I spent the night before my 24th birthday beating The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time.

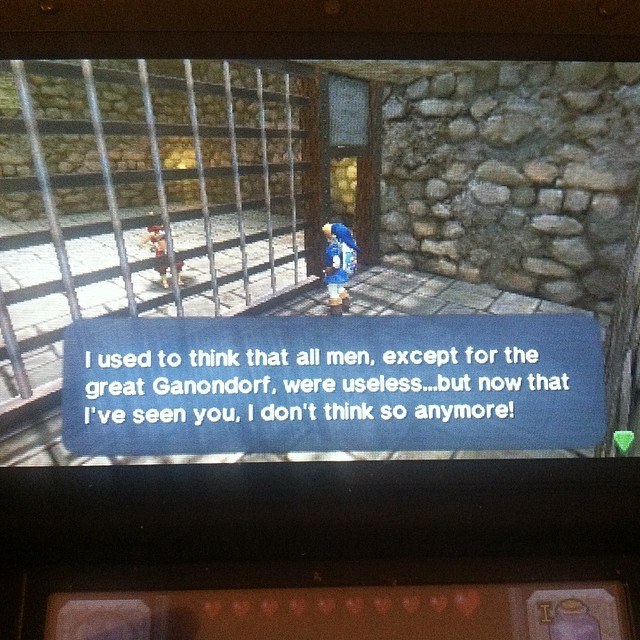

It was a rainy Monday. I seared a steak and drank a beer at my apartment before sitting on my bed to face off against Ganondorf, the villain whose machinations yank you through time, space, and a multitude of quasi-sexual interactions with quasi-human women over the 20-plus-hour course of the game. I drank a second beer.

I knew what to expect, vaguely. I'd played the game as a kid, nestled into the family couch with my younger brother and sister during late nights and early mornings. We'd take turns with the N64 controller or fight over it, and I'd watch after school as my next-door neighbor doggedly beat each temple in front of his own television, offering to do the same for me whenever I was stuck. I never took him up on the offer. Ocarina was too intricate and too challenging for us at the ages of 11, 7, and 4. I'd revisit it over the years and I watched as my brother completed it, but I never mustered up the time or the gumption to sit down and beat the whole thing on my own. It lived firmly in the past, one of those games that I always started and never finished.

But I got a red Nintendo 3DS XL for Christmas last year, and with it, the remastered Ocarina of Time. I'd asked for the game more out of curiosity and nostalgia than a genuine sense of desire to play. I remembered loving the sprawling yet nuanced game map but wasn't at all sure I'd have the patience to wend my way through it, especially when there were real things like jobs and boyfriends and happy hours to deal with. I wanted something new to do on the subway, though, something with more of a sense of — what? Urgency, maybe? — than my usual knitting or reading books that belonged to my roommate, so one morning in March I took the half-finished sock out of my bag and replaced it with my 3DS.

It started slowly. I was distracted those first few days of playing, and frustrated by how whenever I saved and shut the game, it would transport me back to a set location (even in its new form on the DS, Ocarina does not reward stop-and-start play). At the start, Link, the game's peculiar and wonderful main character, is a little kid, and so can't yet do most of the things I was impatient to do (Shoot arrows! Ride horses!). I'd completed this first part of the game many times the previous decade and was downright alarmed by how boring I found it this time around; what if everything I'd thought was so majestic and moving as a child was actually flat in the harsh light of now? What if it was me that had changed? I missed having my siblings' chattering voices in my ear, telling me that of course you have to get that weapon to enter the Water Temple, Alanna, why can't you get Biggoron's sword faster? One morning, I brought along the sock instead.

A week or so in, I finally wised up and plugged in my headphones. I'd been playing silently, too lazy to dig through my bag for my tangled earbuds before I'd had any coffee. It turns out that this was an insanely stupid thing to do. The heart of Ocarina is its music, from the songs you learn in order to change the flow of time and space to the haunting, swoopy, hollow notes that are the backdrop to everything you do. The music gives you a minor heart attack when an enemy appears and instantly comforts you when you enter a private home or shop. Without it, I was just going through the game's motions; with it, I was so immersed that I once rode the train two stops past my office and had to speed-walk all the way back.

The game provided texture to my life to a degree that's almost embarrassing. I liked feeling as though I was doing something on the subway, that I was somehow engaging with something that reached beyond the edges of myself. I got a small thrill whenever I noticed teen boys craning their necks to see what I was doing; a little kid tugged indignantly on his mother's sleeve one morning, stage-whispering, "If she gets to play, why can't I?"

Because I am an adult, I thought smugly, stabbing another carnivorous plant in the stem.

I liked the recognizable structure of the game, at its heart a classic quest to restore balance, and I liked that I had the freedom to move through this new world even as I was navigating my own. When I would complete an especially hard temple or arduous side quest, I'd brag about it to anyone I knew within earshot.

"Cool," my boyfriend or a co-worker would say. Sometimes: "Cool!" Once: "Could you turn that off? The light is annoying."

I heard myself being boring, but really I was just so excited, even relieved, to have this small, set series of tasks to complete every day. Fighting as Link helped to quiet the everyday din of voices in my own head, the shouldn't-have-said-thats or the wish-I-would'ves or the what-if-oh-no-what-ifs. I had just started seeing a therapist when I began playing, fed up with letting the vague but pervasive collection of anxieties I lug around creep too far into my everyday life.

Ocarina felt, in some small way, like a means of putting what I was starting to learn into (very controlled and low-stakes) practice: to own whatever was in front of me and stop being so goddamn paralyzed by the fear of failure. I didn't feel so much that I was hiding from the world when I battled bosses and gathered potions as I was augmenting it, reminding myself that even when things were frustrating or imperfect or didn't go as planned, there was a way to get to the other side (or at least a detour to distract me until I could make it there). I envied how Link could skip through time so effortlessly, could age or take off seven years from his life the way I changed dresses. I dreamed about the game, or some larger-than-life horrible glittering version of it, at least three times before deciding not to play before bed anymore.

I didn't plan to be poised to fight the final battle on that night before my birthday but I did love the symmetry of it, and the solitude. Two beers deep, cross-legged in my room, I confronted the sneering villain in his crumbling castle. I had my strategy all figured out. (During this period, my Chrome homescreen helpfully reminded me that I was visiting GameFAQs to consult walkthrough guides more frequently than I went to, like, Pinterest.)

And I know it sounds insane — it's a GAME, it's not REAL — but I was nervous. About what, I'm not quite sure. About having to start the final portion of the game over again if I lost, about running out of momentum, about facing off against this massive snarling thing I'd never confronted before without anyone sitting beside me. About — even in this imaginary space — failing.

It was a lengthy battle, marked by distinct phases and a terrifying, piercing soundtrack. (Even though I was alone in my apartment I still wore my headphones — it felt somehow more intimate, more manageable, that way.) I screwed up a few times, knocked to the ground by the rays of light Ganondorf hurls, and then all of a sudden I was confronting him in his final monstrous form and then the game was done. Link had his sword back and the land of Hyrule and the princess were safe. I was winded, and then I was sad.

The final credit sequence is essentially a lovely, massive party attended by all the until-now unconnected characters you've met over the course of the game, and even though it was charming, it was also a bitter reminder that I didn't get to participate anymore. When you finish a game you've loved, the first instant when you no longer have control over the character feels like a door slamming shut. I had to put both feet firmly back in my own life, where there were no dungeon maps or songs that sent me hurtling across the world. This confounding, strangely comforting puzzle that had lingered unfinished for so much of my life was all of a sudden done.

What I really missed, and continued to miss more for the next weeks as I returned to my usual subway pursuits, was the power the game lent me. You don't actually have control over the narrative in any real way — you can't say fuck it to the adventure and raise chickens with Malon the redheaded farm girl for the rest of Link's earthly days (omfg IF ONLY). But it is yours, and it does feel like you are making something, or at the very least a vital participant. For me, playing this kind of all-consuming game feels closer to the act of knitting than it does to reading. "I did that!" you whisper to yourself, even when there are bigger things going on or nobody else really cares. Except when you are done with a game, it hardens and retreats to someplace you can't quite reach anymore. Pride tinged with mourning is an odd combination, but one that feels unmistakably similar to growing up.

That night, I watched as the credits rolled and faded, first to black, and then back to the starting screen. I saw that my now-17-year-old brother, the first person I told when I beat the game, had written on my Facebook wall.

"Never change," he wrote, for my birthday and for my recent victory. "Though really this initiates you into full adulthood."

I snorted. Midnight quietly came and went and I was 24. Link, however, stayed firmly shut in the game, not exactly 10 and not exactly 17. His reward for leaving his home was that he, eventually, got to return to it, to go back to the childhood where he was safe and happy but never quite fit in, leaving a hole in the future he had fought so hard to protect. I didn't want that, I realized, not really. I wanted forward motion, not cycles; messiness and chance, not walkthrough guides. I closed my 3DS and put it on the shelf above my bed, leaving a younger part of me inside.