NEW ORLEANS, Louisiana — The courthouse at his back and the rain about to fall, William Varnado bummed a half-smoked cigarette from a stranger.

“Desperate times,” the 36-year-old Varnado said, half-joking as he brought the cigarette to his lips. Smoke curled out his mouth, snaking toward the overcast New Orleans sky, as he spoke of the guilt that had haunted him for years.

He was now free of that guilt, he said on this February morning. It no longer ambushed him in nightmares or lingered in his mind during waking hours like a stubborn stench. The guilt, he said, had been replaced by fear.

In 2000, Varnado testified in the murder trial of Duvander Hurst, a man he had known since his childhood in the city’s Hollygrove neighborhood. The only eyewitness to take the stand, Varnado identified Hurst as the gunman in a high-profile killing outside the Superdome. With no physical evidence linking Hurst to the crime, the trial hinged on Varnado’s statements. Hurst was convicted and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Hurst went on to Angola prison. Varnado went on with his life. He moved to Houston, worked as a barber and a cook, and settled in with his girlfriend, their daughter, and his girlfriend’s four children. They lived in a five-bedroom house and made wedding plans. But the better his life got, the more the guilt grew until one day he could no longer stand it.

“I felt like I didn’t deserve the life that I was living,” he said. “Because I took somebody else’s life.”

And so, he said, he came clean: He had lied in his testimony, he declared in a 2013 affidavit. He had been a heroin addict, gotten arrested for drug possession, and faced prison time. The understanding was that he could go free if he helped out on the Superdome murder case. The detective told him what to say and he repeated it, all the way through trial. “At that time I was strung out on heroin and I was willing to do anything to get back out of police custody and back on the streets,” Varnado stated in the affidavit. “The truth is I was never at the Superdome” the night of the murder.

But instead of investigating this claim that police coercion may have sent an innocent man to prison, Orleans Parish District Attorney Leon Cannizzaro charged Varnado with perjury in August 2016. He faces up to 40 years in prison if convicted.

These perjury charges are “intended to put a chilling effect on people coming clean.”

It was the third time in two years that Cannizzaro had filed perjury charges against a witness recanting testimony from an old murder conviction. In 2014 Cannizzaro charged two men who recanted testimony they gave as teenagers in a murder trial in the early ’90s. After speaking with dozens of legal experts and contacting attorneys at every Innocence Project office in the country, BuzzFeed News could not find any other prosecutor in America with more than one such case. More than a dozen lawyers who spoke to BuzzFeed News about this story called Cannizzaro’s use of perjury charges troubling and unconventional. (Cannizzaro’s office did not respond to several interview requests for this story.)

These perjury charges are “intended to put a chilling effect on people coming clean,” said New Orleans City Council Member Jason Williams, a defense lawyer by trade. “They’re basically saying, ‘If you look into what we’re doing, if you meddle in the business of our prosecutions, we will use our power against you.’”

At a time when prosecutors across the country are acknowledging and reviewing the mistakes wrought by policies born in the ’80s and ’90s, Cannizzaro’s decision to go after recanting witnesses reflects the lingering resistance to rethinking the past. “It’s a denial that those days were as bad as they were,” Williams said.

It’s a denial that stretches to the highest level of government, to the president and the attorney general, who have vowed to expand law enforcement freedoms and protections to counter the “American carnage,” as President Donald Trump described the state of violent crime in his inaugural address. This platform is built on a fictional premise: 2015 had the third-lowest violent-crime rate of any year since 1970, according to FBI statistics. (Complete 2016 data is not yet available.)

Varnado stubbed out his cigarette on the sidewalk at the base of the Orleans Parish Criminal District Courthouse. He had attended a pretrial hearing that morning. The massive, grime-stained stone building towered over him, a fitting symbol for the city with the highest incarceration rate in the state with the highest incarceration rate in the country with the highest incarceration rate in the world.

He shook his head in frustration, then loosened the necktie he had worn for the occasion and pulled the loop off his head. He was ready to leave this place.

“This whole system feels like it’s designed to keep Duvander in prison and get me in there with him,” he said. “It’s like they’re trying to punish me for telling the truth.”

The first thing most recanting witnesses ask is: “Will I get in trouble?”

The typical answer, according to more than a dozen lawyers who specialize in appeals, has been: “It’s possible, but probably not.”

“The legal advice I’ve given is that nobody has even been prosecuted in those cases,” said Rob Warden, co-founder of the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University. “But, well, in view of what’s going on in Louisiana, that’s not true anymore. You can’t tell somebody that anymore.”

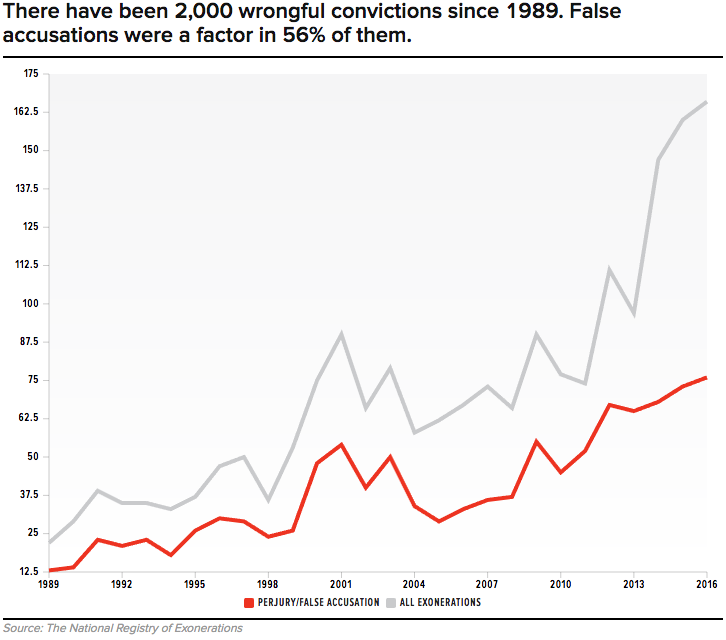

Since 1989, the year DNA evidence first exposed a wrongful conviction, around 2,000 people have been exonerated, according to the National Registry of Exonerations. A false accusation was the sole cause of more than 10% of those convictions and a contributing factor in more than half. And the deluge of exonerations shows no sign of slowing: There were 166 in 2016, the most in a single year, breaking the record set in 2015, which broke the previous record set in 2014.

Twenty-one states have laws that partially protect witnesses whose recantations come at least two to five years after their original statement. Legislators have pushed similar bills in other states.

Yet with or without such laws, the fate of recanting witnesses lies with prosecutors. Collectively the most powerful force in the criminal justice system, district attorneys decide which laws to apply, how to apply them, and who to apply them against.

The first thing most recanting witnesses ask is: “Will I get in trouble?”

“Nobody should ever be prosecuted for a recantation absent evidence the recantation is false,” said Warden. “My fear is that this is a very serious problem if it is copied elsewhere. As the number of cases with untested DNA evidence dwindles down, recantations are going to be extremely important.”

Before Cannizzaro, the last prosecutor to pursue perjury charges against a recanting witness was Anita Alvarez, former state’s attorney of Cook County, which encompasses Chicago. In 2011, Alvarez filed a perjury charge against Willie Johnson, who recanted his testimony identifying the shooter in a 1992 murder. Johnson pleaded guilty and was sentenced to two and a half years in prison, but Governor Pat Quinn commuted the sentence.

The threat of perjury charges is enough to discourage some witnesses from recanting.

One of the most startling examples of this came in 2008, when William Avery took the stand in a hearing over the possible wrongful conviction of Alfred Cleveland. Avery had previously testified that Cleveland was involved in a 1991 murder in Lorain, Ohio. In 2006, he signed an affidavit stating that he had lied for the reward money.

Just as Avery was about to tell the courtroom about his recantation, the judge warned him that he could face perjury charges if he admitted to lying under oath. Minutes later, after speaking to a lawyer, Avery changed his mind and refused to testify. As he left the witness stand, he passed Cleveland, whose wife was in the audience crying.

“Please, man,” Cleveland said. “Please, man.”

Avery later explained his decision to the Columbus Chronicle-Telegram:

“Dude’s innocent,” he said. “But I don’t feel I have to go to jail for 30 years.”

The Orleans Parish Criminal District Courthouse has been Leon Cannizzaro’s domain for decades.

The son of a shoe salesman and a cashier, Cannizzaro has spent his life in New Orleans. He went to the University of New Orleans, studied law at Loyola University, then began his career as an assistant district attorney in the DA’s office, where he worked five years, climbing to chief of the trials division.

He became a criminal court judge in 1986, at the dawn of America’s crime surge. Cities across the country experienced record-high violent crime rates over the next decade, but few had it as rough as New Orleans. In 1985, the city's murder rate stood at 27 per 100,000 residents — higher than in New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago, and nearly three times higher than in Milwaukee, a city of similar size. That number doubled within five years and tripled within a decade, peaking in the mid-’90s, when New Orleans had the nation’s highest murder rate for three straight years.

Many states responded to rising crime with laws that lengthened sentences and sent more nonviolent offenders to prison. For public officials, compassion for criminal offenders was not something to boast about at a time when many Americans were clamoring for more aggressive law enforcement. In this tough-on-crime era, Louisiana became the toughest, setting off a wave of incarceration that would continue for decades, exceeding the pace of every other state.

From 1974 to 2004, under the three-decade reign of District Attorney Harry Connick, New Orleans’ jail population jumped from 800 to 8,500, even as its overall population dropped from 570,000 to 460,000. A disproportionate number of these inmates were, like Duvander Hurst, black men. By 2005, 13 of every 1,000 residents in New Orleans were in jail, more than four times the national average. According to a 2012 New Orleans Times-Picayune investigation, more than 300 inmates in Louisiana were serving life without parole even though they hadn’t been convicted of a violent offense.

So the ’80s and ’90s were particularly busy years in the Orleans Parish Criminal District Courthouse. By Cannizzaro’s own accounting, he presided over more jury trials than any judge in state history, sometimes completing more than one trial in a day. His single-minded focus forged in him an inflexibility that would earn him both admiration and animosity. One local defense attorney capped off a diatribe against Cannizzaro by adding, with a grin, “but I like the guy.” The city’s Metropolitan Crime Commission named Cannizzaro “Top Overall Performing Judge.” His peers on the bench appointed him chief judge of the criminal court.

Since 2001, 32 people have been exonerated in Louisiana. Around 75% of the state's wrongful convictions involved misconduct by police or prosecutors.

By the late ’90s, the nation’s crime rate had begun its dramatic decline, a trajectory that continues to this day. Even as the streets turned safer, tough-on-crime philosophies persisted in many cities, including New Orleans. In 2001, the city’s murder rate was nearly half of what it had been seven years earlier. The next year, in his campaign for a seat on the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals, Cannizzaro distributed signs that deemed him “America’s Toughest Judge.” He won the election.

By then, the costs of the tough-on-crime era were becoming clear. Since 2001, 32 people have been exonerated in Louisiana. All but one were convicted between 1976 and 1999. According to data collected by the National Registry of Exonerations, around 75% of Louisiana’s wrongful convictions involved misconduct by police or prosecutors; the national rate is 51%.

The case files of wrongful convictions in New Orleans show a law enforcement apparatus whose tactics were, at best, sloppy, and, at worst, intentionally deceptive. In 2010, after New Orleans police officers shot 27 black men in 17 months, the Department of Justice opened an investigation into the NOPD for the second time in less than two decades. Some of the review’s most damning findings concerned how the department built its criminal cases. Federal investigators discovered that officers didn’t record entire interrogations, didn’t keep their interview notes, “misrepresented witness statements,” and failed “to investigate allegations of planting evidence.”

“The NOPD has long been a troubled agency,” a DOJ report stated.

This was the law enforcement culture cemented in the tough-on-crime era and maintained in the years that followed. It was the culture in place on June 7, 1999, when 19-year-old Allen Galathe was shot dead outside the Superdome.

Nine days later, on June 16, 1999, William Varnado was arrested for possession of crack cocaine. It was his second drug arrest in 13 months. A year earlier he had been convicted of heroin possession and entered a diversion program for first-time offenders. Now, as he sat handcuffed in the back of the police car, the 18-year-old faced a decade or more in prison.

Varnado’s block, all bright clapboard houses on cinder block stilts, was a few hundred yards from where Duvander Hurst lived in the city’s Pigeon Town neighborhood, a stretch of sleepy porch-lined streets that pushes up against the Mississippi River. Varnado did not know Hurst well, but he was close with his younger brother and cousin. They played little league football together.

Now Hurst was the prime suspect in the Allen Galathe homicide case. As Varnado was being arrested, the officer asked: Do you know anything about the Superdome murder?

Everybody in the city had heard about the Superdome murder. The shooting had occurred just after the Super Fair, an annual carnival held at the stadium, as hundreds of people spilled out into the humid night. The police said that witnesses saw the shooter step out of a red Oldsmobile Cutlass. Hurst, who was 19 and had a gun possession conviction as a minor, owned a red Oldsmobile Cutlass. News cameras were outside his mother’s house a day after the shooting.

Varnado agreed to talk about the Superdome murder, and when they arrived at the police station, the officer dropped him off in an interrogation room. There, Varnado met Detective Archie Kaufman, a highly respected veteran investigator often assigned to the city’s biggest homicide cases.

Years later, Kaufman would gain national infamy and serve three years in prison for orchestrating the cover-up after officers fatally shot two unarmed black people, and wounded four more, on the Danziger Bridge a few days after Hurricane Katrina.

Back in 1999, though, Kaufman was best known for closing cases. His work on the Superdome murder only seemed to further that reputation. He left the interrogation room with a signed statement from William Varnado identifying Hurst as the shooter.

In exchange, Varnado was allowed to remain in the diversion program despite his second drug offense, and he was back on the streets within a couple of weeks.

Outside of Varnado’s testimony, prosecutors had a weak case. A police report stated that two witnesses at the scene claimed the shooter was “Chevy,” which was Hurst’s nickname. But police did not take follow-up statements from them and they weren’t called to testify. No murder weapon was found. No DNA, fingerprints, or other forensic evidence linked Hurst to the crime. As for the red Oldsmobile Cutlass? Hurst had taken his to a body shop after getting into a car wreck on June 3, four days before the shooting. The mechanic had the receipt. The car was still at the shop when police arrived to inspect it after arresting Hurst — prosecutors argued that Hurst must have used a spare key to drive off with his car before returning it after the murder.

All prosecutors really had was the man they claimed was their sole eyewitness — Varnado.

The jury deliberated for half a day before returning with a guilty verdict. Varnado walked home. He feared that his testimony made him a target in his neighborhood. The next day, he boarded a bus to Houston, then checked into a rehab program.

He had no plans to ever return to New Orleans.

In August 2005, Hurricane Katrina knocked the city’s criminal justice system into chaos. There wouldn’t be a trial in New Orleans for almost a year. Suspects facing minor charges were stuck behind bars for months, for no reason other than being in jail on the day the storm hit. Judges, dressed in T-shirts and shorts because most of their clothes remained at their evacuated homes, held court hearings in a bus terminal. Evacuating the flooded jail, the sheriff’s office shipped inmates to facilities across the state, a process so haphazard and rushed that many lawyers had no idea where to find their clients. The backlog of cases built up.

In 2007, the city’s murder rate hit an all-time high, higher even than in the ’90s and double the rate of the city in second place that year, St. Louis.

The way some local lawyers and city officials remember it, Leon Cannizzaro rode in as a savior. Upon taking office in 2009, Cannizzaro went about reforming flaws he saw in the court system. He switched marijuana offenses to municipal court, to ease the backlog of criminal cases. He moved domestic violence cases out of municipal court and into criminal court in an effort to better support victims. He cut down the time suspects waited in jail before arraignment. He rebuilt his office’s relationship with the police department, which had grown frustrated that his predecessor, Eddie Jordan, prosecuted barely half of the cases detectives brought to him, citing a lack of evidence. Within a few years under Cannizzaro, the DA’s office was accepting more than 90% of cases while maintaining a conviction rate above 80%, higher than in most other big jurisdictions.

“He’s a systems guy who made the office and the courthouse more efficient,” said Emily Maw, director of Innocence Project New Orleans, which reviews questionable convictions of the past. “People had high hopes for him right away.”

Longtime local attorneys and city officials said Cannizzaro was much more hands-on than any previous DA they had worked with. By the end of his first six-year term, the city’s murder rate had dropped to pre-Katrina levels, putting the city roughly back on track with the national crime decline.

But the past haunted the DA’s office. Cannizzaro had inherited at least a dozen solid claims of wrongful conviction, as well as the lawsuits filed against the office by recent exonerees locked up by his predecessors. In one case, a civil jury awarded $14 million to John Thompson, who spent 18 years imprisoned for murder and robbery before his exoneration in 2003. In its verdict, the jury blamed systemic problems within the DA’s office, including “deliberate indifference” to the rights of the accused. At least one prosecutor had withheld blood test results, witness statements, and police reports that proved Thompson’s innocence.

Cannizzaro appealed the case all the way to the US Supreme Court, which in 2011 rejected the earlier verdict in a 5-4 vote, denying institutional wrongdoing and instead blaming the single prosecutor.

Thompson would get nothing, and the ruling established that the DA's office would only be liable if there was proof of systemic misconduct. Cannizzaro told reporters the ruling had removed a “dark cloud of uncertainty that was hanging over the district attorney's office.”

Two years later, his office received the written recantation of William Varnado.

Duvander Hurst worried that Varnado would back out. How could he trust the man who had put him in prison? Named for the plantation it replaced, Angola sprawls across farmland tucked between woods and river, more than a hundred miles from New Orleans. As a kid in that city, Hurst spent his free days catfish hunting and playing football. As a teenager, he mowed lawns and worked construction, jobs that once filled him with dread but now filled him with nostalgia.

Hurst had professed his innocence from the start. Now, his fate was in Varnado’s hands once again. Just as Varnado’s testimony was the centerpiece of the murder case, his recantation was the basis of the appeal.

“They doing the same thing they did to him 16 years ago: try to scare him,” Hurst said. “I just pray to God he stay strong.”

Over the years, news of exonerations passed through Angola’s cellblocks. “I was jealous, but I was happy at the same time,” Hurst said. “It’s a dream to see somebody walk out these gates, ‘cause every day you see somebody die.”

During Hurst’s time in prison, major policy changes swept through DA’s offices across the country. Within the last decade, more and more prosecutors have made efforts to hold police officers accountable for wrongdoing, to minimize the number of nonviolent offenders sent to prison, to limit the number of juveniles locked up in adult facilities, and to review the possible mistakes of their predecessors.

The same election cycle that sent Trump to the White House knocked off tough-on-crime incumbents in Chicago, Cleveland, Houston, Jacksonville, Orlando, Tampa, Birmingham, and northern Mississippi. DAs who campaigned on reformist agendas, some of whom received hefty campaign contributions, also won office in St. Louis and central Georgia in 2016 and, over the previous three years, in Brooklyn and Caddo Parish, Louisiana.

In 2014, Cannizzaro announced a “conviction integrity unit” to review old cases in partnership with the Innocence Project New Orleans. The unit shut down after one year.

Leon Cannizzaro, though, has hung on, battling a city council that in recent years criticized his tough-on-crime approach. Even when he seemed to open himself up to fixing the collateral damage of the past, critics said, he did so half-heartedly.

In 2014, Cannizzaro announced that his office would establish a “conviction integrity unit” to review old cases in partnership with the Innocence Project New Orleans. The City Council increased his budget by $250,000. According to the National Registry of Exonerations, New Orleans has the highest per capita rate of proven wrongful convictions. Cannizzaro’s newfound interest in the subject was big enough news to make the front page of the city’s newspapers.

The unit shut down after one year.

Cannizzaro’s office told the New Orleans Advocate that the City Council cut the funding. But council members Susan Guidry and Jason Williams, and Innocence Project New Orleans director Emily Maw, said the partnership ended because Cannizzaro wouldn’t work with Maw’s staff.

“It clearly wasn’t a priority for him,” Maw said. “His office didn’t handle the cases any different from before and didn’t seem interested in changing.”

Maw cited the case of Jerome Morgan. Based on the 1994 testimony of two teenage eyewitnesses, Morgan was convicted of murdering 16-year-old Clarence Landry at a birthday party. Twenty years later, the two witnesses, Hakim Shabazz and Kevin Johnson, recanted their statements. Like Varnado, they said that police had pressured them to identify Morgan as the shooter.

After Morgan was freed, the prosecutor filed perjury charges against Shabazz and Johnson.

“What I do know for certain is that Johnson and Shabazz either perjured themselves in 2013 to allow a cold-blooded murderer to walk free, or they perjured themselves in 1994 to put an innocent man in jail,” Cannizzaro said in a statement to the press. “Either way, they deserve to be punished.”

A judge acquitted both men in January 2017.

In Houston after the Hurst trial, Varnado stayed in rehab and eventually got his life on track. There was no Road-to-Damascus moment — he had tried several times, and this particular attempt worked out better than previous ones. He found work as a cook and a barber. He fell in love and had his family. He saw his future laid out before him.

Then Katrina hit. Thousands of New Orleans residents migrated to Houston. One day, Varnado saw one of Hurst’s cousins in a convenience store. The cousin didn’t notice him, he said, but just the sight of the man sent waves of shame and sadness through him. “I knew that I had to fix it,” he said.

"I don’t wanna be the reason Duvander was in prison for the rest of his life."

He told his girlfriend everything. He said that he wanted to admit his lie. His girlfriend told him to put his family first and forget about this case. She worried he might get in trouble for the lies. And, after all, he didn’t even know if Hurst was actually innocent.

“Maybe he did it, maybe he didn’t. But I don’t know if he was guilty. I never knew. And I don’t wanna be the reason Duvander was in prison for the rest of his life,” Varnado said.

Through friends, he tracked down Hurst’s younger cousin, the one he played football with. The cousin put Varnado in touch with Hurst’s mother, who had been working with a private investigator to build her son’s case for appeal.

And so, first to a private investigator and then in a 2016 court hearing, Varnado told a story different from the one he had told in 1999.

He was at home on the night of the Superdome murder, he said. “I seen it on the news like everybody else,” he said in one of several interviews with BuzzFeed News. Over the next few days, he heard more about the shooting from friends who said they were at the Super Fair that night. One friend told him that two groups of men had been fighting shortly before the shooting. Another friend said that the brawl started after somebody got jumped. “A lot of people were talking about that shooting,” he said.

Arrested for crack cocaine possession a few days later and hoping to avoid prison, “I’m trying to talk my way out of these handcuffs,” he said. “I’m like, ‘What y’all want me to do? I’ll say anything you need.’ And the officer, that’s when he asked me what do I know about the Superdome shooting.”

The officer told him their suspect was from his area of town. Did he know Duvander Hurst? He did, he said. Varnado wrote in his affidavit that the officer told him, “if you help us, we will help you.”

Varnado wrote in his affidavit that the officer told him, “if you help us, we will help you.”

In the interrogation room, “Detective Kaufman gave me a scenario to lead me into a story of what happened the night of the murder, then he started the tape recorder,” Varnado stated in the affidavit. “I replied to his scenario with a story I made up. Detective Kaufman stopped the tape and then said, ‘No. That ain’t right.’ He rewound the tape and hit record again and I then came up with another made-up version of what happened and Kaufman said, ‘Alright.’”

This went on late into the night, he said, to make sure the story was airtight and all the little details were consistent with the facts — the time of day, the color of the shooter’s car, on which side of the building the murder took place, what side of the street the car was on. “He kept going over all that until it sounded more convincing,” Varnado testified in 2016.

In his police statement in 1999, Varnado said that he was leaving the Super Fair with his girlfriend when he saw a fight break out between guys from Pigeon Town and guys from the 3rd Ward. Not long after, he said in the statement, he saw the red Cutlass pull up on Poydras Street in front of the Superdome’s main entrance, and then he saw Hurst step out and fire into a crowd.

“By the time I testified before the grand jury, I had the story down pat,” he said. “I was acting.”

As the trial neared, Varnado had second thoughts about testifying. He was worried less about the lying than about the dangers of snitching, he said. Whether or not Hurst was guilty, Varnado was slapping a target on his own back as a witness in the murder trial of a man from his part of town.

Before the trial, Varnado told Assistant District Attorney Lynda Van Davis that he did not want to testify and asked what would happen if he backed out. “I explained that the District Attorney may choose to take away his diversion and he may face prosecution for his two drug arrests,” Van Davis wrote in a 2017 court statement.

Varnado claimed that Van Davis was more direct: According to his 2016 testimony, she vowed to put him away for the full 20 years.

After he recanted, Varnado asked the private investigator, a lawyer, and some of Hurst’s relatives whether they thought he might get charged with perjury. “Everybody kinda downplayed it, man,” he said. “They said it was a possibility, but that it wasn’t something that really happened.”

In April 2016, Varnado rode a bus 19 hours to New Orleans from Texas, took the witness stand, and testified about his recantation in a hearing for Hurst’s appeal.

Four months later, on August 1, Cannizzaro charged him with perjury, which, because it involved a murder case, carries a minimum of five years and a maximum of 40 years in prison.

Two months later, he failed a court-mandated drug test and checked into rehab.

On the day of his latest court hearing, William Varnado woke up at 2:30 in the morning, as he had every day for two weeks. He worked as the cook at his rehab center and had to get breakfast ready by 5:30 a.m. He gingerly descended from the top bunk in the dormitory he shared with several other men. They hated that his alarm rang this early, but they loved that Varnado bypassed the facility's menu for his own preferences. Oatmeal breakfasts were replaced with bacon and eggs. “The people who run the place, they trust me because I worked as a cook before,” he said.

He wore an apron and a beanie and stood alone in the kitchen beneath the fluorescent lights, which gleamed against the foggy steel of the industrial-size appliances. The dishwasher would join him in an hour, but for now he had the place to himself as he began his three-times-a-day process of cooking meals for more than 100 other men struggling past addiction.

Once he made it through the six-month program, he would have a cooking job waiting for him, the program’s leaders told him. “But that’s only if my case works out,” he said. “The ‘but’ is the scary part.”

A program staffer drove him to the courthouse. From the highway, the sprawling white top of the Superdome dominated the skyline. Hanging from a building beside it, a large banner bearing the unibrowed face of New Orleans Pelicans star Anthony Davis promoted the NBA’s All-Star Weekend, which had kicked off in the city the night before. Further out of sight, toward the French Quarter, flags striped yellow, purple, and green flapped from temporary metal barricades along the streets. Mardi Gras was coming. A parade would snake through that city later that day. This was the New Orleans the world saw.

The courthouse doors did not open until 9 a.m., so the line stretched down the steep steps and onto the sidewalk. The mood was dour. This was the New Orleans William Varnado knew.

It is a place where change comes slow, many locals said. But city officials pointed to signs for optimism. In recent years, the mayor’s office and the City Council have called for a reversal of some of the policies that made New Orleans America’s incarceration capital. Last year, to punish Cannizzaro for his policies, the City Council passed a budget that cut the DA’s funding by 5%. “If he’s not listening, we have the power of the purse,” said Council Member Susan Guidry, chair of the body’s criminal justice committee.

As for the power of the people, it was muted when Cannizzaro was automatically re-elected in 2014 after a court ruled that his only challenger was not eligible to run for office. Some defense lawyers and city council members who spoke to BuzzFeed News were already speculating on who would challenge the incumbent in 2020.

In the wide, bright hallway of the courthouse’s second floor, footsteps clattered and people spoke in hushed voices. Varnado wore a black tie on a black and white checkered shirt, with black jeans and gray Vans. His hair, which he cut himself, was buzzed into a crisp fade. His beard was speckled with grays. He looked like a cool junior high math teacher — one who also happened to have gold fronts in his teeth and a small round tattoo under his left eye.

The courtroom door creaked when he pushed it open, and the inmates seated on a bench at the front, clad in orange jumpsuits, chains around their wrists and ankles and waists, turned their heads to see if it was somebody they knew. Duvander Hurst sat on the far left.

As other hearings took place, Hurst kept his eyes on the ground and Varnado, in the pews behind him, kept his eyes straight ahead. After half an hour of waiting, Hurst’s name was called and his and Varnado’s lawyer, Justin Harrell, took his place at a table beside his chained-up client.

The matter at hand was whether the judge should admit certain materials into evidence. At this hearing and others, prosecutors argued that Hurst had pressured Varnado to recant, through bribery or violent threat or both. Former detective Kaufman and former assistant district attorney Van Davis denied that they had coerced Varnado to identify Hurst. In her 2017 statement, Van Davis speculated that Varnado recanted because Hurst’s relatives found out he was living in Houston, and he was scared — just as he’d been scared into leaving New Orleans after the murder trial. Harrell argued that it was prosecutors who were trying to scare Varnado “in the hopes that he recants his recantation.”

Varnado watched with animated eyes. He grimaced when the prosecutor questioned his credibility. He nodded when Harrell remarked that Varnado had more credibility than the disgraced detective — Kaufman — who had taken his statement.

Within minutes, the hearing was done and the next court date — pretrial hearings for both Hurst and Varnado — was set for early April. Outside, Varnado let out a long, exasperated groan.

Behind him, a young man in Air Jordans and a shiny Oklahoma City Thunder jacket exited the front doors. As he descended the steps, he turned his head back toward the courthouse and shouted, “Fuck y’all!” Then, his eyes back on the steps, his voice under his breath in a bitter hiss, “Fuck y’all.”

Varnado, trying and failing to hold it in, laughed a big warm satisfying laugh. It was the kind of laugh that seemed to say: Amen, brother. ●

Outside Your Bubble is a BuzzFeed News effort to bring you a diversity of thought and opinion from around the internet. If you don’t see your viewpoint represented, contact the curator at bubble@buzzfeed.com. Click here for more on Outside Your Bubble.