Early on in Sorry to Bother You, rapper Boots Riley’s film directorial debut, there’s a scene in which protagonist Cassius “Cash” Green (Lakeith Stanfield); his girlfriend, Detroit (Tessa Thompson); his best friend, Salvador (Jermaine Fowler); and a coworker, Squeeze (Steven Yeun), are traveling in his car. When a rainstorm strikes, Cash asks Detroit to start the windshield wipers — a task that requires her to pull a system of ropes and pulleys to move the wipers back and forth. Salvador complains that he’s never allowed to handle windshield duty, while Squeeze looks on, amused.

It's a moment that captures what the movie does best: intermingling the personal and the political with a dash of humor.

For those who are unfamiliar, Sorry to Bother You is about Cash, a black telemarketer who rises up the ranks at work after discovering and wielding his literal “white voice” (supplied by David Cross). When he gets promoted to the top tier of telemarketing, Cash learns that “power callers” specialize in selling weapons and cheap labor to global elites. Cash’s promotion also puts him at odds with Detroit and their coworkers, who have formed a union. Eventually, he meets a powerful, coked-up billionaire (Armie Hammer) who reveals his scheme to genetically engineer the perfect source of cheap labor — and he wants Cash’s help. Throughout the film, there are dense layers of references to pop culture, music, and politics. In a way, the movie is always “on,” as every scene and exchange aims to be political, funny, or both.

In that sense, the film is a noticeable extension of Riley’s signature style. Since the 1993 debut of his rap group, the Coup, Riley has been a consistent anti-capitalist voice within hip-hop. As an MC, Riley went beyond exhaustive soapboxing and corny conscious ballads. He also did a better job avoiding the misogynistic, anti-gay, and anti-Semitic pitfalls that mar Public Enemy and Ice Cube’s otherwise stellar early work. The Coup pulled it off by remaining true to their socialist politics, for sure, but Riley also grounded his views with humor, emotion, and impressive storytelling skills — all supported by funky, throwback beats that often were supplied by live musicians.

Sorry to Bother You marks a great moment in time to revisit the group’s back catalog. These days, more young people claim they reject capitalism, and they seem more open to socialism than older generations. This trend is perhaps best exemplified by the recent news that self-described Democratic Socialist Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, 28, defeated an establishment incumbent Democrat in the primary elections for her New York City district. The unionization plotline also feels relevant given the recent wave of teachers strikes that have garnered national headlines. The Coup’s music offers similar themes for listeners, a soundtrack for class warfare, and anti-imperialist efforts.

Additionally, the fact that a socialist rap group dropped a number of acclaimed, even classic, albums should be more than a footnote in hip-hop history or an entry in a listicle. Mainstream rappers like J. Cole and Kendrick Lamar continue to infuse politics into their work, so it’s clear that a broad audience can handle music with a message. Sorry to Bother You has earned a lot of acclaim already, boasting a 95% critics score on Rotten Tomatoes, and, after a promising limited release, it earned over $4 million the weekend it expanded to more theaters. This film is bound to resonate with people as it reaches more viewers. And I think the Coup’s back catalog will appeal to them too.

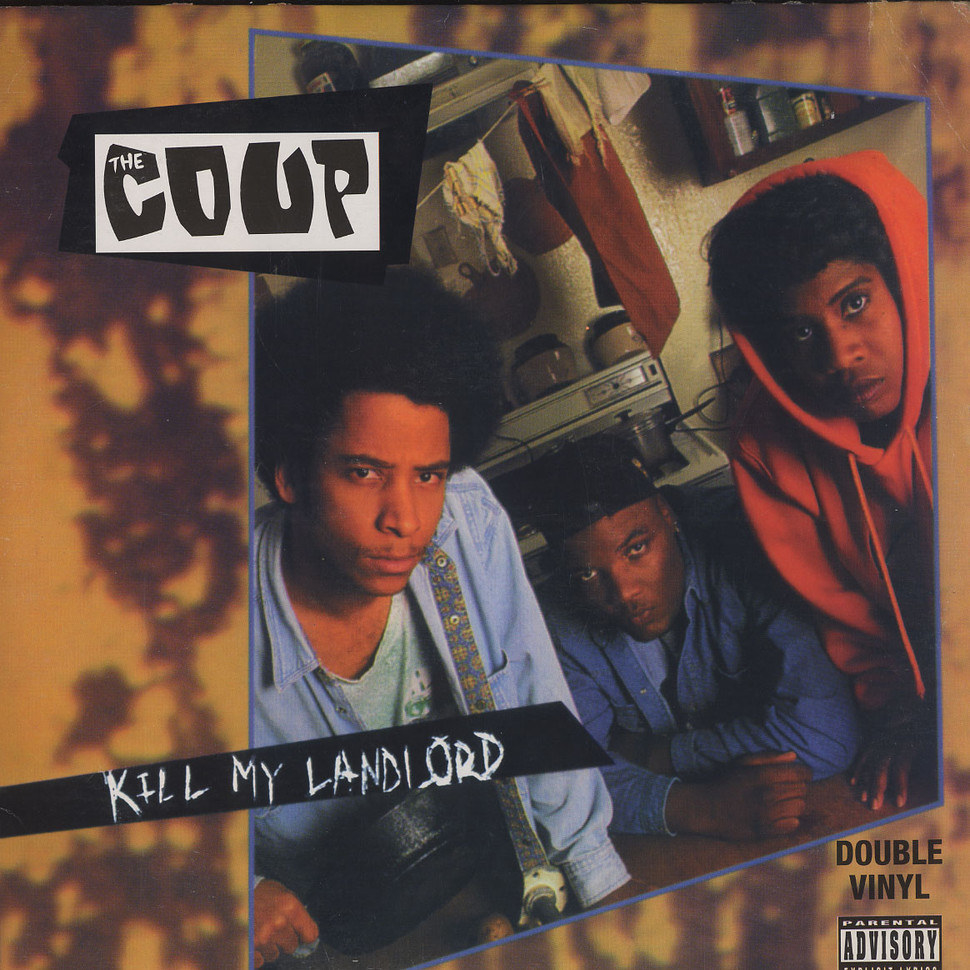

The Coup began as a trio comprising Riley, E-Roc, and the late Pam the Funkstress, who died in 2017 at 51. Only Riley remains in the group now. They released their debut album, Kill My Landlord, in 1993. Their lead single, “Not Yet Free,” connects the struggle of street life and its effect on one’s psyche — “And every day I pulls a front so nobody pulls my card / I got a mirror in my pocket and I practice lookin’ hard” — to how capitalism physically decimates marginalized communities — “Capitalism is like a spider, the web is getting tighter. … / It's like a noose, asphyxiation sets in.” Their two follow-ups, Genocide & Juice and Steal This Album!, have been called underground classics by outlets like the AV Club, OkayPlayer, and Pitchfork. As the former’s title suggests, the Coup mixed the West Coast funk-heavy sound with sharp political observations.

The group’s radical politics have, to no surprise, garnered controversy. The Coup’s third album, Party Music, made national news because of a controversial cover — one that suffered from very unfortunate timing due to its planned release date in September 2001. The picture, drafted months before 9/11, featured Riley and Pam detonating the World Trade Center towers with a guitar tuner, intended to represent their music destroying capitalism. The 9/11 attacks forced them to delay the release and design a new cover. It also landed Riley a panel spot on Bill Maher’s Politically Incorrect, on which Riley addressed the controversy. He held his ground against Maher and other panelists when discussing issues like corporate influence over politicians, anti-Muslim attitudes, and being a socialist. In the end, Party Music weathered all the controversy and anger and landed on several “best of the year” lists.

Political rappers and rap groups don’t always age well; they can be corny or preachy, and they often feature messy politics that compromise their messages of revolution. To quote Greg Tate’s essay on Public Enemy’s frustrating polemics (a line that, ironically, is now a bit problematic these days), “To know PE is to love the agitprop (and artful noise) and to worry over the whack retarded philosophy they espouse.” Tate further lamented that while the group showed “sound reasoning when they focus on racism as a tool of the U.S. power structure” they were prone to dehumanizing gay men, women, and Jews.

Indeed, one big factor that keeps the Coup’s back catalog so polished is that their politics are clearer. They’re consistently socialist and tend not to lean into misogyny or anti-gay rhetoric as hard as other acts. Riley always added a bit of humor and mischief to his lines, too, bolstered by tight, funky beats. For example, cartoon executions of businessmen accompany the song “5 Million Ways to Kill a CEO” in its official music video: “You could throw a twenty in a vat of hot oil / When he jump in after it watch him boil / Toss a dollar in the river and when he jump in / If you can find he can swim / Put lead boots on him and do it again!” There’s also “Ride the Fence” off Party Music, a teardown of political centrism and a rundown of Riley’s leanings: anti-police, pro-union, “anti-watered-down drinks in expensive glasses.”

The Coup doesn’t rely on widespread manifesto after manifesto either. They narrow down on specific issues. They have two songs focused on the repossession industry and its role in punishing poor black communities for debt. Off Steal This Album! there’s “Breathing Apparatus,” which deals with the health care industry and culminates in the idea that an uninsured patient’s life is forfeited because the patient “lost the will to pay.” It’s a death sentence that would fit well into the dystopia of Sorry to Bother You, a world in which people conscript themselves into luxury prisons run by a megacorporation.

All that said, storytelling may be Riley’s biggest strength as an MC, and in that sense, it’s no surprise that he made such a successful jump to film. In “Not Yet Free,” Riley showed he could connect the struggles of inner-city life to the oppression of a broader system, and he repeats this theme in “Fat Cats, Bigga Fish.” The song follows a hustler who “got game like [he] read the directions” through what begins as a regular day of pickpocketing and conning people into giving him free meals through a decrepit city. The protagonist soon sneaks his way into a cocktail party disguised as a waiter, expecting easy, lucrative targets. Instead, he finds that the owner of Coca-Cola bottling is leveraging the mayor of his city to play up crime rates and invite developers in to clean up the town with new luxury housing. The song switches from a playful grifter’s story to a realization about gentrification and corporate lobbying. “Ain't no hustler on the street could do a whole community,” raps Riley. “I’m getting hustled knowin’ only half the game.”

In “Cars & Shoes,” also off Steal This Album!, Riley raps an ode to the broken-down jalopies in his life, similar to the dilapidated car Cash drives in Sorry to Bother You. The song is funny and relatable to anyone who’s had consistent car problems (or who’s had to rely on someone with a broken-down vehicle). But the second verse starts to hint at something deeper than Riley just being a cheapskate: He needs a car to get to work; otherwise, he could lose his job. And a dangerous, shoddy car is still more reliable than public transit: “Catchin' buses be gettin' me to work late / And you know that slow down my pay rate / Down to zero.” This song goes from a simple joke-filled rap to a realization about the hardships of the working class. The song suddenly ends with a message: With no reliable public transit, the working poor need to settle for whatever they can get, and they will still lose out in the end.

Another storytelling rap has a very direct tie to the film: “We’ve Got a Lot to Teach You, Cassius Green,” off the 2012 Sorry to Bother You album, recorded after Riley finished his screenplay. In this song, a corporation headed by literal fanged, bloodthirsty monsters tries to recruit Cash to higher ranks while they feast on human bodies — a direct stand-in for capitalists preying on their workers. The scene is a mix of gore and claws and spreadsheets, contrasted against slow, breezy instrumentals featuring synth keys, bells, and a sitar. Cash tries to leave the company, only to realize he has a monster-like tail himself. The music then shifts into a celebratory jam between an accordion and washboard as the monsters sing, “We’ve got a lot to teach you!” While the plot diverges from the film (there are no gargoyles or cannibalistic monsters in the movie), the song strikes some similar notes: The onscreen Cash also receives a warm welcome from the corporate bigwigs in the films and suffers a tragic transformation. The song seems to say that if capitalism doesn’t consume your body, it’ll twist your soul — an ominous message that can be applied to the film.

Sorry to Bother You is in many ways another contribution to the Coup’s legacy — and not just because of the soundtrack. The “bring the revolution to their doorstep” message of songs like “5 Million Ways to Kill a CEO,” “My Favorite Mutiny,” and “The Guillotine” also has a place in the movie, as workers learn they need to start fighting back (a group of mutated workers even storm a maniacal billionaire’s mansion at the very end). And while Cash isn’t a hardened hustler like the narrator of “Fat Cats,” he’s not above exaggerating, lying, or even faking his credentials to get some sort of advantage. It’s exciting to see an artist like Riley apply his artistic sensibilities to a whole new medium — and to watch him succeed.

On film or on wax, Boots Riley and the Coup are carrying on a musical tradition of revolution; they’re carrying on a hip-hop tradition of speaking truth to power. They’re also making damn good art, with a focus, a message, and tons of heart. The Coup’s discography, like many of the best political acts, proves that the revolution won’t only sound like marches, gunshots, debates, or chants; it might just sound like a party. ●

Alejandro Ramirez is a Boston-based writer and journalist whose work has appeared in Vice, the Boston Globe, Western Humanities Review, and Defunct. He is also the editor-in-chief of Spare Change News, a newspaper focused on homelessness and social justice. He received an MFA in Creative Nonfiction from the Solstice Program at Pine Manor College.