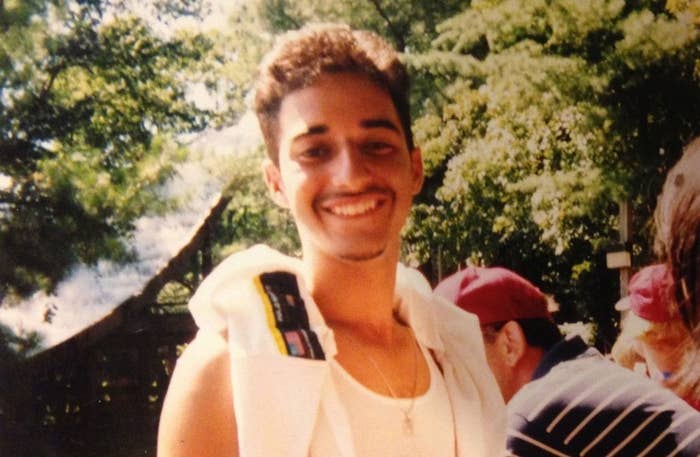

Fifteen years after Adnan Syed was convicted for the murder of his ex-girlfriend Hae Min Lee, the case became the basis for an immensely popular podcast, the This American Life spin-off Serial. Syed's classmate Jay Wilds, who said at trial that he helped Syed bury Lee's body, became the central figure in the national conversation over Syed's guilt. Wilds never spoke on tape with Serial's host, Sarah Koenig, but after the podcast's final episode, he granted an interview to The Intercept, published in three parts last week.

In the interview, Wilds told a story that differed from the one he told police and jurors, and for a while, it seemed that the story of Serial — which ended with Koenig admitting that she wasn't convinced of Syed's guilt or innocence — could end with Syed going free after all.

Unfortunately for Syed, it's not that simple. Here's what happened, and why, barring further developments, the case against Syed will likely still stand.

Jay’s Account to The Intercept Is Different From His Testimony

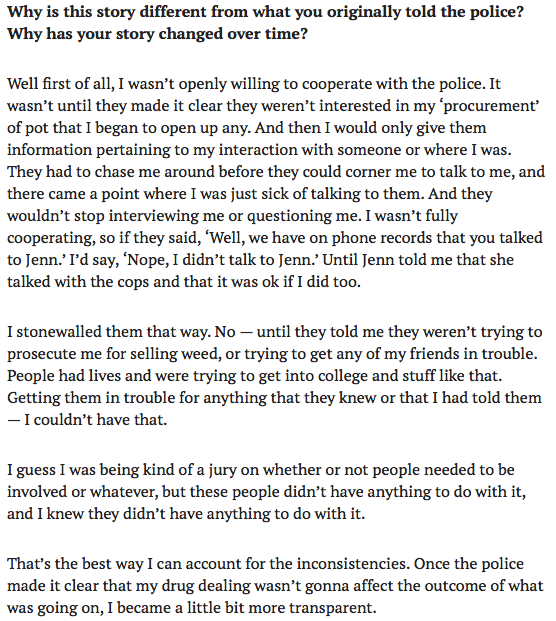

After the Intercept interview, it seemed like the most important witness in the state's case had undermined his own credibility. He admitted lying to the police when he first talked to them, lying in the testimony he gave at trial, lying about what he and Syed did on the day of the murder, lying about where he first saw Lee's body, and lying about what time they went to Leakin Park to bury the body. Wilds also admitted to lying about other details. From the interview:

People Started Wondering If That Meant Syed Might Go Free

"[I]n terms of whether Adnan should be in jail right now, the question is whether his guilt is beyond a reasonable doubt. And it's hard to imagine, right now, how anyone could be free of doubt about Jay's testimony," Vox's Ezra Klein wrote in an article headlined "Jay's Interview Shreds the Case Against Adnan Syed."

"Jay From 'Serial' Gave An Interview That Might Actually Help Adnan Syed," read a headline on this website.

"Nearly 15 years ago, the prosecution argued to the jury that it should ignore the 'inconsistencies' in Wilds' statements — that the 'spine' of his story remained the same," Rabia Chaudry, Syed's main advocate, wrote in The Guardian. "But with his interview yesterday, Wilds broke that spine, and possibly the state's case with it."

But the Legal Standard Is Different When It Comes to Overturning a Conviction Than It Is Obtaining One

After the guilty verdict, the burden of proof flips to the accused.

"Once a person has been convicted at trial he is no longer presumed innocent," Brandon Garrett, a University of Virginia law professor who serves on the advisory board for the National Registry of Exonerations, told BuzzFeed News. "Because courts are deferential to that finding of guilt, the evidence that was used to convict the person tends to be presumed correct."

That is especially the case when a witness changes his story years later. Memories fade, motives change.

"The court views recantation evidence with great suspicion," said Steve Drizin, a law professor at Northwestern University and an attorney at the Center for Wrongful Convictions, who considers the court's view on this flawed. "In part because they occur later in time than the original testimony, and because they are going up against testimony that was under oath."

And Wilds did not outright recant. He changed his timeline, and many details, and offered an explanation for his lies (his fear of implicating his grandmother and friends; his fear of getting busted for selling drugs). But the most important points remained (what the prosecution called the "spine" of the case against Syed): Syed called Wilds that afternoon, Wilds saw the body in the trunk, and Wilds helped bury the body in the park.

Syed's legal team might point out that, whether he was lying in 1999 or lying in 2014, the fact is that Wilds is a liar, and that should cast doubt on Syed's conviction. But that does not mean there is enough doubt to overturn a conviction.

Overturning Convictions Is Very Hard

After a person is convicted, guilt beyond reasonable doubt is out the window. The standard of proof a person must meet to get a conviction overturned is higher than the standard he must meet to get an acquittal.

To persuade a judge to grant a new trial, an appellant must show that there is a "reasonable probability" — the exact language varies by state and on the specific legal maneuver — that the outcome would have been different if the new evidence had been included in the original trial.

Often, this means that the new evidence is "noncumulative," that it doesn't simply bulk up evidence already established at trial. A judge must consider, "Do these additional problems really add anything to the case?" said Drizin.

This is why Wilds' Intercept interview might not matter at all in Syed's legal efforts. Wilds' credibility was already in question at trial. The jury knew he had lied to police and heard the inconsistencies in his story, and chose to believe him anyway.

The determination of how much new evidence is enough to merit a new trial falls under the full discretion of the judge, which doesn't usually bode well for the appellant.

"Judges may put a finger on the scale against do-overs," said Garrett. "They don't like to order do-overs of trials. They like to do it right the first time."

There Are Lots of People in Prison Under Similar Circumstances

For every proven wrongful conviction, there are hundreds more where the truth is not so clear and the burden is of proof is too high. That may be the case for Syed, and if it is, it will be an instructive case.

"The Serial case doesn't look particularly unusual," said Garrett. "It looks like lots and lots and lots of violent crime cases where the main witnesses are cooperating witnesses and there are no eye witnesses to the violent act, where guilt has to be proven circumstantially. Maybe it's a good thing that people are introduced to this fact of life in the criminal justice system. For people who want closure, there may not be closure."