A homeless man who is mentally ill is planning to sue the Los Angeles police over four encounters with officers that he said left him hospitalized, including an incident captured on video in which five cops held him down and tased him repeatedly.

"What is particularly concerning about that video was the question of why did it go that far?" said Peter Eliasberg, an attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California. "That was totally the wrong way to deal with somebody who's having a severe mental health crisis."

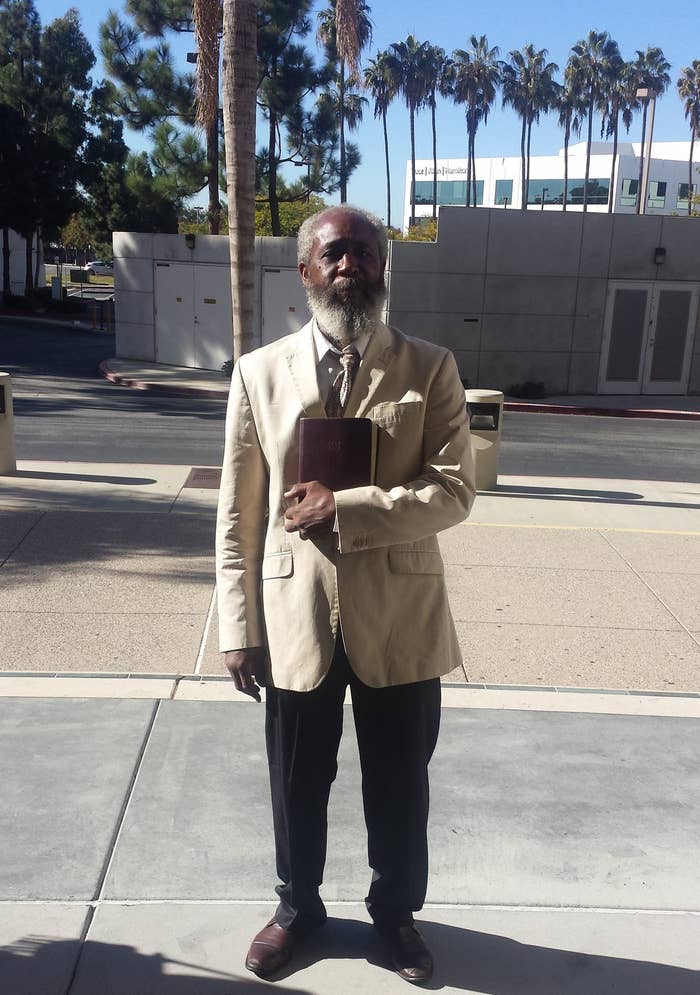

Samuel Arrington, a 50-year-old homeless man with bipolar disorder, started having violent encounters with the police as his condition worsened, his lawyer Nazareth Haysbert said. In June 2011, officers pulled him over while he was riding his bike. What exactly happened is unclear — the LAPD declined to provide any police reports for this and other incidents. But Haysbert said Arrington needed 18 staples to close a gash on his head following the arrest. He spent the next year and a half in jail, said his sister, Cleo Battle. In January 2014, he was tased during another police encounter, Haysbert said, and in July, he ended up in the hospital with a shoulder injury after an arrest.

Most recently, in the scuffle captured on video in August, Arrington was arrested for multiple municipal code violations while sitting under an umbrella tied to a public bench on Venice Beach. According to the police report, Arrington "had an open backpack placed at his feet where passersby could deposit donations." This registered at least five violations, according to the police report, including the size of the umbrella, "vending outside of a designated space," his "use of city property for vending," tampering with city property, and moving city property outside of its "designated space."

According to the police report provided to BuzzFeed News by Haysbert, officers had already warned Arrington earlier that day. When the police saw him still in the same spot at around 1:45 p.m., they wrote him a citation. They told Arrington to sign the citation, but he refused. He shouted lines about "Jehovah God!" over and over.

By the time a bystander began recording the scene on her phone, a small crowd had gathered. Some of them shouted at the officers to leave him alone. At least five officers surrounded him.

"Remove yourself from my presence or deal with the holy God!" Arrington said to the officers. "Jehovah God will handle you!"

"If you do not sign the ticket here you will be arrested," an officer said, holding the ticket out toward Arrington.

Arrington didn't take it. The officers asked him to stand up, and he didn't. Three officers converged on him and took him to the ground. Two more officers joined. With five officers pinning Arrington down, he was tased at least twice. Then they carried him away.

The video left Arrington's family wondering how a mentally ill man sitting on the beach could end up tased and thrown in jail over a citation he refused to sign. To them, Arrington was criminalized for being homeless, and then physically attacked for being mentally ill.

"There are versions of this that happen on a pretty regular basis around the country," said Maria Foscarinis, executive director of the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty. "This is an extreme example of a much larger phenomenon."

Police departments across the country have struggled to figure out how to properly deal with mentally ill individuals. Sometimes those struggles end with tragedies much worse than what happened to Arrington. In December, an LAPD officer shot and killed 25-year-old Ezell Ford. In March, an LAPD officer shot and killed 43-year-old Charly Keunang. Both Ezell and Keunang had mental illnesses, and in each case police claimed that the deceased had reached for an officer's gun.

Nevertheless, according to the federal government, the LAPD has done better than most in dealing with people with mental illness. The department has a Mental Health Evaluation Unit, staffed with 61 officers and 28 clinicians, and a special response team tasked with calming down situations involving mentally ill suspects and then placing them in a treatment facility. In 2009, a federal monitor called the department's mental health protocol "the recognized best practice in law enforcement for this subject area."

Yet according to his family, Arrington has had four violent encounters with police since 2011, and each one ended with him in the hospital. At least one of the officers who arrested Arrington in August had encountered him before. The police report stated that one officer recalled he had arrested Arrington a few weeks earlier and that Arrington "did not comply with orders." So, with that in mind, the officer "requested an additional unit." Nowhere in the police report did it say that any of the officers called for the mental health response team.

"What was the urgency? What was the exigent circumstance that caused them to act right now? There was none," said Cheryl Dorsey, a former LAPD sergeant who worked the Venice Beach beat for five years. "If he don't want to sign the damn ticket today, really how big of a deal is that? Can we finesse him into cooperating and not just bully him?"

Battle, Arrington's sister, said Arrington has had bipolar disorder for years. He lived in South Carolina when he was a small boy, in a house by a river. At 9 years old, he saw his friend fall into the river and drown. His parents sent him to a psychologist, but Battle believes that the trauma never left him.

Arrington later moved to Los Angeles, where he found work with the parks department, coaching kids' sports teams. He had two children and lived with a girlfriend for 15 years. After they split and she kicked him out, Arrington struggled, losing his driver's license and his job.

He became homeless in the early 2000s, and around this time his mental illness became more severe, his sister said. He didn't have any close family in L.A., but he chose to stay because he enjoyed living in the city and appreciated the independence he had there. Since becoming homeless, he has spent many days on the beach, listening to music on his CD player and swimming in the ocean.

The August incident appears to have been the only one of Arrington's encounters with police to be caught on video. The bystander who filmed the incident sent the footage to Haysbert, who plans to file suit against the LAPD on Arrington's behalf. Haysbert also sent a letter to the Department of Justice requesting an investigation. The LAPD declined to comment for this story, citing the potential lawsuit.

"They mistook disability for noncompliance," Haysbert said. "They were treating him like a criminal instead of a person with a mental illness."

After the officers carried Arrington off Venice Beach, they took him to a hospital. Then they took him to jail. They had left his backpack and his bike — all of his possessions, including his ID — at the beach. Less than two weeks after the arrest, the district attorney's office dropped the charges against Arrington and he was released. When he returned to the beach, his sister said, his belongings were gone.