John Pugh died at 9:34 p.m. on May 10, 2013. He was 68 years old, paralyzed from the waist down, and had diabetes, anemia, high blood pressure, chronic neck and back pains, pneumonia, a bladder infection, a bone infection, and severe bedsores. He was taking 18 different medications and spent his final days at the Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx. Over the previous year, his condition had worsened to the point that doctors deemed his accumulated ailments irreversible and shifted their focus to minimizing his pain. “Long-term prognosis is poor,” one doctor wrote six months before his death.

“He was real sick,” said Jacqueline McKenzie, who lived in Pugh’s apartment building. “And he just got sicker and sicker.”

Dr. Susan Ely, a deputy chief examiner at the Bronx Medical Examiner’s Office, performed the autopsy. In her notes, she reported that Pugh had died from sepsis caused by the infections in his lungs, bladder, hip bone, and the open wounds on his legs and back. He had gotten these infections, Ely concluded, because he was paralyzed, and he was paralyzed because of the bullet that struck him in the back nearly 29 years earlier.

Under “Cause of Death,” Ely wrote: “septic complications of paraplegia due to remote gunshot wound of torso with injury of spinal cord.”

In her official ruling on the “Manner of Death,” Ely wrote: “homicide (shot by another).”

The consequences of this ruling would ripple forward over the next three years, setting off questions of medicine and justice that would determine the future of a man's freedom, a fate that remained unresolved until this past September.

Carlos Carromero believed he had turned his life around. He had moved in with his cousins and aunties in Providence, Rhode Island, in 2011. He had met a girl he planned to marry. He had started going to church. He had kicked his heroin addiction. He had gotten a job at a jewelry factory — the first legal, tax-paying job he’d ever had. “It wasn’t a lot of money,” he said, “but I was proud I was finally living right.”

After clocking out of work on November 6, 2013, he headed to an auto shop to pick up parts for his girlfriend’s car. He was 44 years old but looked a decade older, aged by hard times, his face rugged and his hair graying. He saw the police officers and cars as soon as he stepped out of the auto shop at around 5:50 p.m. More than a dozen cops surrounded him. “I was confused,” he said. “I didn’t have a clue what was happening.”

At the Providence precinct, a New York City Police Department detective told Carromero that he was under arrest for the murder of John Pugh. “They told me it was for the 1984 shooting and I couldn't believe it,” he said. “I didn’t understand how they could do that.”

“I already did my time for what I did."

Carromero had been arrested for that shooting 29 years earlier, pleaded guilty to attempted murder, and served 10 years in prison before being released on parole in 1995.

“I felt bad that that man died, but how can they say that I caused his death all these years later?” Carromero said. “I already did my time for what I did.”

After the detective explained the situation, Carromero flipped the table and began shouting. Then his fury turned to despair, and he began sobbing. In the back of the police car, he cried for much of the ride to New York City.

Bronx County District Attorney Robert Johnson charged Carromero with second-degree murder, using a “delayed death” law that allows prosecutors to file murder charges even if a victim dies years after the original injury. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of such laws in 1912, ruling that they did not amount to double jeopardy because a murder charge filed after death was different from an attempted murder or assault charge filed while a victim was alive.

But the case against Carromero is one of the most extreme applications of this law. At the time of Carromero’s 2013 arrest, a defendant had never been convicted in a delayed death case that stretched as long as 29 years, said NYU criminal law professor James Jacobs, echoing the statements of more than a dozen law professors, criminal defense attorneys, and former prosecutors who spoke to BuzzFeed News. Even the judge overseeing the case, Steven Barrett, called Carromero’s situation “unusual.”

By pressing forward, the office brought forth a case that explored the very purpose of punishment in the court system and questioned what it means for justice to be served. To DA Johnson, here was a chance to lock up a “career criminal” who had caused lifelong suffering to an innocent man. To Kyle Watters, Carromero’s court-appointed defense attorney, here was “an absurdity that is so gross as to shock the general moral or common sense.”

And at the center of it all were two men, one too poor to afford better medical care as his health deteriorated and the other too poor to afford a stronger legal team to protect him from this exceptionally long arm of the law.

A hundred years ago, Carromero would not have faced this murder charge. Through the 18th and 19th centuries, a person was not criminally liable for homicide if the victim died more than one year and one day after the original crime. Rooted in English common law, the “year-and-a-day” rule was necessary because medicine was not advanced enough to trace a person’s cause of death after such a long stretch of time.

Scientific and technological advances changed that in the middle of the 20th century.

A hundred years ago, Carromero would not have faced this murder charge.

Over the years, 28 states, including New York, eliminated their “year-and-a-day” law. In 21 states, the rule remains on the books because it has not been challenged in court. Only one state, Alabama, actively upheld the law. California replaced it with a “three-years-and-a-day” law, but no other state has adopted a new time limit.

Delayed death cases are rare — experts estimate that there have been fewer than 100 over the last century. With people living longer, directly connecting a death to a long-ago attack, with years of variables and unknowns in between, is complicated. If the case makes it to trial, “it’s a difficult jury question that could involve complex medical testimony about other contributing causes,” said Stanford Law School professor Robert Weisberg.

Prosecutors in Philadelphia charged William Barnes with murder 41 years after he shot police officer Walter Barclay Jr., who died from a urinary tract infection in 2007. Barnes, who had served 20 years for the shooting, was acquitted of murder after defense attorneys showed that Barclay had suffered other injuries over the years in two car accidents and a fall from his wheelchair. The attorneys convinced jurors that any of those injuries — and not the gunshot — might have caused the fatal infection.

Prosecutors in Lake County, Illinois, considered charging Quincy Greenwood with murder 12 years after he hit Jorge Lopez in the head with the butt of an ax. Lopez was in a coma for the rest of his life before dying in 2000. The coroner ruled that the cause of death was complications from “blunt head trauma.” Prosecutors dropped the case because they believed they could not prove that this trauma stemmed from Greenwood’s attack.

When Ronald Reagan’s press secretary, James Brady, died in 2014 at age 73, from injuries caused by the bullets he took during the 1981 assassination attempt on the president, federal prosecutors thought about charging John Hinckley Jr. with murder. They decided against it because Hinckley had been found not guilty by reason of insanity in the original trial and because Washington D.C.'s year-and-a-day law was still on the books when Brady was shot.

Bronx DA Johnson was under no obligation to charge Carromero. But prosecutors argued that Carromero should face consequences not just for Pugh’s death but for his 29 years of struggle. “John never walked again,” an assistant district attorney wrote in a court filing. “He lost his job, he lost his girlfriend, his life was forever changed. A man who had once been independent became entirely dependent on others to accomplish the slightest task.”

Two days after the arrest, Carromero appeared in court for his first hearing. He pleaded not guilty and told his lawyer that he wanted to take the case to a jury. The judge denied him bail. Carromero would have to wait for his trial at Rikers Island.

John Pugh and his eight siblings grew up on a farm in rural Saluda, South Carolina. His mother died when he was young. While his father was at work at a textile factory, Pugh and his siblings tended the farm, picking corn and cotton and feeding the chickens. The children slept four to a bed in a modest house without a living room. “We didn’t have heat, so we kept each other warm,” said his older brother, Howard Pugh.

Pugh was stubborn and adventurous. As a teen, he raced cars in the backwoods and picked up a reputation as one of the area’s best drivers. He wasn’t as good at basketball and baseball, but he played anyway — “he always liked to do stuff that he couldn’t do,” Howard said. “He was headstrong like that.” When he graduated high school, his father wanted him to go to college nearby. Most of his classmates followed that path, sticking around town to run the family farm, maybe picking up a second job on the side. But John was restless and eager to escape. “He didn’t wanna farm no more,” said his sister-in-law, Viola Pugh. “So he moved up north. He always been independent, always did for himself.” He didn’t tell many people that he was heading to New York City. “Just kinda picked up and left,” Howard said. “Wasn’t no going-away party or nothing.”

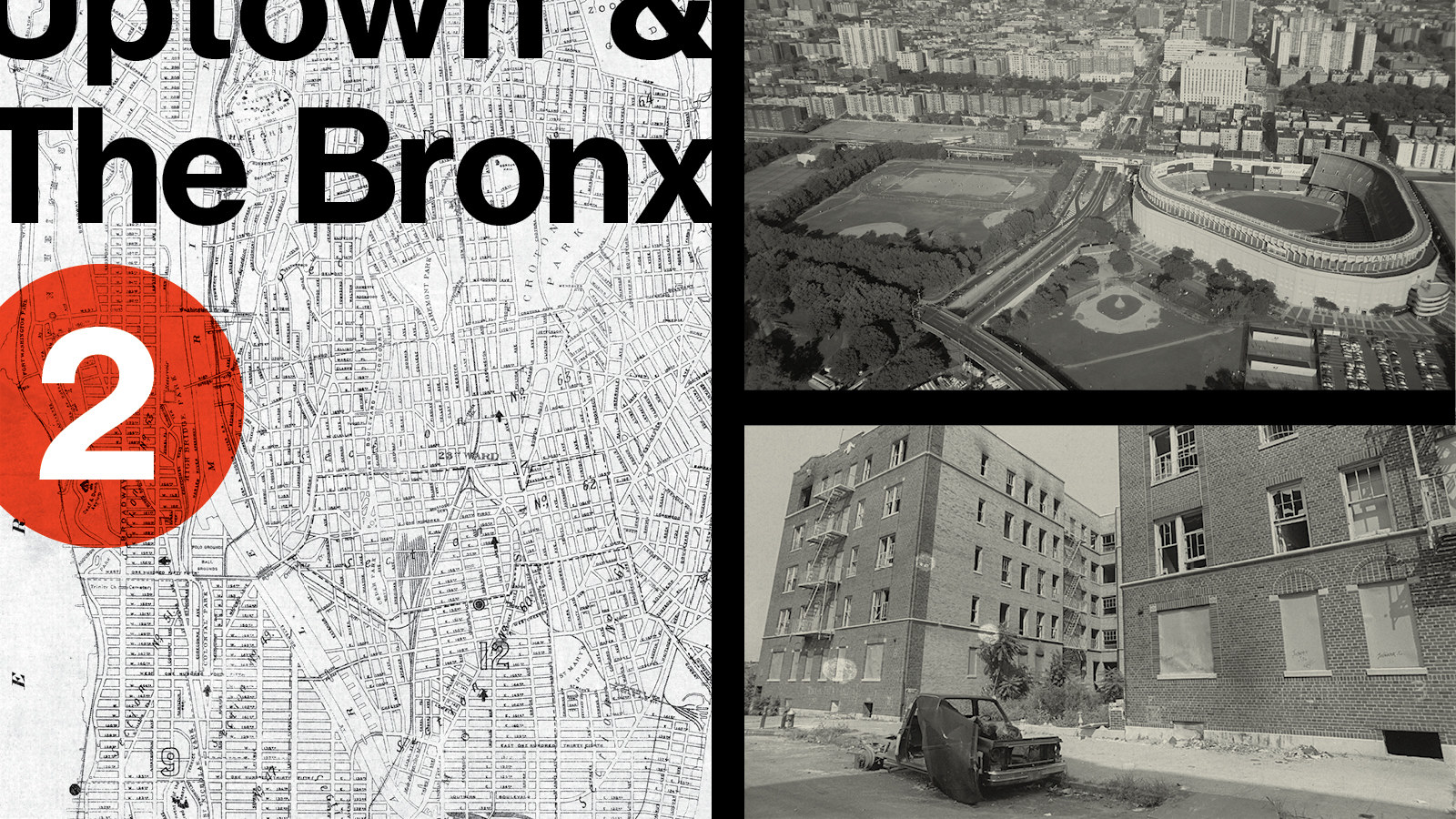

He settled into his new city quickly, finding an apartment in the Fordham Heights neighborhood of the Bronx and making money driving taxis and tractor-trailers. He made new friends, but visited his family in South Carolina at least once a year. When Howard came up to visit him, John proudly showed him around. “He loved it there,” Howard said. “He’d made his own happy life.”

On September 8, 1984, Pugh joined friends to watch a college football game at Yankee Stadium, according to witness statements to police. It was a pleasant evening, and after the game, Pugh and three others decided to walk to a friend’s place. When they reached 155th Street, two of Pugh’s friends, Joseph Findley and Oscar Ramey, stopped and turned to stare at an abandoned building. They had lived in the building when young and were disappointed to see its windows shattered or boarded up, casualties of the blight that had swept New York City.

A teenager standing in front of the building eyed the group. The boy wore an unbuttoned black shirt and cut-off jeans. The men in the group didn’t pay him any mind — until he spoke up, his voice loud and angry: “What the fuck you looking at?”

Carlos Carromero grew up in a small house on 154th Street in the Bronx. His mother lived in Puerto Rico and his father was gone from the start, so his grandmother raised him. He struggled in school, cut class often, and dropped out after eighth grade. A relative sexually abused him when he was 5, he said, and he did all he could to stay out of the house. He stole cars for joyrides and spent most of his time on the streets. He began working for a local drug crew when he was 12 years old, and by the time he was 16 he was selling crack and dope in front of the crew’s stash spot, an abandoned building on 155th Street.

One September evening in 1984, he watched a group of men walk slowly up the block, stop a few feet in front of him, and stare into the cracked windows of the stash spot.

“What the fuck you looking at?” he said to them.

Carromero told the men to move. One of them, John Pugh, stepped up to Carromero. They traded words. Pugh threw a punch. Watching from inside the building, Carromero’s partner, an older teen, ran onto the sidewalk and fired three shots into the air. Pugh and his friends retreated. Carromero went into the building and grabbed his own pistol. “I was scared,” he later told police. “I pointed a gun at him so he could walk away.”

And Pugh began to do just that, and as he left, he said to Carromero, “What are you gonna do, shoot me in the back?”

Carromero’s partner said, “Shoot him. He punched you in the face.”

Carromero would maintain that he did not intend to shoot Pugh, that he was only waiting for him to leave. “My hand was shaking,” he told police. “The gun went off.”

The bullet struck Pugh in the spine, near the T-10 vertebrae in the middle of his back.

He fired a single shot. The bullet struck Pugh in the spine, near the T10 vertebra in the middle of his back. Carromero dropped the gun and took off running. He raced to his grandmother’s house and hid under his bed, where he stayed until she and his uncle returned from church. He told his uncle what had happened and his uncle told him to leave town. The next day, he took a cab to JFK and hopped on the first flight to Puerto Rico. He stayed with his mother but did not enjoy his time there. “I missed the lifestyle of New York City,” he said, “the girls and money and excitement.” He returned after four months.

Back in the Bronx, Carromero lay low. For nearly eight months, he avoided police. But on September 3, 1985, officers finally spotted him. There had been a warrant out for his arrest ever since witnesses picked his photo from a lineup in the days after he shot Pugh. At the precinct, he offered two cops $25,000 to let him go. They added two counts of bribery on top of the attempted murder charge. Seven months later, he pleaded guilty. A judge sentenced him to 6 to 18 years in prison. He behaved well behind bars, got his GED, showed remorse, and made parole within a decade.

For a few years, Carromero lived a clean life, but like so many prisoners released into a world that shuns felons, he slipped back into bad habits: heroin, burglaries, and car thefts. He spent his days in a haze, on dirty mattresses in drug dens, wondering where the money for his next hit would come from. He picked up 10 misdemeanor convictions within 13 years — but none for violent crimes.

In 2011, 16 years after his release from prison, Carromero was shot in the ankle during a street fight. The brush with violence, he said, shocked him. He decided he needed to leave New York City for his life to improve.

He moved to Philadelphia with his girlfriend. There, he dug around on Facebook and tracked down a few cousins and aunties who lived in Rhode Island. He moved to Providence and began his new life. He took up boxing lessons and spent his free time playing video games on his cousin’s Wii. He cut himself off from heroin, pushing through the withdrawals. “I was going insane,” he said. “But enough was enough.” He tried to fight the symptoms with cold showers and long jogs. The cravings still lingered, but he stayed clean.

“I remember when he first moved here, I seen a lot of anger in him and a lot of pain in him,” said his cousin, Angel Romero. “He was real skinny, too. But then he came a long way. He became a different man.”

“He turned his life around,” said another cousin, Maria Romero, “and then they just locked him up.”

Carromero was not a danger to the public, his cousins said. How did it benefit society to throw him back behind bars?

To his cousins, Carromero had been rehabilitated. He was not a danger to the public, they said. How did it benefit society, they wondered, to throw him back behind bars?

The question strikes at the heart of the criminal justice system and its long philosophical struggle to balance punishment and rehabilitation. In response to the nationwide rise in crime rates from the 1960s to the early 1990s, legislators, prosecutors, and judges placed a greater emphasis on punishment. “Nobody wanted to be seen as soft on crime,” said Martin Horn, the executive director of the New York State Sentencing Commission. “And so people across the board called for and implemented stiffer penalties.”

As crime rates dropped to historic lows in recent years, and public safety was no longer a top concern for most Americans, legislators, prosecutors, and judges began reversing policies born out of the “tough on crime” era. The pendulum began to swing back toward rehabilitation: more funding for treatment for drug addicts; reduced sentences for nonviolent offenders who had behaved well in prison; elimination of life-without-parole sentences for juveniles.

But while prosecutors face little political risk in going easier on offenders convicted of drug or property crimes, the public is not as sympathetic to those with violent crimes on their records — a population that makes up half of all prison inmates. “Murder is different,” Horn said. “Where murder is concerned, there is a greater interest in retribution.”

The shift toward rehabilitation has been gradual and slight. New policies have not drilled into the core factors that cause mass incarceration but have simply been “snipping around the edges,” said Ashley Nellis, a senior research analyst at The Sentencing Project, a nonprofit that researches criminal justice policy. “Addressing the people convicted of more serious crimes is a high-stakes bargain for prosecutors. It doesn’t just come down to being about public safety — a lot of people who engage in crime age out of it. But politics plays a role in all this.” In recent months, political figures like President-elect Donald Trump and Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley have pointed to upticks in homicide rates in several big cities to falsely suggest that national crime rates are surging upward. In fact, 2015 had the third-lowest violent crime rate of the last 20 years.

The election of Trump, who proposed a national “stop-and-frisk” policy, suggested that a large swath of American voters are, at the very least, open to bringing back elements of the tough-on-crime era. But results of local races across the country also showed a growing national appetite to do just the opposite. In Arizona, Maricopa County residents voted out Sheriff Joe Arpaio, who had gained national attention for his hard-line stance against immigrants. In Tampa, Houston, and Denver, voters selected new district attorneys who had campaigned on promises to roll back the harsh practices of the past. In California, Oklahoma, and New Mexico, voters passed measures aimed at reducing incarceration rates.

“The country still doesn’t have consensus on what we want our criminal justice system to accomplish.”

“The country still doesn’t have consensus on what we want our criminal justice system to accomplish,” Horn said. “Do we want it to be rehabilitative or punitive? The main tool in our belt is imprisonment, and so we respond to all crimes the same way.”

It is the way the Bronx district attorney’s office responded when the medical examiner ruled on Pugh’s death. “If they rule it’s a homicide, we are bound to look into that,” said Patrice O'Shaughnessy, the office spokesperson under new Bronx DA Darcel Clark, who replaced Johnson in 2016. “The bullet wound led to his death. This poor guy, he just suffered.”

Four criminal justice experts who spoke with BuzzFeed News questioned whether this case was a proper use of resources. The answer, they agreed, came down to whether Carromero remained a threat to the public.

The Bronx DA’s office suggested that he was, noting that he “continued to be released from jails and penitentiaries only to commit additional crimes.” But in their arguments, prosecutors did not address Carromero’s claim that he had since straightened out his life.

Assistant District Attorney Adam Oustatcher argued in a motion that this “second prosecution” against Carromero was based upon “a fair reading of the law and the pursuit of a just resolution.” Legally, the DA’s office was charging Carromero for Pugh’s death, not for his 29 years of struggle. Carromero had already been convicted and sentenced for sending Pugh into a lifetime of paralysis. But the thrust of their argument centered on the pain he had caused Pugh, and the implication that the shooter had not been sufficiently punished for the suffering he had caused the victim.

“From the moment the defendant shot him until the moment he died, John was subject to a torturous existence,” Oustatcher wrote in a motion. “John was a healthy young man. He was an athlete, he was employed, he had a girlfriend, and he was a proud member of his community. The defendant decided to end that.”

Over the years, Carromero had occasionally wondered about Pugh. What had become of his life since that evening in 1984? “I always just hoped he was doing okay,” he said. But the thoughts were fleeting and far between. Carromero, after all, had his own problems. “Then after I got locked up and I found out he was dead, it was coming to my mind every day,” he said. One night on Rikers Island, he saw John Pugh in a dream. The man’s face, looking just as it did in 1984, stared at him and his voice, calm and steady, said, “I got you. I got you back.”

John Pugh was bitter. His brother Howard saw it on his face — when he got dressed in the morning, when he wheeled his chair onto a subway station elevator, when he painstakingly leaned over and reached for something on the ground, his face betraying the relentless frustration he faced in his new life. "When he dropped things, it always kinda got to me," Howard said.

He was bitter but never admitted to it. He leaned on his warm, outgoing temperament to put people at ease with his paralysis. “He was always uplifting and encouraging,” his sister-in-law Viola said. “He didn’t just give in to his injury. He fought in his daily life. He went everywhere and did everything. He never felt sorry for himself.” Still stubborn, he committed to living an independent and fulfilling life. He played in a wheelchair basketball league. He completed the New York City marathon. He drank beers with friends and manned the grill at cookouts. He took classes at a community college. He lived on his own, in an apartment building for the elderly and those with disabilities. Though he could no longer work as a cabbie, his Social Security checks and Section 8 housing vouchers covered his rent and living expenses.

He became a popular figure in his building. He let his neighbors use his computer, sometimes teaching them how. Residents recalled him rolling down their hallways, greeting them, updating them on his latest endeavors. He met with advocates to help them lobby for more rights and services for people with disabilities. He organized voter registration drives. He led a campaign to persuade Board of Elections officials to designate the building as a polling place. “He was a strong personality with strong convictions and he stood up for what he believed in,” said Ruben Mojica, a security guard at the building. “A lot of people remember him for that.”

He lived proudly and purposefully for many years after the shooting. But his body deteriorated faster than his spirit. He grew overweight and developed diabetes, hypertension, and anemia. He lost four toes to gangrene. By 2007, his body had become wracked by pressure ulcers, better known as bedsores, which grew worse as Pugh aged, his declining energy and damaged body keeping him on his back for days at a time. He began making regular trips to the hospital.

Neighbors urged him to move into a nursing home, where he could receive round-the-clock care, but Pugh resisted. Once he moved into a nursing home, he believed, he would lose the independence he’d worked so hard to attain. As Pugh grew more ill, his neighbors stopped seeing him around the hallways. “He wasn’t like he used to be,” said his neighbor Jacqueline McKenzie. “He just couldn’t do it anymore.”

In 2009, he finally relented, checking into a nursing home temporarily, at least until he recovered enough to take care of himself. The first time, he left within days. Over the next three years, he tried two more nursing homes but never stayed more than several months. “He was always hostile to them,” Viola said. Back home on his own, his condition continued to worsen, and during those final few years he was admitted into his local hospital, the Montefiore Medical Center, 16 times.

When Pugh met with doctors, he told them that his goal was to return home and live independently. According to hospital records, he complained to one doctor that “he wasn’t getting appropriate care from the nurses” at a nursing home, and he claimed that he’d be better off at his apartment, with a nursing aide dropping by to dress his wounds and check on his well-being. He didn’t have the money for such private care, however, and insurance didn’t cover it, he told his relatives.

“His spirit is incredible,” Dr. Ellen Harrison wrote in her notes. “[Pugh] wants to go home. Wants to go back to playing wheelchair basketball. I wish both of his wishes were realistic [but I’m] not confident they are.”

He lived proudly and purposefully for many years after the shooting. But his body deteriorated faster than his spirit.

By 2012, his bedsores had become “dramatic,” according to hospital records, stretching from his lower buttocks to the middle of his back, 2 centimeters deep in some places, “with extensions to the bone.” The wounds had led to a bone infection and “recurrent sepsis,” which damaged his organs and often left Pugh fatigued, feverish, dizzy, and confused. In October 2012, Harrison wrote in her notes, “He is hoping for a life other than lying in bed or in a chair unremittingly. Many barriers to finding a solution for him.” Another doctor noted: “It seems like discharge to home is nearly impossible at the current state.”

As his fate became clear, Pugh’s optimism began to falter. During a psychiatric consultation, Pugh said he was “tired of being sick all the time” and “reported wanting to die,” according to hospital records. A doctor diagnosed him with depression. During a trip to the hospital, he became “very distressed” and “briefly tearful.”

“Patient is beginning to realize the gravity of his situation,” a doctor wrote in November 2012.

In April 2013, Pugh checked into the hospital after a day of nonstop vomiting. Doctors diagnosed him with sepsis, a bladder infection, and pneumonia. His weakened body did not recover. On May 4, doctors transferred him to the emergency room. His heart stopped the next day, and he was dead five days later.

Pugh’s relatives did not clamor for Carromero’s arrest. Several said they only learned about the murder charge from reporters who called them asking for comment. His niece, who requested anonymity, told the New York Daily News in 2013, “If he’s done his time, to rearrest somebody again, I don’t really understand it.” His brother Howard recently told BuzzFeed News, “The damage is already done now. I don’t know if they should’ve went after the guy.”

Carromero’s defense attorneys tried to get the case dismissed. They claimed that the charges constituted double jeopardy; that the lawyer from the original case was incompetent for not warning his defendant that he might face murder charges down the line if Pugh died; that the delayed death law was not intended to be applied after such a long stretch of time. But a judge rejected the motions and the case moved forward.

From his cell on Rikers Island, Carromero refused a plea deal. His court-appointed defense attorney, Sam Braverman, who had taken over the case from Watters, planned to argue that too much time had passed and too many factors had emerged to hold Carromero legally responsible for Pugh’s death. Pugh, after all, was an old man who had lived past the age of retirement. He had developed crippling bedsores in a state with the third highest rate of pressure ulcers among nursing home residents, according to data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. “The reason he died is acute medical malpractice,” Braverman said. “He was in terrible shape, with nobody caring for him.”

Pugh’s relatives did not clamor for Carromero’s arrest.

But Braverman, who defends people who cannot afford private attorneys, was working dozens of cases at a time and lacked the resources for a fast and thorough investigation on Carromero’s behalf. Making matters even slower, the Bronx County Hall of Justice was struggling through a historic backlog of cases, leading to delays longer than almost anywhere else in the country. In a speech in 2013, Jonathan Lippman, the highest-ranking judge in New York state at the time, called the borough’s delays “intolerable” and “entirely unacceptable.”

And so in the spring of 2016, nearly three years after his arrest, Carromero remained in jail, still without a trial date. He’d heard of some Bronx defendants awaiting trial five, six, seven years. He believed it was unfair that he was being punished, and he yearned for a jury to vindicate his sense of injustice before the judge and prosecutors. But more than anything else, he wanted to return to the life he had left in Rhode Island.

His lawyer told him that he could still take the plea deal: 15 years for manslaughter. With the time he had served awaiting trial added to the time he had served for the original crime, Carromero would be free by the end of the year — much sooner than if he continued on to trial.

He took the deal. He was transferred to a prison upstate in Newburgh and was released in late September. “But I should have been home the whole time,” Carromero said. “Three years wasted. It’s been like a nightmare.” He stood outside the prison on that bright afternoon, unsure what to do. “I was happy,” he said. “I was confused. I was anxious. It felt like another new beginning.”

He’d had a new beginning when he left prison in 1995. He’d had a new beginning when he got clean in 2011. Each time, his new life had sputtered and he’d fallen back into circumstances he’d hoped to escape. “This time is not like before,” he said to himself. He boarded a bus. He arrived in Providence four hours later. His family was gathered at the house to welcome him. ●