One of the first things I was taught about being Japanese was that we all become ghosts. When my grandmother died, my mother told me we had to chant at temple every seven days after her death for seven weeks. We do this, she explained, so that my grandmother’s spirit won’t get caught in transition during the 49-day journey to enlightenment. I was 12 years old. I didn’t want to know what would happen if we didn’t chant hard enough.

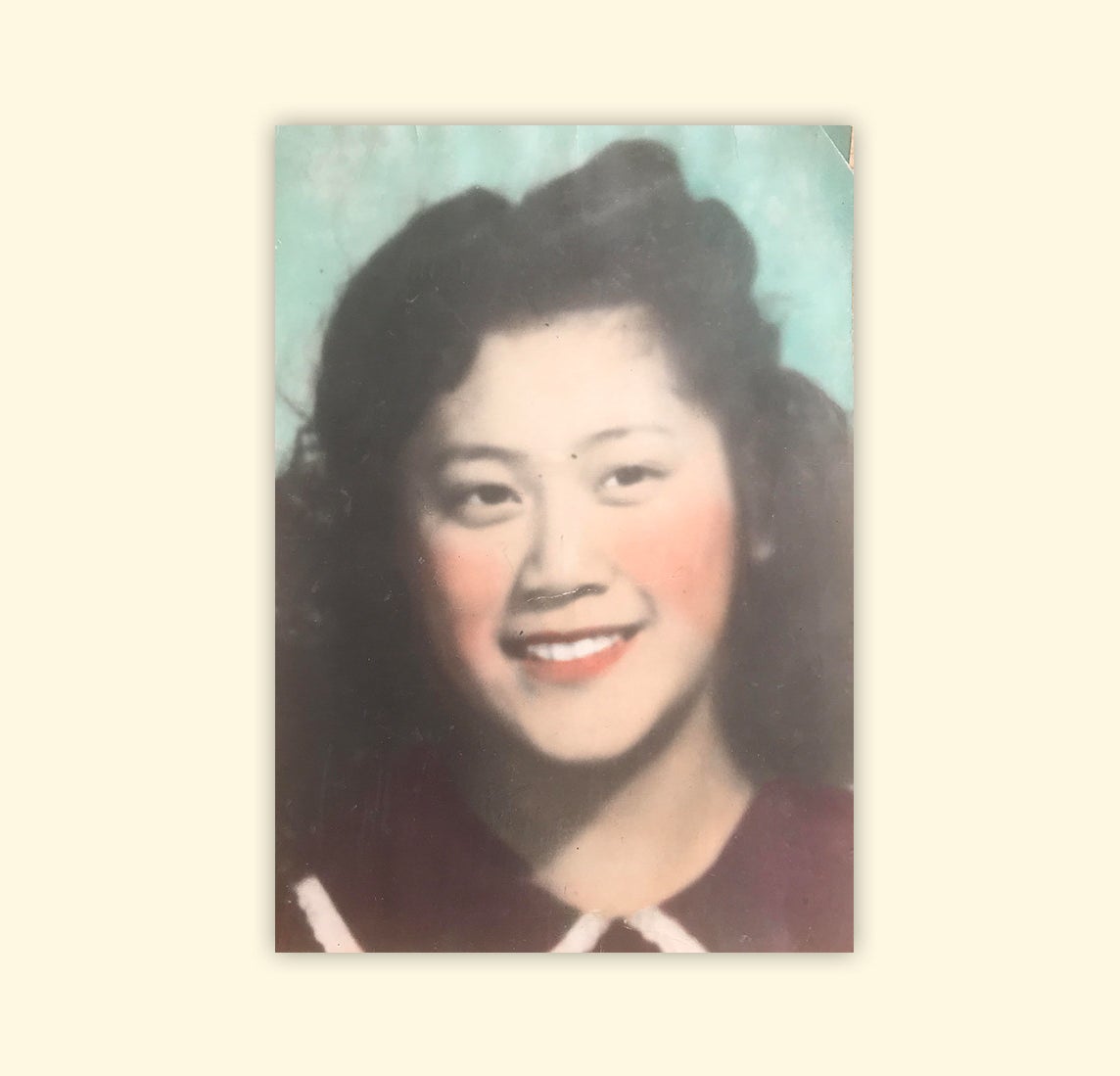

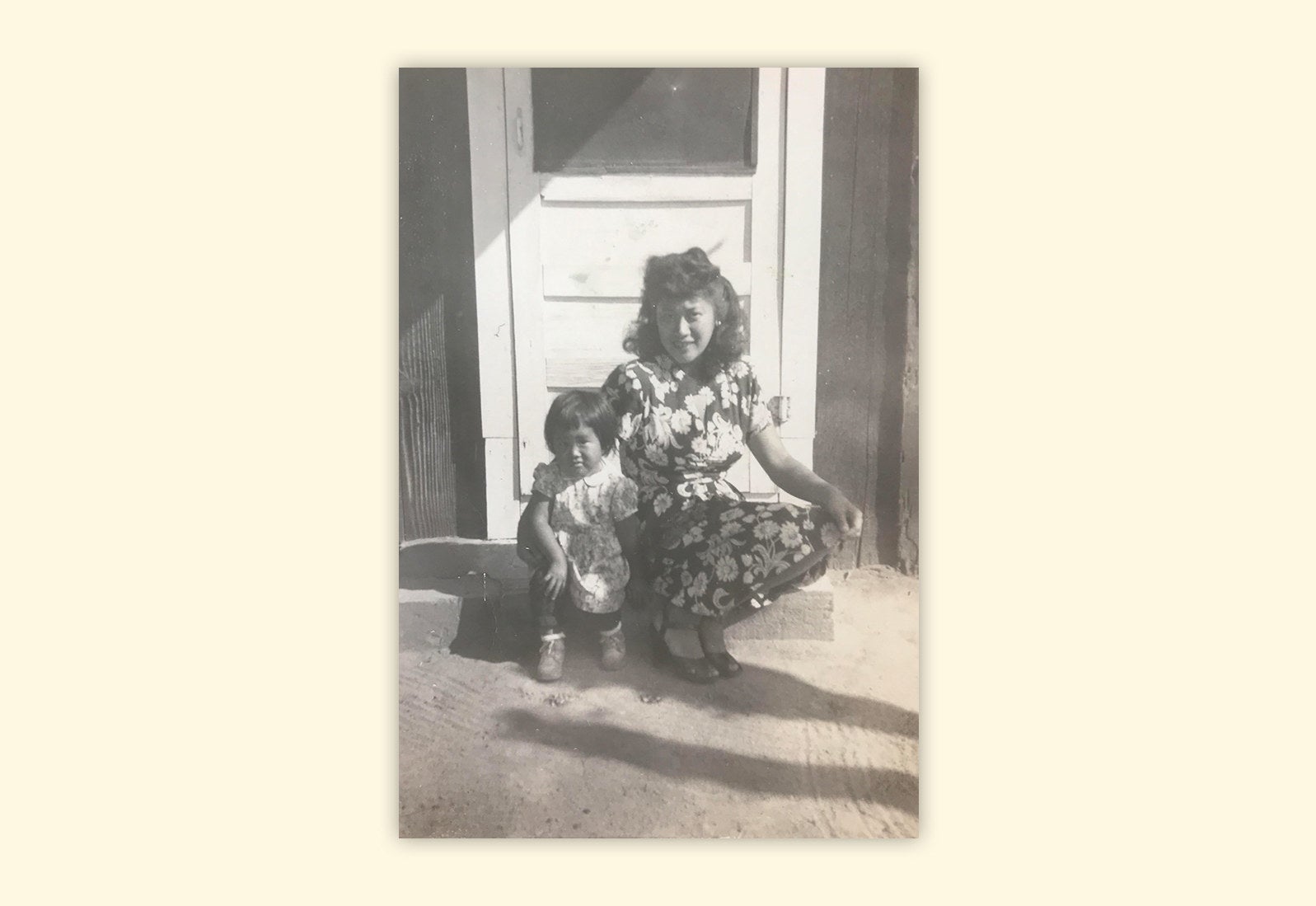

Once, my grandmother was a 15-year-old girl born in the United States, forced from her home in Oakland into a detention camp in Utah, simply because she was of Japanese descent. I imagine her lying on a cot in the unbearable desert heat where her country has incarcerated her, wondering where her life had slipped away to. A specter of a girl chasing after a specter of a life. What I didn’t understand when I was young was that she’d already been a ghost.

I thought about my grandmother and her ghost while I watched the first episode of the second season of The Terror, which premiered Aug. 12. Subtitled Infamy, it’s the second installment of AMC’s anthology series, which retells historical events through a supernatural lens. The excellent first season, which had a small but mighty following, told the story of the doomed 1845 Franklin expedition to the Arctic. By using metaphysical elements like magic, myth, and monsters, the show imagines that what killed the men on those ships was more than starvation, more than loneliness or even hubris.

This season of The Terror, helmed by Max Borenstein and Alexander Woo, bears no resemblance to the content of the first, except that it also concerns a group of doomed people and uses speculative fiction tropes to tell a story of a real-life psychological horror. Here we follow the Nakayama family, part of a Japanese American community in Southern California who are all shipped off to a fictional internment camp in Oregon. Along for the ride is a mysterious and violent spirit tormenting them, alluded to as a bakemono monster.

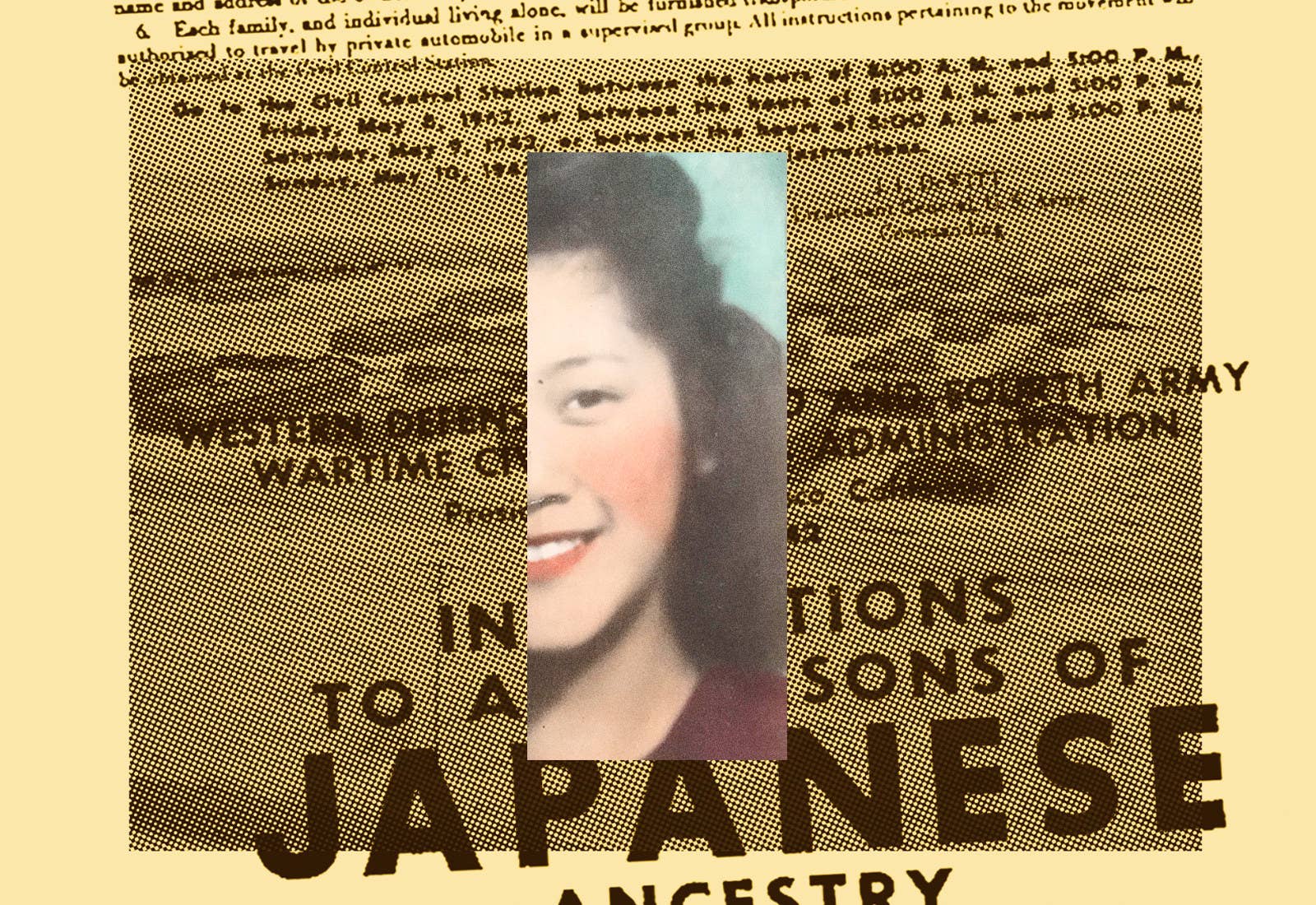

I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t familiar with the event of Japanese American incarceration, even as a young child. Our home was filled with totems, like my great-grandfather’s watercolors from inside the camp, and a butsudan shrine to the generation who lived through it. Most vividly I remember a framed poster of Executive Order 9066, which Franklin Roosevelt used to authorize the incarceration of all Japanese Americans along the West Coast. But I don’t remember a time where I saw that history represented in media. I don’t remember talking about it in high school history classes. I’ve seen countless mainstream World War II films, but only one (Snow Falling on Cedars) that touched on Japanese American incarceration. I’d never seen a television show about it. Until now.

In The Terror, finally and unapologetically, we see that experience represented. We see Japanese Americans in 1941, going about their lives, speaking English and Japanese, doing things my family also did: working, fishing, praying, mourning. The prewar lives of Japanese Americans are an essential part of California history, American history, and World War II history, and yet their existence has been largely erased or glossed over in popular culture, reduced to imagery of geisha and kamikaze fighters. In the first two episodes of The Terror, I saw people who looked and dressed like the pictures of my grandparents taken before the camps, which is to say they looked and dressed like average Americans in the midcentury, except they were Japanese. I drank this depiction up as if I’d been thirsting for it my whole life. This is the before. This is what was stolen.

The prewar lives of Japanese Americans are an essential part of California history, American history, and World War II history, and yet their existence has been largely erased or glossed over in popular culture.

But the horror element, not the history, is the show’s main calling card and what places it in The Terror’s anthology world. Without it, the season plays as a straight family drama, centering on competing generational values, the Old World versus the New World, simmering under the pressure of an intensifying war. But with the genre element — the malevolent spirit taking the form of a mysterious woman, who is both seen and unseen, who seems to be able to control bodies, making them wreak violent havoc — the show demands that you consider all acts of atrocity as horror. The first episode opens with the disturbing suicide of Mrs. Furuya, who we later learn was in an abusive marriage with a husband who frequently and brutally beat her. Later in the episode, as her suicide ripples through the community, two younger characters, Chester Nakayama (Derek Mio) and Amy Yoshida (Miki Ishikawa), try and fail to understand it. For Amy, secretly in love with a white naval officer, and Chester, carrying on a secret affair with a Mexican American woman named Luz, it seems to be the tip of what they don’t understand about the generation above them. Eventually Amy says to Chester, “You know what’s truly scary?” and goes on to describe Mrs. Furuya’s relentless abuse at the hands of her rageful husband. “That’s a monster,” she says — humanity, and its frequent desertion.

In the show, Chester (played tenderly by Mio, of the yonsei fourth generation, like me) is a good son and an avid photographer. Lately, though, his photographs seem to show smears and blurs where there should be faces, possibly the effect of the ghost that lives among them, erasing her presence. I thought immediately of Dave Tatsuno, the real-life entrepreneur incarcerated at Topaz in 1942, who convinced the guards to let him smuggle in a camera so he could take photographs and videos.

When you visit the Topaz Museum in Delta, Utah, shots from Tatsuno’s film are the first thing you’re shown. Silent moving images of Japanese American men and women eating, holding babies, reading the Topaz Times, playing in winter snow, fanning themselves against the summer heat. The simplicity and plainness of that footage caused a lump to form in my throat right away. I sat in the quiet screening room with only one other family sitting behind me, with two fidgety children. They seemed to have spontaneously wandered into the museum on their way to somewhere else, the opposite of a pilgrimage. As I watched the film, I became acutely aware of my direct link to these images, scanning the normalcy for glimpses of my own relatives and fighting back hot tears. Behind me, the children said they were bored.

Cameras weren’t allowed in the camps, read the text on the screen that flickered light across our faces in the dark. And yet this film exists. The effect of watching it is something like resurrecting a spirit. Speak, I wanted to say. Scream. As in Chester’s blurry photographs in The Terror, the camera ban took away the prisoners’ ability to see, to document, to say this happened. The erasure almost worked.

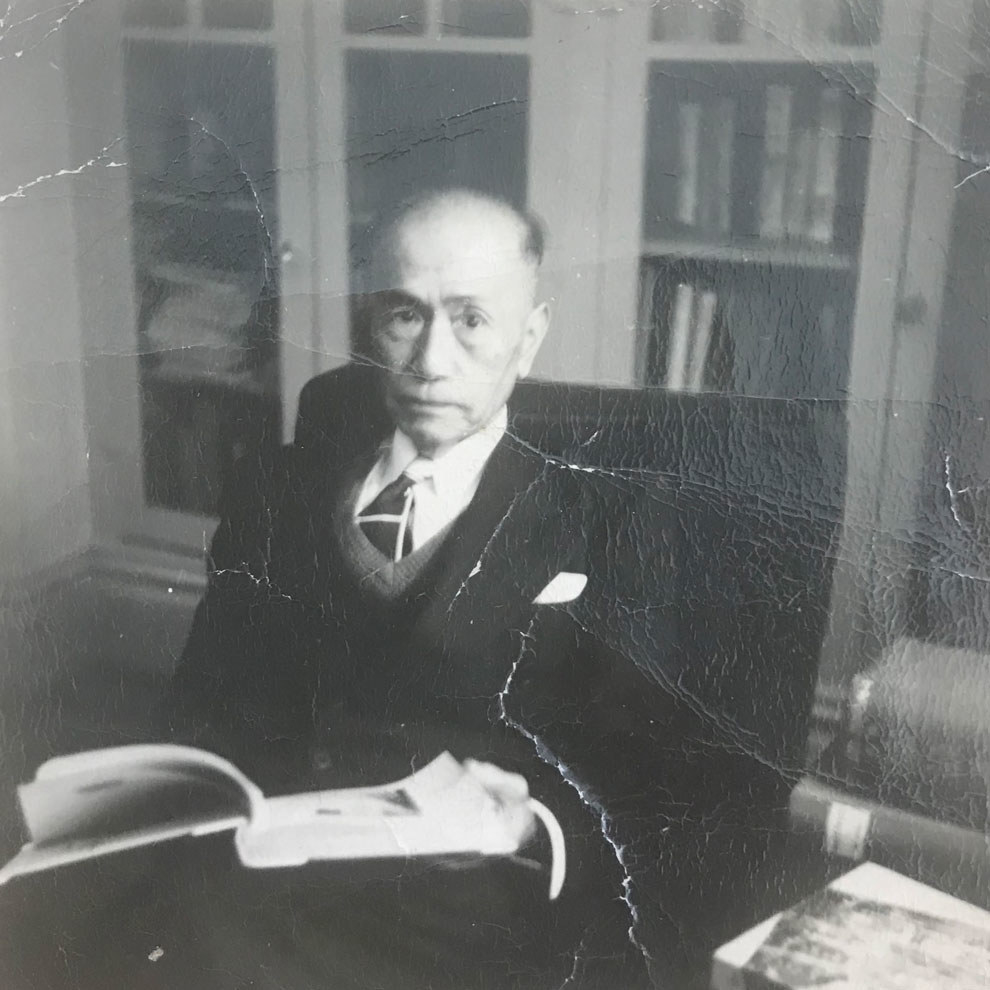

My grandmother’s name was Takeko. She was American-born, and the third child of Chikaji Kawakami, an artist from Kagoshima, who had lived legally in the United States for 41 years before being taken to the camps. Though Chikaji trained in painting in Japan, he settled in Oakland, where he fixed motorcycles and owned a laundry business. After bearing eight children, his wife died, and then the family was rounded up by decree of Executive Order 9066, passed down in February 1942. In late April, because the camps weren’t ready, they were among the 7,000 Japanese Americans from the Bay Area who were imprisoned in hastily set up barracks at the Tanforan Racetrack, near the San Francisco airport. (Japanese Americans from other regions were held in other similarly uncivilized conditions.)

A portion of these racetrack barracks were converted horse stalls, their corners still caked with dried manure. There were 24 latrines on-site for those 7,000 people. They were engineers and doctors and musicians and teachers. Most of them, including my great-grandfather, lost the homes they owned and any possessions they couldn’t carry with them. Babies were born at Tanforan, without cribs or medicine, among horseflies and fleas. Despite the general barbaric nature of the entire event, it’s the lack of privacy that may have been particularly torturous for the modest issei generation. My mother still reminds me of this — how women like her grandmother, who thought showing the nape of her neck in a kimono was scandalous, must have reacted to suddenly living in horse stalls. It’s hard to know what the real horror was, when there were so many to choose from.

Babies were born at Tanforan, without cribs or medicine, among horseflies and fleas.

Chikaji, Takeko, and the rest of the family lived at the Tanforan Racetrack for four months while Topaz was being built in remote Utah. In fact, 200 nisei left Tanforan, their current prison, to help build Topaz, their future prison. Inside the racetrack, Chiura Obata, a well-known artist and art professor at the University of California, Berkeley, founded the Tanforan Art School. In four months, in a converted mess hall, a group of classically trained artists from Japan taught 95 art classes. Chikaji made art on the periphery of this school. Tanforan also published an official newsletter, had an education center, and offered “Americanization classes,” all begun and run by prisoners. In the absence of humanity, humanity rushed in.

In September 1942, all the prisoners were officially moved to Topaz. You can’t visit Tanforan these days because it’s a shopping mall. The racetrack was torn down in the ’60s. But you can visit Topaz, where at least the shards of the structures remain, and you can visit the excellent Topaz Museum in Delta, run by a volunteer and local, Jane Beckwith. Beckwith is a Delta native and previously taught high school. She remembers teaching a history class with a German exchange student in it. As she talked about the incarceration and Delta’s proximity to one of the camps, the German girl began to cry. “The world knows about German camps,” she said. “But no one knows about this.”

When I visited last summer, the first thing Beckwith did was apologize to me.

“This museum represents the nisei perspective,” she said. “And I know that’s now controversial.”

What she meant was that the nisei generation, my grandmother’s generation, tended toward assimilation after the camps. They used federally encouraged euphemisms, like “relocation” and “internment,” instead of “incarceration” and “imprisonment,” as though what happened was a reasonable movement of people from one location to another. What Beckwith meant was that the museum isn’t as incendiary as it should be.

She shouldn’t have apologized. I spent hours walking through the exhibits, which describe life inside Topaz with tender but exacting detail. There are exquisite minuscule dolls that prisoners crafted from tiny desert shells. There are photographs of weddings where brides carried flowers made from crepe paper and ribbon scraps. There are yearbooks from the school inside the camp, in which I found a photo of my great-aunt, Umeko, with a description saying she “liked cooking and hopes to become a housewife.” It is this, the mere record of the lives lived inside Topaz, that is so powerful. People frozen in photographs and remembrances, caught in the years when their government tried to evaporate them.

The exhibit I was most enamored with was a diary from a third-grade classroom. Every morning of class, the teacher, Anne Yamauchi, talked with her students and wrote down a summary of the discussion. In perfect handwriting, she recalls events of Topaz that feel at once mundane and tragic, the observations of imprisoned third-graders who have no understanding of their role in the long history of American racism. Sentences like “Last Saturday, a dog had a fight with a porcupine” live next to sentences like “Many people left Topaz this afternoon for the ‘Tent City’ in Provo, Utah.”

In one entry, a single sentence stands on its own: “We have a new American flag for the classroom.” In other entries, the patriotism left me breathless. “Please remember to put 10% of your pay into war bonds and stamps,” the class writes. And then, inexplicably, “We should not kill spiders because Uncle Sam needs them for the war.” The children’s careful pencil drawings accent the diary’s sillier moments. One from July 30, 1943, describes how “Edwin went swimming at the pig farm and saw a baby shark.” Overlaid on the words is a drawing of a gray shark hovering just under the surface of blue water, waiting, teeth bared. The entries abruptly end when Anne Yamauchi’s family is transferred from Topaz to the Tule Lake Segregation Center in California, where those perceived to be “disloyal Japanese” were held in isolation.

I want to know about the ghosts. What happened to those third-graders at Topaz? What happened to the teacher’s family? As clearly as their voices are heard in the museum, their fate feels opaque, shrouded. The blank spaces of untold stories and silent suffering throb throughout the museum, and perhaps that’s what Beckwith was also apologizing for. The impossibility of telling every story, the whole story. The way a museum shudders under the weight of what has been, for so long, unspeakable.

I visited last summer, but the memory of that third-grade diary hurtled me back to the first time I saw images of the hordes of children the US government is keeping in detention centers near the Mexican border, away from their parents. I thought of the Topaz children and their quiet endurance when I read about the immigrant children in Texas and their lack of access to toilets and soap and medical care and food and the outdoors and their families. I thought of the diary when I heard 11-year-old Magdalena in Mississippi, weeping and pleading on television after her father was picked up in an ICE raid at his work. What have we done to her future? Will she become a ghost of herself?

We haven’t really talked about the horror of Japanese American incarceration, not in the mainstream, and now we are repeating history. Worse, and in plain sight. A horror show on our nightly news. We should talk about it now. We should be fully and completely afraid. Maybe the horror in The Terror is the kind to actually reach us.

On the drive from Delta out to the site of the Topaz ruins, the sunbaked landscape begins to look like a 1970s slasher film. First there are some low shacks. Then there are fewer. Then there are none. Then, as Beckwith makes a turn into the 19,000-acre site, there is so much nothing that it is something. From the truck, she points to empty spaces and describes their former landmarks in present tense. There’s the baseball field, the Buddhist church, the library, the dry goods store. She says she was told a tofu factory also existed, but she can’t find records of it. She points to the spot where it used to be anyway.

I am mostly silent in that truck. I am shocked by my recognition. My great-grandfather Chikaji left us with many of his watercolors from that time, which I grew up staring at. They are not pretty — all dehydrated beige and army brown and clouded with dusty light — but now I realize it’s because this landscape is not pretty. This is unlivable desert, and not the Instagrammable kind. We get out of the truck to walk around, and my legs are immediately scratched up by greasewood and scrub, growing out of splits in the long dead ground. Watch for scorpions, Beckwith warns me. And fire ants. And nails. She tells me the site was quickly demolished after the camps were closed in 1945, and they did a poor job. Foundational bones of structures are still scattered around. Broken roofing and shards of ceramic cups and burned hair combs are everywhere.

She led me to the exact spot where the barracks on Block 12 once stood, where all seven of my grandmother’s family members lived in two rooms. I balanced on splintered wood bolted to the ground. The land is barren, so dry and cracked from the heat, it bounces underfoot. Impossible land to farm, which, of course, was what the camp administrators had them do. These former city-dwelling small business owners now growing crops in godforsaken country.

This is a site of destruction. Of buildings and fine china, yes, but also of possible lives. I haven’t told you the story of the world-class cross-country runner who regularly escaped the barbed wire fences to try to keep up his training. Or the former Disney animator who drew a patriotic cartoon for the Topaz Times called “Jankee,” short for “Japanese American Yankee.” But there was destruction of actual lives, too. On April 11, 1943, 63-year-old chef James Wakasa was shot to death by a guard while chasing a newspaper caught in the wind. The guard was found not guilty, and military officials referred to the incident as a “justifiable military action.”

What about the baby who contracted an illness from filthy conditions at the racetrack and died after he was released from Topaz, as a teenager? Or the 7 p.m. curfew that kept the prisoners from tending to their food crops during flash floods? To walk in Topaz is to walk among lives stamped out, and the place where they birthed new versions of themselves. To speak about the people there is to speak across different worlds: the was, the would have been, the almost was, the is. Which world am I in?

Beckwith offered to take my picture standing at the ruins of their barracks. She thought I would want a photo because I was a descendant of this. And it occurred to me that I kept referring to the family here as her family. But this happened to my family. As she snapped away, I was unsure what kind of face I was supposed to make in the photo. I wasn’t happy, though I was glad to have finally made the pilgrimage. I wasn’t devastated, though I was deeply sad, in a heavy, subterranean kind of way. I felt stretched between worlds, my presence attempting to bridge the tragedy of the past to the invisible trauma of today. I had no language for that in-between-ness. I’d never posed for a picture from a disappeared space. Now I was haunted too.

When my grandmother was released from Topaz, she was only allowed to go east, to Illinois, where a family friend agreed to sponsor her. She was 17 and got a job as a maid. She didn’t finish high school. She didn’t go to college. She shed Takeko and became Joan. She met my grandfather, a Japanese American who had enlisted in the Army to avoid going into the camps. When they were allowed to, they moved back to California, where he became a farmer, and she a farmer’s wife. They had my mother. They had a son. Though her father remained angry about the incarceration until his death, Joan and her family spoke mostly English to their children and felt patriotic. The son grew up and then there was another war, in Vietnam, and he joined up and saved enough soldiers’ lives that he was awarded a Silver Star and a Distinguished Service Cross.

That The Terror has invented a monster to tell the story of Japanese American incarceration makes sense to me. When a past has been erased or glossed over, trying to commune with it can feel supernatural. When the past is horrific, the communion can be violent. Toward the end of the first episode, the mysterious ghost woman gives Chester a tea leaf reading.

“They say you are two people,” she tells him. “Light and darkness. Life and death. You live in two worlds but are home in neither.” Splintering is Chester’s fate, the ghost seems to be saying. And how many times, I wondered. My grandmother, at 15 years old, losing herself, replaced by Joan, who knows now that she is feared and unwanted.

In 1988, Joan was awarded $20,000 from the federal government as apology for locking her up when she was 15. Now widowed with grown children, she spent that money on a few nice things for herself: some dresses, a perm, some costume jewelry. She took glamour shots that she gave everyone copies of. Seven years later, she died of a brain aneurysm. As a child, I pictured her wandering through the painful afterlife, looking for a gate to the next realm, wearing a feather boa and blue eyeshadow.

We should be fully and completely afraid. Maybe the horror in The Terror is the kind to actually reach us.

Does every story about Japanese American incarceration have to be a ghost story? Of course not. But is every single one of them a story of a life lost? Yes. By telling the stories, perhaps we can undo some of the loss. Maybe one day everyone will be able to see the horror in the plainness of images like Dave Tatsuno’s, and maybe we will see it in mainstream television and film. But for now, I’m interested to find out how the horror convention compounds the horror of actual life on The Terror. The pilot episode was unsettling. And we should all be profoundly unsettled.

I haven’t stopped being unsettled since my visit to Topaz. The whole place has a surreal quality to it. In the truck on the way back to Delta, while we’re talking about all these stories and how to tell them, Jane Beckwith points toward the horizon to a lot and tells me there are cosmic ray detectors out there. A collection of telescopic machinery measures super-high-energy particles that travel from distant sources in the universe to collide with charged particles in the Earth’s atmosphere. It sounds to me like the stuff of science fiction. And most of the scientific organizations involved in the project are from Japan, which means Japanese physicists regularly visit Delta. Talk about collision, I think. I wonder if my grandmother could ever have imagined it, Takeko out in the desert, or if by that time she’d stopped imagining. Beckwith says she sees the Japanese physicists pass by from her museum. They are setting out to document messages from far-flung galaxies, to study what invisible force powers something so far away.

Before she drops me off, we sit in the car and talk more about disappeared lives, and how to track them. She wants to make sure I know she isn’t trying to speak for Japanese Americans with her museum. She wants me to tell the story. Stories power the world, she says. I’m looking out the window when she tells me this, looking for cosmic rays, trying to catch some of that invisible light. ●

Aja Gabel's debut novel, The Ensemble, is out now from Riverhead Books. Her essays have appeared in the Cut, Catapult, the Kenyon Review, and elsewhere. She holds a BA from Wesleyan University, an MFA from the University of Virginia, and a PhD from the University of Houston. She lives and writes in Los Angeles.