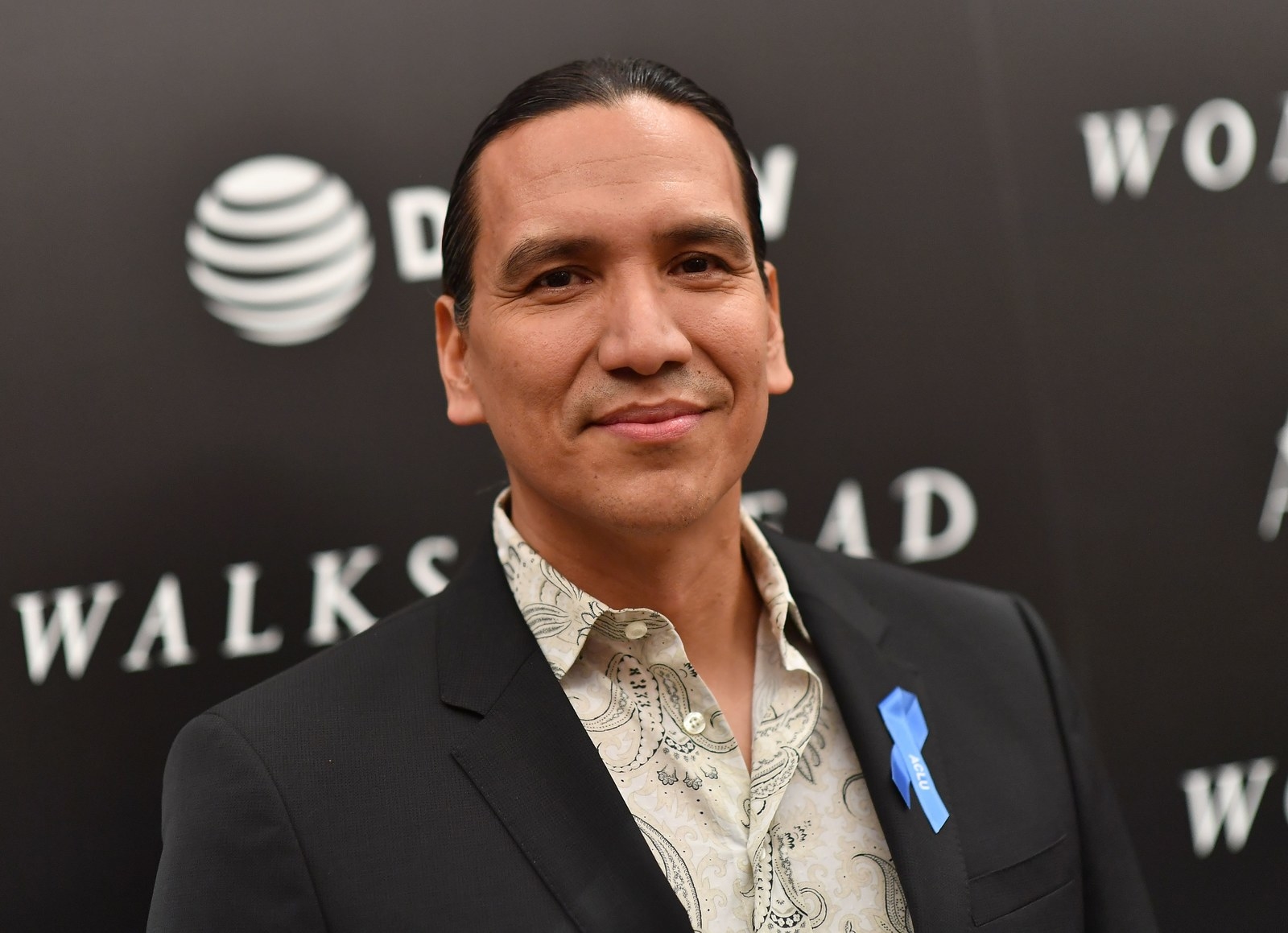

At its heart, Woman Walks Ahead is a film about fighting against erasure. A biographical film, director Susanna White characterizes it as an “anti-western” — a recalibration of a genre that has historically sidelined and maligned women and indigenous people while glorifying violence often committed by white men. Michael Greyeyes stars in the film as famed Hunkpapa Lakota leader Sitting Bull along with Jessica Chastain as Catherine Weldon, a white woman who painted his portrait and campaigned for Native rights by his side. Almost immediately after Chastain’s casting was announced in 2016, Woman Walks Ahead faced accusations of white saviorism. The film’s title centered Weldon, after all, sparking the impression that this would be yet another western focused on a white perspective, instead of one from an actual indigenous person.

For White, Greyeyes, and Chastain, the white savior narrative is one they saw as woefully inaccurate. “I felt it was unfair,” Greyeyes told BuzzFeed News. “It’s actually not true within the context of the film.” As Chastain told BuzzFeed News, she felt the criticisms came before the public had all the information. “We really need to look behind the scenes, and read the script first, or watch the film first,” she said. For the people making it, the film was about a noted leader at a crossroads and a white woman learning how to make herself useful as an ally. “In no way is she a white savior,” White said, noting that she considers Catherine to be more of an observer. “She’s anything but a white savior, really, because she’s powerless to stop the events.”

“It took a long time to get the movie made, because to finance a movie on a female lead with a Native American man starring opposite her was very, very hard.”

Woman Walks Ahead opens as Catherine leaves New York, naive but intent on painting a portrait of Sitting Bull and re-embracing the vocation her late husband had barred her from. She soon meets Sitting Bull, listens to his perspective, and as the two grow close she becomes politically involved in a campaign against a treaty that would steal more land and resources from indigenous people for the US government. Though the film eventually highlights more of Sitting Bull, the first act does establish that Catherine is the entry point into this story. Focused as it was on two characters marginalized in very different ways, the script sat unmade for 12 years after writer Steven Knight finished it. As White put it, “It took a long time to get the movie made, because to finance a movie on a female lead with a Native American man starring opposite her was very, very hard.”

For Chastain, the film was an opportunity to highlight the story of a woman who had been relegated to the footnotes of history; for Greyeyes it was a chance to play a historic Native character who was written thoughtfully. “From the moment I picked up this script, I realized I was dealing with something quite different,” Greyeyes said, adding, “it was a paradigm shift in the kind of writing that’s coming out of our industry.” He was used to scripts that use Native characters as foils “against larger questions that the so-called dominant majority want to answer,” and noted that “this film avoided that completely.” He responded in particular to Sitting Bull’s humor and the way the script stripped all glorification out of its violence. “When I saw Sitting Bull portrayed in a full humanity, in three dimensions, I knew I had to be part of the project,” he said.

“To concentrate on her ethnicity and her position ignores, again, erases indigenous contribution to the film, my contribution, the contribution of producers, advisers, of many crew members, the community itself.”

When it comes to the discussions around Woman Walks Ahead’s white woman co-lead, one of Greyeyes’ frustrations is that he sees the conversation as further sidelining the Native voices that actually did take part in the film on and offscreen. “Chaska, [Sitting Bull]’s nephew, he’s a continual advocate for Sitting Bull to do more,” he said, referring to the character played by Chaske Spencer, who pushes Sitting Bull into action more than Catherine does. “To then place Catherine as the advocate erases Chaska entirely.” Greyeyes warns against continuing to focus mainly on white involvement, even the director’s. “You can look at the director, Susanna, who is an authorial figure within the context of the production,” he said. “But to concentrate on her ethnicity and her position ignores, again, erases indigenous contribution to the film, my contribution, the contribution of producers, advisers, of many crew members, the community itself. I actually view that argument as not only inaccurate, but simply lazy.”

It was important to White, Greyeyes, and Chastain that the voices and talents of Native people be included throughout the production process. “My background’s in documentary, that’s how I started out,” White said, “so it’s kind of first principles to me that if you’re making a film about a community you engage with that community.” She hired Willi White, a young filmmaker from Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, to be her assistant, mentoring and taking advice from him throughout production. White also talked to elders and the tribal council on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota, obtaining their consent to make the film, and was adamant about including the Lakota language.

When boarding the film, Chastain also made it clear to White that she required all of the indigenous characters in the film be played by actual indigenous actors. One day on set, Chastain looked over in the makeup trailer and saw a number of seemingly white day players being put into wigs. Upon inquiring about it, she learned they’d been hired without White’s permission for a bareback horse-riding stunt. Once White was informed, she cut the scene. “She wanted to make sure that every single person in the film was true to what they were playing,” Chastain said. “I don’t think that happens very often.” White confirms Chastain’s account: “As soon as I found that out I thought, there is no way we’re going to have that in the movie.”

White emphasizes the importance of shadowing, mentoring, and providing jobs in the effort to raise up more Native voices in Hollywood. “I think the best thing one can do is empower people, and I hope that Willi will go on to make successful films of his own as well and tell the stories of his community,” she said. “I think [it’s about] increasing visibility, representing Sitting Bull as the sophisticated, intelligent, extraordinary man that he was, and putting that side of the story out there.”

Only 0.23% of speaking or named characters on film between 2007 and 2016 were Native American or Alaska Natives.

Chastain is also looking to increase visibility through the process of promoting the film: She said she’s been butting heads with media outlets as she tries to get Greyeyes in the spotlight alongside her. “Even when doing press, it was really important to me that Michael Greyeyes is with me,” she said. “And I might be in trouble for saying this, but there’ve been situations where I’ve had to fight to have him be part of the conversation.” According to Chastain, it’s an ongoing struggle — many outlets lean on the visibility of already-famous movie stars. There aren’t many — or arguably any — Native actors who are household names outlets feel they can bank on for SEO. According to research from the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative provided to BuzzFeed News, only 0.23% of speaking or named characters on film between 2007 and 2016 were Native American or Alaska Natives.

“It goes beyond just making the films, it goes beyond who financers see as valuable to a story. It goes to media. Who does the media see as valuable?” Chastain said. It opens up a lot of questions when it comes to white allyship. “The question I think we all should have is, like Catherine Weldon, how can I be of service to move everything forward? And we need to look at whatever [we can do]. How are we working to amplify the underrepresented groups?”

For some though, the film’s title and the way it leans on Catherine might remain a deal-breaker despite the filmmaker’s best intentions. As Paula Young Lee wrote in a Salon piece about the film in 2016, “the setup would be a lot more interesting if the film unfolded from the perspective of a young Lakota girl born and raised in the Standing Rock reservation, with a storyline exploring her bafflement and anger at this random white lady who shows up to play interlocutor and scribe.” Some people are just too tired — from the whitewashing history of Hollywood and media, but also from the very history of violent erasure Woman Walks Ahead presents — to engage with a movie that uses a white lady as its eyes and ears. As White herself said of that history, “It was an apartheid that went on, and I think that’s one of the things I’m proud that the movie shows.”

Greyeyes, for his part, has no problem with the film’s title centering Catherine. “I recognize how Hollywood works, I recognize [the importance of] names, posters, that kind of framing,” he said. “But with this production, and with these artists and collaborators, I never felt that I had to fight for something, I never had to fight for voice.”