Just a few years ago, the NFL seemed to be facing compounding existential crises. New studies revealed that playing football put people at a significant risk of severe degenerative brain damage. Players were committing acts of shocking criminal violence. The country’s political polarization meant there were dueling boycotts over players kneeling during the national anthem and the league’s response to it. Television ratings started to dip after 2015, fewer kids were signing up for the sport, and celebrities were speaking out against it. People asked: Were football’s days as America’s pastime numbered?

Rihanna declined an invitation to perform at the Super Bowl halftime show in 2019. "I couldn’t dare do that,” she said at the time. “I just couldn’t be a sellout. I couldn’t be an enabler. There’s things within that organization that I do not agree with at all, and I was not about to go and be of service to them in any way."

The problems plaguing the league over the last decade haven’t dissipated. In fact, they seemed to coalesce from all angles over the past year.

In February 2022, shortly after he was fired as the Miami Dolphins’ head coach, Brian Flores, who is Black, sued the league for racial discrimination in the hiring process for coaches, listing examples of teams calling him in for an interview to fulfill the league’s diversity requirements only to hire another candidate before the interview had even taken place (as he said the Buffalo Bills did), or interviewers showing up an hour late and hungover (as he said the Denver Broncos did). (The NFL has said that Flores’s claims are “without merit,” and both teams disputed his version of events.)

In May, Colin Kaepernick invited NFL teams to watch him throw passes at a private workout in hopes of showing he was good enough for a new contract. Still, nobody signed him, marking his sixth straight season out of the league.

In September, Miami Dolphins quarterback Tua Tagovailoa suffered his second concussion in four days. It was severe enough to elicit a fencing response, leaving the primetime audience with the terrifying sight of his body seized up and his fingers disturbingly flexed.

Cleveland Browns quarterback Dashaun Watson, who signed a record-breaking $230 million contract while facing an 11-game suspension based on the claims of 24 women who said he sexually abused them, made his return to the field in November. (Watson has said the encounters were consensual and reached settlements on most of the lawsuits.)

And in early January, Buffalo Bills defensive back Damar Hamlin collapsed from a cardiac arrest after making a routine-looking tackle in the first quarter, an incident so shocking and traumatic that players and coaches decided the game couldn’t go on. It was the first time an NFL game has been canceled due to an injury.

Yet more people are tuning into games on Sunday. More people are buying tickets to games than even before the pandemic. TV deals grow more lucrative with each contract. No players kneel anymore. And this weekend, to cap off what has seemed like a cursed football season, Rihanna is headlining the Super Bowl LVII halftime show.

The league has continued to thrive, having calculated the minimum standard of carefully weighed incremental progress. Its playbook for survival is simple: Do just enough to keep most of us from turning away.

Kaepernick entered the NFL at the dawn of the converging crises. His rookie season, 2011, came on the heels of two landmark studies linking football to the degenerative brain disease chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

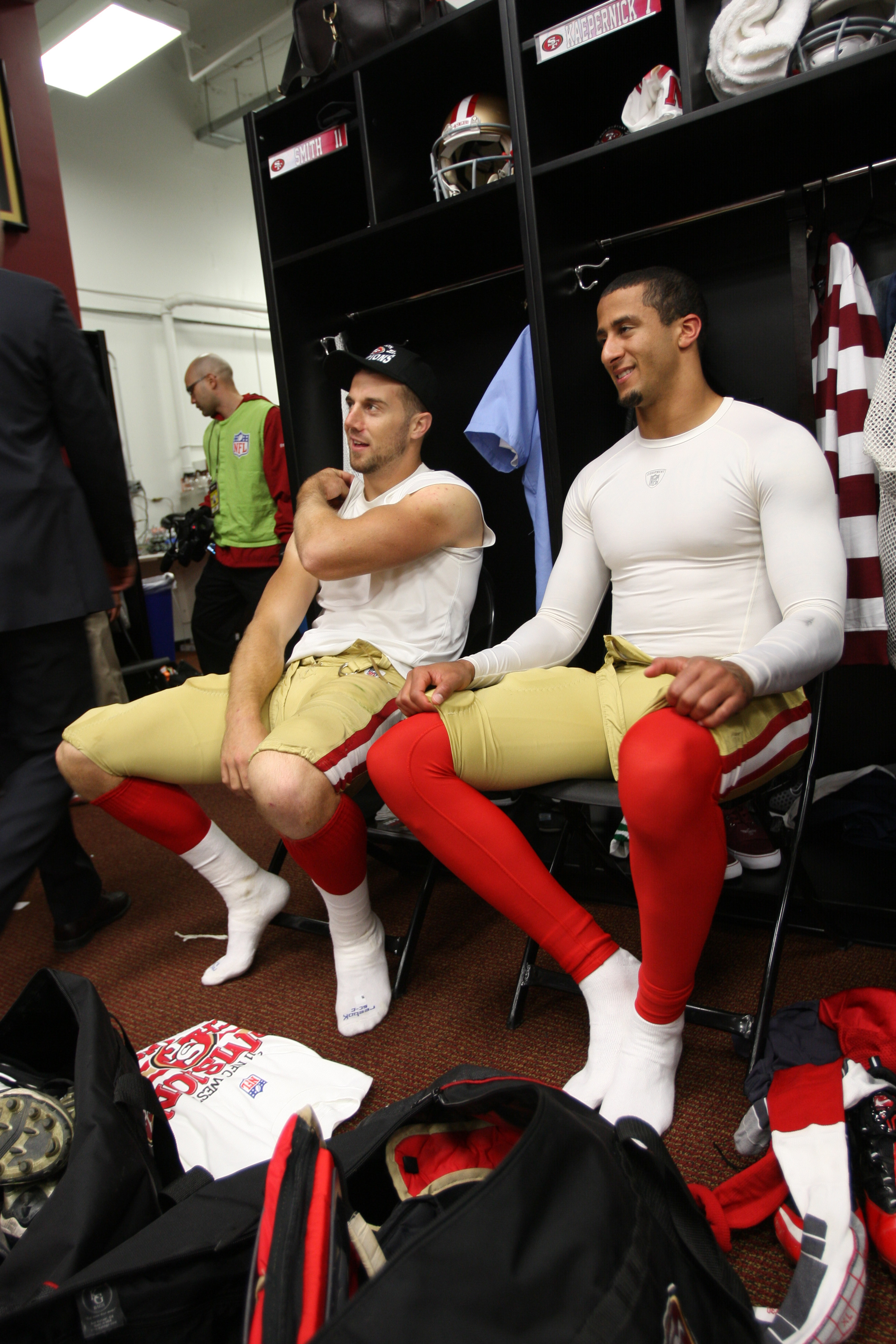

He began his second season as a backup quarterback on the San Francisco 49ers. When the starter got injured midway through the season, in November, Kaepernick took the reins.

A month later, 25-year-old Kansas City Chiefs linebacker Jovan Belcher killed his girlfriend and then himself; an autopsy of his brain showed signs of CTE.

In the weeks that followed, Kaepernick led his team to the Super Bowl, rising to fame for his exciting playing style, celebrating touchdowns by kissing his tattooed biceps, and breaking the NFL single-game record for rushing yards by a quarterback along the way.

The following summer, 23-year-old New England Patriots tight end Aaron Hernandez was charged with murder. He was convicted, then killed himself in prison. His brain showed “severe” signs of CTE, according to the neurologists who studied it.

Local politicians in six states proposed bills banning tackle football before ninth grade. Pop Warner, the country’s oldest and biggest youth football league, experienced its first-ever decline in participation nationwide. High schools in California, New Jersey, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Missouri, and Iowa shuttered football programs because not enough kids were signing up. From 2008 to 2017, the number of kids playing high school football declined by 6.6%, and then by another 4% from 2019 to 2022, according to data from the National Federation of State High School Associations.

In response to concerns over brain trauma, the league added a protocol aimed at keeping concussed players out of action until they had fully healed as well as more rules penalizing or eliminating some of the game’s most violent collisions.

After Tagovailoa’s September 2022 concussions, the league expanded the list of symptoms that would bar a player from returning and installed a “spotter” at each game tasked with identifying players who should be tested for a head injury.

But studies have shown that concussions are only part of the problem. The countless “sub-concussive” hits a player accumulates over the years is a primary cause of CTE, according to the neurologists who study it.

There’s always a fresh batch of young players toiling to earn a roster spot and its six-to-seven-figure salaries.

Over the last decade, more retired players began speaking up about their cognitive deficiencies, including heightened aggression, depression, memory loss, and dementia. Around 4,500 former players filed a class-action lawsuit in 2012 holding the NFL responsible for long-term brain damage they’d suffered. In August 2013, the NFL agreed to a $765 settlement without admitting fault. In 2020, the league settled another lawsuit claiming that hundreds of Black players had been denied access to the initial settlement money because of a discriminatory medical evaluation process that downplayed their brain damage. This week, 10 retired players filed a new lawsuit alleging that the league steers disability claims toward doctors financially incentivized to deny them.

In negotiations with the players’ union, the league refused to consider lifetime healthcare coverage for former players, offering coverage only through their first five years of retirement, and agreed to provide pensions only for those who play at least three seasons. But in 2022, when Hamlin’s career was in jeopardy after his cardiac arrest during his second season, league officials announced that it would make an exception for him and provide a pension even if he doesn’t return to the field — an example of the league snuffing out small PR fires without addressing the systemic problems at their root.

Some players started retiring early, in their 20s or early 30s, citing the sport’s physical toll. But the average NFL career lasts around three years; there’s always a fresh batch of young players toiling to earn a roster spot and its six-to-seven-figure salaries.

Violence is a common thread stringing together NFL scandals. The league’s most controversial decisions have aimed to distinguish what kind of violence should be banned, punished, protested, and celebrated.

In September 2014, a video of Baltimore Ravens running back Ray Rice punching his wife and then dragging her unconscious body out of an elevator raised questions about the league’s decision to suspend him for just two games. After a widespread public outcry, the league made the suspension indefinite, though an arbiter later ruled the NFL couldn't change a punishment when it had already seen all the evidence upon issuing the initial discipline. A Sports Illustrated investigation reported that “from Jan. 1, 2012 to Sept. 17, 2014, 33 active NFL players were arrested on charges involving domestic violence, battery, assault and murder.”

Serious questions proliferated: Did football draw people prone to violent behavior or was the league an incubator for it, rewarding young men for brutality that served them well on the field but caused harm off it? Was the rash of violence caused by early stages of the brain damage researchers were finding in nearly every former player they studied? Was America funneling waves upon waves of ambitious and athletic boys into a sport that was ruining their minds?

Following the Ray Rice video, the NFL lengthened suspensions for certain violations, created a new internal investigations unit, and mandated a preventive training program for players that included testimonials from sexual assault and domestic violence survivors.

Did football draw people prone to violent behavior or was the league an incubator for it?

Indeed, over the following years, players accused of domestic violence, including Greg Hardy and Kareem Hunt, were disciplined with suspensions more severe than what the league had previously given. But in a country that has long celebrated redemption arcs, America’s sport maintained a belief in second chances — as long as they gave a team a better chance at winning. After Deadspin published photos of his ex-girlfriend’s injuries, no team signed Hardy, a defensive lineman who turned 27 during his suspension and had a reputation for bringing a bad attitude into the locker room. But Hunt, a 23-year-old running back who showed glimpses of stardom before he was caught on video kicking a woman at a hotel, signed a contract with the Cleveland Browns after completing treatment for anger management and substance abuse.

The potential for redemption offered an ethical defense to teams looking to draft players who’d been convicted of domestic violence during college. Tyreke Hill, a speedy wide receiver drafted by the Kansas City Chiefs after pleading guilty to choking his girlfriend, and Joe Mixon, a powerful running back drafted by the Cincinnati Bengals after a video showed him punching a woman in the face, both helped push their respective team to the Super Bowl within five years of entering the NFL.

Winning games is the surest path to forgiveness.

Kaepernick followed up his Super Bowl appearance with an even more impressive season, establishing himself as one of the best quarterbacks in the league. He led the Niners deep into the playoffs before falling one game short of the Super Bowl. At that point, it felt as if his ascent was only beginning.

Unfortunately for Kaepernick, wins suddenly began to become elusive. Though his 2014 season started well, he ended it on a rough patch that knocked the Niners out of playoff contention. He struggled through the first half of the following season, then missed the rest of it with a shoulder injury. By the start of the 2016 season, he was competing to remain the team’s starting quarterback.

That was the backdrop when he started protesting police brutality in August 2016, two years after an officer in Ferguson, Missouri, killed Michael Brown.

During the national anthem before each of the first three preseason games, he sat on the bench far behind his teammates lined up standing along the sideline, but nobody really noticed. For the fourth game, he switched from sitting behind his teammates to kneeling beside them, on the advice of fellow NFL player and former Green Beret Nate Boyer, who likened the act to when “soldiers take a knee in front of a fallen brother’s grave to show respect,” as he said on an episode of HBO’s Real Sports.

Soon, everybody noticed. Kaepernick’s protest became a foundational symbol in the months leading up to a highly polarizing and ground-shaking presidential election, as Donald Trump called him out in speeches as an example of the America he was fighting against.

Kaepernick played in 11 games that season but won just one. At the end of the season, the Niners declined to re-sign him. No other team signed him, either. His stretch of losing served as convenient evidence for those arguing that his declining performance was the reason no team wanted him. Even though the Niners had one of the worst defenses in the league, a quarterback carries most of the credit for a team’s wins and most of the blame for a team’s losses. Anonymous team officials called his protests a distraction. He was not getting a second chance, his critics said, because he was an impediment to the single-minded focus required to fuel a football team’s success.

But statistically, Kaepernick’s performance in his final season was above average. In a league where talented quarterbacks are hard to come by, the collective decision to pass on hiring Kaepernick was a historic outlier. A data analysis by Jon Bois calculated that, based on numbers alone, Kaepernick is far and away the best quarterback to ever go unsigned. He’d ultimately reach a settlement with the NFL in his lawsuit accusing teams of blacklisting him.

The protest movement he started carried into the next season, with other players continuing to kneel during the anthem. Some conservatives declared a boycott of the NFL to protest what they saw as disrespect of the flag. Some liberals declared a boycott to protest the conspiracy against an accomplished quarterback just a few years removed from leading a team to the Super Bowl.

In 2019, the league partnered with Jay-Z on an “Inspire Change” initiative donating $250 million over 10 years to social programs focused on “education and economic advancement,” “police and community relations,” and “criminal justice reform” — an amount that equates to about half of what a single top quarterback will earn over that period. And just to make its philosophical position as clear as possible, the NFL painted on every field the words “IT TAKES ALL OF US” and “END RACISM.”

Under the guise of promoting unity, the league took the path of least resistance.

With a business model predicated on reaching an audience that spans America’s ideological spectrum, the league’s response to police brutality protests was to select the blandest, broadest, most universally appeasing message imaginable. Under the guise of promoting unity, the league took the path of least resistance: Surely we can all agree we want to end racism.

As protests swept the country in June 2020 after the police killing of George Floyd, the league tweeted a video statement from commissioner Roger Goodell, with the caption: “We, the NFL, admit we were wrong for not listening to NFL players earlier and encourage all to speak out and peacefully protest. We, the NFL, believe Black Lives Matter. #InspireChange.” This is not an institution that uses its power to inspire change but one that flows with the tides. When the masses shifted toward the message Kaepernick and his fellow protesting players had been promoting for years, the NFL was quick to recalibrate its official stance.

That summer, an interviewer asked Goodell what he would say to Kaepernick now.

“The first thing I’d say is I wish we had listened earlier, Kaep, to what you were kneeling about and what you were trying to bring attention to,” Goodell said.

Football, like the rest of America, has deep roots in racist ideology. The NFL was almost exclusively white when it was founded in 1920. By mid-century, some teams still had no Black players and most teams maintained a quota that kept the league majority white. A competitor, the American Football League, sprung up in 1959, signed on the Black players the NFL passed on, and rose to prominence so quickly that it merged with the NFL in 1976.

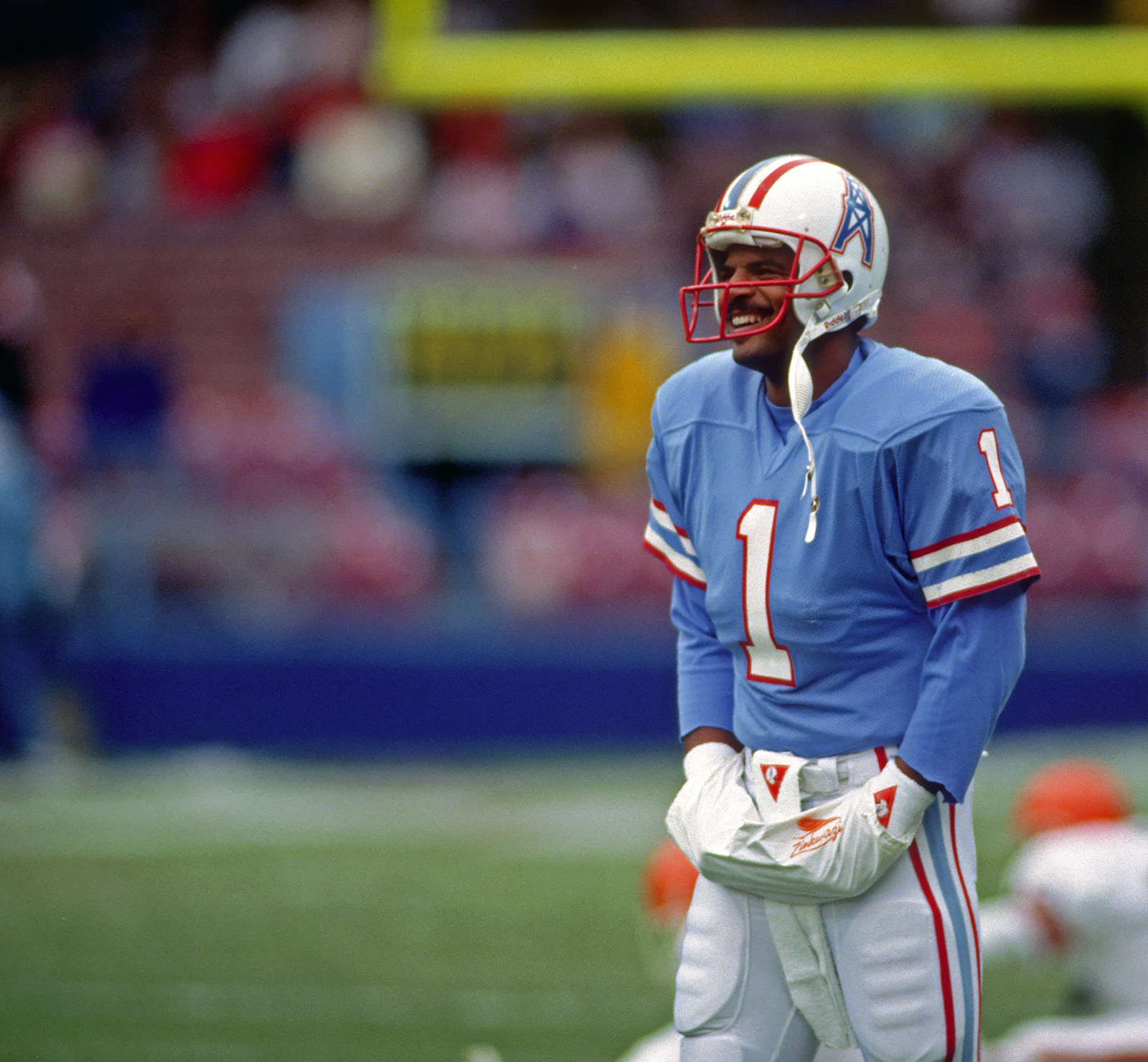

Even as the league accepted more Black players, persistent racist beliefs ensured that few of them played the most important and well-paid position, quarterback. The first Black quarterback inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, Warren Moon, spent six years in the Canadian Football League, winning five consecutive championships, before an NFL team offered him a job in 1984. He was the only Black quarterback in the league that year.

Four years later, Doug Williams, who began his professional career in the short-lived United States Football League, became the first Black quarterback to start in the Super Bowl.

The second, in 1999, was Steve McNair, who had been a star high school quarterback, turned down top-tier college programs because they wanted him to switch to running back or defense, and went on to set records at the smaller Alcorn State on his way to a standout NFL career.

The third Black quarterback to start a Super Bowl, in 2004, was Donovan McNabb, who once said that he avoided using his speed to run for yards because he didn’t want to perpetuate stereotypes that Black people lacked the precision and intellect to play quarterback.

A game of conquest in the land of manifest destiny, violence in the land of military supremacy, and unequally shared labor and glory in the land of capitalism.

The fourth Black quarterback to start a Super Bowl was Kaepernick, in 2013 — 10 years ago this month — the pinnacle of a career that seemed so bright at the time.

The backlash against him reflected football’s place as a pastime that embodies America’s most closely held virtues: a game of conquest in the land of manifest destiny, violence in the land of military supremacy, and unequally shared labor and glory in the land of capitalism.

Though 58% of the players risking their bodies on the field are Black, just 11% of head coaches are, and not a single owner is. All owners are white, except two; one of them, Shadid Khan of Jacksonville, donated $1 million to Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign.

Houston Texans owner Bob McNair, who has since died, called players “inmates” during a league meeting over how to handle anthem protests in 2017. Daniel Snyder, owner of the Washington, DC, franchise, staunchly resisted calls to change his team’s racist name for years, impeded investigations into sexual harassment within his organization, and then faced his own allegations of groping a woman without consent on the team plane. (Snyder has denied each of those accusations.)

In October 2021, Jon Gruden resigned as head coach of the Las Vegas Raiders after emails surfaced showing that he said DeMaurice Smith, who is Black and executive director of the NFL players’ union, had “lips the size of michellin tires [sic].”

In June 2022, Jack Del Rio, an assistant coach for the Washington Commanders, said in a press conference that he didn’t understand why the US government was investigating the January 6, 2021, “dust up at the Capitol” but not the summer 2020 “riots” following the police killing of George Floyd.

In November, the Washington Post unearthed a 1957 photo showing Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones in the back of a crowd of white teens blocking Black classmates from entering the high school they were integrating; he said he was just observing and not a part of the racist group.

Since buying the franchise in 1989, Jones has hired eight head coaches, all of them white. The Cowboys are one of 13 teams to have never had a Black head coach.

You could argue that everything worked out fine for Kaepernick. In exchange for giving up the sport he loved, he has become a civil rights icon with a multimillion-dollar Nike endorsement deal and a media production company — all without risking long-term brain damage.

You could argue the fate of those who remain in the sport is more concerning than the plight of the famous quarterback excluded from competition.

An HBO Real Sports investigation researching high school football participation in Illinois from 2015 to 2019 found a 25% increase in the proportion of players who came from low-income families, as measured by their eligibility for free or reduced lunch.

In other words, the people who continue to play football are increasingly those who can’t afford to miss out on the opportunity it provides. Football is a billion-dollar industry that supplies more college scholarships than any other extracurricular activity and draws recruiters from private high schools into marginalized communities to offer full financial aid to promising young athletes. For those locked out of America’s wealth, football offers a path to otherwise unattainable resources.

Millions continue to watch the NFL, fueling the lavish television rights deals that generate the bulk of the league’s income. The game is more entertaining than ever before. Rules intended to make it less violent have also made it faster paced and more high scoring. Speed matters more than strength; players choose savvy over toughness, tactical brilliance over brute force. You see fewer memorable hits but more spectacular catches.

For those locked out of America’s wealth, football offers a path to otherwise unattainable resources.

At the forefront of the game’s evolution are the quarterbacks facing off in this year’s Super Bowl, Patrick Mahomes and Jalen Hurts, field generals helming innovative offenses that generate flashy highlights unlike anything we’ve seen in previous eras. Mahomes, a 27-year-old passing genius who has carried his Kansas City Chiefs to three of the last four Super Bowls, is widely considered the league’s most valuable player and has already drawn comparisons to all-time greats like Tom Brady, Peyton Manning, and Joe Montana. Hurts, poised beyond his 24 years and strong enough to squat 600 pounds, emerged as a breakout star this year as his Philadelphia Eagles streaked to the league’s best record.

For the first time in NFL history, both starting quarterbacks in the Super Bowl are Black.

I have no plans to abandon the sport just as a new generation of young stars promises to bring years of excitement to my autumn Sundays. But I am of a generation that grew up with football. My uncles and older cousins taught me the game. My closest high school friends played it with me under the Friday night lights. My best friends in adulthood gather with me in crowded bars or comfy living rooms to indulge in a weekly ritual that lives on through the guilt.

Maybe I am doomed to a lifetime of football. But before me, there were those who couldn’t escape baseball, and before them, those irrevocably tangled in horse racing and boxing. Tastes change with the times, and there is no doubt that football carries the flavor of an antiquated age.

Football’s hold on my generation might be secure, but I wonder if today’s American 12-year-olds dream of becoming Lionel Messi or Kylian Mbappé the way 12-year-old me dreamed of becoming Michael Vick or Randy Moss. Do they rise even earlier on Sundays than I did because English Premier League games kick off six hours before the NFL? When my friends who are grade-school teachers tell me about the students who sneak-watch World Cup games on their phones during class, I wonder if it marks an early paradigm shift away from a game defined by violence toward one less dangerous for players but with its own deeply rooted corruptions and human costs. Can America’s brutal sport survive the rise of a generation far more socially conscious and globally connected than any before it?

To those profiting from the league now, the answer doesn’t matter. They won’t be around to deal with the consequences. The games will change without them. ●