Where were you when you learned that Manti Te’o got catfished?

Were you reading Deadspin’s scoop on your iPhone 5 while “Gangnam Style” boomed from your new Beats Pill speakers? Did the news interrupt your effort to catch up on Season 2 of Game of Thrones? Was the juicy, low-stakes scandal just the distraction you needed after a long day calling congressional representatives urging them to vote for the gun control bill then-president Barack Obama proposed after a man killed 20 first-graders at Sandy Hook Elementary School?

For days in January 2013, the biggest news story in the country was the revelation that a 21-year-old college football star had dedicated his season to a dead girlfriend who didn’t exist.

Te’o was already pretty famous before most of us knew anything about his relationship. He was a charismatic, talented, God-fearing linebacker at Notre Dame, one of the most prominent institutions in the sports world, and by the end of his junior year, experts were projecting him to be a first-round pick in the NFL Draft.

Then, early in his senior season, in September 2012, news broke that his grandmother and his girlfriend had died on the same day. While his 72-year-old grandmother had succumbed to natural causes, “his 22-year-old girlfriend, Stanford student Lennay Kekua, died of leukemia just eight months after surviving a life-threatening car accident,” ESPN reported at the time.

Te’o didn’t miss a game. Instead, he led Notre Dame to the national championship game and was a finalist for the Heisman Trophy, which is awarded to the country’s best player — all while grieving in public, breaking into tears on the sideline and at campus pep rallies. The day after his girlfriend’s death, he tweeted, “I may not hear your voice but I do feel your presence.” After his game later that week, he told ABC’s Heather Cox, “They were with me. I couldn’t do it without them.” His perseverance through tragedy became an inspiration to millions, transcending the sports pages and elevating Te’o into a cultural icon anybody with a functioning heart could get behind.

You know the rest. Maybe you partook in the memes. Maybe you remember the Saturday Night Live skit. A Deadspin report a week after the final game of Te’o’s college career revealed that the dead girlfriend at the center of his skyrocketing fame was actually a 22-year-old who was reported to be a man and who had spent years posing as Lennay while communicating with Te’o through Facebook messages, emails, and phone calls. They had never met face to face. In a matter of minutes, Manti Te’o transformed from a universally beloved symbol of resilience into a universally derided laughingstock.

Looking back now, it almost feels as if Te’o is frozen in time, forever defined as the first high-profile catfishing victim, the main character of a landmark internet moment, eternally trapped in the amber of 2013. Maybe only the most committed football fans are even aware that Te’o went on to play seven years in the NFL, a notable success in a league where the average career lasts less than half that long. (He’s currently a free agent looking to catch on with a team this season.) “Manti Te’o?” you might’ve said when you saw this story, taking a deep drag from your cigarette. “Haven’t heard that name in years.” If he crossed your mind at all, it might’ve been only to wonder how anyone could possibly move on with their life after going through such a cringeworthy ordeal.

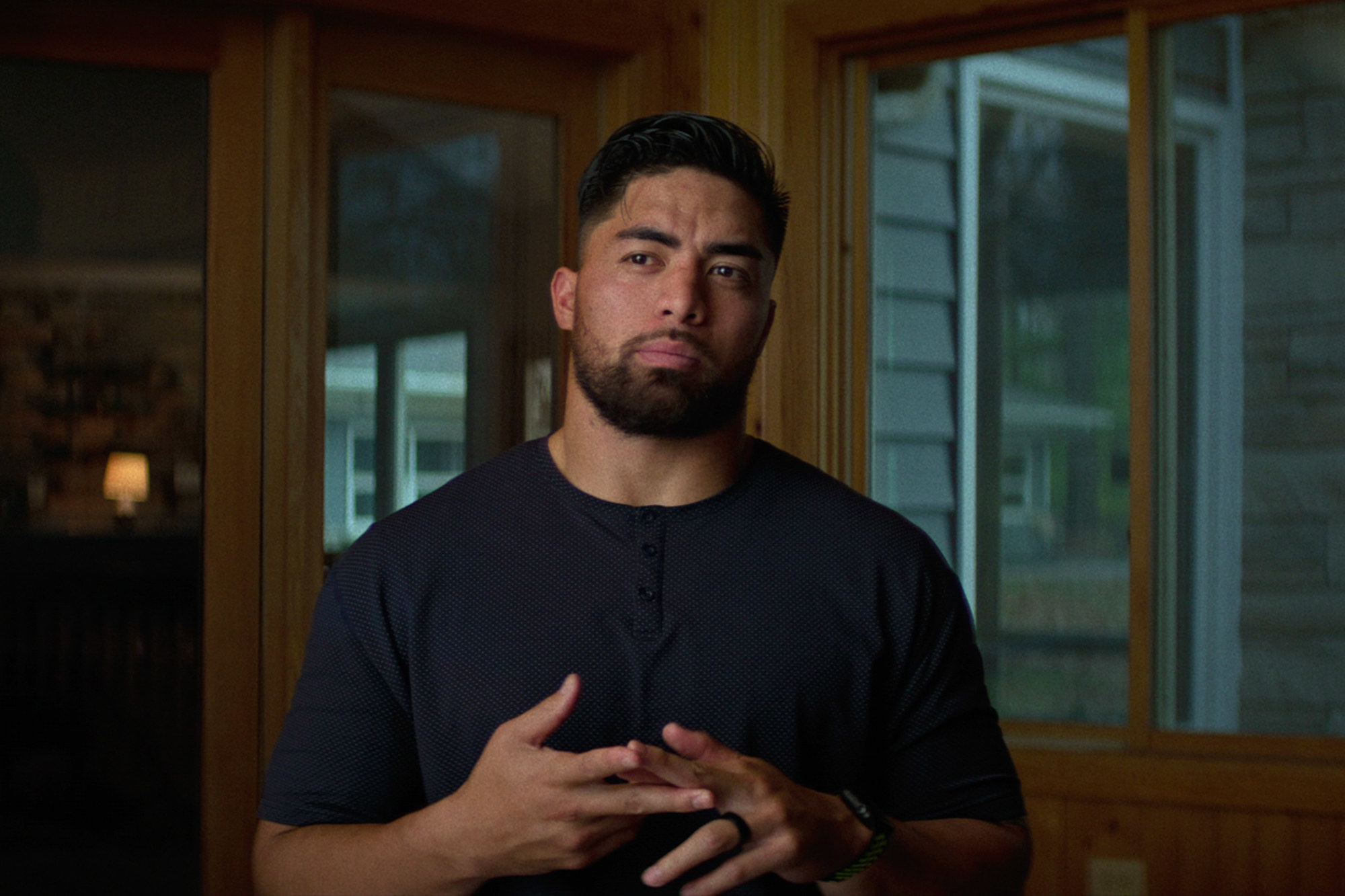

After having nearly a decade to treat wounds and sharpen hindsight, it feels like the right time for the deep-dive retrospective dropping on Aug. 16 on Netflix. Untold, a sports documentary series, opens its second season with a two-part episode focusing on the Te’o saga, titled “The Girlfriend Who Didn't Exist.” The documentary gives the most complete picture yet of what happened behind the scenes of a mesmerizing scandal that came to define a certain moment in time. A critical mass of people suddenly realized that the internet was not an imaginary place detached from reality but was, in fact, a primary vessel for reality itself.

Untold gives us what we’ve come to expect in this golden age of sports docs, approaching the standard 30 for 30 set around the time Te’o was still in college. We see the Shakespearean rise and fall, with archival footage and talking heads setting the context, and most critically, we get the main characters themselves walking us through their perspectives.

Te’o explains how he could have possibly dated a girl for three years without meeting her in person — and it makes more sense once you hear about how naive and tunnel-visioned he was, your classic goody-goody team captain who just wanted to play football, take care of his family, and praise God. This was a kid who had dreamed of going to the University of Southern California for years, only to switch to Notre Dame at the last minute because a school adviser suggested it and Te’o thought it was a sign from the Almighty. He regretted the decision almost immediately, calling his father from cold-ass Indiana to say he thought he’d made a mistake. He was very far from Hawaii, where he grew up, and was now stuck at a very Catholic school where few people shared his Mormon faith and even fewer people looked like him. He was lonely, and that was part of what attracted him to Lennay, whose Facebook profile showed that she was a fellow Polynesian with more than a few mutual friends. Te’o said he hadn’t even heard the term “catfish” yet. The MTV show was halfway through its first season at that point.

One of its early viewers, though, was the person pretending to be Lennay, Naya Tuiasosopo, who tells us that she used tactics she saw on Catfish to get around Te’o’s requests to video chat or meet in person. Naya is a trans woman, and the events we’re looking back on took place before her transition, when she was grappling with “something inside of me that just wanted to scream, ‘Why am I different?’” She found comfort in the Facebook profile that allowed her to be who she felt she was — “an escape where I felt safe,” she says in the film.

While Untold lets the principals speak for themselves, it leaves its most critical judgment for the media circus that erupted, which was uncomfortable at the time and has aged all the worse. There’s Dr. Phil in January 2013 asking Naya to prove she could replicate the high-pitched voice she used with Te’o because his experts said it was almost impossible for the voice in Te’o’s voicemails to belong to the young man she then presented as. There’s Katie Couric asking Te’o if he’s gay, because there was a theory going around on cable news and social media that he’d helped orchestrate the scheme to cover up his sexuality from his socially conservative community.

Lost in the messy details that absorbed our attention was the fundamental reality that this saga began as a tale about two teens in love.

While the bulk of the documentary presents an in-depth version of the story we’re familiar with, its most compelling new material chronicles the aftermath. At its core, this is a story about two young people healing from the damage of experiences the rest of us are only beginning to understand.

After everything went down, Naya went to American Samoa, where she found an LGBTQ community that helped her feel comfortable transitioning. She was so removed from public view that nobody else in the film has any idea what her life has been like in recent years. Early on, the documentary provides a disclosure noting that its interview subjects misgender her and refer to her by her deadname because they weren’t aware she is trans. This unfortunate complication neuters some of the potency from the film’s heartfelt final moment; Te’o forgives Naya, but doesn't use the correct pronouns.

That show of grace offers a useful resolution to the story, but it’s clear the emotions are still raw, the process ongoing. Naya speaks about Te’o with the tenderness befitting an ex you still have love for. Te’o’s voice catches and he starts to cry when he tries to talk about the moment he found out that Lennay had died. Lost in the messy details that absorbed our attention was the fundamental reality that this saga began as a tale about two teens in love and ended with their three-year relationship shattering suddenly and traumatically. Whatever might have been fake about it, the feelings were as real as can be.

With news cameras swarming, the life-changing money of a professional football career on the line, and his golden reputation shredded into a heap of mockery, 21-year-old Te’o was left to unpack the realization that his most serious adolescent romance was with a man, grappling with a worldview shaped in a generation that grew up using “gay” as a generic slur, a sport that prized hypermasculinity, and a religious faith that didn’t recognize marriage for same-sex couples.

For Te’o, months of mourning his grandmother and girlfriend were immediately followed by months of being the subject of one of the most embarrassing public spectacles in recent memory, one that ultimately cost him millions of dollars because it seemed to contribute to him getting selected later in the NFL Draft.

He became famous beyond the sports page for his displays of emotional resilience, only to become infamous for an incident that tested that emotional resilience.

We are familiar with people persevering through certain kinds of tragedies. An athlete's loved one dies and they play in their honor, inspiring all. In high school, Chris Paul scored 61 points after his 61-year-old grandfather died. With “RIP Sis” scrawled in marker on his sneakers, Isaiah Thomas scored 33 points in a playoff game the night after his sister died in a car crash. Brett Favre threw for 399 yards and four touchdowns the day after his dad died. Many other such performances are etched into sporting lore.

Those stories are moving, and we like them because we all have loved ones die and must manage to move forward. Te’o was the latest in a long line of tropes, playing through the grief with a sacred purpose. He might have never been through something like that before, but he had seen others go through it, and he knew how he was supposed to carry himself, what he was supposed to do, how to properly honor them.

But there was no script for what came next. “I didn’t know who to talk to,” Te’o says in the doc, explaining that he did whatever his crisis management consultants advised. “Honestly, I didn’t wanna say anything.” It was such a big story because we had never seen such a thing at such a scale. Dude was in uncharted waters. This wasn’t about persevering in the wake of tragedy, or asking for forgiveness after immoral acts, or rebranding a persona associated with a toxic reputation. This was about getting clowned pure and simple, your most embarrassing experience broadcast for everybody to see on the biggest stage, a show starring you but the jokes are on you, all happening back when we were so enthusiastic and relentless and extra snarky on the internet, when those mass pile-ons still felt novel, maybe even harmless.

Months after the initial news cycle, when he took the field for his rookie season with the San Diego Chargers in late summer 2013, he found himself so wracked with anxiety, “my feet just started to go numb,” he says, “and it slowly went up my legs till everything was tingling.” Once a player who moved freely, joyfully, and full of confidence on the field, now he was “questioning everything,” he says, begging himself, “Don’t mess up, bro. Just please make a play today.” How could he trust the same judgment that had taken him down such a foolish path? The tingling sensations persisted for three years, he says, until he began to see a therapist who helped him process the hardest period of his life.

I’m not going to sit here and tell you that being a target of public ridicule is harder than losing a loved one. But Te’o processed one traumatic event with the world cheering him on, then the next as the butt of everyone's jokes. And now here he is living to tell the tale, a survival story from the darkest depths of internet humiliation, a parable on the virtue of fighting the bitterness threatening to consume him “no matter how hard it is for me,” he says.

His spiral into pariah status seems disorienting now, after all the various depravities we’ve witnessed over the last decade.

“Treat ’em nice in a world that’s just spit on you,” he says near the end of the doc. “I’ll take all this crap. I’ll take all the jokes. I’ll take all the memes. So I can be an inspiration to one who needs me to be. That’s the whole reason why I’m doing this.”

If you’re cynical, maybe you see this as a calculated ploy by a 31-year-old fringe NFL player trying to position himself for the lucrative opportunities that come to retired athletes who sound interesting on camera. With his playing days numbered, what better time to resurrect the brand so many of us fell in love with once upon a time?

But I believe him. I want him to inspire me again. Where was I when I learned Manti Te’o got catfished? Sitting in my living room in San Francisco in a downtrodden daze, a longtime fan watching my hero fall in a cascade of ridicule. I was four years removed from the end of my own college football career, and I saw in Manti a version of me in a parallel universe where my gridiron dreams are realized. Manti is two years younger than me, and he looked more like me than any high-profile football player I’d ever seen. I’m half-Filipino and he’s Samoan, but you don’t see a lot of Pacific Islanders on the field who aren’t ginormous 300-pound titans. Manti was a smooth athlete, fast and graceful, with a sick half-sleeve tat and a corny, good kid vibe that matched a persona I had once carried, before I quit the straight-edge football life and became a full-time heathen. Unlike me, he was talented enough to get recruited by Notre Dame, the college I’d wanted to play for so badly that I mailed the coach my high school highlight tape on VHS and a flowery letter expressing my dedication. Though I’d never met him, I thought of Manti like a little brother who learned from my shortcomings and stayed true to paths I’d strayed from, and when things crashed down, I felt his pain as my own.

In the doc, Te’o says that before everything changed, when he’d enter a room, people would say “That’s Manti Te’o!” and greet him enthusiastically; after the spectacle, they’d avoid eye contact and whisper to one another, “Hey, that’s Manti Te’o. That’s the guy that got catfished.”

His spiral into pariah status seems disorienting now, after all the various depravities we’ve witnessed over the last decade, after so many women have come forward with reports of sexual assault and domestic violence at the hands of football players. Maybe if Te’o’s professional career had brought a new slate of athletic feats impressive enough to replace the old memories, his moment of viral infamy would feel like a distant prologue rather than the first thing people think about him. But that logic of populist redemption is what has led thousands of people to purchase the jerseys of accused rapists and woman beaters, celebrate their success, and presumably extend mercy for their alleged sins.

The way Te’o sees it, his redemption can only come from within. He found the first steps in that direction, he says, when his therapist asked him a question he had never considered: “Have you forgiven yourself?” ●