as one columnist talking head puts it), and would offer them massage jobs that would allegedly turn into sexual assault.

“They’re nothing, these girls,” the documentary quotes Maxwell as saying of the victims, alluding to the class politics that allowed her and Epstein to operate undetected. A recurring theme of Epstein’s Shadow is the lack of action either by authorities, like the FBI, or, later, by the upper echelons of national law enforcement, like attorneys general. Farmer contacted the NYPD and FBI in 1996 about the sexual abuse and nothing was done.

Florida authorities started investigating again in the 2000s after the mother of one of the victims found $300 on her after her daughter had visited the mansion. Authorities found a cache of pictures and videos confirming the abuse. By 2007, Epstein was given a deal for pleading guilty to state charges of “soliciting prostitution” but avoided federal charges.

He was sentenced to just 13 months at the county jail, which included a work release portion allowing him to be in his Palm Beach office. Even the deal’s language of “soliciting prostitution” was a further stigmatization of the victims who were not sex workers, as a prosecutor points out in the documentary. Further, the deal involved complete immunity for Maxwell.

Maxwell started distancing herself from Epstein and tried to reinvent herself as a philanthropist saving the oceans with the TerraMar Project, supposedly an environmental nonprofit. (The footage of her explaining its mission comes off as platitudinously basic.) It was only after survivor Virginia Giuffre went public in 2015 that Maxwell disappeared from the social scene altogether the following year. She was not photographed in public again until the 2019 In-N-Out picture.

She had assumed that Epstein would beat the charges. According to the documentary, Maxwell was surprised to be investigated and furious about being deposed, reportedly knocking a lawyer’s laptop off a desk and pounding the table. (Like her father.) Maxwell has since attempted to discredit the accusers and pleaded not guilty at her court appearance. She is now in prison facing charges, including trafficking a 14-year old.

Toward the end, the documentary raises questions about whether Epstein was a Mossad agent (he had been involved in international arms dealing) and if that could be connected to his death or the influences that allowed him to operate undetected. (A former CIA operative points out that it’s not necessarily the theory that he was murdered that should encourage suspicion, but more that he was allowed to kill himself under the prison’s watch.) There’s similar speculation about Maxwell, because her father also had ties to international spying.

But the portrait of unchecked privilege — and authorities ignoring the abuse of working- or middle-class girls — almost makes that kind of speculation about bigger conspiracies seem unnecessary.

“I don’t feel smaller or lesser than what I was before,” Maxwell said in an interview after the exposure of her father’s thievery in the ’90s. “I’m me.” One gets the sense that not much has changed. ●