George Michael’s untimely death in December 2016 — just months after the world had mourned David Bowie and Prince — felt like a final blow to the legacy of the gender-bending men of ’80s MTV. For a brief moment, the 53-year old British star had been their equal: a pop supernova mentioned alongside Michael Jackson and Madonna.

Hip-wiggling onto the music scene as one-half of the ’80s teen pop duo Wham!, he became a global superstar thanks to the 1987 album Faith. His videogenic, queer-flirting imagery — defined by studded leather jackets that clung to his bare chest —made him a global superstar. Yet he publicly denied being gay. And at the zenith of his fame, he started retreating from his celebrity. He refused to appear in the promotional imagery or videos for his follow-up album. And long before Taylor Swift v. Scooter Braun, he got embroiled in an industry dispute over his contract.

After a 1998 arrest for “lewd conduct” in a Beverly Hills public bathroom, he began a spiral into drugs and drunk-driving incidents. Soon, he was less famous for his music than for his tabloid antics. “I think, in a strange way,” he reflected in the press before his death, “I’ve spent much of the last 15 or 20 years trying to derail my own career.”

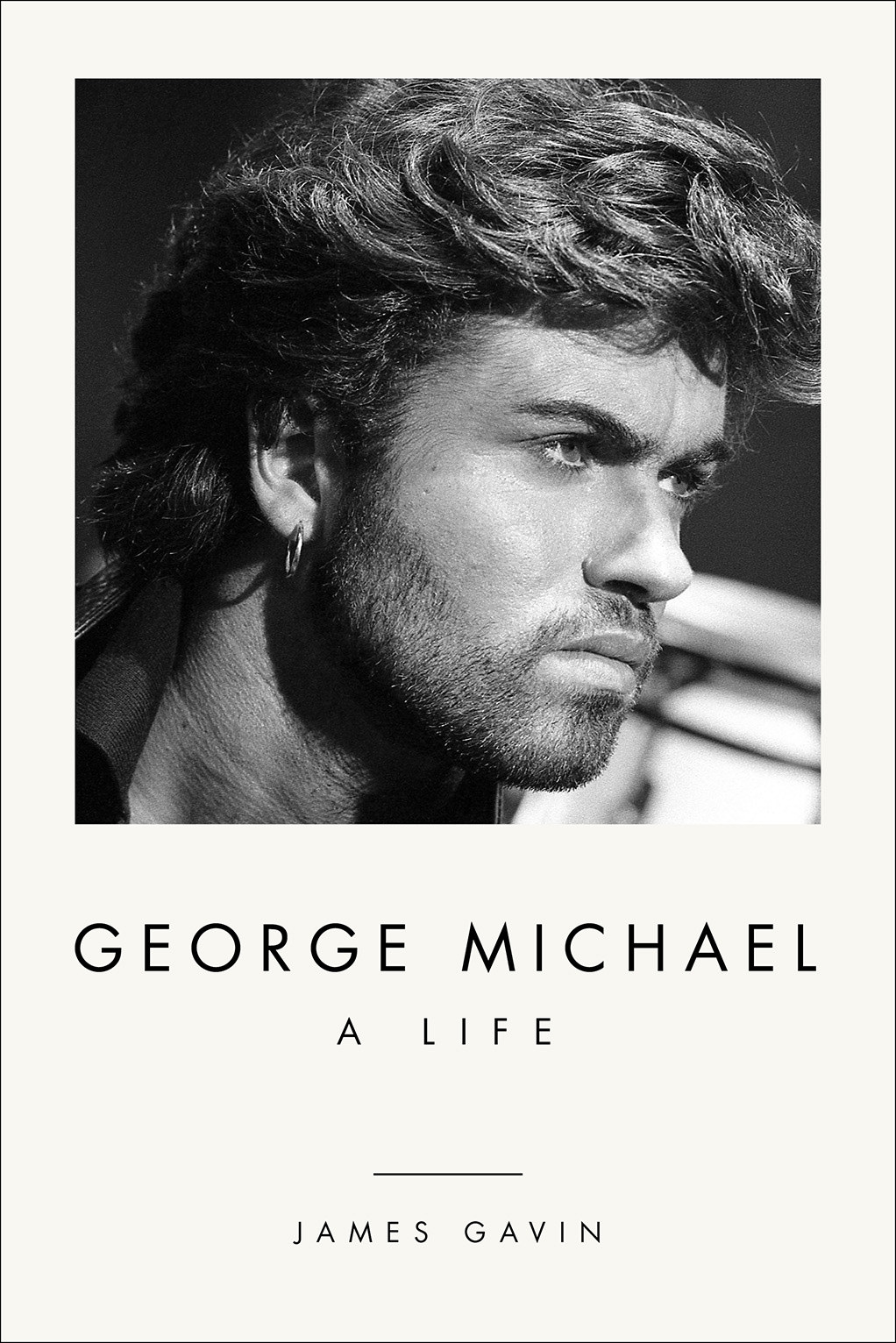

Now James Gavin, a queer music writer who has penned books on Peggy Lee and Lena Horne, tries to make sense of what he calls one “of the industry’s most privileged yet tortured men” in the new biography George Michael: A Life. The book isn't a tabloid tell-all with unexpected reporting or massive surprises. But Gavin does get everyone from billionaire David Geffen to Michael’s friends and colleagues on record, and he paints a convincing portrait of a gay man struggling with unresolved trauma in the narrow confines of a straight world and industry.

Before he transformed into George Michael, he was shy, femme Georgios Kyriacos Panayiotou, born into a conservative Greek Orthodox family in England.

As a queer teen, Gavin writes, Michael was rejected by his family early on. “I think George’s father was a homophobic bastard who caused George a lot of pain,” James Sullivan, a gay exchange student from Brooklyn who got close to Michael in his teen years, tells Gavin. “He found happiness in music and in [bandmate Andrew] Ridgeley’s acceptance of him.”

Michael met the other half of Wham!, Andrew Ridgeley, in middle school. In a deeply anti-gay era, Michael and Ridgeley, who was straight, became best friends and bonded over being “soul boys,” a subculture of white kids into soul music. They channeled their love of new wave, ska, and hip-hop into a band, The Executive, and then, spearheaded by Michael, wrote demos that got them a record contract for Wham! and their first big break on Top of the Pops.

In deeply ’80s songs and neon-bright videos, the duo gave off a kind of polymorphously sexual vibe. They wore speedos in the video for “Club Tropicana” and tiny shorts in the one for “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go.”

They shot to number one on the charts and sold out concerts worldwide. They’d take out shuttlecocks from their shorts and throw them out to screaming girls driven wild by their teen-idol hip-thrusting. They were always hetero’d up, though, surrounded by women models and backup singers.

The biography emphasizes how Michael heterosexualized the imagery by dating or seeming to date women in his orbit. “He was up against so many things,” Judy Wieder, a friend and later editor of gay magazine The Advocate, tells Gavin. “He didn’t like the feeling of being dishonest with his audience. He was really lonely, and he’d been trying to explore being straight to be sure that he couldn’t make life easier for himself.”

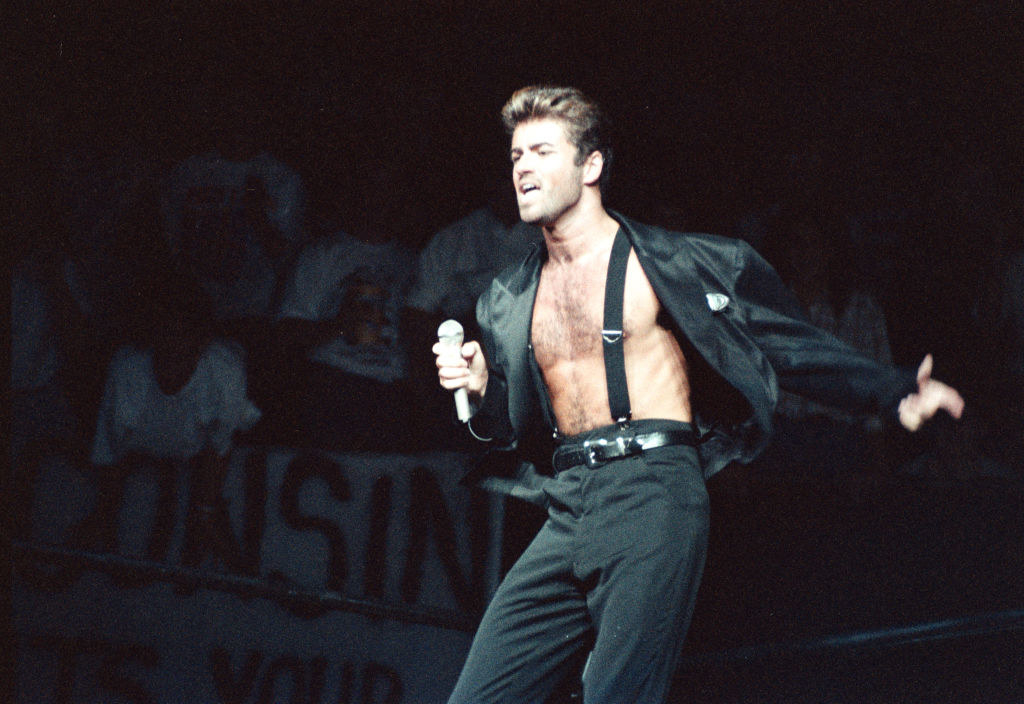

Faith, Michael’s solo effort and attempt to catch up to Prince, launched him as a sexual, macho, leather-jacketed sex symbol for women. In the funky title bop, he shook his ass in tight jeans. But he also showed his range in songs like “Father Figure,” which combined gospel intimacy with gay daddy energy. Faith won Album of the Year at the Grammy Awards.

As questions intensified about his sexuality, he denied rumors outright. “No, I’m not,” he replied when asked point-blank by 60 Minutes Australia whether he was gay in 1988. “But the main thing I’d like to express is I don’t think it’s anybody’s business.”

There were reasons for the reticence. Gavin brings the hostile culture of the time to life: Tabloid editor Piers Morgan ran an article headlined “The Poofs of Pop.” Straight journalists felt entitled to ask Michael questions like “Have you had an AIDS test?” Record company president Walter Yetnikoff threw around expressions like “Don’t be such a fag.”

In fact, Michael’s problems with the label started because of anti-gay comments made by a music industry figure just as Michael seemed to be shaping his image on his own terms and coming into himself.

For his 1990 album, Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1., Michael decided he wouldn’t be in the music videos. Instead, he enlisted supermodels like Cindy Crawford and Naomi Campbell to lip-synch his song “Freedom! 90,” alongside iconic visuals where the jacket and guitar that symbolized his earlier incarnation suddenly combust.

Manager Rob Kahane tells Gavin that US label head Donny Lenner asked him to demand more promotion or a music video from “that faggot client of yours.”

By 1991 Michael was growing artistically and personally, and he fell in love for the first time with Brazilian fan Anselmo Feleppa.

"I was happier than I’ve ever been in my entire life. Fame, money, all the things you know. Everything else just kind of paled by comparison,” he told Attitude years later. "To finally at 27 years old, wak[e] ... up in bed with someone who loves you. ... Anselmo was absolutely that.”

But he wasn’t out — either to the public or his family — when their relationship started. And Feleppa contracted HIV just six months later. Michael couldn’t accompany him to treatments for fear of being outed. “I think George was miserable his whole life,” Sullivan tells Gavin. “He was confused and scared — scared of rumors, scared of a lot of things.”

“He was so fearful of anybody finding out about anything,” Bret Witke tells Gavin. “I think his whole life was based on that fear, and I think he never reconciled it. There was a lot of anger in him.”

In despair soon after his boyfriend’s death in 1993, Michael sued the record company, egged on by his manager, over the overly restrictive contract. He lost the battle, and by the time he released new music in 1996, a lifetime had passed in pop music years.

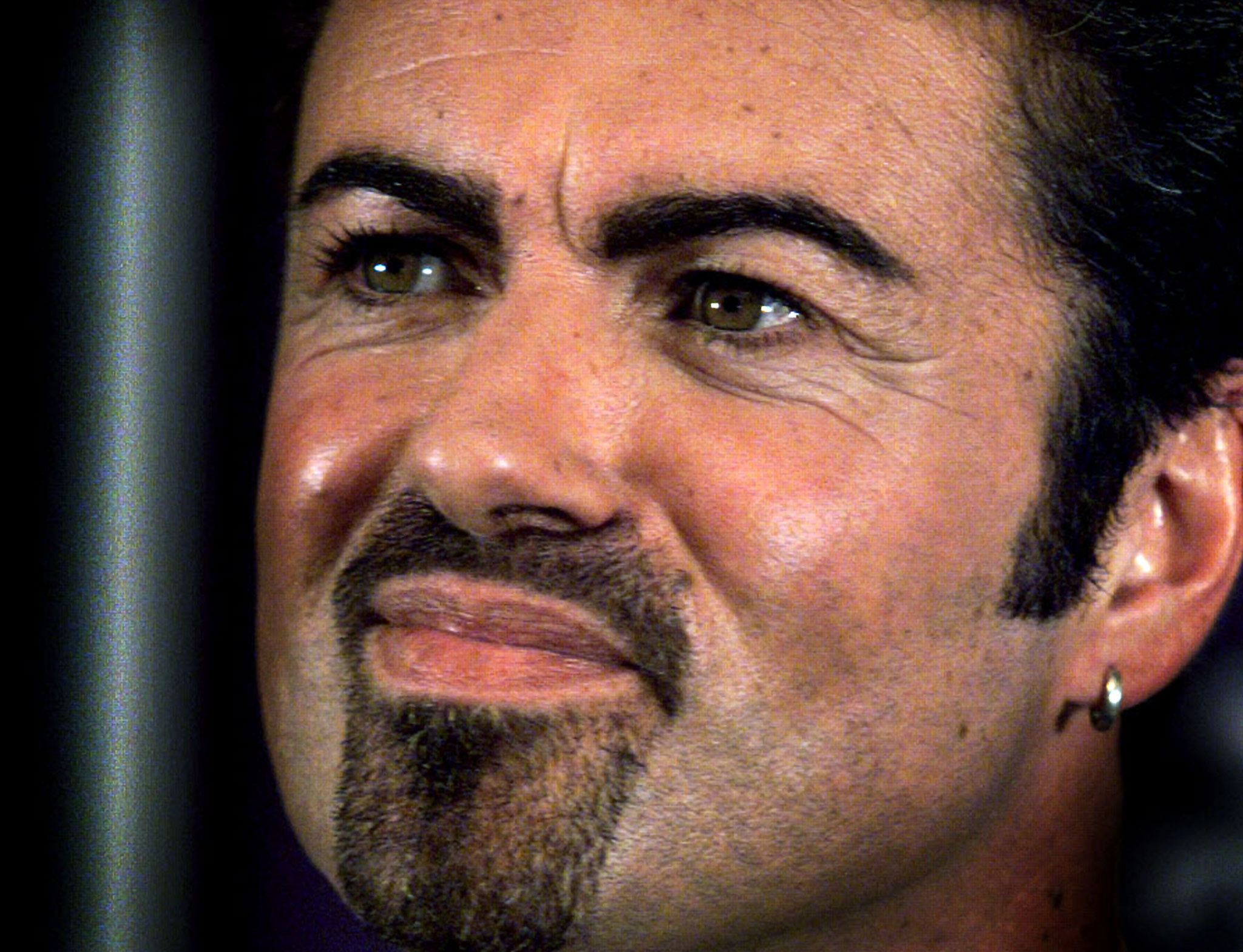

With the release of the single “Fastlove,” a dance song about ephemeral love that Adele later sang at his Grammy tribute, Michael debuted the goateed look of his later years, what Gavin describes as “half clone half pop star.” The album, Older, went to number one in the UK. But Michael became something of a niche club act in the US.

In 1998, while he was cruising for sex, police entrapped him in a Beverly Hills bathroom, and he was outed to the world. The arrest caused a scandal that made more news than any of his music. He released a campy dance single “Outside,” and played a cop in the video, making light of the public outcry. It was time, he said, for the public to accept gay men as sexual, and not some “tea and biscuits” version of themselves.

Yet even though he was publicly out, he didn’t seem to be in less pain. The biography paints a picture of a millionaire enabled by self-interested boyfriends, family, and hangers-on.

One friend recalls Michael’s father’s reaction to the outing as: “Don’t worry about it, son. I understand… And oh, by the way, I’ve just seen a new horse. It’s only half a million, George, can I buy it?” Michael started losing himself in drugs: first pot and later the drug G.

“His family didn’t really say anything” about the drugs, music producer Niall Flynn admits. “People like me were depending on him for our salaries... When you’re in that situation it feels a bit difficult to stand up and say, ‘I don’t agree with what you’re doing.’”

It’s striking how much his unprocessed trauma showed up in his music of this period. In 2004’s album Patience, he included the song “My Mother Had a Brother,” about his uncle who was rumored to be gay and killed himself. Another song he wrote, “The Fag and White Minstrel Show,” was a letter from a dad to an estranged gay son.

He ultimately decided against releasing it. He also canceled a planned memoir after he had signed a multimillion-dollar contract to tell all. But, throughout the aughts, his private life and health troubles were becoming a tabloid drama factory outside his control.

He was involved in a car crash while intoxicated and sentenced to eight weeks in jail in 2010. The following year, he caught pneumonia. His keyboardist Chris Cameron tells Gavin the pop star seemed reconciled to death. “It was almost like, ‘Mum is there, Anselmo is there — this is where I’m going to have to be.’”

By 2015, he went to a rehab facility in Switzerland that included a specialist in depression among gay people related to experiences in their childhoods. The following year, he was dead.

The official cause of Michael’s death on Dec. 25, 2016, was cardiac arrest. But it remains a mystery what exactly caused the heart failure and exactly when it happened. In the book, friends speculate about an overdose, hinting that his death around Christmas was related to his mother’s death during that season in 1997. And Gavin lays out how Michael’s family and his boyfriend, Fadi Fawaz, gave conflicting statements about times and causes of death.

George Michael: A Life mostly does a good job of paying respectful attention to Michael’s biography and the music that he took so seriously. But, toward the end, Gavin relies on quotes from music critics to frame Michael as an ’80s niche act who didn’t quite live up to the best of the era. The book also includes friends suggesting his reaction to the lack of success in the US after coming out was paranoid or self-pitying. David Geffen is quoted saying that Michael “was attached to being a victim.”

But the music industry was stacked against artists in many ways. (In the documentary George Michael: A Different Story, Mariah Carey says there was merit to his Sony lawsuit and he should have won.) Pop music was systematically anti-gay. And music history tends to underplay the impact of queer artists.

In a way, framing him solely in the ’80s context and comparing him to straight stars overlooks how he presciently played out the kind of queer-specific reinventions later enacted by Troye Sivan in a more open era.

The sly brilliance of Michael’s ability to make space for himself within a culture that tried to erase him was art unto itself. “Gotta have some faith in the sound,” he sang in the autobiographical song “Freedom! 90.” “It’s the one good thing that I’ve got.” It couldn’t save him, but his music lives on forever. ●

Correction:

The album Faith came out in 1987. A previous version of this story misstated the date.