Muddling through isn’t a bug in Italian politics, it’s the defining feature. The country is used to instability: It has had more than 60 governments since the end of the Second World War. And on the same day that Angela Merkel all but secured a fourth term, Italians were casting ballots hoping to figure out who would be the country’s seventh prime minister since she took office in Germany in 2005.

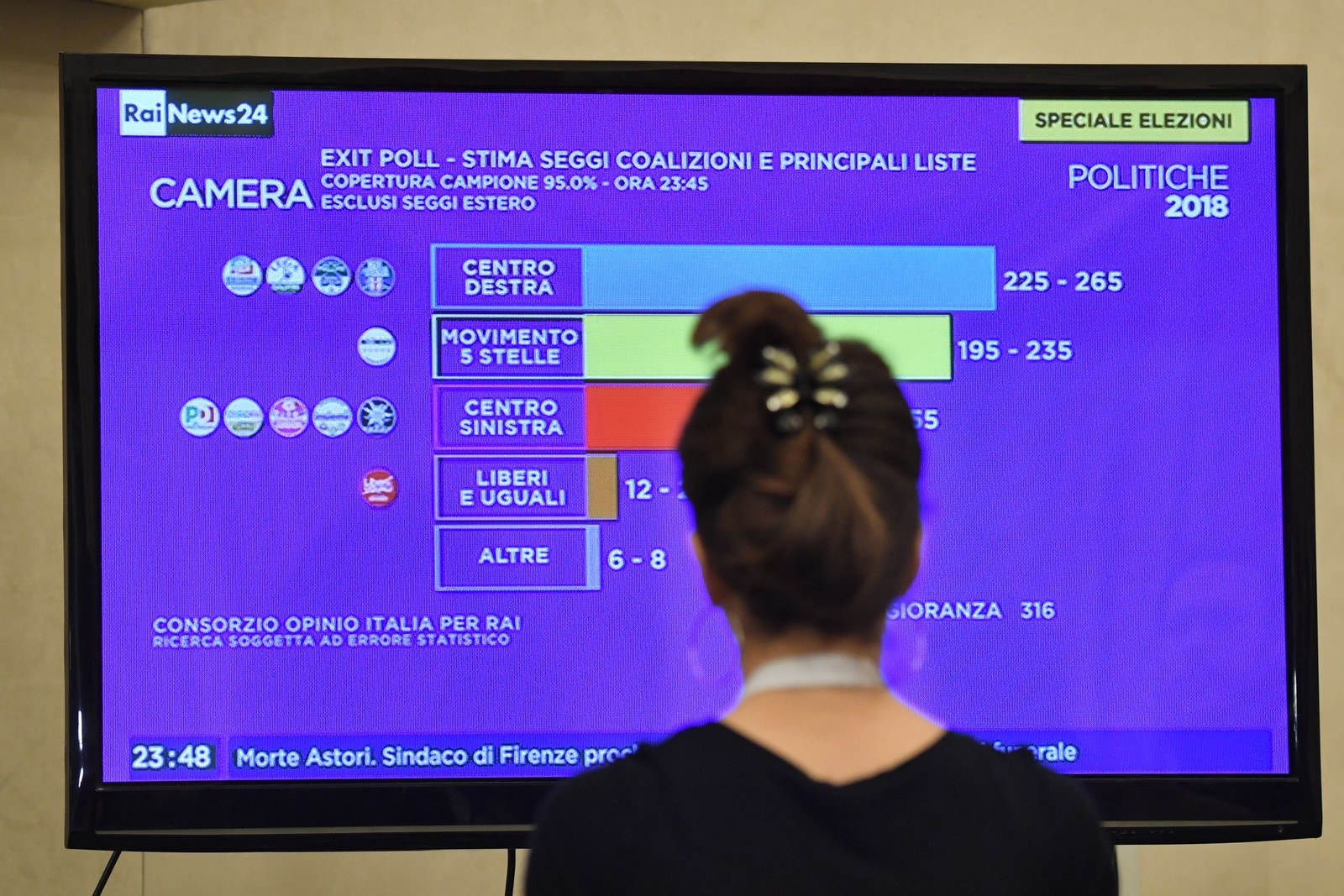

Now, with most votes counted, Italy is heading for another hung parliament. No single coalition or party is on track to win enough seats to govern alone.

This election, however, feels very different, because a mix of anti-establishment, populist, and far-right forces hold a parliamentary majority. Even if they don’t team up to form a coherent government, between them they hold the balance of power in what is the world’s eighth-largest economy, and the eurozone’s third biggest.

The Five Star Movement (M5S), a populist party like no other in Europe, cofounded by the comedian Beppe Grillo and a tech entrepreneur less than a decade ago, is by far the largest party in the country. According to projections, it is on course to win 32.5% of the vote, which translates into around 230 seats in Italy’s 650-seat parliament. The party swept the south of the country, in some regions winning close to 50% of the vote.

The centre-right is the largest coalition, with 37% of the vote and about 260 seats. But the largest player in the bloc isn’t the familiar 81-year-old Silvio Berlusconi and his Forza Italia party, who have led — and glued together — the coalition since its inception; it’s the Lega. Under the leadership of Matteo Salvini, the Lega has become a national force by reinventing itself as a far-right anti-immigrant party whose campaign slogan was “Italians first.”

About half of the electorate voted for the M5S or the Lega, the two parties that best tapped into voters’ anger and angst. Although they abandoned their anti-euro stances ahead of the election, both parties have in recent times backed exiting the single currency in some shape or form. They have also both flirted with the rhetoric of conspiracy theories, and picked up among their ranks anti-migrant trolls, anti-vaxxers, and fringe economists.

Meanwhile, the centre-left Democratic party of former prime minister Matteo Renzi is shy of 20% of the vote — its worst ever result, and confirmation of a trend that has characterised the past 25 years of Italian politics: Incumbent parties don’t win elections.

So what happens now? The next Italian government will be the product of arithmetic, political opportunism, and process.

A first big question is who will Italy’s president, Sergio Mattarella, first ask to have a go at forming a government: the M5S as the largest party or the centre-right as the largest coalition? Both the M5S and Lega claim to want the responsibility.

But the answer isn’t straightforward. A new parliament doesn’t sit before March 23. Its first task will be electing new speakers, which will provide an early indication of where alliances might be formed. The president will then formally consult with all parties to measure the pulse of possible scenarios before making a decision. Until then, there will be weeks of haggling behind the scenes.

If the mandate goes to the centre-right, Salvini, under the internal rules of the coalition, would be the bloc’s likely candidate for prime minister. If it goes to the M5S, the task would fall to the 31-year-old, mostly untested Luigi Di Maio.

The second question is whether Salvini will opt to back the M5S or whether he will instead take control of the centre-right. His dilemma is between power now, or the possibility of even greater power down the road. Salvini has an unprecedented opportunity: to forge the centre-right’s platform and identity post-Berlusconi. Forza Italia and Lega also govern together in numerous cities and regions, and any divorce now would be messy.

In a press conference on Monday morning, Salvini repeated several times that his responsibility was to create a government with a centre-right coalition, and he believed they could form one. He underlined that Lega was the largest party in the bloc, but added that any decision on who would get the call to form a government was the president’s. The Lega leader said he would talk to all parties, but excluded the possibility of broad and “odd” coalitions. And although he did not explicitly rule out an alliance with M5S, he criticised Di Maio’s flip-flopping on key issues, such as immigration, and stressed that he wasn't the kind of person who switches teams.

Despite dismissing the idea of a referendum on the euro, Salvini said the single currency was destined to fail. He said the EU had to change, and he lauded Hungary’s Viktor Orbán.

Salvini speaks: 1) sticking with centre-right, underlining Lega largest party in bloc, thinks they can form a gov't 2) but doesn't fully shut the door on other possible alliances 3) on EU: criticises euro, says wants to change the rules, lauds Orban

Still, ultimately, governing will depend on the numbers. Although the respective voter bases of the M5S and Lega look different, and M5S voters in the south may find a deal with a formerly secessionist party hard to stomach, the two have voted together more often than not in the last parliament. On numerous points — from minimum wages and reversing recent pension reforms to sticking two fingers up to the EU’s fiscal rules — agreement on a slim program isn’t inconceivable. The M5S is open to talks with all parties, Di Maio said on Monday.

A third question regards the Democratic party, and how it positions itself: Will the party go into opposition, or will it keep the door open to a possible agreement with the M5S or a Salvini-led centre-right coalition? A definitive answer is likely to come only once the party sorts out who will lead it after yesterday’s calamity.

The arithmetic, however, is clear: No government is possible without the support of either Lega or the M5S.

Should talks between the parties prove inconclusive, the president could attempt to nominate a technocratic or cross-party government. But its chances of survival are remote: Any such option would also require the support of a parliamentary majority.

If everything else fails, Mattarella could eventually be left with no choice but to call a new election.

All this takes place against the backdrop of a fragile economic recovery that fueled much of the rage that defined Sunday’s result. Whatever happens next, that anger is not going away anytime soon.

Italians, like the rest of Europe, can do little but wait in the meantime.