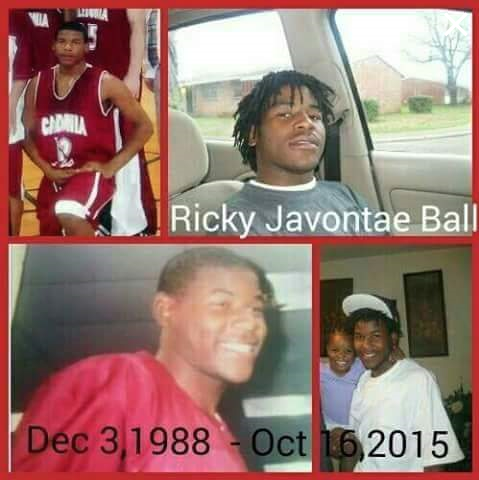

The fatal police shooting of Ricky Ball in October 2015 convulsed the city of Columbus, Mississippi. Residents marched. Some businesses, fearing a race riot because a white cop had killed a black man, closed on protest day. A city council member accused the department of planting a gun beside Ball’s body. The police chief resigned. The district attorney called in state authorities to handle the case.

Finally, in September 2016, a grand jury indicted the officer, Canyon Boykin, on manslaughter charges. Boykin’s case still hasn’t gone to trial, but if the recent past is anything to go by, he’s likely to make it through without punishment — and even walk away from the case ahead, handed money for his troubles. That’s because shortly after he shot 25-year-old Ball as Ball ran away following a traffic stop, Boykin sued the city for racial discrimination, claiming he’d been unfairly fired for being a white cop who’d killed a black person. Just before his discrimination lawsuit was to go to trial last year, the city settled with Boykin for an undisclosed amount.

“That’s what really made me realize how much is stacked against us,” said Ricky’s cousin, Ernesto Ball, who is 46. “That’s the moment I began to think that maybe these cops can really get away with whatever.”

Over the past decade, at least 25 white officers have sued their cities for racial discrimination, according to a BuzzFeed News review of media reports. Eleven had their cases rejected by a judge or jury. Nine, though, won jury verdicts at trial or reached monetary settlements, all after claims the officers had been passed up for promotions because of their skin color or fired for saying something interpreted as racist. The other cases are pending. None of those police lawsuit victories or settlements involved a fatal shooting — until Boykin’s case, which occurred as cops across the country seemed to be facing a reckoning over their use of force. In the months before and after Boykin's indictment, officers involved in seven high-profile shootings — in Albuquerque, New Mexico; North Charleston, South Carolina; Cincinnati; St. Louis; Tulsa, Oklahoma; Milwaukee; and Falcon Heights, Minnesota — were criminally charged. Boykin, 28, claimed he’d been swept up by this wave of outrage and was a victim of “uninformed public pressure.” He would not have been fired, his lawsuit stated, “except that he is white and the deceased was black.”

“I don’t have any faith in the justice system anymore.”

Since Boykin’s indictment, the officers in those seven high-profile police shooting cases have all gone to trial, and not one was convicted in state court. The outcomes revealed a reality that is becoming increasingly clear: Investigators, prosecutors, judges, and juries can try to hold officers accountable, but none of that matters when laws continue to protect any cop who says they feared for their life before pulling the trigger.

“I don’t have any faith in the justice system anymore,” Ernesto said. “At first I was excited. At first I thought that maybe it would be something quick. But as time goes on, and things start happening… It’s hard, man. It’s hard to keep that belief I been trying to keep.”

Ricky had encountered Boykin at least once before. He’d befriended a relative of Boykin’s, and one day in August 2015, he drove with her through the neighborhood. Boykin, who’d been on the force for three years, and his partner, Max Branch, followed the blue Hyundai, calling into dispatch that they were about to pull it over.

“Be a black driving, white female passenger,” Boykin said into the radio, according to a transcript of Branch’s body camera. Boykin’s camera was not on, which is a violation of department policy.

“Who’s driving?” Branch asked.

“I don’t know,” Boykin replied. “I can’t remember his fucking name. I seen him one time over by Ash Street.”

The cops flashed their lights, the car didn’t stop, the cops gave chase — losing it down a side street before eventually catching up. They found the car stopped.

“God, please still be in the car motherfucker,” Boykin said. “Please still be in the fucking car. If I get my fucking hands on him…Goddamn it, motherfucker.”

“He going to jail no matter what. No matter what he was going to jail.”

“You going to whoop his ass?” Branch said.

“Yeah,” Boykin said. “He going to jail no matter what. No matter what he was going to jail.”

Ricky was gone by the time they got to the car.

“He did the right thing by fucking running,” Boykin said.

The cops were part of a special unit tasked with patrolling high-crime areas. The unit’s presence was heaviest in Ricky’s neighborhood, Memphis Town, a moniker bestowed in the 1940s by the black service members from the nearby Air Force base who declared that the juke joints and restaurants on 14th Avenue reminded them of Beale Street in Memphis.

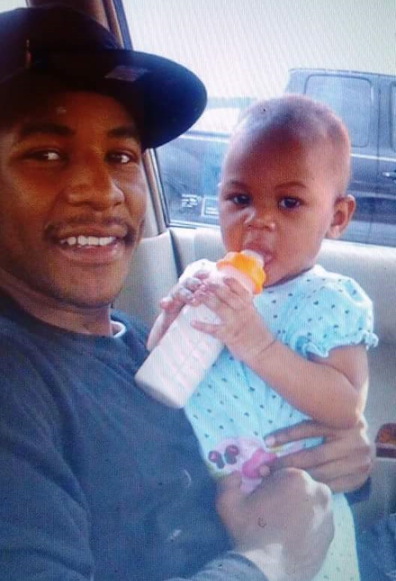

By the time Ricky was growing up, those businesses had closed, along with most of the factories that employed a large swath of the city’s population, which had doubled from 1940 to 1980. A basketball star in high school, Ricky was well known around the neighborhood. He was charming and quick-witted, those who knew him say, and was always making people laugh. In his early twenties, he had a daughter. He made money dealing drugs. In June 2013, he sold weed and cocaine to a police informant and was indicted on two felony counts, charges that were pending the night he died.

Then-city council member Marty Turner and other Memphis Town residents accused the “hot spot” squad of harassing black residents. One man, Don Deloach, reached an undisclosed settlement with the city in October 2014 after four police cars pulled up to him early one morning in a Kmart parking lot. When Deloach demanded to be told what he’d done wrong, Boykin arrested him, according to court documents. Deloach, the Kmart manager, was there to open the store. The incident was captured by another officer’s body camera. Boykin’s camera was off, and he was suspended three days as a result.

Two months after that run-in with Ricky Ball, Boykin and his partner attempted to pull over a white Mercury. It was a little after 10 p.m. when the officers, in an unmarked patrol car, spotted the Mercury heading in the opposite direction.

Branch was at the wheel, Boykin beside him in the front, and in the back seat were Officer Yolanda Young, who was their supervisor, and Alisha Stanford, Boykin’s girlfriend. Stanford sometimes joined him on ride-alongs. The three cops said that they all saw that the Mercury’s back license plate light was out, and that there was a white woman in the driver’s seat.

The cops followed the car down the street, blue lights flashing, but the Mercury kept moving forward at a crawl, the three officers told state investigators. As they drew closer, the cops said they noticed a man in the front passenger’s seat. They also said his door was open slightly, a sign he planned to run. Boykin cracked his own door open and got ready to give chase. The car turned onto a residential street next to a vacant lot, hit a speed bump, then slowed even more. Ricky jumped out and ran. Boykin went after him. All three officers’ body cameras were off. Seconds later, Branch radioed dispatch: “Shots fired!”

It was dark, the closest streetlight nearly half a football field from the lot. Boykin would tell investigators that he tased Ricky on the street, a few feet from the car, and saw a gun in his hand when Ricky fell to the ground. Boykin said that he dropped his Taser and drew his own gun, as Ricky got back on his feet and took off running across the grassy lot. Boykin said that when Ricky was about 25 yards away, Ricky turned toward him and pointed a gun. That’s when Boykin opened fire. Two of the eight shots struck Ricky: one in the hip, another going through his arm and into his chest, hitting an artery.

Ricky kept running. Locals stepped out of stores and houses upon hearing the gunfire, curious to see what was happening. Two told me they heard Ricky shouting, “Help, they trying to kill me!” while he ran. The officers called for backup and searched the area. Ricky was still alive when an officer found him beneath a mobile home. Responding officers also found a gun, a pouch of weed, and a container of cocaine stashed in a cinder block hollow an arm’s reach from Ricky. Twenty-one minutes after the report of shots fired, paramedics arrived. Ricky was pronounced dead at the hospital.

“Help, they trying to kill me!”

The medical examiner concluded that the location of the bullet holes in Ricky’s body didn’t make clear whether he was pointing a gun when he was shot or whether he was just looking behind him while running. While some residents believe the gun was planted — it was registered under the name of a local cop who was securing the scene that night — the gun had been reported stolen from the cop’s house in a burglary two months before Ball’s death, police investigative reports confirm.

Within days of the shooting, investigators questioned Branch and Young, the two officers who were with Boykin. Both said they heard Boykin shout, “Gun! Gun! Gun!” but neither saw a weapon. Branch said his eyes were on the woman in the Mercury driver’s seat the whole time. Young said she observed Ricky looking back at them as he ran but she didn’t see anything in his hands. When investigators asked her if Boykin gave any commands to Ricky before firing, she said, “I didn’t hear nothing. Nothing but the shots.”

On a recent afternoon in early June, the sky bright and the air sticky, Ernesto and I walked across the grassy lot where his cousin was shot, retracing those final, frantic steps past the big tree, across the ditch, around the half-vacant apartment row, and into the yard behind the mobile homes perched on cinder blocks. Ernesto knew the way because he’d followed the blood trail the morning after the shooting.

Oldest among his generation of cousins, Ernesto helped raise Ricky. After the birth of Ricky’s daughter six years ago, Ernesto shared babysitting responsibilities. When Ricky needed a place to stay, Ernesto let him and his girlfriend move into his house. And when Ricky died, it was Ernesto who spoke at city hall, led the marches, handled media requests, and educated himself on the court system that will decide whether or not his cousin was unjustly killed.

Laws covering police deadly force in most of the country trace back to British common law, written into early state penal codes when guns were less lethal and the death penalty was applied to burglary, sodomy, and slave rebellion, among other crimes.

As of 1984, it was legal in most states for an officer to fatally shoot any suspected felon attempting to flee. That year, a Memphis police officer killed 15-year-old Edward Garner. The officer, Elton Hymon, said he assumed Garner was unarmed but fired anyway because he spotted the boy running from the scene of a reported burglary attempt. The officer was not charged, but Garner’s father sued the city, and the case reached the Supreme Court, which ruled in 1985 that Garner’s Fourth Amendment rights had been violated. An officer can’t shoot somebody running from them unless they have “probable cause to believe that the suspect poses a significant threat of death or serious physical injury to the officer or others,” the 6–3 majority opinion stated.

That standard, paired with another ruling four years later saying use of force must be “objectively reasonable,” set constitutional limits, but it doesn’t dictate criminal code. Mississippi is one of 16 states yet to update their police deadly force statutes to meet constitutional requirements, leaving judges and juries to make decisions based on a patchwork of legal standards that make it nearly impossible for an officer to be found guilty of murder or manslaughter. In another of those 16 states, South Carolina, a jury was unable to reach a verdict in the 2016 trial of an officer caught on video fatally shooting a fleeing, unarmed man in the back from yards away.

"Did the officer have other alternatives? Did the officer really put the sanctity of human life first?”

“People are outraged when juries return an acquittal, and they don’t realize jurors may have had genuine reasons to be divided or confused,” said Brandon Garrett, a law professor at Duke University. “Often it’s unfair to blame the law,” he said, but police deadly force law “really is genuinely confusing and out-of-date.”

Even in states with more restrictive use-of-force laws, a cop’s proclamation of fear can be enough to avoid prison, no matter the circumstances. The law generally “tells jurors to look through the eyes of the officers,” said Craig Futterman, a criminologist at the University of Chicago. “It doesn’t ask: Did the officer have other alternatives? Did the officer really put the sanctity of human life first?”

In the wake of the failed convictions of the past four years, elected officials and advocates for police accountability have set their sights on changing deadly force laws. State legislators in Washington have proposed eliminating a provision that absolves officers who kill unless there's proof they acted with “malice”; lawmakers in California introduced a bill to raise the standard for a justified police killing from “reasonable” to “necessary” and to require jurors to consider the role an officer played in escalating an encounter. If it passes, California would have the nation’s toughest law governing police use of deadly force.

“We give police officers an extraordinary amount of power,” said Futterman. “There’s a reticence by most of society, jurors included, to find officers guilty of violating people’s rights because it would be a very scary world to most folks if people believe that the people we entrust to protect us are out there abusing us, which is sadly the reality for many black and brown communities.”

In many cases, the only sanctions an officer faces for a fatal shooting come through the city government, which can strip away jobs, wipe out pensions, and change department policies. Often, these local penalties are doled out long before a case makes it to trial — a dose of accountability to try to pacify an outraged public.

Going against the wishes of Columbus Police Chief Tony Carleton, city council members fired Boykin two weeks after Ball’s death — not for the shooting, but for repeatedly violating department body camera rules, allowing his girlfriend to ride along without authorization, and posting a series of inappropriate memes on social media, including one that used the n-word. (His lawyer argued that the usage was intended as slang rather than as a pejorative.) Boykin had offered to resign, but the city council rejected it; as then-council member Marty Turner reasoned, allowing Boykin to quit would have made it easier for him to find a job with another police force.

Chief Carleton resigned the next day and soon took a job with the Oxford, Mississippi, police department. Over the next several weeks, an assistant chief and a narcotics officer also resigned. The hot spot task force was disbanded. The penalty for failure to turn on a body camera was lengthened from a three-day suspension to 10 days. And when Boykin sued, the city planned to let the case go to trial.

But two weeks before it was set to start, City Attorney Jeff Turnage shifted course. The city’s insurance company informed him that it preferred a settlement over risking a loss at trial or higher legal costs, he said.

In addition to the financial compensation, the city rescinded Boykin’s termination. “Our official position is that he resigned,” Turnage said. “And that we never technically fired him in the first place.”

To Ernesto and other black residents, the city seemed to be saying that it would have been better off had it never moved to punish Boykin.

Jurors don’t always give cops the benefit of the doubt. Of the thousands of fatal police shootings over the last decade, at least 21 have led to convictions, according to a BuzzFeed News review of media reports and a Washington Post database of recent police shootings. In some of those cases, eyewitness testimony was enough to convince a jury that an officer wasn’t justified in shooting.

One of the most important eyewitnesses in the Boykin case, Officer Yolanda Young — who said she saw no gun in Ricky’s hands — may not be able to speak in court. In the years since the shooting, she was diagnosed with cancer, suffered a series of strokes, and has been immobilized in a hospital, according to court documents. A judge must now decide whether her earlier statements to investigators will be admitted if she is unable to testify. Another witness, Chris Shelton — who drove past the scene as the shots were fired — lost touch with investigators after getting a new phone, before only recently tracking down the number to reach them. The more time passes, Ernesto fears, the more chance witnesses will drop out and memories will fade, putting doubt in jurors’ minds. There isn’t much physical evidence to help sway a jury.

No trial date has been set yet. Because the case was so well known locally, the judge ruled that the jurors would be selected from Walthall County, near the Louisiana border. Boykin still lives in Lowndes County, where Columbus is located, and works at an industrial plant just over the Alabama border, “making less money” than he did as a cop, his lawyer, Jeff Reynolds, told me. “Since he was a little boy, all he has ever wanted to do is be a police officer, so he very much looks forward to the day he can once again work as a law enforcement officer,” Reynolds said.

“Every time one of ‘em gets away with killing one of us, that just makes the rest of ‘em think they can do whatever they want.”

Meanwhile, Ernesto has worried about the prospect of police intimidation. Days after he led the protest, he was pulled over by four cruisers, he said, and asked where he was coming from and where he was going without being told why he'd been stopped. Another time, he said, an officer pulled up beside him and said out an open window, “Don’t get shot,” before driving away. One night, he encountered an officer walking around the back of his house, shining a flashlight; the officer said he was in the area on a call, Ernesto said.

What angers him now, when he thinks back to all that has happened in the years since his cousin was killed, is the aura of indignation and immunity emanating from many of the officers he sees. “Every time one of ‘em gets away with killing one of us, that just makes the rest of ‘em think they can do whatever they want,” he said. “This is why it keeps happening.”

He still can’t get out of his head the image of Boykin leaving the county jail after making his $20,000 bail. A line of supporters clapped and cheered him on, some of them in police or sheriff’s deputy uniforms. ●