In January 1989, 29-year-old Eileen Franklin-Lipsker was playing at home with her daughter when her mind was suddenly flooded with violent memories, she later recalled. In these memories, she said she saw her father, George Franklin, molesting and attacking her childhood best friend, Susan Nason, who had been murdered 20 years before.

She and her older sister, Janice, had also accused their father of childhood sexual abuse. Amid the family drama, Franklin-Lipsker’s husband eventually called the police about her memory, unleashing an investigation that led to Franklin’s trial.

The trial became a flashpoint in the ’90s media obsession with “recovered” or “repressed” memories. They had become a staple of talk shows, and incest and sexual abuse in the family were also becoming national talking points. Celebrities like Roseanne Barr came forward with claims of repressed parental sexual abuse.

Thanks to her role in her father’s trial, Franklin-Lipsker became something of a figurehead of this phenomenon. After (spoiler alert) her father was convicted, she was interviewed on morning talk shows, people wrote books about her, and she was even played by Shelley Long in a TV movie. But her father’s murder conviction was eventually overturned, and questions arose about her memories of the murder.

The new four-episode Showtime docuseries Buried is a compelling retelling of Franklin-Lipsker’s story and a rare true crime production that attempts to mine larger cultural stakes, revisiting the ’90s wars over trauma and abuse that the story supposedly exemplified. The series adheres closely to the intricacies of Franklin-Lipsker’s story and is most successful when it recasts her narrative as one about sexual abuse and family trauma. But it’s ultimately muddled in elucidating the case’s legal and cultural impacts.

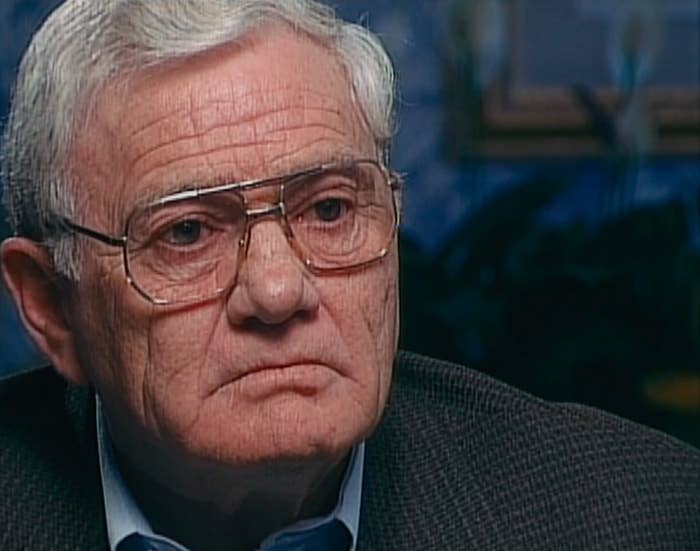

Though it starts with the mystery of 8-year-old Susan Nason’s disappearance and murder in Foster City, California, Buried mostly focuses on Franklin-Lipsker’s story and the Franklins overall. Neighbors recall them as a normal family, with a firefighter father and a devoted mom. But despite this facade of suburban calm, the Franklin children eventually said their father subjected them to constant physical and sexual abuse.

Following Franklin-Lipsker’s accusation about Nason’s murder, police uncovered sexual material involving minors in her father’s apartment, and when prosecutors interviewed former girlfriends, one recalled that Franklin had asked if he could have sex with her daughter. Another former girlfriend of Franklin’s claimed she’d never recognized any “abnormal” behaviors in him, but then casually told a prosecutor: “Oh, I broke up with him after he told me he’d had sex with his daughter.”

When the Nason murder case went to court in 1989, it became a media sensation. Franklin-Lipsker’s memories of her father’s attack on Nason were a major part of the prosecution’s case. At the trial, the defense questioned whether these memories — of her father assaulting Nason in their van and attacking her with a rock — had been recovered through hypnosis. (Hypnosis, often seen as some kind of truth serum, can potentially influence the way people remember things; testimony that emerged from hypnosis was inadmissible under California law.) Franklin-Lipsker said they weren’t.

In 1990, Franklin was convicted, partly because of the power of his daughter’s testimony, as jurors admitted. The conviction was seen as a vindication of recovered memories, and Franklin-Lipsker started to see herself as a media activist for victims of sexual abuse. According to the series, the case helped extend the statute of limitations on sexual abuse claims.

The problem with the way the Franklin story was covered — and in many ways, the documentary reproduces this issue — is that the media and the lawyers turned a complex story of family abuse into a referendum on a then-emerging debate about trauma and memory.

The prosecution and experts, like Lenore Terr, an expert on childhood trauma, claimed that given the ways trauma can affect memory, it was possible for a witness to completely repress a horrifying event. The defense and Elizabeth Loftus, an expert on memory but not trauma, claimed that wasn’t how memory works. The documentary frames itself as an examination of these two positions, but it simply rehashes them without pointing to the political and cultural stakes involved — for instance, in Loftus’s posture. (She ended up testifying for the defenses of Michael Jackson, Harvey Weinstein, and Ted Bundy, which is not mentioned in the series but speaks to the broader politics of her skepticism about trauma and memory.)

Franklin was eventually released from prison, but for legal reasons that had little to do with the specific questions about repressed memories. As others have pointed out, the reasoning related to a technicality about violations of his right not to self-incriminate and his right to counsel. This is not entirely clear in Buried.

Ultimately, prosecutors decided not to pursue another trial because Franklin-Lipsker and her sister fell out over a money loan, and her sister, Janice, testified that Franklin-Lipsker committed perjury in claiming the memories had not emerged through hypnosis. (This claim was never proven, though the documentary includes convincing evidence that hypnosis was involved.)

Buried lays out the tangled mess that followed as Franklin-Lipsker and Janice accused each other of nefarious motives. Franklin-Lipsker’s mother withdrew her support of her daughter because she didn’t believe some of the claims about symptoms caused by her father’s sexual abuse; Franklin-Lipsker said she continued having nightmares and memories, and she later accused her father of committing other murders, at least one of which he was arguably cleared of by DNA evidence.

Recovered memories had a last gasp as a media phenomenon as purported examples became increasingly outlandish. Claims of recovered memories of satanic ritual abuse, sparked by the McMartin preschool case, were eventually debunked. Roseanne Barr eventually took back her claims. But the recovered memory furor was, in retrospect, less a cautionary story about memory and trauma, and more about overzealous prosecutors and therapeutic malpractice.

In the McMartin preschool case, for instance, prosecutorial overreach and therapeutic malpractice helped false allegations mushroom into years of legal machinations. Similarly, Franklin’s prosecutors chose to focus largely on one witness’ information to get a conviction. And there was an open question about whether hypnosis did confuse Franklin-Lipsker’s memories around the murder. Yet neither of these issues is really analyzed with a wider critical lens in Buried.

The docuseries also doesn’t introduce any contemporary psychological experts to speak to the evolving consensus on trauma and memory or trace how this issue played out in subsequent cases. Franklin-Lipsker herself chose not to participate in the documentary, so we don’t know what she now thinks about the controversy she unleashed, and there’s no new insight about how hypnosis might actually have affected her memories.

Ultimately, Buried is a compelling recounting of the story that makes the characters and their motivations come alive. It's clear why Franklin-Lipsker's story came to symbolize an inflection point in the memory wars, as the family’s complex disputes spilled into the legal and media worlds. The case was a perfect storm of people’s biggest fears about how criminal justice might handle new ideas about trauma and memory. But the series could have used more cultural context to tease out why that actually matters, and how the case stoked panic about false accusations. Instead, Buried is content with the same conclusions the media reached decades ago. ●