LONDON — Politics and balconies don’t go well together in Italy. Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini gave many of his speeches from a small balcony overlooking Piazza Venezia, a square in central Rome. It was from there in June 1940 that he declared war on France and the United Kingdom.

Ever since, Italian prime ministers have tended to avoid standing on the balconies of Rome’s buildings of power. World Cup victory celebrations have been brief exceptions in the nation’s postwar history.

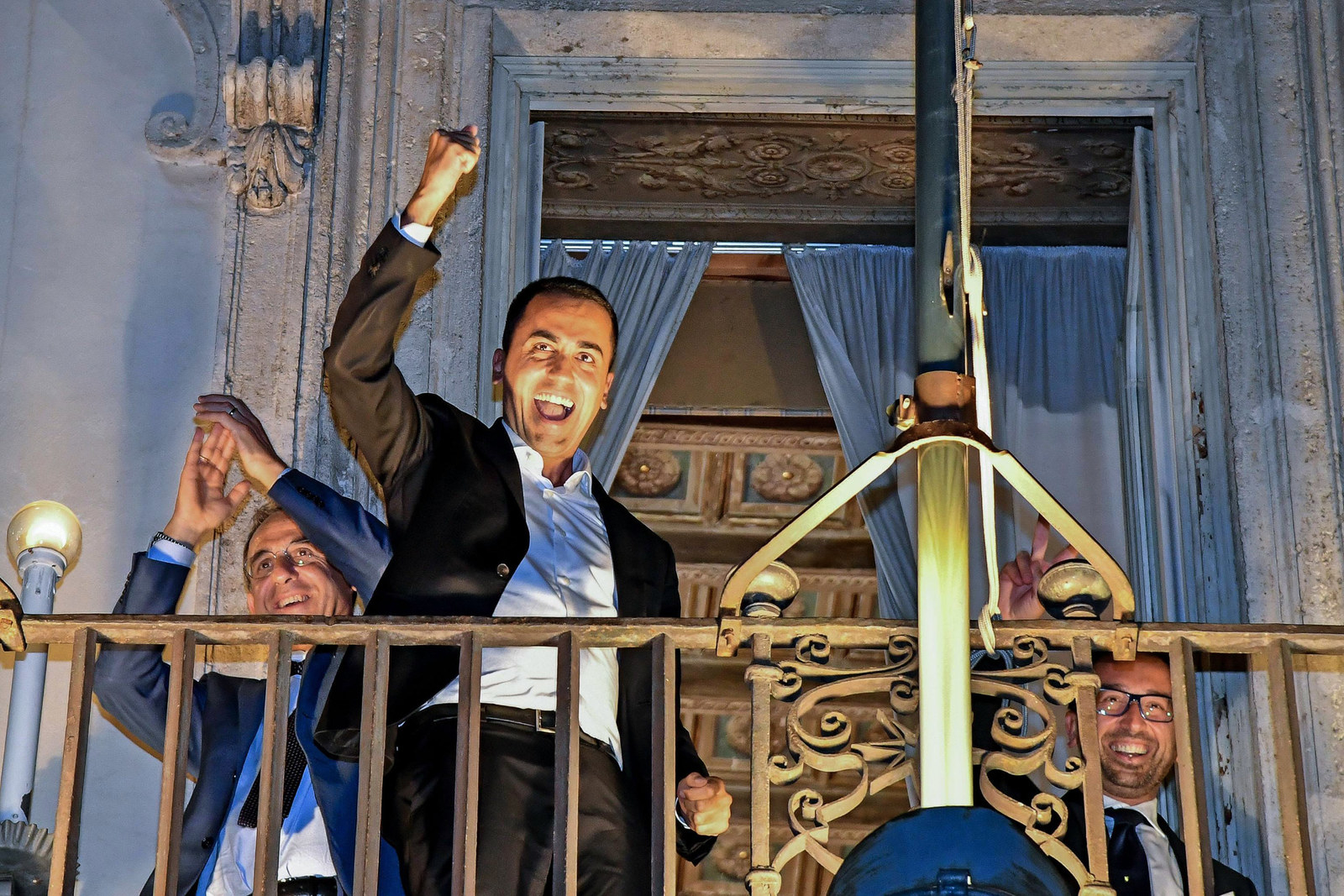

But the custom was clumsily ignored last week when Deputy Prime Minister Luigi Di Maio looked down from the building that houses the Italian prime minister’s office, his fist punching the air. He was pictured there alongside a group of ministers of his Five Star Movement, the populist party that since June has governed in coalition with the nationalist League, all of them extending V-for-victory signs to a small crowd of flag-waving party members and MPs assembled below.

They were jubilant because they’d reached a Cabinet-wide agreement on Italy’s next budget after weeks of vicious arguments between the Five Star Movement and finance ministry officials, who believe the proposed deficit target is unsustainable.

“We have abolished poverty,” Di Maio, 32, beamed. In a blog post published two days later, he went on to call all those who opposed the plans “enemies of Italy.”

The spending proposals, which would see Italy’s deficit balloon beyond levels considered permissible by European Union rules, are fully backed by League leader Matteo Salvini, Italy’s other deputy prime minister. “I don’t give a damn about Brussels,” Salvini, who is also interior minister, said over the weekend. On Monday he upped the tempo further, accusing European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker of damaging Italy’s economy, and threatened to take legal action.

The budget incident isn’t isolated. It sits within a crescendo of verbal attacks carried out by both the Five Star Movement and the League against officials, institutions, the media, and anything and anyone perceived to stand in their way.

And the attacks appear to be working — in the court of public opinion, Salvini and Di Maio are winning. Their two parties are polling at a combined 60%. Nearly 1 in 3 voters now support Salvini’s League — known in Italy as Lega — as its popularity has expanded well beyond its traditional northern power base. Opposition parties on both the center-right and center-left, meanwhile, are languishing at record lows.

Echoing Donald Trump’s lessons in the US, Salvini and Di Maio favor social media as their weapon of choice. It played a crucial role in the two parties’ climb to power and is central to how they now manage the business of government.

And the Trump playbook could cause lasting damage in a country where checks and balances, civil society, and the media are weaker and less adept at holding the powerful to account than in the US.

Strings of tweets and Facebook posts are becoming full-blown policies — and the events of recent weeks have raised alarms that many preelection fears are coming true as the two parties of government seem intent on chipping away at the nation’s institutions and deteriorating its social fabric, putting Italy’s finances and its place in Europe up for question.

Some officials, who have seen multiple Italian governments come and go, believe the Five Star Movement’s ferocity is driven by incompetence more than grand design. “Attacks on officials and civil servants is the return of a classic theme. Now it’s opportunism by an inadequately prepared leadership class that doesn’t accept the world is more complicated than how they’ve explained it to voters,” a government insider, who talked to BuzzFeed News on condition of anonymity, said.

The lead-up to last week’s Cabinet meeting on the budget was incendiary. In a leaked audio clip published by Italian media, Rocco Casalino, the spokesperson of Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte, is heard telling journalists that civil servants working at the Finance Ministry are “pieces of shit” trying to obstruct the Five Star Movement’s welfare plans. Casalino regularly spins for Di Maio and the Five Star Movement. He is a former Big Brother contestant.

If they don’t back the plans, the Five Star Movement will dedicate all of 2019 to seeking revenge, and take them out, Casalino said of the officials. “Knives will be out,” he says in the clip.

Di Maio, who has said he doesn’t trust data produced by government officials and has their numbers double checked, backed Casalino.

Rowdy political leaders aren’t a newly introduced feature of Italian political life. Former prime ministers Silvio Berlusconi and Matteo Renzi had their bust-ups with civil and public servants too.

But this wave of attacks feels different, and has made officials uneasy. “What this lot doesn’t understand is that if someone says ‘This can’t be done for legal or economic reasons, or because it’s not in the longer-term interests of the country,’ it’s not because they support the opposition party,” a second official, who also asked not to be named, said.

“It’s the extremely dangerous Five Star Movement mentality: Their MPs are all forced to toe the party line, and now they want to subdue the civil service and public sector in the same way,” the official added.

Prime Minister Conte is perceived by many as a weak figurehead. The real power lies with Salvini and Di Maio, who are seen as Italy’s de facto leaders.

The two deputy prime ministers’ social media activity is about grabbing attention, setting the news agenda, and castigating opponents. A serving official, who also asked for anonymity, explained how the two men and their teams are constantly engaged in a real-time online battle to outdo each other and capture the day’s headlines.

But there are also signs that words are seeping into actions, which, if left unchecked, could steadily erode the country’s democratic and cultural institutions.

“In a democracy, no one person is above the law. We know this since Socrates,” another source close to government circles said.

“Recent coarse attacks are the manifestation of an intolerance towards the rule of law, and an inability to produce change within the patient timeframe demanded of a democracy,” the source, who asked not to be named, added. “Other forms of government are far quicker, but they’re called dictatorships.”

The most eye-catching move by the League and Five Star Movement in the four months since taking office has been the appointment of journalist Marcello Foa as chair of Italy’s state broadcaster RAI. Foa’s résumé includes spreading conspiracy theories about Hillary Clinton and satanic dinners, as well as false claims about vaccines.

Last year, he authored a news story stating the US military was preparing to mobilize 150,000 reservists for a possible war against Syria, Iran, North Korea, or Russia. No such mobilization ever happened. He has also written extensively against gay rights and questioned the Kremlin’s involvement in the poisoning of Russian double agent Sergei Skripal in Salisbury in the UK. “It’s too obvious for me,” he said of the evidence in the Skripal case during an interview published in the New York Times last week. “It’s a way of saying, ‘Oh, you see, Putin is the bad guy doing the bad thing,’” he added.

The appointment, which required support to extend beyond the League and Five Star Movement, was initially blocked by Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia party. But after private meetings between Berlusconi and Salvini, Forza Italia removed its veto.

So now, Foa, who once claimed that injecting too many vaccines causes shocks in children, and measles isn’t so terrifying, holds one of the most influential media positions in the country.

Foa, 55, is a former foreign editor at the Berlusconi family–owned Il Giornale newspaper, and more recently was the director of a publishing group in Lugano, Switzerland. In June 2017, its main title, the Italian-language Swiss newspaper Corriere del Ticino, published a front-page story claiming — falsely — that the German government was ordering the country’s police to play down Islamist terror threats. The story was later retracted because the documents it was based on weren’t authentic.

Abroad, Salvini has sided with Poland and Hungary in their ongoing disputes with the EU. Both governments are accused of undermining the rule of law, judicial independence, and press freedoms.

Salvini and Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán have framed next year’s European Parliament elections as a contest between their worldview — what Orbán calls a Christian “illiberal democracy” — and ideas embodied by French President Emmanuel Macron.

For both Salvini and Orbán, claims of sovereignty and anti-migrant rhetoric are the centerpiece of their respective platforms.

“He [Macron] leads the European force that backs migration, he’s the leader of those parties who back migration to Europe, and on the other side there’s us who want to stop illegal migration,” Orbán said at a joint press conference in August.

Salvini has pledged to bring together nationalist parties across Europe in an alliance of anti-immigration parties he calls a “league of Leagues.” He has formed a close relationship with the leaders of far-right and nationalist parties and movements in France, Sweden, Austria, the Netherlands, and Germany, among others. Taken together, this group of parties, some of which — including the League — have historically advocated leaving the eurozone and the EU, would be a formidable force in the next European Parliament.

Meanwhile, the Five Star Movement has yet to clearly set out its stall for next year’s EU vote. The party, which sits with UKIP — previously led by Nigel Farage — in the European Parliament, has flirted on and off with dropping the euro.

The Five Star Movement has built much of its success on the back of such ambivalent positions. It acted as a clearinghouse for a disparate array of protest groups and voices angry with everything, from vaccines to investing in major infrastructure projects.

The party’s rise to power has been punctuated by relentless attacks on the media and political opponents through the blog of party cofounder and former comedian Beppe Grillo, as well as via websites and Facebook pages linked to a private company owned by the movement’s other cofounder, the late entrepreneur Gianroberto Casaleggio. The pages and websites often pushed conspiracy theories and misinformation.

In office, the party’s hostility toward critical coverage has remained unaltered. In one example, Casalino threatened the newspaper Il Foglio, asking one of its journalists in July, “Now that Il Foglio will close, what will you do?” (The paper remains in operation.)

Salvini has nearly 900,000 followers on Twitter, 3.2 million people like his Facebook page, and another 740,000 accounts follow him on Instagram. Every day the League leader publishes a flurry of posts on the three platforms. Within a stream mostly consisting of anti-migrant rhetoric, news stories about crimes committed by immigrants, and his “Italians first” mantra, as well as chummy posts and photos of food, Salvini has turned his fire on judges, NGOs, foreign and domestic politicians, black footballers, the Roma community, the EU, and critical journalists, among others.

Like Trump’s in the US, Salvini’s tweets and posts dominate media coverage, while at the same time polarizing voters into two camps: those viscerally for Salvini and those ardently against him.

“Social media for Salvini, Facebook especially, which he focuses on most, is first of all the mechanism through which he maintains and activates his community,” Lorenzo Pregliasco, the cofounder of political analysis and polling firm Quorum/YouTrend, told BuzzFeed News.

“In the context of Italy, his community is significant in terms of numbers, activism, and conviction. This is clear, for example, when he posts live videos on Facebook. I think this direct dialogue with his base is the main distinctive trait of Salvini’s use of social media,” said Pregliasco, who has written extensively about the League leader’s use of social media.

“In fact, the narrative of Salvini as hero, ‘the captain’ and so on, is grounded in all this,” he added. (Salvini often addresses his community of followers as “amici,” which means friends in Italian. His supporters call him “Il Capitano,” the captain.)

Elsewhere, the Five Star Movement and the League have been blamed for forcing the head of the authority responsible for regulating the Italian securities market to resign last month.

The two parties then trained their sights on David Ermini, the recently elected vice president of the High Council of the Judiciary, an institution whose function it is to ensure the autonomy of the judiciary.

Two-thirds of the council is elected by the judiciary, while the rest are law professors and lawyers with at least 15 years of experience, and are elected by parliament.

Ermini is a former MP with the opposition center-left Democratic Party. The Five Star Movement, however, is among the parties that voted to elect him to the council back in July, making him eligible for the role of vice president. Nevertheless, in a Facebook post published last week, Di Maio described the choice of vice president as incredible. “The system is alive, and it fights against us,” he wrote.

The leader of the Five Star Movement has also threatened to remove from their posts officials and diplomats who support the EU’s trade deal with Canada, which the government has vowed to oppose.

Salvini too has used social media to lash out at the judiciary and, more broadly, to comment on decisions he disagrees with or endorses.

Last month, he opened a letter live on Facebook sent to him by a court in Palermo that was investigating his decision to stop migrants disembarking from a ship moored in the Sicilian port city.

As deputy prime minister he has criticized Italy’s rail company after a staff member faced the sack for insulting a group of Roma over the train’s PA system, and cheered the arrest of a small-town mayor accused of aiding immigrants who were in the country illegally.

Salvini’s outspokenness has followed him in a seamless transition from party leader to deputy prime minister that hasn’t seen his behavior change despite the institutional role he now occupies. Last summer, he posted about his support for the owner of a bathhouse under investigation for “apology of fascism,” which is a crime in Italy.

“Ideas should not be tried,” Salvini wrote on Facebook, offering to help with the entrepreneur’s legal defense.